For Albany-based artist and former environmental scientist Chelsea Hopkins-Allan, that means getting up close. Really close. Not just to the tiny world of moths she draws in exquisite detail, but to the systems, species and unseen stories that shape our understanding of nature.

As part of her ART ON THE MOVE Activating Collections residency at the Museum of the Great Southern, Chelsea recently spent three weeks at the WA Museum’s Collections and Research Centre (CRC). She expected a brief visit, maybe a few photographs. Instead, she was welcomed into the entomology lab and given the opportunity to work closely with Terrestrial Invertebrates Curator Nikolai Tatarnic, exploring specimens down to the scale of individual hairs and dust-sized wings.

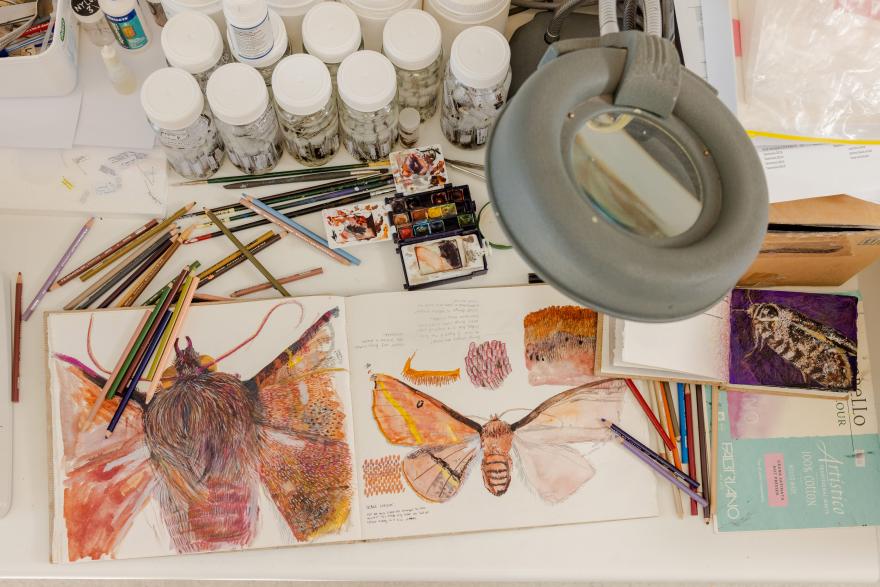

The tools available in the lab allowed her to go far beyond what a photo or field guide could offer. She accessed dry specimens, reference species, CT scans, and even boxes of moths from Albany that have yet to be formally catalogued. She learned to use a stacking camera, viewed microscopic structures and began to draw individual scales and hairs, translating science into an intimate visual study.

“It’s such a privilege to be here and see it all up close. I’ve had access to things most people never get the chance to experience and now I want to find a way to share that feeling, while also showing just how important these tiny lives really are.”

Chelsea’s shift from science to art came during a period of physical illness, when she found unexpected comfort in the moths gathering at her back door. Drawn to their delicate beauty, she began to observe them more closely, learning their scientific names, their roles in ecosystems and their almost-invisible presence in everyday life. That personal curiosity soon revealed a broader gap - we know surprisingly little about these species, despite how essential they are.

Moths are pollinators, decomposers and a vital part of the food chain. Often camouflaged, dismissed as pests or overlooked entirely, they are easy to miss. Some species go extinct before we even know they existed, and if we don’t know they’re there, how can we protect them?

That lack of awareness, Chelsea says, is a symptom of modern life.

“We’re living in an age of information overwhelm. There’s so much data, so many reports and warnings, that it becomes too much to process. Art can cut through that. It’s not about oversimplifying the science, it’s about helping people feel something first.”

Chelsea’s residency is part of a broader initiative to connect scientific collections with community creativity, and her upcoming work at the Museum of the Great Southern will share that experience with others. Through UV black-light spotting, citizen science sessions and art-based activities, she hopes to create an accessible way for people of all ages and abilities to engage with local biodiversity - especially the species we rarely think to notice.