Ship

Glenbank

Country of origin

Finland

Built

1893

Rig

3 masted barque

Tonnage (gross)

1481

Port Departed

San Nicholas, South America

Port Destination

Balla Balla, Western Australia

Wrecked

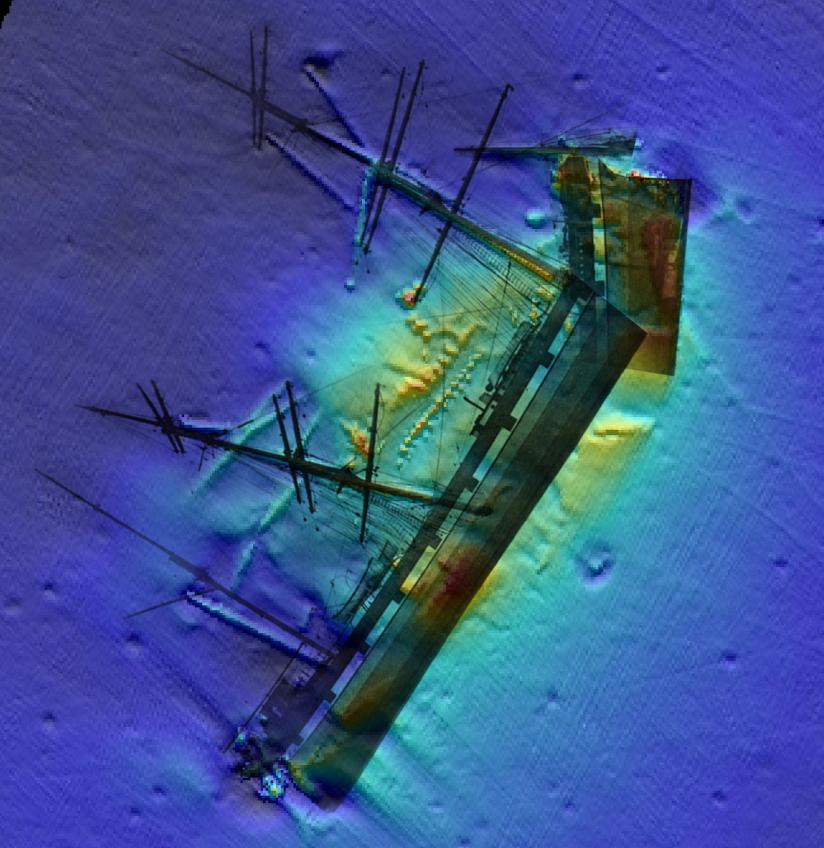

6 February 1911, off Legendre Island

Discovery

Kevin Deacon, Johnny Debnam, Tom Radley, Justin Leech, and Luke Leech

Protection

Commonwealth Underwater Cultural Heritage Act 2018

History

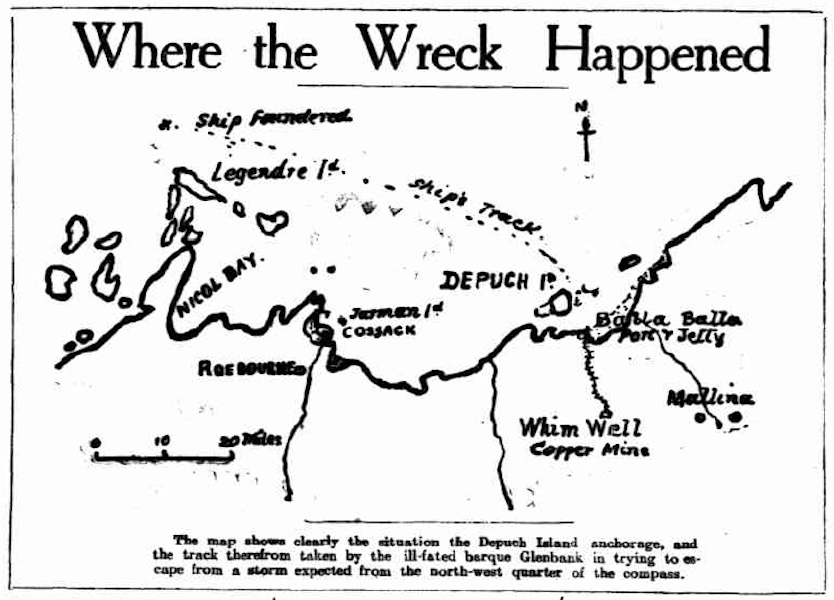

In November 1910, the steel barque Glenbank arrived at Balla Balla, Western Australia. The ship had been chartered by Whim Well Copper Mines Ltd to transport copper ore from Balla Balla to the United Kingdom.

The Whim Well Copper mine was located about 20 kilometres inland from the coast. A private, single-track, narrow-gauge railway was used to transport the copper ore from the mine to Balla Balla jetty, which had been leased to the company. At the jetty, the ore was put on to lighters (a type of flat-bottomed barge) and ferried out to the anchorage near Depuch Island. There, the ore was loaded on to cargo ships, such as Glenbank. This would have been a manually laborious and time-consuming process; it could take months to load a ship.

Glenbank had 20 crew members (mostly Russian, Norwegian, and Finnish) and was under the command of Finn, Captain Fredrik Moberg.