Meet the Museum: History Detectives

Every object has a story.

Sometimes it’s obvious. Sometimes it’s hidden, waiting to be found, in the smallest of markings or a distant memory.

Join Erica Boyne, head of History at the Western Australian Museum's Collection and Research team, as she reveals the detective work happening behind the scenes to uncover the intriguing stories behind the objects you see on display.

With a background in public history and a focus on oral and American cultural history, Erica brings over ten years of experience in researching and sharing Western Australia’s unique stories.

Don’t let her American accent fool you—she’s passionate about uncovering WA’s abundant history!

-

Episode transcript

Arlene Moncrieff: Welcome everyone to Meet the Museum this evening. Thank you for coming along and, to hear Erika Boyne speak and present on History Detectives this evening.

A little bit of background on Erika. Erika is the head of the West Australian Museum's history department. Her background is in public history with specialization in 20th century social and cultural history.

But don't let her American accent fool you. Erika has spent the last 15 years researching, uncovering, and sharing Western Australia's unique and abundant stories for both Local Government and the Museum.

It's an absolute delight having you here tonight, Erika. Can we please welcome Erika, and I'll hand over for her presentation.

[Applause]

[History Detectives by Erika Boyne]

Erika Boyne: Thanks, Arlene. Welcome again. As Arlene said, my name is Erika and I'm the head of history here at WA Museum. I am a very lucky person who gets to manage a team of six assistant curators and curators, in the History Department. Now, our specialisation, we are all historians, by trade and have all done additional training, in learning how to make history accessible to the public. So, we do serious academic research. We go into primary documentation and secondary documentation and, we hypothesize and, make arguments about the way that history has progressed. But then, my team's central skill that makes us different from academia, is to basically be able to break that down into interesting and consumable bits of information for a wide variety of audiences.

The other thing that makes us really unique, is that we do that using three dimensional objects as our portals for telling those stories. People often wonder, what do you do on a daily basis? So, I'm going to quickly take you through what our day looks like. Then today I'm going to focus on the last bullet point, today, as the research, which is what I consider the most enjoyable, fun, rabbit-hole research, part of our job. But we actually do a lot of other things, and a lot of them are actually behind the scenes, out of sight of the public. And so I'll quickly go over those:

Our main mission is to create a collection, to preserve that collection and to research and share collections of items that tell stories about West Australian people, places, events and cultural norms.

So, when I say social history, this can be really, really broad. It can almost encompass anything. So, there is a human component to almost all sciences. There is human components to all theories. That's what we choose to collect. So, for example, one of my colleagues gave a talk recently on the Brian O'Brien collection, who did a lot of really interesting research and invention on lunar dust. And people asked, why is that not your Earth and Planetary sciences department? The difference between what we collected and what they collect is that they have the lunar dust. They have the pieces of the moon in their collection, and they understand the science behind it. We capture the story behind the person doing the work, and the social transformation that work has had for Western Australia in particular, but also across the world.

We manage a collection of approximately 150,000 items, and this is growing every day. We get offers of donation every day. We research those every day and we decide whether it meets our collection policy.

Our job is to represent the vast and diverse population of Western Australia. We all have very unique experiences, and we're trying to represent those experiences across our entire history.

We are also charged with developing exhibitions, so a lot of people don't realize my small team of six are responsible for over 30% of the content in this new museum. So, all of the social history galleries – Changes, Connections, Reflections and little bits of Innovations – my team were the main drivers of [these galleries], and our collections are really the highlight and the focus of those exhibitions and galleries. And then finally, we are really lucky in that we get to employ what we were trained to do as historians. We get to conduct research and go down those little rabbit holes to find out as much as we can about the items that are coming into our collection. As I'll tell the story today, of some the items that are already in our collection.

So, I'm going to take you down my research rabbit hole today with one particular item to kind of give you an example of some of the work we do and how it kind of manifests into what lands in [the] gallery. So, this is a fabulous child's fancy dress that was created in 1909 and worn to a juvenile fancy dress ball.

Has anyone been to the Connections gallery? So, you know where it sits? So basically, I joined the Museum in the middle of the new museum project, and this was one of the first assignments I had. We were in [the] process of identifying all of the stories we wanted to share, and they were asking all of the curators to just throw up some objects that could help us tell those stories. This was an item that was chosen for Connections gallery, because in a nutshell, its intention is to basically tell the story of how W.A. over history, has connected with the world, and how the world has connected with us. And one side of the gallery is really talking about how our geopolitical alliances have helped us connect to the world, and in particular, that first geopolitical alliance we had when it came with colonization, and we established a British culture here, that's our first major geopolitical relationship. So, this was identified, partially because of its aesthetic quality, but also because of the story as a potential inclusion in that Connections gallery.

But they wanted me to do more research on it. Why do you think you would want me to do more research on it? It had already been accepted into our collection. We already knew some stuff about it. Does anyone have an idea about why I would be charged with doing more research?

Audience member: The portraits

Erika Boyne: Yeah, so there are some really interesting portraits.

So, I'll kind of point out this dress is a very odd dress. I've never seen anything like it because it's a very intricately made silk dress.

All of these flags are actually fabric which have been coloured in and sewn on. And then as you identified, some portraits have actually been cut out of what looks like a book. And then also these little badges and flags have also been cut out of a book of some sort and glued on. Don't ask me what the glue is. My conservation team is dying to know this, but it would mean they would actually have to take some of them off and possibly ruin the dress.

Audience member: They’re paper, are they?

Erika Boyne: So yeah, they're paper and don't ask me what glue they used. I cannot believe they're still stuck on after over 120 years. But they are.

It's a really fascinating piece.

And so yeah, you're right in a way, it is the portraits. Who are these people? What do we know about them? Is there more to know?

Audience member: Do you know who actually wore it?

Erika Boyne: Yes, so I'm going to I'm going to tell you the story right now. But basically, I was charged to do extra research because I am a curator who works in a most fabulous environment, and that's called the digital age. So, this item came into our collection in 1987. That was a time when you didn't have computers, you didn't have Google, you didn't have digital archives available at the touch of a button. The way that we do today. And we have seen a really great opportunity in the history department, particularly through this new Museum project, that when you are touching and considering these items, let's use the resources that weren't available to the curators in 1987 to try and see if we can uncover even more about these stories, so that you can really lift them up and tell more in gallery. So since this item, as you very correctly pointed out, there's a lot of portraits in here. Who are these people? Is there a way I can track that down? What are all of these flags? What do things mean? Sometimes you have an item that's a piece of steel, there's not much you can do for additional research. This item is just waiting for interrogation. And they decided this is actually one that's really worthy of investigation. So this was actually one of the first assignments I had here at the museum. And it's very close to my heart.

So, before I can take you down the research rabbit hole with me, I need to take you all the way back to the beginning to talk about what was included when this was donated in 1987. So it was offered to the history department, in 1987 by a woman who said that it was her grandmother's dress. And according to her, her grandmother wore this costume as a nine-year-old. She was born in Western Australia. Her name was Rita Lloyd, and she wore it to a fancy dress ball at Mansion House in Perth in January 1909.

The donor also told us that she attended the ball as Little Miss Britain. Yeah. Part of the donation also included these two photographs. Now the one on the left, we think it was taken at the actual event because in 1909 photographs were actually still quite a rare thing. It was, something that was actually really only afforded to the wealthy. And you often needed a studio set up in order to get the photographs, because sometimes you were still using glass plate negatives. So we actually think that this was taken at the event, and this is Rita. So, you can see the dress that we have in our collection. And I'll talk about the two other items, but it appears the costume was three pieces and only one of those have survived, but so the donor included the one on the left. Then this photograph on the right, which is Rita in plain clothing at around the same age.

The donation also included these two newspaper articles. Now, the historian inside of me is really, really grateful for this. But also screaming because these newspaper articles have been cut out of a newspaper and pasted onto paper, but they have been completely removed from the context of what newspaper they were published and have no dates. So, wow, they have some really great information in them. At least this first one. I couldn't really understand what year it was published, what day, and what newspapers. So, the first one basically talks about Rita's attendance at this ball in this costume and kind of elaborates a little bit more about how she achieved being Little Miss Britain and what she was trying to project. This second one was a little bit of a red herring for me. It was an article that basically talks about Reginald Lloyd, her father resigning from one of the Perth newspapers and going into business on a new business venture. I couldn't really quite make sense of this, but, you know, any information is good to have on hand. There was just no context in any of our documentation as to why they would have included that.

Additionally, the, the curators at the time did a quick little interview with the donor, and there were some notes that basically indicated they thought Reginald Lloyd was a government surveyor, and there was a tiny little note that he produced documents on the Commonwealth. And that's going to be something to remember later but meant very little when I read this the first time. All right. So, I know what came with this dress. Now. I need to consider whether this is actually viable for the Connections gallery in the new Museum.

So, what do we already know about this dress? I knew it came in in the original package. And then, of course, the curators at that time would have brought the item in and they would have done some of the research themselves. So I started looking at all of the documentation in the research that curators did, outside of what the donor provided us. First of all, what did the curators figure out from the physical markings of the dress? Well, we know who these people are, so I don't know if you can see it very well. I'll use my pointer. But do you see these little tags here?

At one stage this photograph was taken in 2018, at one point in 1987. These were very slightly legible, but they actually had the names of the individuals who were featured in these portraits. Does anyone have a guess based on the design? Who you think these people would be? Audience member: British prime ministers, politicians, generals

Erika Boyne: So. Yeah. Any other guesses? Yeah. Politicians, generals, these are all really great guesses. And had we received the dress in its state today, some of them are very, very hardly legible and some of them have completely faded, which is quite natural. Having been a dress for over 120 years old. Ink is something that is not made to last, and so it inevitably fades. And also, we don't know how it was stored. And so, if it was constantly exposed to light, that increases the rate of deterioration.

In 1987, our curators saw this deterioration, and they actually documented and mapped who all of these individuals were. And then they did the research as to who they were. And all of you are right, in that these individuals are the leaders of each of the British empires overseas possessions in 1909.

So, it just depends on what kind of government this territory employed. You have governors on here, you have governor generals, and you also have prime ministers.

But then you also have these weird, colourful little badges and then lots of different flags. And interestingly, in our documentation, the only description of these is that they were the flags and the coat of arms and badges of the same overseas territories as were represented in the portraits. I don't know why the curators of that time didn't pursue to try and investigate what was what.

Maybe they felt like that wasn't important in the overall story. Or maybe those resources weren't easily available at the time, but all we knew is that they belonged to the over the same overseas possessions.

We also, from the photographs, knew that the dress that we were dealing with was not the complete costume. So over on the left you have Rita's fabulous globe crown, which has Greater Britain in a flag going at the top. And then she has pretty much hand-drawn the map of the world on her globe, and she has highlighted everything that the British Empire ruled in red. And so this is a really clear visual articulation of the expanse of the British Empire. And I'm going to have everyone take a note and remember what country is at the front of that globe.

She also had her Empire staff. Now her Empire staff also has a globe on the top. It is not coloured in the same way that the headdress is, and it has three, red, white and blue ribbons that are, cascading down. These did not survive, unfortunately. So, the donor has no recollection that they were ever in there.

So, the donor has told us that her mother, putting her grandmother put it into storage. So, Rita, and when she passed away, it passed on to Rita’s his daughter, who was the donor's mother. And then eventually, when the donor's mother passed away, it was passed to her, and she felt like she needed to put it in a place that would be able to properly care for it, because she could recognize how fragile it was. So that's why she offered it to us. Now we also have the newspaper articles that are undated but actually have a lot of really interesting information in them. So, this I've pulled a few of the key parts out of it, but one of the articles says one of the most strikingly original costumes of the Lord mayor's juvenile fancy Dress Ball at the mansion House on January 8th was that worn by Miss Rita Lloyd. This little maid of nine summers, nine years old, impersonated Greater Britain, a particularly appropriate choice of character. Seeing that Rita is not only of colonial birth, having first opened her eyes in Golden Western Australia, but has, although so young, also adjourned and various other Britain's numerous overseas possessions in different parts of the world. As she marched in the procession of all the gaily and quaintly dressed children, Miss Greater Britain attracted general attention, and she appeared duly sensibly of the dignity and responsibility of representing these great and growing sections of our vast empire. Very dramatic right?

We also had that other article that I was a little bit more confused by, and I think the main piece that I pulled out of here was that, as they all knew, he who is Reginald Lloyd? The father had resigned his position in the order to join Mr. Teale in business, and he hoped they would be successful. Their first venture, the 20th Century, was on the eye of publication in Perth, and its success was practically assured. Now I again, I didn't really know what to do with this information. I couldn't really figure out how it fit, so I decided that I would kind of keep this on the side and begin my little research rabbit hole, knowing everything that we knew the previous curators had done. And in my attempt to learn more, you I followed three simple steps. And what I found was actually quite surprising because I had assumed the curators would have probably, discovered most things. But, with the access to new archives, I think you'll find it quite incredible what we were actually able to find.

So, the first step in any research process is to confirm the existing information that we have is correct. Using newly available resources.

So, what do we know? Rita went to the ball. We have a newspaper article, although unsourced, saying that she did go. And so, I don't really doubt that it was Rita who wore the dress. We have a photograph of her at what looks to be a ball. That was not really something that I thought we needed to look too much into.

You'll notice that it's called the Lord Mayor's Juvenile Fancy Dress Ball. Well, that makes sense. The Lord, the mayor of Perth, is addressed as the Lord mayor. So, this is all making sense. And we were told by the donor that the ball took place on January 8th of 1909. Now, this article doesn't tell us 1909. So, I need to find a way to confirm it was. But everything's looking really good as to the facts of the donor has given us is correct. Except for one thing.

There is something niggling me. Mansion house. Anyone know where mansion House is in Perth? Yeah, neither did I, and at this point I had been researching Perth history for about ten years. I could not figure out where mansion House would be. So, then that's when I kind of used all the logical steps and those sources that I always use for Perth history. I was going into the State Library archives to see if mansion House was mentioned, or any photographs. Nothing. I went to the state records office to see if it was, in any rate, books. If it was a government house, it might have been mentioned as being constructed or built in the State Records Office archives. Nothing mentioned. I looked in the Post Office directories to see if it was possibly listed as a street address. Nothing there. I then thought, well, maybe it was demolished and it's a building that no longer exists but might still exist on the state heritage list in their inherent database system. So, I searched state heritage lists and there was no mention of mansion House anywhere.

Audience member: Could have been a last name

Erika Boyne: Yeah, well, it could have been a last name. That's a good guess. Well, so what do you do if all of the sources you normally get past history are coming up blank? What do you think my next step was? Okay. Good. Good trove. That's a good one. So I did go to trove and I was finding some similar articles here or absolutely nothing. So, what do you think my next step was to do? Very good. Arlene, when your historical sources don't tell you the answer, go to Google to see if they can start pointing you in the right direction. So, I performed a simple Google search of mansion House, and do you want to know what my first hit was? The definition of mansion House.

So, it explains what is a mansion house. And then the final sentence in that was also with capital letters, mansion House, the official terminology for the Lord Mayor of London's official residence. Okay. So, is there a chance that didn't happen in Perth at all? Did this possibly happen in London? I thought the chances are small because how would this costume it this time?

Get over to London, get back without being damaged, and then be cared for so much? And generally, if you go to London, oftentimes families didn't return. It just seemed really unlikely. But following that source, I decided I would search.

So, someone mentioned trove earlier. Is everyone familiar with what trove is? It's basically a way to search old newspapers. It's run by the National Library of Australia, a fabulous resource if you're not familiar with it, but basically I went to London Newspapers, which is essentially the British version of trove, and all I did was put in Lord Mayor's juvenile fancy dress ball, and I put it in 1909, and this was my first hit, little Masqueraders at the mansion House, the Lord Mayor's Fancy dress ball for children and part of the caption read the Lord mayor gave his ball to children on January 8th, Ding ding ding! And it was attended by no fewer than 1200 little Masqueraders master Francis Truscott, the only member of the Lord mayor's family and fancy dress, appeared as an officer of the Honourable Artillery Company.

I continued to look at all of my results, and I found all sorts of coverage of this event, and I thought the chances that these details line up almost confirm that she's there. And some of these articles were really, really detailed. They detailed who was at the event, what they were dressed as, and what I was getting the impression of is this was a pretty serious event of high London society. And our Rita Lloyd was at this event potentially. Most likely.

(sound of projector screen returning to position)

This is a good opportunity to break. Does anybody have any questions about what I have said so far?

Audience member: The Trove in London, how do you search that

Erika Boyne: So, it's called London Newspapers. And unfortunately, that is by subscription only. So actually, at the time I did not have a subscription to London newspapers, but they give you the chance to do five searches for free. So, I decided let's be very, very clever with our search. And I thought very, very hard about what I was going to put in and let's just say the first five articles I got were all these hits.

And so, I actually didn't need a subscription that time, but it is such a valuable resource. I have gotten a subscription since it's actually really helpful if you are a researcher, in way, because so much of our history, involves people who were not born here, who came here, and when you want to understand people, places and events, their history often starts outside of WA.

And in order to be able to trace them, a lot of that takes you back to the UK. So, I've actually found this really, really valuable, particularly for a lot of our exhibition work. When you're trying to give that lineage or that, origins context to a lot of the people and events that end up shaping our history.

So anyways, basically some of these articles are going into like massive detail. They actually identify individual children's costumes and who they are. So obviously kind of celebrity children and what they dressed as. But the one that got me very excited was this article here, which decided it would pick out what the ten best children's costumes of the whole 1200 kids were, and lo and behold, did I find our little Miss Read a little bit. A quaint but rather burdensome dress was Great Britain worn by Miss Rita Lloyd, who wore a great globe on her head and the national flag on her dress. I now have my 100% proof that Rita Lloyd wore the dress that we have in our collection to a ball, not in Perth, but in London.

Now. That got a lot of questions going through my head, because the original historic significance of this dress, as the previous curators had brought it into the collection, argued, was that this dress was actually a really great, aesthetic representation of what West Australian identity was in the early 1900s. It was fundamentally British.

We were colonized by the British. When you are the colonizer and go unchallenged, it means you get to put in your cultural norms, your laws, your moors, your traditions, everything about Western Australia, with a few, amendments along the way. Because what's face it, some of the clothing for the UK does not really work well in Western Australia. Some of some of those things had to be slightly amended, but largely we were a UK society also was extremely remote in the late 19th, early 20th century. Our main trading partner was still Great Britain. It wasn't the East Coast; the East Coast industry was still really developing. There was no transcontinental railway. Everything that got here had to be taken in by ship. So, we actually saw, the UK as a better trading partner then, the eastern states. So all of our goods came from the UK. And also up until 1890, we had elements of government by people in the UK. So we had this really strong connection.

And the curators felt that the dress here you have a West Australian girl at a West Australian ball coming in dressed as the Empire and trying to show its might. They felt like this was a really clear expression of what a West Australian identity still was in 1909. Well, let's move the ball from Perth over into London. Does that change the meaning of this dress? What do you guys think this dress might mean? Now? Any ideas?

Audience member: [unclear dialogue]

Erika Boyne: Impressionism. Yeah. Yeah, maybe the meaning doesn't change just for location, but, what got me wondering and the questions I was asking is, like you have a West Australian girl in a high society event in London. What is she doing there? There's something going on in this picture that I'm not understanding. And also, why is she choosing to represent the country and the might of the empire in the heart of the Empire? Was she trying to prove something, or was I actually not looking hard enough at what she might have been trying to prove?

And so that's when I decided, I think we need to look at this dress a little bit more to figure out her intentions. So, I basically started then trading this dress as she was a curator. She made and designed this and made choices about who and what and where things went. Let's examine that a little bit closer. Yeah.

Audience member: Where was her mother from?

Erika Boyne: Where was her mother from? UK. Yep, yep.

Audience member: Does one article imply that she lived in many different places?

Erika Boyne: A great way to pick that up. So they say that she lived in a lot of different places. So that's a really good and that's a good analysis to make in that. Did she really feel that she was Western Australia or was she a West Australian girl who was born here and had lived other places?

And at this point we have no record of where those places are. We just have one article mentioning that she did. So, my next step was I started looking at our object a little bit closer. Now when you look at the dress, I mean to me on first impression, it just screams Great Britain, right? It has the red, white and blue.

It has the Union Jack slide. The person at the centre here is King Edward the Seventh. You have; I'm forgetting the name of this flag over here, I think it's called, the King's banner. So, you have base, and then this here is, the white end sign, which represents, maritime or naval, British Navy. You basically have Britain everywhere on first impression.

But then I decided she's put a lot of effort into all of these little things. And we actually haven't mapped those out. We haven't identified them. And is there something happening in the design of this that I'm actually not seeing? So, I first decided to go with some of the more obvious, larger elements to see what she might have been doing.

So of course, we already know we have the king in the middle, but what I noticed is that there was actually two prominent men at the centre of the bodice, and one was right at the neckline and one was right near the beltline. So very central to where the king is as well. And when I investigated who those were, that was actually the Governor-General of Australia at the top.

And then you have, you have the Prime Minister of the day of Australia at the bottom. So I think, Interesting. She's put Australia front and centre. Then I start looking at the flags because I was quite intrigued by the red flag that has the Southern Cross on it, because nowadays that's the naval flag of Australia. And I thought, what a weird thing to pair with the Union Jack almost as a counterbalance, but it is clearly a reference to Australia. So, I actually did some research. And did you know in 1909 what we know as the Australian flag today, the blue flag that was only allowed to be used in highly governmental purposes. So, it actually was not a flag that was flown. Often the red end sign was the flag that was used in civilian purposes. And so, what she's actually done is taken the Union Jack, a clearly English thing, and she's counterbalanced it with what the official flag for civilians in Australia would have been.

Then you start looking at the back, and all of a sudden, I start seeing some more balancing. Down here you have the Union Jack balanced by the Red Ensign. Again, you have the red end sign on one sleeve, and then you have the Union Jack and the King's banner on the other sleeve. What started coming out is that actually, she is almost profiling Australia, not equal to the UK, but pretty dominant compared to some of what I'm assuming the other countries are going to be represented, but I needed to prove that right.

I started looking at the bodice or the dress, the skirt again. You have the red end signed, balanced with the King's banner. And then I started looking at all of the other elements. I basically mapped out everything, and while I was finding one badge and one flag for each of the overseas territories, I was actually really surprised to find I was then finding symbols for each of the Australian states.

Now we all operated as independent colonies up until 1901, but in 1901 we federated. So you would think that it would be a logical thing if she was representing Australia to just have the Australian flag and the Australian badge, but she's actually decided that she's going to put individual states. So, you have Victoria in New South Wales, South Australia, so you have Western Australia here. So that's represented by yellow circle with a swan inside. And you have Tasmania, and these are not appearing on here only once, they're actually appearing multiple times whereas all of the other countries are appearing once and once only. And I will point out that Western Australia actually appears three times the only one to appear three times. So, what am I getting out of this now? On first impression, I thought this was a strongly British dress, but when you actually started mapping and charting out what everything is, she's actually asserting a strong Australian identity in this possibly Great Britain number one. But she's certainly making a statement through these markings that she has in Australian thread and her as well. Now, is our narrative starting to change a little bit?

All of this is starting to be really interesting, but I'm still not really able to make sense of why she's at this high society ball. And I remember that there was that original article in the donation about her father. And generally, when you have young girls or families traveling around in different places, it generally is because of the man's employment. And while I was told that Reginald Lloyd was a government surveyor, that didn't make sense to me. Why he would then be hopping around to all of these places. So I decided I needed to get to the bottom of what Reginald Lloyd did so I could possibly make a little bit more sense about what Rita is doing there and why she might be asserting this, Australian identity in her outfit as well.

So, I did some more searching. Unfortunately, Reginald Lloyd is a very, very common name in this time, so my searches were actually so expansive that I wasn't really able to sort out much. But what I did manage to short was that I kept finding in Perth Original Lloyd, who was a newspaper publisher. I also found a Reginald Lloyd, who, was a plumber. I found a Reginald Lloyd who was, I think, an accountant. But the thing that made me stick to the newspaper, man was that original article which mentioned he was retiring from editing a newspaper that made me feel like I was on the right track. So, we had him retiring from his role and going on his new business venture in 1901.

In that article, I was also finding all of these really weird hits about this Reginald Lloyd being in different parts of the world. So here he's popping up, coming home from Singapore. Unfortunately, Rita's sister got sick with meningitis and passed away. So that hits the newspapers and it actually details him to be formerly of Western Australia Netball, which is South Africa, and Ceylon, which is Sri Lanka. So, I'm seeing him in all of these overseas territories. I'm seeing him in Argentina. I was finding him in, Siam. I was finding him in all of these different places. And I could chart him as a newspaper man in Western Australia up until 1901. Then he's just popping up in all these random territories. But it doesn't say what he's doing.

So that's when I decided I needed to go back to that original article, which is talking about how he's retiring from newspapers. I think I have the right guy, and I'm going back to that statement. As they all knew, he had resigned his position in order to join Mr. Teale in business, and he hoped they would be successful.

Their first venture, the 20th Century, which was the eye of a publication in Perth. So he's publishing something called the 20th Century. All right. Great. So, I go and I Google Reginald Lloyd, the 20th Century, what do you think came up there? A lot of stuff. The 20th century, I think, is probably the title of almost every publication that ever existed. And Reginald Lloyd, wasn't author of some description in lots of places. So I actually really wasn't finding anything that was of substance. And I was getting really quite annoyed because I felt like I had something here that was possibly going to give me the key to what the story was. And so, what would you do now? Anyone have an idea about what I searched next to try and get over this hurdle?

Audience member: Mr Teal

Erika Boyne: Absolutely. Teal is a very uncommon name, and I thought, well, what the heck, let's search Mr. Teal. So, I put teal and 20th century into trove, and I came up with a slew of articles, and it was basically telling me that Reginald Lloyd was a newspaper publisher. He decided to retire, and he went in to work with Mr. Teal to publish a 20th century work called 20th Century Impressions of Western Australia. I then decided to look into what the 20th century impressions of WA was, and it turns out that this was almost like an encyclopedia, which kind of covered all of the geography, the population, the history of WA and teal was the main producer of it, and Reginald Lloyd was marked as the publisher. So, when I had been searching for Reginald Lloyd in the State Library the first time around, he wasn't coming out because he was the publisher, not the author.

So, then I think, okay, well, what (a thank you), I think, what is this 20th century impressions? And it turns out that this is a series that was published by Reginald Lloyd from 1901 to 1914, which covered a country often associated with the British Empire of the time and gave that full history. So, you have Western Australia, Egypt, Siam, Ceylon, British Malaya, Hong Kong, Shanghai, basically the list goes on. And what I started noticing is I'm like, I've got it. I found him in Brazil, I found him in Siam and all of the newspaper articles when I'm finding him, are in the year prior to when he's publishing. So, our Rita Lloyd and her father are tied with this Reginald Lloyd, who was the publisher of this 20th century impressions almost encyclopedia series.

So, I decided to go into the State Library and check out what this 20th century impressions looked like. And what do you think? I found only a few pages in. Does anyone recognize what I'm recognizing? For years? It just dumbfounded me how someone at that time could have afforded books and cut out circles, and she would have had to have bought a lot of books to cut out all of the badges and all of the people, because she would have had to have bought 20 of them, at least.

And that was something that was really not done at the time and would have been insanely expensive unless your father produces them. And it turns out the more I looked into it. Reginald Lloyd is the Lloyd in Lloyd, Great Britain's publication company. And that, it turns out, is why they are attending high society balls in London at the time is because Reginald Lloyd was the major publisher in Great Britain at the time. Oh, I got it! So now what does this dress tell us now? We have picked it to represent the West Australian identity as being British in our galleries, up in connections. Do you think that I can still use it? Yes, we can, but interestingly, it just has a little bit of a different spin because now we see that this is an overt statement that as a West Australian or an Australian, she is part of this grand British empire. But, we also know now she's identifying that there is an Australian identity. That identity is ingrained in a UK tradition. But we then can now use this dress to start transitioning. Well, I thought we would be using it to show no, this is the establishment of a culture and it's British. We actually have a section that goes on and starts talking about why are we participating in World War one and World War Two? Well, we are participating because we are loyal servants of the Empire, which this dress certainly tells. But eventually, come World War Two, we are not so willing participants of the Empire anymore. And a lot of people argue that because particularly in World War one and interwar, we start identifying that there is an Australian identity and it's different from an English identity. It might be based on it, but we are our own people. And it was that exposure through World war that made us see that there was that difference. So, what this dress ended up being is actually a bridge to the next section, where we're starting to talk about the emergence of an Australian identity and how that actually impacts our geopolitical relationship.

So, I wouldn't say it was a disappointment because it wasn't what it was. I actually think that it's a more effective way of going about it. And now through this research process, come out of the rabbit hole. Through this research process, we identified we had a provenance from, and we've been able to correct that. We actually understand this dress and everything it is. And now we can actually use it in more exhibitions as well, because we understand that it talks about that British identity, but it also talks about that Australian identity, and that opens it up for more interpretation in other exhibitions. And that's exactly what we try to do. So that's just an example of one rabbit hole that we go down and we go down on a daily basis. Do we get this far on all of our objects? Certainly not. I think it it's a it's the nature of this dress and how many clues and how many leaves and how many things to investigate. That brought me into what was a very surprising but really enjoyable process. But yeah, we do this for every object that we touch and consider for exhibition now, because there's so much to learn and we actually find that we are we're taking in new items, but we're also having an opportunity to rediscover the collections that we already have.

And you can see this fancy dress if you have it in the Connections Gallery. So, if you go in, you have a beautiful blue room which talks about our connection to the Indian Ocean. We're over in the room that's, yellow. And that's where we talk about our geopolitical alliances, starting with Great Britain, the US, and then more of the, what we call the zone. So, more Pacific, minded alliances, and you'll find it in that area. So, if you want to investigate, please do. And that's it.

(Applause)

Arlene Moncrieff: Will you take questions?

Erika Boyne: Oh yes. Did anybody have any question.

Arlene Moncrieff: This is where you do get the mic shoved up your nose.

Audience member: Thanks. So my husband recognized one of the little cut out circles is an antelope called a kudu. Yeah. And then with the reference back to not telling them the fact that they were in South Africa. So that's in southern African antelope said links to the question that I had. How do you manage? I mean, for me, the message comes at, yes, it's 1909 and this is about the territories of the great British Empire. But now you've got all these emigres in Western Australia, all over Australia, people coming from all over who are now becoming citizens here.

Erika Boyne: Yeah.

Audience member: Which maybe she didn't realize would happen. Yeah. In 1909, being where we are now. And so that links to my question of how do you manage the fact that so many immigrants here bring you their own history? Yep. And if this was a museum, if it's about Western Australia history and socio-cultural issues and heritage, how would you manage these people from other countries who might not have been born here, but now are our citizens have been living here for a few years, and they've got heirlooms or objects of history, historical value, and they donate that like this dress was donated. How do you manage that process if it's not really typically Western Australian heritage? Erika Boyne: Yeah, that's actually a really great question. So, we actually get that kind of offer of donation all the time, and we have more than just the history collection. In our, our, social science areas, our humanities areas, we also have our anthropology and archaeology department who have a world cultures collection.

So, we'll get the request in, and we will have a look at what you're offering now, especially for migration stories. We will take items that represent a life and that people have chosen to bring over as their dear possessions, as a way to tell stories about what they were leaving and then what they were bringing. Because immigrants impact the way the Australian society runs every day. A lot of people don't really want to acknowledge that, but we are what we are because everyone is feeding their culture, their heritage, their way of living into this place all together. And we like to tell those stories. And so very often, sometimes those stories are best told with some of the items that came from where they were and come. Now we usually try and limit that to explaining their direct experience. So oftentimes we won't take everything that someone has brought from South Africa, for example. But if it explains their journey, it explains their transition and explains what they did once they got here and how they impacted W.A, we do take that as part of that holistic story.

You can I can't understand your story without understanding where you came from. Now, sometimes the collections are very big, and we only need a couple of items to explain that. That's when we shifted over to the anthropology department who have that world cultures collection, and they look at those items to see whether it helps you tell stories about the way people and this world live. And so that kind of shifts to a different department. So sometimes collections are split. Most of the time we try and keep them together, and sometimes we have to decline them because they don't meet the collection policies. My department's collection policy is it has to tell the story of something significant to WA and of state significance. A lot of collections don't meet that, but that doesn't mean it doesn't mean meet another collection policy. And if it doesn't meet either of our collection policies, we will always refer you to somewhere who's collection policy it does meet so that you can offer it there, because we acknowledge the value of history and of cultural material. If you throw it away, you never get it back. So, we always we will never say, no, thank you.

We will always say no, thank you, but maybe you should consider these places.

Arlene Moncrieff: Next question.

Audience member: Thank you. Just for the dress I was wondering did your research like demonstrate how much involvement Rita actually had in creating it or whether or not it was like a production of her father.

Erika Boyne: Yes. So no. And that is not a typical of understanding a woman's experience. So, if you want my hypothesis. Rita's mother worked her tail off, and Rita was there choosing some stuff, and maybe her mum had some influence. Maybe the dad was throwing in a few things. But generally, at that time, dads weren't interested. That was a woman's work, and women's work are hardly recorded. So, sometimes those stories are passed down in families and you can kind of grasp the little bits of them, but almost like our sector. There was a there was a huge shift in historiography in the 1970s and early 1980s that went from history is about the grand, the famous white men. That's history. And it shifted to there is value in capturing the everyday experience of everyday individuals and the great and those greats can be whoever you want. So, we really start focusing on what is the women's experience, what is the child's experience, what are migrant experience? What are Aboriginal communities experience? Increasingly now, what are LGBTQ experiences?

There are so many groups that you can capture now, but that shift only happened really decisively in the 1980s. And so, for anything that's really coming in before then, they're not asking those questions. So even if that knowledge existed in the family, it was not interrogated. And we have only what we have.

So, a lot of people want to know who actually made this dress because it was not a nine-year-old. I totally agree, I think that she probably had a stake in the design of it, but I my theory is the mother or the maid, and I think I established through my research, they would have been wealthy enough to have a maid.

Arlene Moncrieff: Next question.

Audience member: Hello. Fantastic presentation. I just wanted to ask this is more of like, a general question, but when do you stop asking questions and when do you stop going back on old artifacts that you kind of thought you had a pretty good picture on and, you know, move on to new other artifacts?

Erika Boyne: Yeah. So, if I find that we're going to use an item in exhibition, and that was brought into our collection in 2012, I look at the documentation and that historiography is the same. The approach to history is the same. The interrogation would have been much more significant, and I trust the approach. It's usually just with our earlier collections that we will always attack it and see what happens. But then unfortunately, all of our items don't have markings like this where we can go, you might have one trademark, and you might be able to find something about that. You might be able to find something about materiality to possibly date it or give it a date range. Recently I had, a bone stool that had a really interesting, label on it that said, made by European hand only. And I was trying to date that. And if you want the history of that, I can give you the full history. I don't know if we have time for that. But it's about the discriminatory policies trying to push Asians out of the furniture making market in the early 20th century.

But I was trying to, I thought, this looks like a mid-century design. It was listed as mid-century, but it's a it's an old record. And so what I was actually able to do is I felt the laws that were put in place were 1904 and then an amendment in 1920. I was trying to articulate how these laws and the effects of these laws actually continued much longer than that. So dating was really important for me. And so that's when I decided this is worth it. And I went down the rabbit hole again, and I managed to find the bones catalogue that that store was sold in so I could date it as being from 1954. So, I could then say these discriminatory policies of the early 20th century and of the White Australia policy are still running and having an impact, even though the laws have kind of gone out of effect. Culturally, it is still running. In 1954.

So, it just depends. And if you run into ten brick walls, you just you accept you're not going anywhere. And it also depends on time. You can't research everything to this degree, but because this was kind of a main feature of a new permanent gallery, we wanted to make sure we got that 100% right. But I did check in with my manager telling him what I was happening. Am I can I go down this hole now? And he was actually quite excited because this had been showcased and, put on display and identified as one of the museum's most 25 most significant items, ever since it was donated. But it turns out they had been telling kind of the wrong story the whole time. So, it's a fun little amendment to make.

Arlene Moncrieff: Next question.

Erika Boyne: Yep.

Audience member: Yeah. I'm just wondering if the glue that was used was, book glue because of, you know, you wouldn't generally have on hand a decent glue that would have stuck for a hundred years. So, I wondered if daddy brought it, from the factory. And it's a very good theory. Again, my conservation team is not wishing for this to fall apart, but they said the minute one of those falls off, you tell me, because they want to test it, they're not going to pull it off and ruin anything. But it's something did fall off. They have very heavily suggested I let them know as soon as possible. Because they're actually amazed it's still affixed. Now, we're going to have to take this off display soon because, reds are the most susceptible dyes to fading, and we don't want to lose this dress. And so, we're going to be changing it out.

And you can also see I thought it would have been the adhesive that would have given way with extra light, extra heat. Nothing has really moved on. The dress, which I find amazing. It's actually the weight of gravity. So, if you guys look at it in gallery, it's starting to pull on the shoulders. And so, we need to wrest it from the light. And then we're also going to need to find a way where we can preserve the shape. We've always stored it upright. But obviously gravity is taking at it. So, the conservation team is actually going to have to custom make a way to store this flat, but without flattening and bending things. So that's going to be their challenge that they've been lined up for later this year.

Audience member: Hi. Have you actually identified all of the badges that are on? Yeah, yeah. Yep. So, in our supplementary document file, you just have this big print out where I have identified and basically drawn and written every. It's basically what I called the mapping process. And I think my colleagues thought I was crazy, but the mapping process actually showed us something that was right in front of our face that we weren't really seeing before. So it was actually really beneficial.

Audience member: You said that the ink faded

Erika Boyne: Ink. Yes.

Audience member: What ink doesn't fade?

Erika Boyne: Poof. There's modern inks that won't fade. I wouldn't be able to tell you. I'd have to ask my conservation team. But this would have been a normal typewriter, so it looks like it was typed in a typewriter. And so, it's just a typewriter? Ink? Yeah, yeah. So, if you guys have old typed written letters that would have been stored in light, they fade. And these ones have faded. So, it's not surprising you can still see a little remnant on some of them, but some of them are completely illegible.

Audience member: I was also going to ask, to what extent do you involve the family, and do you ask the family before you kind of consult all these online and like, archives and things like that? And do you let the family know after you've kind of assembled kind of what you see to be the history behind it?

Erika Boyne: Yep.

So, we usually consult the family when, if we're pursuing something, we work closely with families when we're acquiring things now, and we'll always let them know when there is a product or when their, items are going on display. Generally speaking, you know, like with New Museum, we could not contact every single person whose items were coming on display.

But if it's someone that we have done engagement in consultation with recently, we always make our best attempt to do that. We always document the most current information for contact details. Unfortunately, we couldn't find anyone linked to this person, so we tried. I searched in Perth. They there don't live in Perth, or they have changed their name or there's not listed in the phone book. So we made a few attempts. I made some phone calls. It wasn't this person, so we weren't able to. And I was really disappointed because I actually wanted them to have more of that family history, because obviously someone was very interested in the family tree, and they thought they knew stuff about Reginald Lloyd. And I thought, I have so much more to tell you, but I couldn't track them down. Arlene Moncrieff: Anymore questions for Erica? Well, if not can we please show a round..or give a round of applause for Erica Thanks for sharing the rabbit hole with us, Alice. Erica your passion for this subject is absolutely infectious, so thank you for coming along and sharing that with us this eve. What are you going to put in its place? Was that secret business at the moment?

Erika Boyne: No, it's not secret business. We actually have a young boy's, kind of sailor suit. So, one of the princes was really well known for wearing this very British looking sailor suit. So, the museum of Childhood actually had a replica made. Okay, so the original is too sensitive to put on display, but we will display the replica while she rests, and we'll tell the same story just with a slightly, in my opinion, slightly less evocative item, but it still delivers the same message that we're delivering in galleries.

So, we'll switch them out and she'll rest for a few years, and then we can switch her back in. Right. Okay. Thanks, Erica.

More Episodes

Join Corey Whisson, the WA Museum’s Collection Manager for molluscs, as we dive into the fascinating world of marine animals that sting, shock, or stick you when you least expect it. You'll learn how to spot them, avoid them, and appreciate them (from a safe distance, of course).

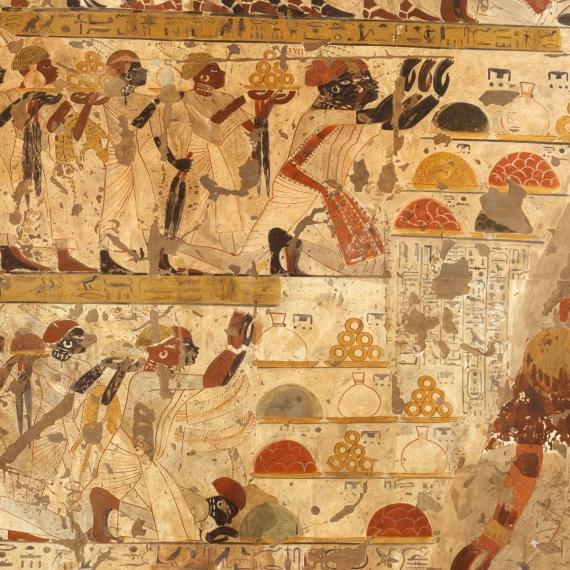

Visiting Egyptologist, Nubiologist and archaeologist Dr Julien Cooper of Macquarie University shares insights into the workings of Egypt’s gold industry, drawing on ancient texts and new archaeological surveys in eastern Sudan.

Join Bryn Funnekotter, a biotechnologist at Kings Park Science, as he shares how and why we are helping conserve some of WA’s most endangered native plant species.

Join the WA Museum Boola Bardip Learning & Engagement team for an exclusive behind-the-scenes look at how we create unforgettable experiences!

Join leading barrister and former President of the National Native Title Tribunal, Raelene Webb KC to explore the connection between art and law in the Spinifex People's pursuit of native title recognition.