The Western Australian Museum is part of an international team of 29 leading shark palaeontologists and neontologists who, last year, published research that challenged recent interpretation of the body shape of the megatooth shark Otodus megalodon.

The Museum’s Head of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Dr Mikael Siversson, one of the lead authors, said the ongoing research has led to a new paper published today that sheds new light on the size, body shape, and growth patterns of this ancient predator that lived 16-3.5 million years ago.

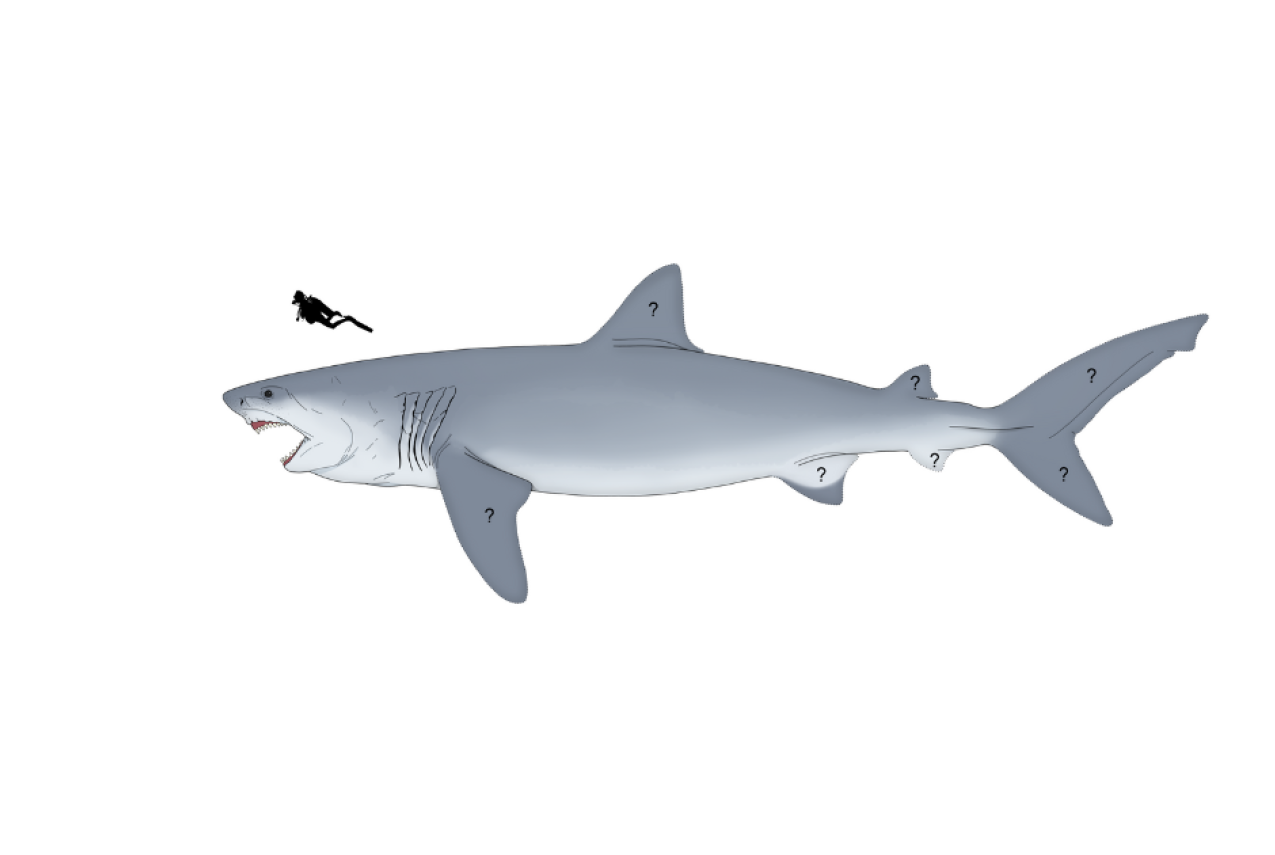

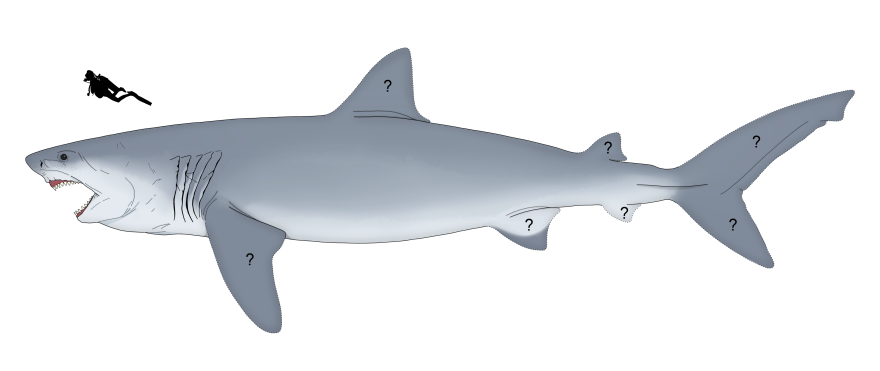

“The study, which involved analysing vertebrae from fossil specimens in Belgium and Denmark, challenges previous size estimates and presents the possibility that megalodon may have grown to a staggering 24 metres in length (some 4-9 metres longer than previously believed) and weighed an estimated 94 tonnes,” Dr Siversson said.

The research, conducted over the course of 2024 and 2025, used an innovative approach to estimate megalodon’s size by examining a tail-less vertebral column found in Belgium, measuring eleven meters in length, and comparing it to vertebrae from a larger individual found in Denmark.

“By analysing the relative lengths of the head and tail in over 145 modern and 20 extinct species of sharks, our team estimated the original body length of the Belgian specimen and extrapolated the data to the larger Danish individual,” he said.

“We now have more accurate measurements of the megalodon’s size than ever before. Not only was it larger than we imagined, but its body shape was probably rather streamlined, resembling the proportions of the largest living baleen whales.”

Hydrodynamics point to a slender, streamlined body shape

The study also examined the hydrodynamic constraints on massive marine animals. Researchers found that despite its enormous size, megalodon’s vertebral column suggested it had a relatively slender body shape, rather than the stockier build of modern white sharks. This streamlined form would have enabled it to glide through the water more efficiently.

Dr Siversson said, “by considering the body shapes of whale sharks, basking sharks and giant cetaceans like the blue whale, we concluded that megalodon probably also had an elongated body shape, as also indicated by its slender vertebral column.”

“A stocky body shape like that of a white shark or bluefin tuna becomes energetically quite expensive above seven metres”.

Newborn megalodons were nearly four meters long

Growth data collected from the fossilised vertebrae suggests that newborn megalodons were already formidable creatures, measuring between 3.6 and 3.9 meters in length at birth, and may have competed with adult white sharks for similar food sources.

The appearance of the white shark approximately five million years ago might have played a role in the extinction of megalodon around 3.5 million years ago. As more experienced predators, adult white sharks may have outcompeted young megalodons for food, contributing to the eventual decline of the species.

A deeper understanding of megalodon’s extinction

This new research also provides insights into the ecological dynamics of the time. As a gigantic predator, megalodon’s existence was deeply intertwined with the food sources available in its environment, and the rise of the white shark could have disrupted the delicate balance that allowed megalodon to thrive.

“Understanding megalodon’s biology gives us a clearer picture of its role in the ecosystem and eventual extinction,” Dr Siversson said.

This research marks a pivotal moment in palaeontological studies, enhancing our understanding of one of the most awe-inspiring creatures to have ever roamed the oceans.

The paper published in Palaeontologia Electronica, can be read: https://doi.org/10.26879/1502