Ship

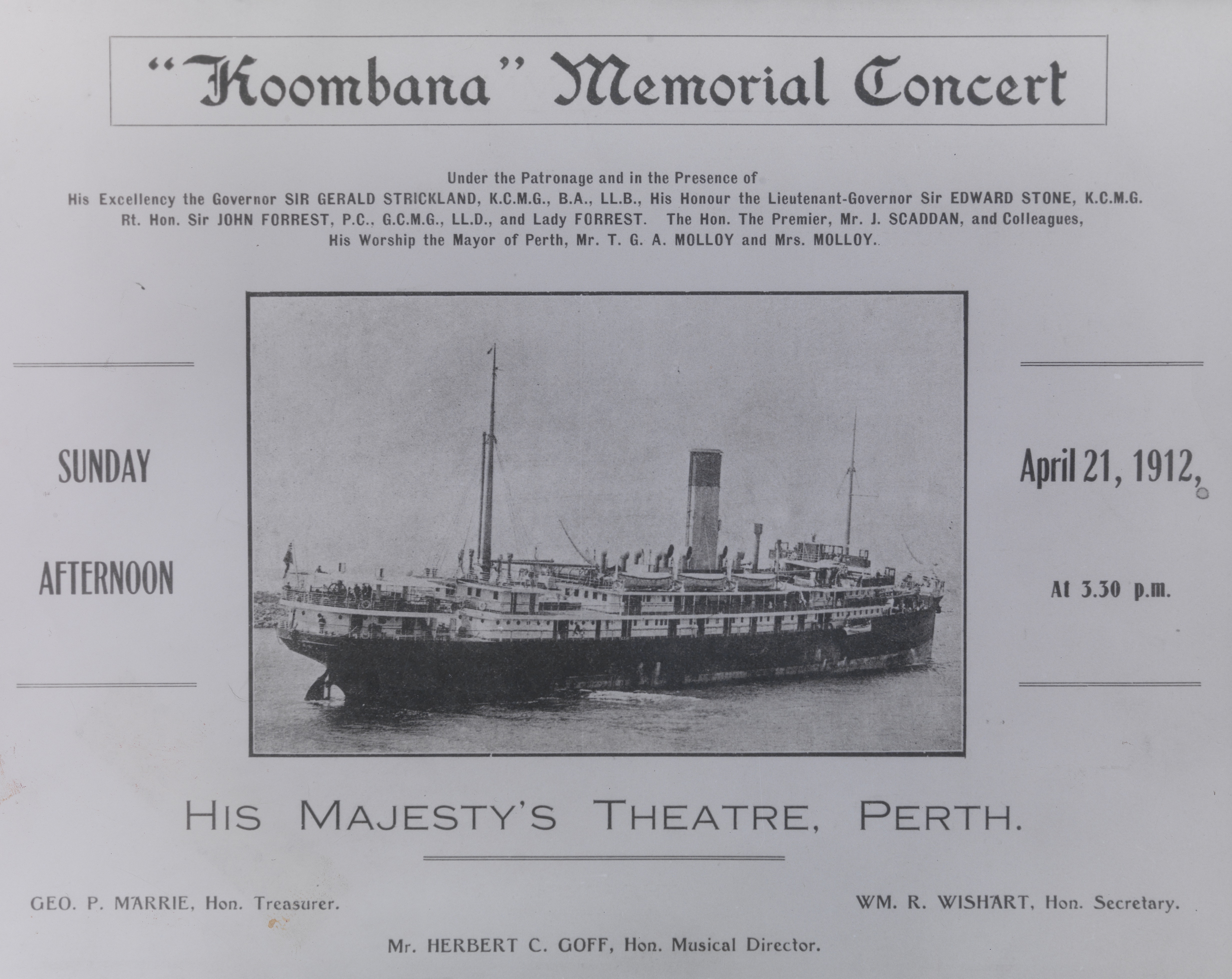

SS Koombana

Country of origin

Australia

Built

1908

Rig

Single-screw Steamship

Tonnage (gross)

3668

Port Departed

Port Hedland, Western Australia

Port Destination

Broome, Western Australia

Wrecked

20-21 March 1912, north of Port Hedland

History

Koombana was a luxury steamer that was purpose-built by the Adelaide Steamship Company for the north-west Australian coastal passenger and cargo trade. The ship was fitted with modern amenities such as refrigeration and electric lighting, reflecting the success of the region’s rapidly growing pearling and pastoral industries.

Koombana worked the ‘Nor’-West Run’, transporting passengers, livestock, and cargo between Fremantle and Wyndham, with stops at Geraldton, Denham, Carnarvon, Onslow, Cossack, Port Hedland, Broome and Derby. The cyclone season between November and April, large tidal range (up to nine metres) affecting northern ports, shallow port entrances, poor port infrastructure, and tight schedules made it a challenging route. In three years of service, Koombana scraped sandbanks, ran aground several times, struck a reef, and had two onboard fires.