Survivors

After Stefano broke apart, seven of the crew made it ashore: Carlo Costa, Michael (or Miho) Baccich, Tommaso Dediol, Giovanni Lovrinovich, Domenico Antoncich, Fortunato Bucich, and Giovanni (or Ivan) Jurich. The day after the loss of Stefano, they made the decision to walk north in search of other crew and provisions. Jurich was left behind since his feet were too swollen for him to walk.

On their trek, they found another two other survivors washed up on the sand, Nicolò Brajevich and Diodato Vulovich, as well as a small quantity of provisions. The eight of them returned to Jurich and after resting, the whole group made the journey north. Using the wreckage from Stefano that had washed ashore, the survivors set about making a shelter and camp.

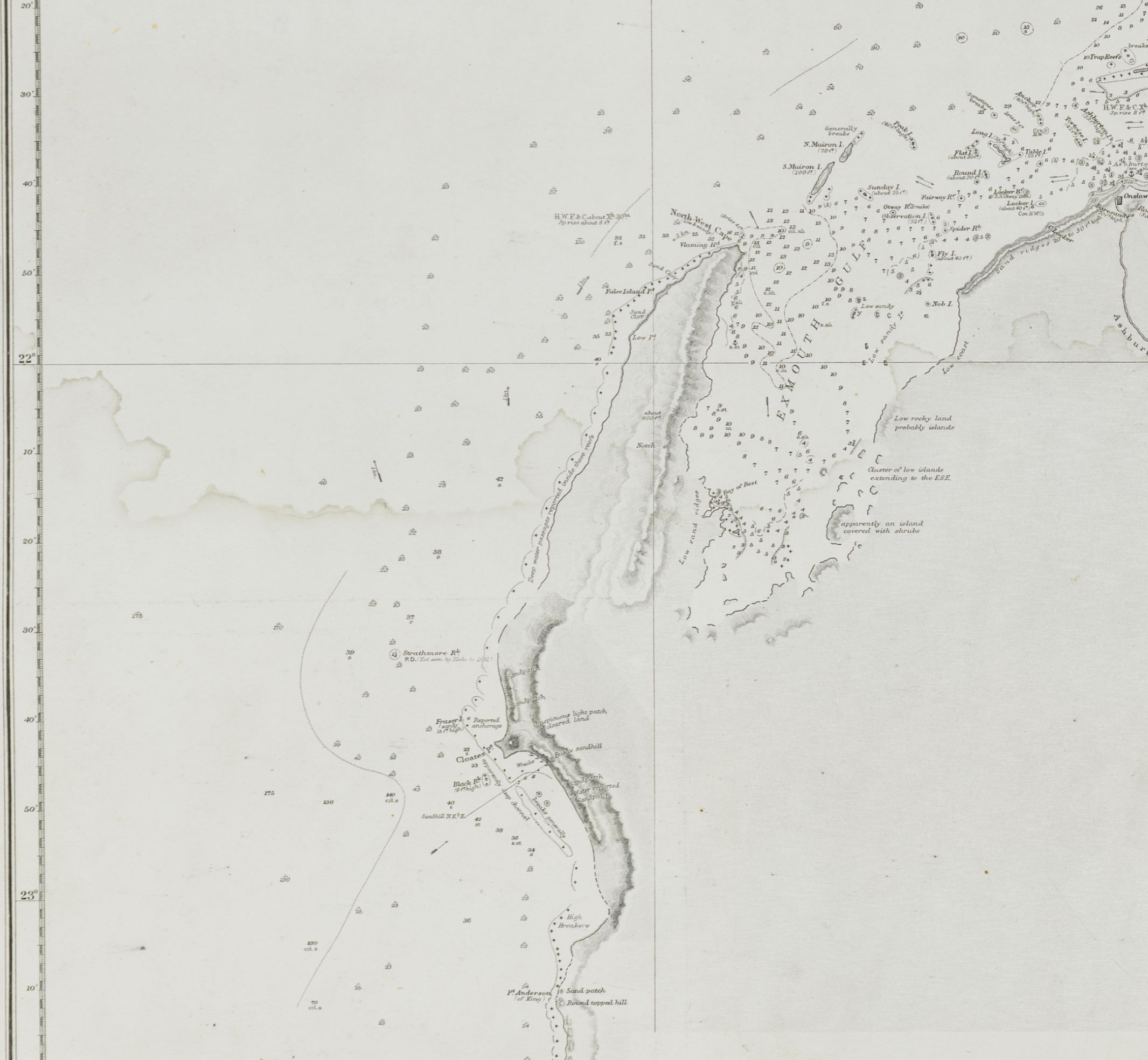

On 31 October, a small group of Aboriginal people approached the temporary camp. They gave the survivors some food and a map showing the north-west coast of Australia. With this, Costa determined they were not too far north of the Gascoyne River and rallied the crew for the walk south, parting ways with the Aboriginal people who had aided them.

As they went south, the group separated, with three crew too exhausted to continue. Again, both groups were aided by Aboriginal people. They were eventually reunited with each other, and a tenth member of the crew, Giuseppe Perancich, who had come ashore further south and had been living with a group of Aboriginal people.

After heading further south and not finding the river, they eventually reunited at the sites shown to them by the Aboriginal people who had helped them days before. They remained there for many days, but in late December a violent storm disoriented and separated the group, contributing to the deaths of Perancich and Vulovich.

By the end of January 1876, all but two of the ten survivors had died. Baccich and Jurich headed inland, looking for the Aboriginal people who had assisted them previously. After finding them, the two men were nursed back to health and lived with the group for about three months. Some of the Aboriginal people had previously worked with the pearler, Charles Tuckey and, knowing his route, they took Baccich and Jurich north to intercept Tuckey near Exmouth Gulf. On 18 April 1876, Baccich and Jurich were picked up by the crew of Jessie and sailed for Fremantle, where they arrived on 5 May.

Studio portrait of Miho Baccich and Ivan Jurich, about 1876.

State Library of Western Australia, 8324B

Before departing Australia, Baccich and Jurich returned to the north-west coast, to present gifts to the people who had kept them alive. In August, they finally began their journey home, arriving in Dalmatia in October. Baccich commissioned a priest, Stefano Skurla to document their story and his manuscript (completed 1876) is the main contemporary evidence for the story of Stefano.

Thalanyji, Baiyungu, and Yinggarda lands

The surviving crew of Stefano travelled through the traditional lands of the Thalanyji, Baiyungu, and Yinggarda peoples.

With no knowledge of the local environment and having been wrecked at the beginning of Western Australia’s hot summer period, Stefano’s survivors relied heavily on the Aboriginal peoples they encountered for shelter, food, fresh water, and eventual reconnection with Europeans. Through their long custodianship of the lands and sea in this area, Baiyungu, Thalanyji, and Yinggarda peoples today maintain knowledge of the life-sustaining freshwater soaks and food resources of this country, and the traditions and stories of their ancestors.

The Skurla manuscript contains very little information about the individual Aboriginal men and women who assisted the shipwreck survivors, and guided them on their journeys up and down the Nyingaloo (Ningaloo) Coast. The names of two young men who specifically cared for Baccich and Jurich are provided. Jacki was a young, single man of about 20 years who cared for Baccich, and Jimmi, another single man of about 30 years of age, cared for Jurich.