By the mid-1980s, the timbers were starting to show signs of acid formation following occasional periods of high relative humidity. The Materials Conservation team investigated methods for timber deacidification and opted for treatment using gaseous ammonia. After their successful treatment, the timbers continued to be monitored. While the acidity levels had been stabilised, some timbers remained very fragile. New work began to find a suitable agent that would impart the timber with strength, flexibility and hardness, and be compatible with the earlier PEG treatment.

Following this, in the early 2000s, the Materials Conservation team continued to work on the hull, finding suitable treatments to improve the look and strength of the timbers, particularly where they had been cut with pneumatic chainsaws during the excavation. Around this time, the Museum updated its processes around monitoring relative humidity, and the environmental systems in the gallery were replaced to maintain a stable temperature and relative humidity levels. These changes have ensured the long-term stability of the timbers.

Today, the preference is to preserve archaeological timbers where they are found, rather than removing them. In cases when this not possible, the PEG treatment—used on the Batavia timbers in the 1970s—is still the most common treatment for the preservation of waterlogged, archaeological timbers.

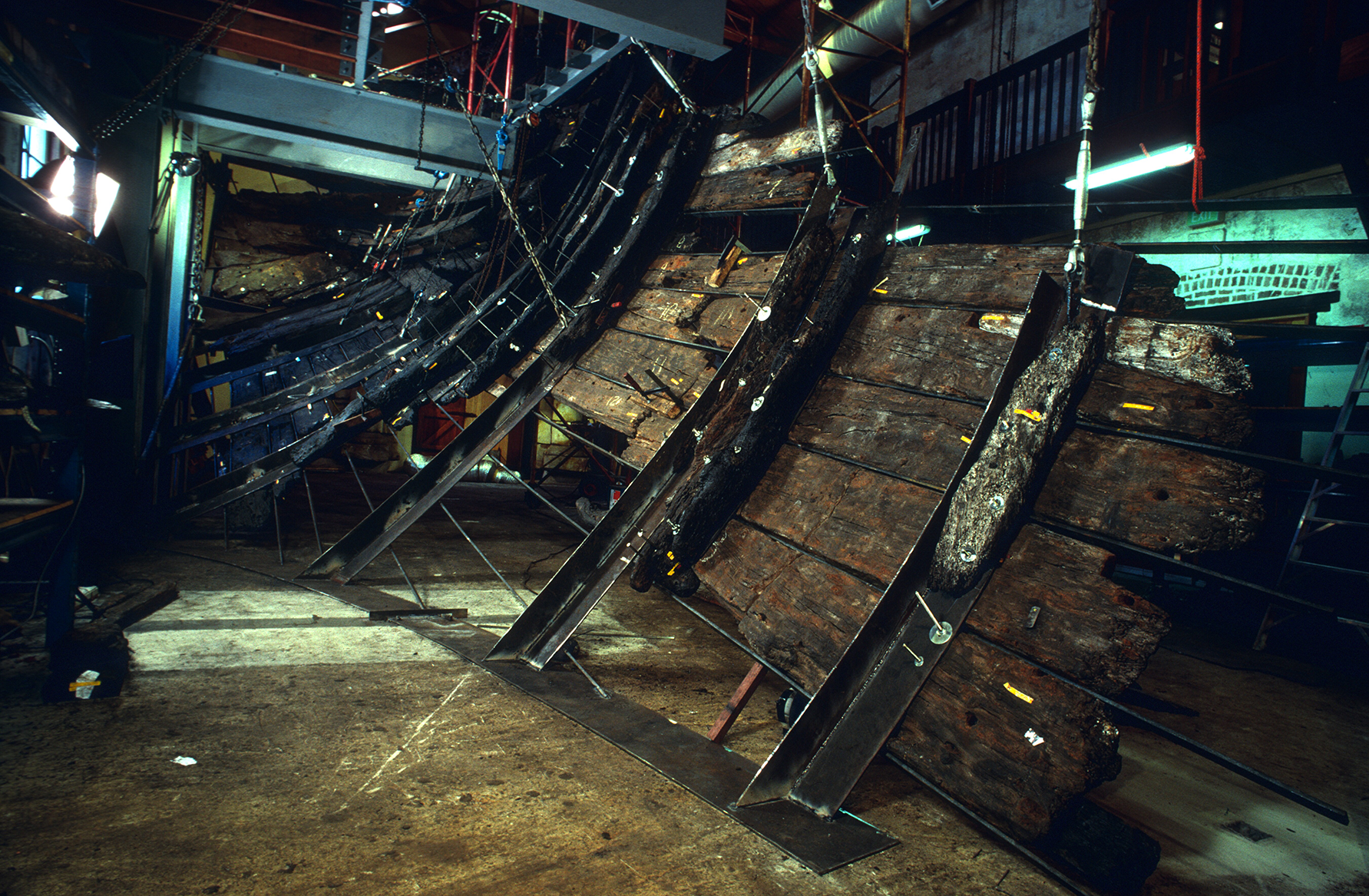

The hull section on display in the Batavia Gallery at the Shipwrecks Museum, Fremantle.

Credit: WA Museum