New technology has shown the incision marks likely made by humans on the fossilised bone of an ancient kangaroo were in fact made after the bone was fossilised, not while the animal was alive.

The research published in the journal Royal Society Open Science focuses on the fossilised tibia (lower leg bone) of a now-extinct, giant ‘sthenurine’ kangaroo. Found in Mammoth Cave in southwestern Australia around the time of the First World War, the bone was later determined to be hard evidence showing that Indigenous Australians hunted megafauna.

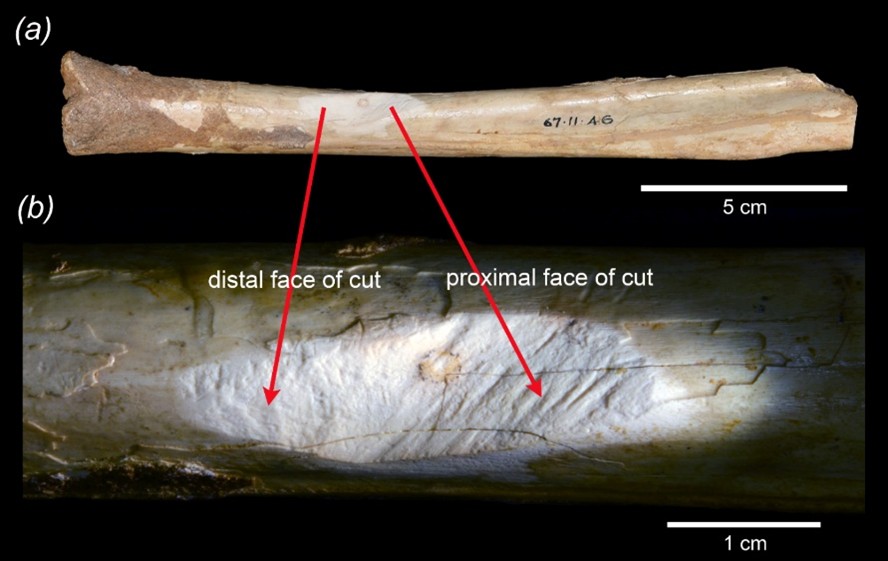

However, new research, led by the University of New South Wales used new technology to retell an old story. The team used high-tech, 3D-scanning (microCT) to look inside the bone without damaging it. They also used updated radiometric dating technology to try to work out how old the bone and the cut really were and detailed microscopic analysis of the cut surfaces.

Their analyses revealed the cut was made after the bone had dried out and had developed shrinkage cracks – meaning it was likely already fossilised when the incision occurred.

The study also analysed a fossil tooth ‘charm’ given by a Worora Nations man at Mowanjum Mission to one of the original researchers from the 1980 paper – Kim Akerman. The tooth belonged to the extinct Zygomaturus trilobus, a type of giant marsupial, distantly related to wombats, that was part of Australia’s Pleistocene megafauna. Although the tooth was received in the Kimberley, in Northwestern WA, its characteristics and composition were a close match with other fossils from Mammoth Cave in southwestern WA.

“The tooth’s presence in the Kimberley, far from its likely origin in Mammoth Cave, suggests it may have been carried by humans or traded across vast distances,” says Dr Kenny Travouillon, one of the study’s coauthors from the Western Australian Museum.

“This implies a cultural appreciation or symbolic use of fossils long before European science did. You could say that First Peoples may have been the continent’s – and possibly the world’s – first palaeontologists.”

So, if humans weren’t solely responsible for the demise of Australia’s ancient megafauna, what may have caused it?

The research team cite evidence that many megafauna species vanished long before humans arrived while others co-existed with humans for thousands of years, but their disappearance often coincides with periods of significant climate change.