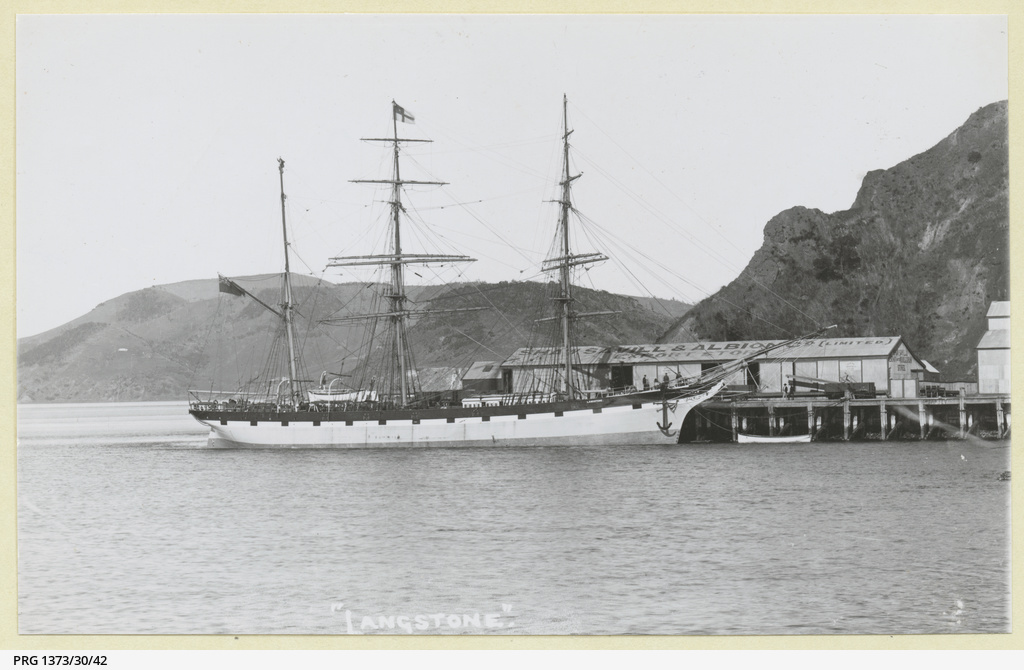

Shipwreck

Langstone departed Bunbury at 6.30 a.m. on Saturday, 8 February 1902. The morning was fine with a breeze from the south-south-east. However, at noon it commenced blowing a gale from south-south-west to south-west with a heavy cross sea running. The first mate, Carl Sunbye, later told a reporter: ‘When off Cape Naturaliste some 15 miles the captain gave instructions to lie out to windward—that is westerly—so to be well clear of the reefs’ (West Australian, 12 February 1902, 7f).

According to evidence given by the mate, the barque was sailing at eight knots on a course of N.W.½W. Captain Mørch had been watching out for the Naturaliste Reef, which he anticipated should be awash, but:

“…with the heavy breaking of the seas all round made it impossible for me to detect the break on the reef. About 2 o’clock in the afternoon I suddenly picked up the reef right in front, and at once attempted to luff, but it was too late, and the next moment we went crashing over the rocks, which I am satisfied formed a portion of the Naturaliste Reef, the Cape bearing S.S.W. about 24 miles. The ship at once commenced to go down, and when, on sounding the hold, I found that she had made nine feet of water in a few minutes, I gave the order to clear away the boats” (statement by Captain Mørch quoted in Bunbury Herald, 13 February 1902: 2e).

In fact, according to the first mate, Langstone struck three times. It then listed over with seas breaking over the bulwarks and slipped off the rocks. Captain Mørch said that this saved them, for they could not have manned a boat while on the reef, it being too rough.

Three boats were lowered, but one immediately filled with water and because of the rough seas it could not be bailed out. The second mate, Johann Weiseth, and seven of the crew got into the lifeboat, and the captain, first mate, steward, carpenter and a seaman went in a smaller boat—referred to in a newspaper report as a praam. This would have been a small lightly built dinghy normally used only in harbour.

Langstone lay for a minute or so with the keel vertical, bow down, and only the poop, mizen mast, and part of the keel visible, before slipping beneath the waves into deep water. From the time it struck to the time the boats were lowered was ten minutes, and it sank only ten minutes after that in 23 fathoms (42 metres) of water.

Survivors

The southerly direction of the gale-force wind and the consequent beam seas forced the lifeboats away from a course for Bunbury, obliging them to run more northerly. The wind was too strong for any sail to be set, and the crew used the oars to keep the boats heading before the seas. The lifeboat took the smaller praam in tow, and, running before the strong wind, both craft had great difficulty in staying afloat, the crews having to constantly bail.

That night, one of the seamen, Andreas Larsen, dropped his oar and fell exhausted into the bottom of the lifeboat. He was raving incoherently and tore off some of his clothing. The captain delegated one of the crew to try to keep Larsen’s head above the water swilling around in the bottom of the boat. Larsen, aged 22, had been shipwrecked only a short while previously, and had been picked up by Langstone at Trama Tave in Madagascar just before it departed for Bunbury. On Sunday morning, those in the praam transferred to the far more seaworthy lifeboat, and the small dinghy was let go about 16 miles (30 kilometres) from land. The planks of the lifeboat had dried and shrunk during the vessel’s stay in Bunbury, and it therefore leaked very badly. This gives an indication of the danger which had been faced by the men in the even more unseaworthy praam.

With two men bailing continuously they managed to set a small sail about noon, and sighted land about 4.00 p.m. that afternoon. The boat reached the shore some 30 miles north of Bunbury near Lake Preston at around 5.00 p.m. About a kilometre from the beach, the survivors found the home of Mr and Mrs Salter. This couple took them in and gave them shelter for the night. The following day, Monday 10 February, the captain and some of the crew were taken to Bunbury by another settler, Arthur Jones, in his buggy. Here they reported the wreck to the Resident Magistrate, W.H. Timperley, at 10.00 p.m. that night. The reminder of the crew arrived in Bunbury around midnight.

There are some discrepancies regarding exactly when Larsen died and what happened to his body after the survivors reached shore. The captain said that on Sunday ‘at 3 p.m. Larsen, who had not recovered his reason, expired’ (Bunbury Herald, 13 February 1902: 2e). However, according to the mate, when they reached the shore at 5.00 p.m. Larsen was still alive, but only just, and had died that night on the beach. Both agree that Larsen was wrapped in a sail while he lay on the beach. Captain Mørch then claimed that when he was taken to Bunbury by Jones, he took with him Larsen’s body, handing it over to the police on Monday night. It was then placed in the morgue. This was hotly disputed by the local press:

“The captain’s statement in regard to bringing the body of the unfortunate man Larsen into Bunbury is flagrantly inaccurate. The man’s body was left on the beach for a considerable time, as a matter of fact until it was removed on Tuesday morning. The body only reached Bunbury on Tuesday at midnight, and when it was taken to the morgue it was in a very advanced state of decomposition. Larsen’s body lay on the beach at Lake Preston from Sunday afternoon until Tuesday morning, when it was removed and brought into town by P.C. Nesbit and Mr. Jones, a settler at Lake Preston, arriving at the morgue about midnight Tuesday (Bunbury Herald, 13 February 1902: 2e).

Doctor Williams examined Larsen’s body and concluded that he had drowned. This presumably had occurred while Larsen lay in the water in the bottom of the lifeboat. The inquest held on 12 February at the Bunbury Courthouse by the Resident Magistrate, with a jury consisting of J.G. Baldock, Harry Brashaw and Arthur Charles Cook came to a similar conclusion, their verdict being that the ‘deceased came to his death by drowning while in the state of unconsciousness and that no blame could be attached to any person” (Bunbury Herald, 13 February 1902: 2e-g).

As Langstone was a foreign owned vessel there was no official investigation into the wrecking, but a consular inquiry was to be held. (Worsley, 2012).

Factors contributing to the wreck

Gale-force winds and low-lying reef

The change in wind direction to a gale, combined with choppy, breaking seas, made it near impossible for the crew to detect the breaking waves on the low-lying Naturaliste Reef. By the time the lookout spotted the reef, it was too late.

Search for Langstone

Between the 9 and 13 of November 2024, Western Australian Museum Maritime Heritage staff participated in the search for the 19th century three-masted, iron-hulled barque Langstone as part of the Disney+ six-part documentary series Shipwrecks Hunters Australia Season 2.

The project was undertaken in collaboration with Terra Australis Productions and VAM Media, aboard the 14.5 metre power-monohull vessel, Ecuador, out of Port Geographe Marina.

The search involved a four-day survey the seafloor around Naturaliste Reefs using an EdgeTech 4125 tri-beam side scan sonar with a Geometrics G-882 Magnetometer piggy-backed to the side scan sonar. A 3 km x 5.4 km area, totalling nearly 230 km2, of seafloor was surveyed.

Discovery

On 12 November 2024, as part of the survey being carried out by a team of filmmakers and archaeologists from Shipwreck Hunters Australia and the Western Australian Museum, a side-scan sonar survey identified a wreck of an iron three-masted sailing ship.

A BlueROV was deployed to visually confirm the site, followed by a diving inspection carried out by two divers using closed-circuit rebreathers. The visuals received from these two inspections confirmed the wreck to be Langstone, discovered in 45-metre-deep water.

Protection

Langstone, being over 75 years old, is automatically protected under the Commonwealth Underwater Cultural Heritage Act 2018.

To learn more about the history and discovery of Langstone, watch the Shipwreck Hunters Australia Season 2 episode on Disney+, and read the WA Museum’s archaeological report.

Link to report: Historical background, search, discovery and inspection of the iron barque Langstone (1869-1902), Naturaliste Reef, Western Australia

Link to further information

Historical background, search, discovery and inspection of the iron barque Langstone (1869-1902), Naturaliste Reef, Western Australia.