Fragments of Light, Eclipse Island

This episode takes place on the shores of Eclipse Island, a small, uninhabited parcel of land 17 kilometres south of Albany. Situated at the mouth of Memang Koort, the Menang Noongar name for Albany’s welcoming natural harbour, Eclipse Island was once a brutal playground for gangs of sealers and later a secluded home for lighthouse keepers and their families.

-

Episode transcript

Jessica Machin (JM): You are listening to a podcast from the Western Australian Museum. We acknowledge and respect the Traditional Custodians of their ancestral lands, waters and skies.

Hello, I'm Jessica Machin, working with the West Australian Museum on Stories of the Great Southern, a podcast series, where we explore the histories of the Great Southern region of Western Australia with a diverse collection of local and expert voices to develop a greater understanding of what it means to be Western Australian today and beyond. This first episode, ‘Fragments of Light’ takes place on the shores of Eclipse Island, a small, uninhabited parcel of land, 17 kilometres south of Albany.

Situated at the mouth of Memang Koort, the Menang Noongar name for Albany’s welcoming natural harbour, Eclipse Island was once a brutal playground for gangs of sealers and later a secluded home for lighthouse keepers and their families.

This tiny island has played a significant role in the story of the Great Southern region. Now come with me on a journey through time to see what stories lay beneath the fragments of light dancing over the Southern Ocean.

It's 1968 and a lone light flashes out across the bay. In defiance of the howling arctic winds, a 14-metre reinforced concrete structure stands tall. Inside the lighthouse keeper and his son keep watch.

James Taylor (JT): When I used to get tired, I’d sleep on the curtains underneath the lens, as they were going around. And it was really warm because it was a kerosene light.

JM: James Taylor was eight years old when his family moved to Eclipse Island. His father was employed as the head lighthouse keeper.

JT: Everything I do now, I basically learned from Dad, and I just watched him for years and years. He could fix anything and get anything working. It might not have been pretty, but it worked.

JM: Malcolm Traill, Albany-based historian and Honorary Research Associate at the Western Australian Museum...

Malcolm Traill (MT): Lighthouse keepers were very isolated out there. They used to have fortnightly provisions runs, but of course if the weather was bad then that didn't happen, so they could be isolated for up to a month at a time and really quite desperate.

JT: There’s always seemed to be a turnover of keepers, which you had a lot of people coming and going. Maybe the lifestyle didn't sort of seek them.

MT: The reason the Lighthouse was first thought of on Eclipse was a shipwreck in 1868 and Northumberland had come all the way from England carrying coal and it almost made it, started taking water around Cape Leeuwin and was heading for Albany and it limped along, and it was quite obvious that they were fighting a bit of a losing battle.

But as they were rounding Bald Head, which is the headland just before you come around to the Port of Albany, they struck a rock now called Northumberland Rock, and the ship went down. Ship’s never been found, actually. Then it only took another 60 or so years to actually build a lighthouse on Eclipse Island.

JM: The long overdue kerosene-fuelled lighthouse was erected in 1926 and was the first Commonwealth light built in Western Australia.

Some 50 yards from the lighthouse, atop a ridge neighbouring a rocky cliff edge, sits three small dwellings with adjoining walls. In the vast emptiness of this remote island, the homes are cramped and claustrophobic.

JT: Living on those lighthouses were an exercise in observing human nature. Especially Eclipse Island, it was a triplex. So, if you were in the middle house, you would hear all the noise coming from one side, so you got it in stereo when you were in the middle house.

Whenever Dad made a cup of tea, the Hills family would say, “All I can hear is Ronnie stirring the tea”. And when we saw them a couple of years ago, Debbie Hill said, “Your dad, the way you used to stir the cups”. This is 50 years ago. And she remembered him stirring his cups of tea.

I always remember there were falling outs, and if you got people with difficult personalities to put in that that fishbowl for, you know, years at a time, that was another thing, why my mother became more isolated. It was easier just not to relate to anyone, to just stick to yourself so you don't get into petty squabbles.

Dal Taylor (DT): Having known James’ mother for many years, you know, you idealize it and think how wonderful it would be. The wind and the salt air.

JM: Dal married James Taylor in 1989 and spent many hours speaking with his mother, Evelyn, about her life as a lighthouse keepers’ wife and their time on Eclipse Island.

DT: I remember, you know, when they lived at Cape Leeuwin, I would go down there and you would see this vista out the window of the Southern Ocean, and the waves, and they’d just have the curtains shut.

She would often tell stories of what it was like being a lighthouse keepers' wife on a rock in the middle of the Southern Ocean. You know, this woman who left school at 12 or 13 because of family circumstances in, in Belfast, and she's got to become the teacher of her children through a long-distance education program.

We always joke that his mother got her education by completing the work sets that James wouldn't do. Won him a scholarship to Perth Modern School, which, when he got there, he was surprised to be put where he was, but his mum had done well.

She never, ever liked the ocean. She never learnt to swim. She loved living on the island, but she hated the boat trip. She absolutely hated going in the basket, being lifted from the boat. She used to say that she would crouch down on the floor of the basket with her arms over her head until it was landed.

ABC Documentary Voice over (ABC): There's no natural landing place on Eclipse. The island rises 350 feet out of the water and the granite falls away steeply on the lee side. Even on comparatively calm days, the swell crashes against the rocks, and many boatmen without sufficient local knowledge would be swept against them and smashed to pieces.

JM: In 1968, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation visited Eclipse Island to report on the unique lifestyle of the lighthouse-keeping families.

ABC: All stores and passengers are lifted in a bucket by a crane from the dinghy and then winched up onto the ledge above the sea. This wooden platform on the ledge is the only means of getting onto the island, the somewhat precarious cargo and passenger terminal.

JT: So, when the new crane was built, they were saying to dad, “This is galvanized, it won't rust”. And dad said, “Everything rusts here”. Dad was up the top at the houses and the crank phone went [phone noises]. He ran, grabbed the medicine chest, threw it in the back of the Land Rover and was off, and you could just see a crowd of people.

The personnel coming ashore were in a basket like a, a wicker basket, and they were just hooked on the hook. When it hopped over the pulley on the top, there was no safety catch. The basket flew off and there were two guys in it, a mechanic, and an electrician. They plummeted straight down onto the rocks below. Then they rolled into the water.

That's one of those things that just burnt into my mind as it was yesterday, because Ralph Meekins, it was the mechanic, he’d never been to Eclipse Island before. I remember this. I was in the radio room with Dad, “There's a new guy here, you haven’t met him before” and so, Dad and Ralph having a talk and Dad said, “Looking forward to meeting you tomorrow”. And of course, when Dad met, he was trying to revive him.

For some reason, I just remember a lot of these things as they happened.

JM: It was this fatal incident in 1976 that led to the automation of the light and the removal of lighthouse keepers and their families from the island.

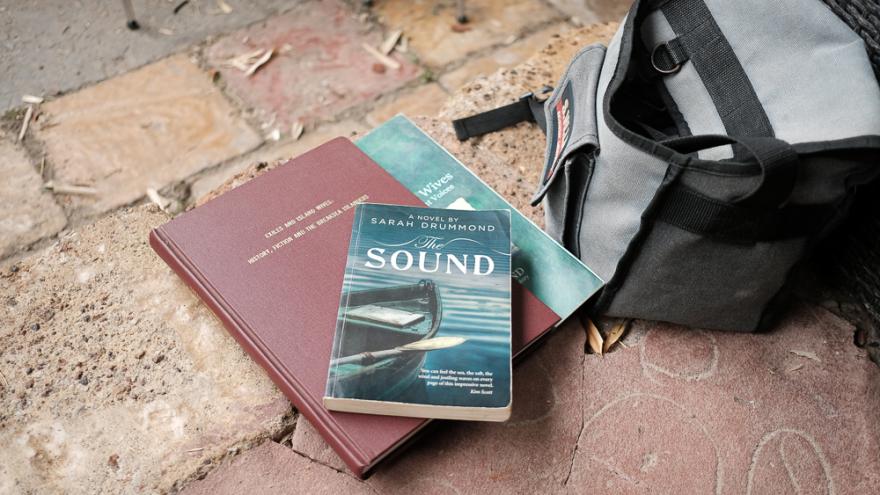

Dr Sarah Drummond is a historian and writer who lives and works in the Great Southern. Her 2016 historical fiction novel, The Sound, tells the story of Wiremu Heke of Aramoana, New Zealand, who joins a sealing boat on a voyage from Tasmania to Western Australia. He is on a quest to avenge the destruction of his village but soon finds himself a part of the violent and lawless world that has claimed the lives of those he’s known. Her first book, Salt Story - of sea dogs and fisherwomen, is a social history and memoir of commercial fishing on the estuaries and oceans around Albany.

Sarah Drummond (SD): I don’t know if you've ever been on the water out there, it’s like, it’s this massive swell coming in and then you get this backwash coming off of, it is just messy. It's like really seriously gnarly. It's quite scary.

JM: Throughout the 19th century, sealers hunted along the rugged islands and bays of the Southern Ocean. Albany’s King George Sound and the surrounding islands, including Eclipse, were peppered with sealing gangs.

SD: I mean, back in those days, it was a [...], primary cause of death was drowning, you know, especially for the sealers. That was a really dangerous [...] dangerous work.

And they quite often were sealing up against those kinds of rocks as well, because that's where they're, they're killing seals, you know, is on those rocks. So, they're coming up to where the swells sort of coming up to the rock and then pushing back again. They used to live on islands a lot. I think that they were probably less vulnerable on islands.

Ross Anderson (RA): The sealers really liked islands because in a sense, they're like a little fort. You know, they could, they could avoid any perhaps retribution from Aboriginal people living on the mainland. They could go over and steal women and come back and they would be relatively secure in the islands because not many of the Aboriginal people on the south coast of Australia had these kinds of sea-going craft. We know that they did visit some islands, but, but it was like a little, you know, watery fort, if you like, with a big moat called the Southern Ocean.

JM: Dr Ross Anderson, Curator of Maritime Archaeology at the Western Australian Museum, explains the sealers’ way of life on the coastline of the Great Southern and stretching into the Recherche archipelago near Esperance where, from the 1820s onwards, hardened sealing gangs of men roamed in search of fortunes to be made from seal pelts.

RA: It was a bit like a gold rush. If you could find an island, you could make a lot of money very quickly. So, some of these cargoes almost equivalent to sort of like a quarter of a million dollars or something in today's money.

Sealing and whaling were really important industries for the Northern Hemisphere industrialized countries. People were running their lighting off whale oil, and furs were also in demand for trade to China because furs were kind of like a prized, you know, like you know, see the king's cloaks and everything. It's like a luxury clothing thing. They were also used to make, you know, as a substitute for beaver fur, making top hats, basically a fashion item.

JM: The archaeological evidence for the sealing industry is very scant. Islands like Eclipse were ephemeral sites. They would arrive, club seals and leave. These were not typically long term or permanent settlements.

RA: There's crazy stories of sealers, you know, just dropping gangs off. So, their modus operandi was to kind of drop gangs off on islands. They would camp there, live there and come back and pick them up, you know, months later, years later sometimes, or just completely abandoned them. So, they were very used to living a very rough life. They would live under upturned small boats that they used, whale boats like little oared boats, and dinghies. So, they had to get onto islands, often quite slopy, granite islands, quite dangerous, some sealers would die in the process of getting on and off of the islands with surf breaking around them. The idea was to have the gang and there would be enough people to go and club as many seals as quickly as possible before the rest of them got scared.

Generally, the sealers would row up to the island wherever the haul-out spot is where they were basking in the sun and, you know, just jump off and run around with their clubs.

Obtaining the seal furs and the pelts is, is quite violent. So, they would basically just have a very solid club of wood, generally and they would just knock them on the head right between the eyes. And that was enough to kill the seal.

JM: On the 25th of December 1826, the HM Brig Amity sailed into King George Sound from the British penal colony in Sydney to lay claim to the Menang Noongar country now known as Albany. Under the command of Major Edmund Lockyer, the settlement of Fredericks Town was established on the shores of Princess Royal Harbour near the modern centre of Albany. Up until this point, the sealers had lived without any sense of higher authority. The relationship Lockyer had with the sealers was a complex one, though the knowledge the sealers had amassed would go on to play an important role in British colonial endeavours in the southwest of WA.

RA: The sealers at Lockyer met in the sound that come from Kangaroo Island and Bass Strait all the way around. They’d explored up to what we now know is the Peel Inlet in Mandurah and as far up as Rottnest Island and been up the Swan River in fact. They’d done a lot of traveling and exploring and they reported, look, there's little boat harbours, there's little places you can shelter. So, they had a very good knowledge of the coast and the water sources.

And in fact, their advice and their knowledge were really valuable and important to that kind of colonisation phase of, of Western Australia because they reported their finds and discoveries to the authorities.

JM: Even so, Lockyer remained wary of the sealers describing them in his journal as “a complete set of pirates that require immediate measures to control them”.

Just two days after his arrival at King George Sound, Lockyer heard that a Menang woman and young girl were being held captive by a sealing gang on Eclipse Island. He sensed an opportunity for a public display of authority in the process of British settlement in the area and sent Lieutenant Festing out to the island to bring both the perpetrators and the victims back to the mainland. Sarah Drummond again...

SD: So, what he did was he kind of put on a show for the Menang people, sent Festing out to rescue them. When they came in, apparently, this great shout went up and the Menang see this boat come in through the heads, through the channel. Took them all day to go out there and get back. Lockyer actually managed to stop the Menang people from going down to the shore to greet this boat because he wasn't sure what they were going to find. And he got all of the soldiers to actually line up and they got Samuel Bayley, the kidnaper. They got him off the boat first and they put him in handcuffs, and they walked him past all of the soldiers, this really theatrical display. And then they brought the young woman back. Lockyer's very words were “I have never seen a person so ill-used". She was in really bad shape. And then they brought the little girl.

The Menang people kind of clustered around this woman. Everyone was sort of teary and crying and, and then they saw the little girl and they went, She's not ours. She belongs with the sealers.

JM: The perpetrator, Samuel Bailey, and the witness, William Hook who had also been abducted from New Zealand as a child into labour on the seal boats, and the victim, the young girl who was never identified, but was given the name Fanny Bailey by Lockyer – after her abductor, Samuel Bailey, were all sent by Lockyer to New South Wales.

The British settlement at King George Sound continued as an extension of the colony of New South Wales until March 1831, when it was handed over to the Swan River Colony and was renamed Albany. For the next 70 years, Albany was Western Australia's main port before the opening of Fremantle port in 1897. Malcolm Traill explains.

MT: Well, the harbour is the reason for Albany’s existence. It was the best natural harbour between South Africa and Port Phillip Bay. Sailing ships coming around Africa in the 19th century really were looking for a safe harbour, literally, so this was the stopping off point on the way to the eastern colonies and then reverse going back to, to Europe.

From that point of view, Albany and Princess Royal Harbour was the harbour in this side of the continent. When Fremantle Harbour was built, a lot of the shipping went away from Albany because Fremantle Harbour was more strategically placed, I suppose.

JM: Western Australia's reliance on the Port of Albany underpinned the construction of several lighthouses in the region including Point King Lighthouse and Breaksea Island lighthouse in 1857-1858 and ultimately, Eclipse Island lighthouse in 1926. Decommissioned in 1976, the original Eclipse Island light now casts an eye out over the museum floors of the Eclipse room at the Museum of the Great Southern. Dr Toni Church, historian from the Western Australian Museum describes the Eclipse light and lighthouse objects on display in the exhibition space at the Museum of the Great Southern.

Toni Church (TC): So, it's the very centre of the Eclipse building and it's the absolutely most eye-catching thing as you walk into the room, surrounded by all the little bits and pieces that made it work from the tools that the lighthouse keepers kept, the logbooks, the bucket that brought people onto the island. But it's really the centre of the entire gallery, just as it was the centre of life on Eclipse Island.

It's quite a beautiful and surprisingly silent machine. And the way the light plays through all of those different lenses, it just throws these really beautiful mini rainbows as it's kind of circling around. You can imagine it being up there on a really cold and windy night on Eclipse Island and just sort of silently keeping watch over the ocean, making sure that everyone stays safe.

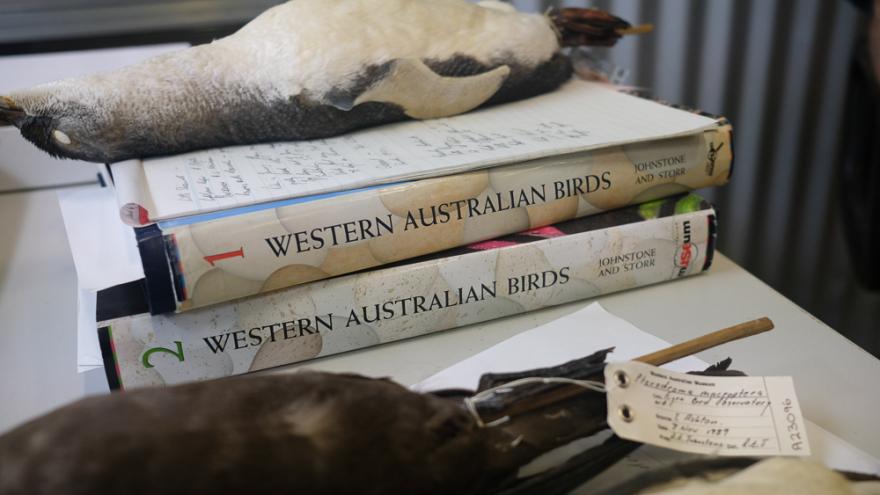

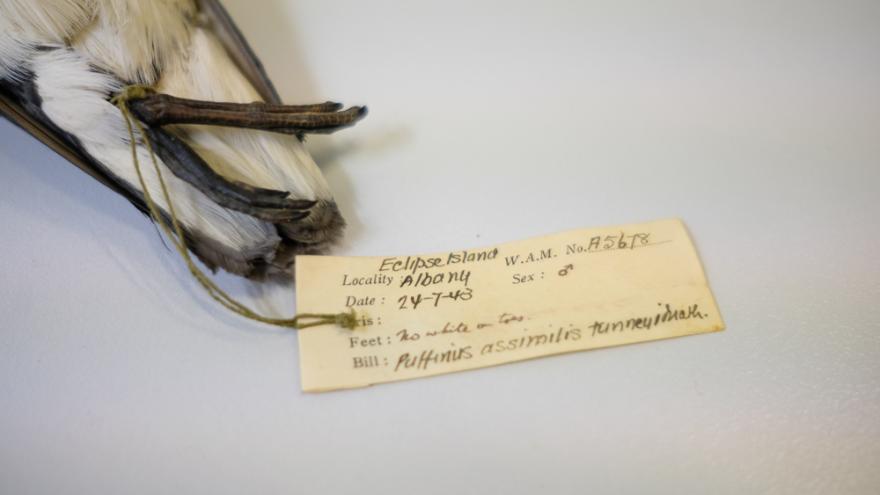

JM: Eclipse Island is Class 1A nature reserve status for the important role it plays in supporting what is estimated at 1% of the world's breeding population of both the flesh-footed shearwater and the great-winged petrel. The Western Australian museum's collection and research centre in Welshpool is home to a collection of over 45000 specimens. Ornithologist Ron Johnstone.

Ron Johnstone (RJ): Museums are a little bit exceptional, but it's, I think people don't realize what's behind the scenes in places like this. It's a, it's a real big eye-opener.

This is the great winged petrel. It's probably the most common seabird on Eclipse Island. This bird's probably in the order of 10 to 15000 breed there. These guys are breeding during the winter laying its eggs in May. This is another one that breeds in burrows or under very dense matted vegetation. After it's bred it tends to go south into the sub-Antarctic and areas of the Southern Ocean, just flying continuously.

They have a strap that's just a huge tendon that runs over the back of the wing like a belt, and it's actually a lock. It locks the wing in position so these things can actually sleep on the wing and travel at big speeds.

ABC: The young birds feed at sea to build up their strength before following the course taken by their parents [bird noises].

RJ: This bird was from Eclipse Island. This bird was collected from Eclipse Island, Albany in 1943. They arrive at the island in around January and there's a fair bit of commotion, they tend to just fly over and around the island.

JM: Much of the WA museum collection from Eclipse Island was sourced by lightkeepers picking up samples and keeping detailed notes in the years the lighthouse was active between 1926 and 1976. In particular, two lightkeepers named Blythe and Newman were prolific collectors of specimens which are still in the museum’s collection today.

RJ: Not only are there seabirds on those islands, but there's a couple of species that also occur. These are residents, things like the Silver Eye’s a resident, the Welcome Swallow, which builds a mud nest in under that the granite overhangs, is a resident there. They're all year round. Kestrels, there's been a couple of pairs of kestrels that bred regularly on Eclipse, and there's a host of other species that are here Vagrants, even a Kookaburra was recorded on the cliffs by one of the ornithologists [Kookaburra noises].

There's been very dynamic changes in sea birds off the West Australian coast, particularly with the increasing strength of the Leeuwin current that brings this warm Icelandic water right down the West Coast and indeed just around the corner into the Southern Ocean.

JM: It is for this reason that Eclipse Island is of global significance, more than just a rock in the Southern Ocean, the island today is a haven for wildlife in a rapidly changing climate, with only degrading remnants of human interaction on the island still in existence.

MT: So, on Eclipse Island today, the, the landing is still there in some shape or form, I believe, and some of the old cottages still exist. I believe that things are pretty well untouched. So, the Island is now pretty much home to the birds and other animals. Nature's taking over.

JM: You've been listening to Stories of the Great Southern, a Western Australian Museum podcast. To explore the stories further, check out our show notes.

This episode was produced by Barking Wolf with Editing and Sound Design by Tom Allen.

Thanks to interviewees James and Dale Taylor, Malcolm Traill, Sarah Drummond, Ross Anderson and Ron Johnston.

Story and research by Mitchell Withers and Tony Church.

Narration by me, Jessica Machin.

Original music by Stephen Richter and Tom Allam, featuring extracts from Here in the West: Eclipse Island provided by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

Stories of the Great Southern was made possible by a Foundation for the WA Museum Minderoo Grant, funded from the Foundation’s Discovery Endowment Fund.

Stories of the Great Southern was produced by Barking Wolf with editing and sound design by Tom Allum.

Thanks to interviewees James and Dale Taylor, Malcolm Traill, Sarah Drummond, Ross Anderson and Ron Johnston.

Story and research by Mitchell Withers and Toni Church.

Narration by Jessica Machin.

Original music by Stephen Richter and Tom Allum.

Featured extracts from 'Here in the West: Eclipse Island' were provided by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

Images courtesy of Tom Allum.

Behind the Scenes

More Episodes

Today’s episode follows the global connections to Albany’s stories and shares how these stories are coming home today.

Today we are in the deep south of WA in a regional centre which has been known by many names across history; Kinjarling, Frederick's Town, Albany, we're here to understand what is in a name?