On 29 October 1628, Batavia departed from Texel in the Netherlands on its first voyage for the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC)—the Honourable Dutch East India Company. Sailing as part of a larger fleet, Batavia was transporting 341 people, money, and merchandise to Batavia, the Dutch colonial capital in the East Indies (modern-day Jakarta, Indonesia).

Watercolour of Batavia, 1986.

Credit: Ross Shardlow

Batavia was commanded by one of the VOC’s most experienced merchants, Commander Francisco Pelsaert and skippered by Ariaen Jacobsz. The men had little respect for one another; on a previous voyage together, Pelsaert had formally reprimanded Jacobsz after an incident of drunkenness and insubordination.

In April 1629, Jacobsz once again defied orders during their eight-day stopover at the Cape of Good Hope. He took a ship’s boat without permission and went on a drunken spree, visiting other vessels in the fleet and neglecting his duties.

As they sailed towards the East Indies, tensions increased and Jacobsz expressed his anger and vengefulness to Jeronimous Cornelisz—the undermerchant and second most senior VOC official. Cornelisz encouraged the skipper to freely speak his mind and together they cultivated a plan for mutiny. They recruited a small group of accomplices in order to seize the ship and its valuables, which included 12 chests of silver coins, Pelsaert’s consignment of silver wares, and antiquities such as the ‘great jewel of Gaspar Boudaen’.

Less than a month after leaving the Cape of Good Hope, Pelsaert became unwell. While Pelsaert was confined to his cabin, Jacobsz took advantage of a storm to separate Batavia from the rest of the fleet and create an opportunity to test Pelsaert’s authority. On 14 May, Cornelisz and Jacobsz directed their men to violently assault Lucretia van der Mijlen, a wealthy noblewoman travelling to join her husband in Batavia. Lucretia was chosen by Jacobsz because she had previously rejected his advances and she often dined with the Commander. They hoped that if Pelsaert was unable to identify the perpetrators, he would punish the crew as a group, and it would feed dissension amongst more of the men. However, Pelsaert suspected he was being provoked, and thwarted their plans by taking no action.

Shipwreck

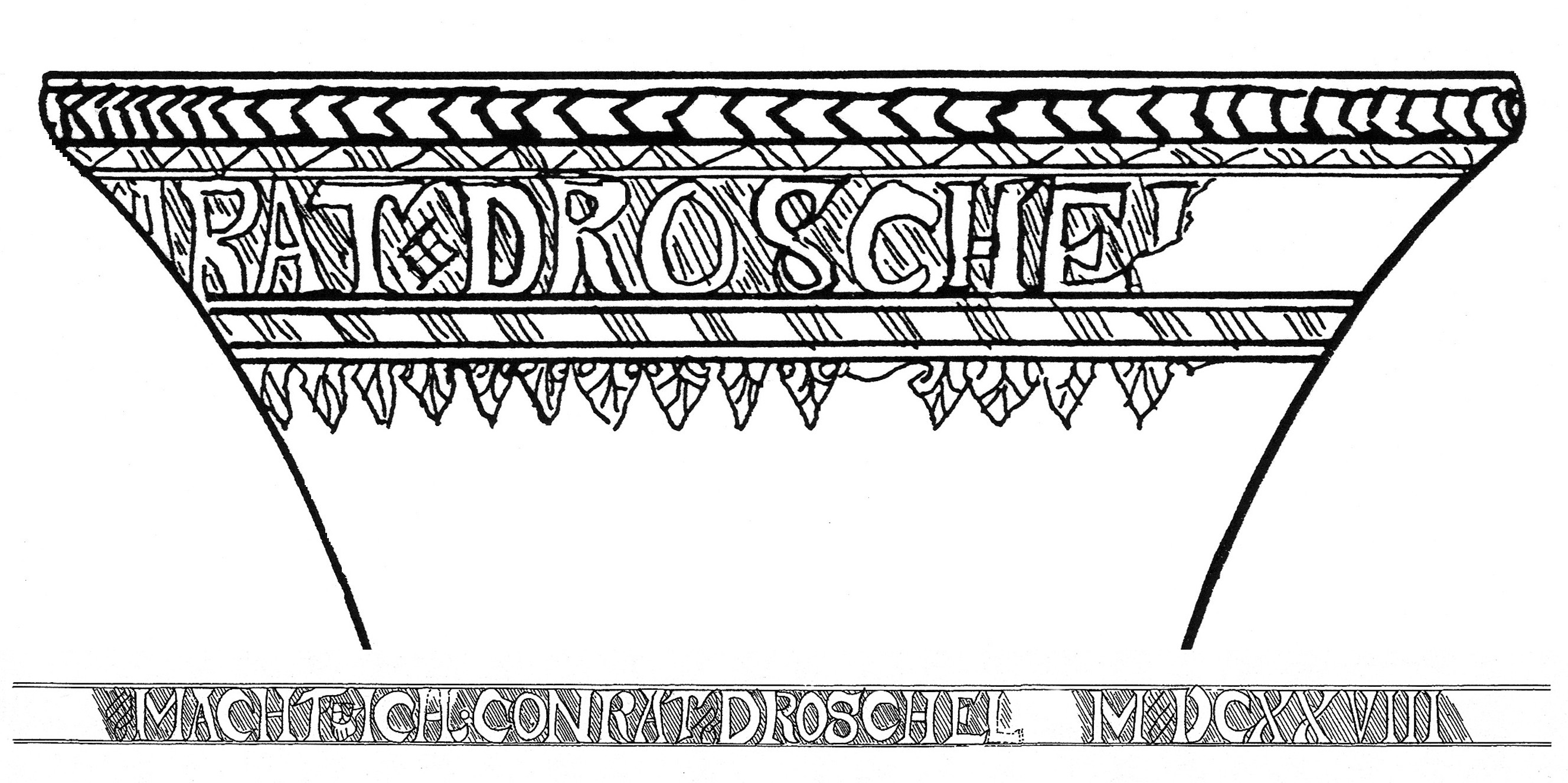

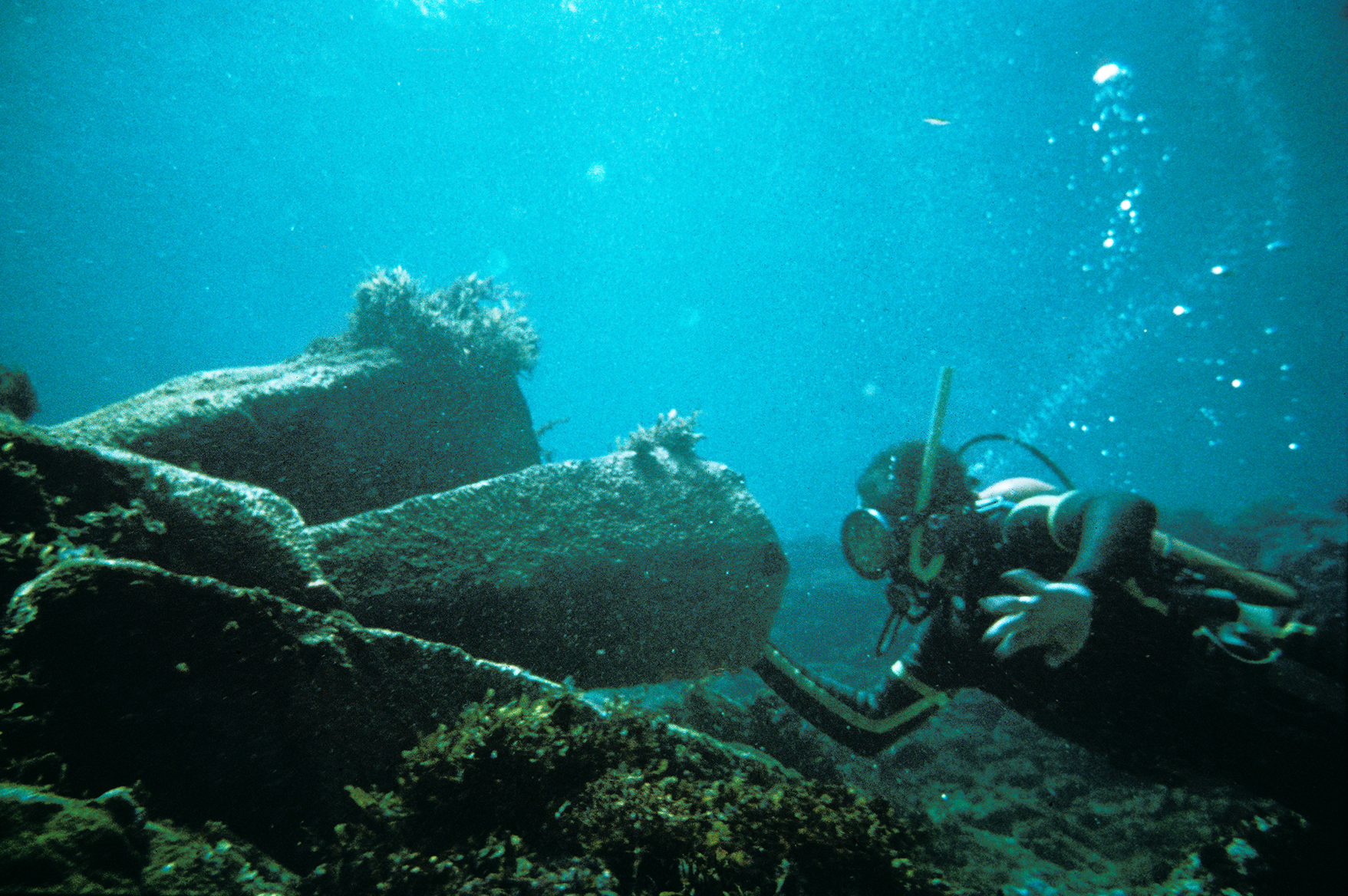

Batavia’s voyage should have been a routine journey for a VOC retourschip (returning ship), which were built to make annual voyages between the Netherlands and East Indies. However, in the early hours of 4 June 1629, Batavia struck a reef in the Houtman Abrolhos Islands at full speed.

Map of the Houtman Abrolhos Islands.

The archipelago lies between 60 and 80km off the mid-west coast of Western Australia.

The crew attempted to dislodge Batavia from the reef, but after several failed attempts, they focused their efforts to getting people off the ship. Under difficult sea conditions, the crew began to ferry people from Batavia to the nearby islands using the ship’s boats. Most survivors were landed on a small sand and coral island (Batavia’s Graveyard, now known as Beacon Island) and about 40 or so people, including Pelsaert and Jacobsz made a temporary camp on a smaller island, which would later be known as Traitors Island.

About 70 people remained on Batavia in the days following the wreck. Some would have been unable to swim and were scared of drowning. Others took the opportunity to freely drink and loot the abandoned ship. Eventually, it was no longer safe to remain on Batavia and people were forced to swim or float on wreckage to the nearest islands. Among them was Cornelisz, who was reportedly the last to leave the ship.

The survivors were ferried to nearby islands and the search for water began.

Credit: Ongeluckige voyagie, van't schip Batavia, nae de Oost-Indien, 1647 | Source: State Library of Western Australia, b1660729_2

Beacon Island and Traitors Island had no fresh water and little food. The survivors had only limited provisions, which were salvaged from the ship or had floated ashore as the wreck broke up. Pelsaert, Jacobsz, and 46 others took Batavia’s only undamaged boat to search the area for fresh water. Unsuccessful, they made the decision to head for Batavia to seek aid.