Ship

Trial (sometimes Tryall or Tryal)

Country of origin

England

Built

Possibly Portsmouth, England

Rig

Ship

Tonnage (gross)

500

Port Departed

Plymouth, England

Port Destination

Batavia, East Indies

Wrecked

25 May 1622, Trial Rocks

Discovery

Eric Christiansen, Dr Naoom Haimson, David Nelley, Alan Robinson, and John MacPherson

Protection

Commonwealth Underwater Cultural Heritage Act 2018

History, 1621-1622

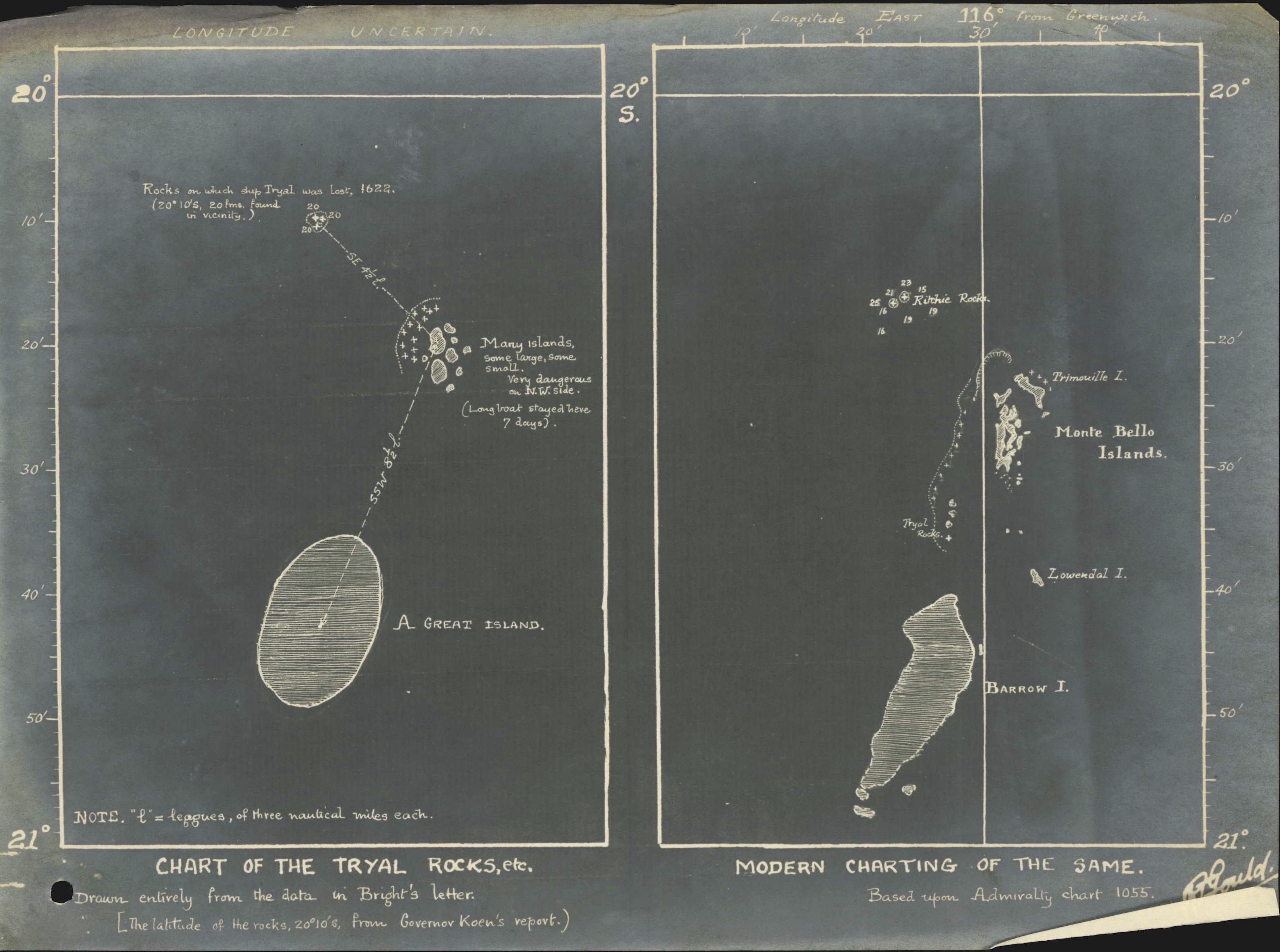

Carrying goods for the English East India Company (EEIC) and 143 people, Trial departed Plymouth, England on 4 September 1621 bound for Batavia in the Dutch East Indies (present day Jakarta, Indonesia). The ship’s Master, John Brookes had been instructed to follow the new Dutch shipping route known as the Brouwer Route. After departing the Cape of Good Hope, Trial initially sailed south before turning east to take advantage of constant westerly winds in the high southern latitudes.

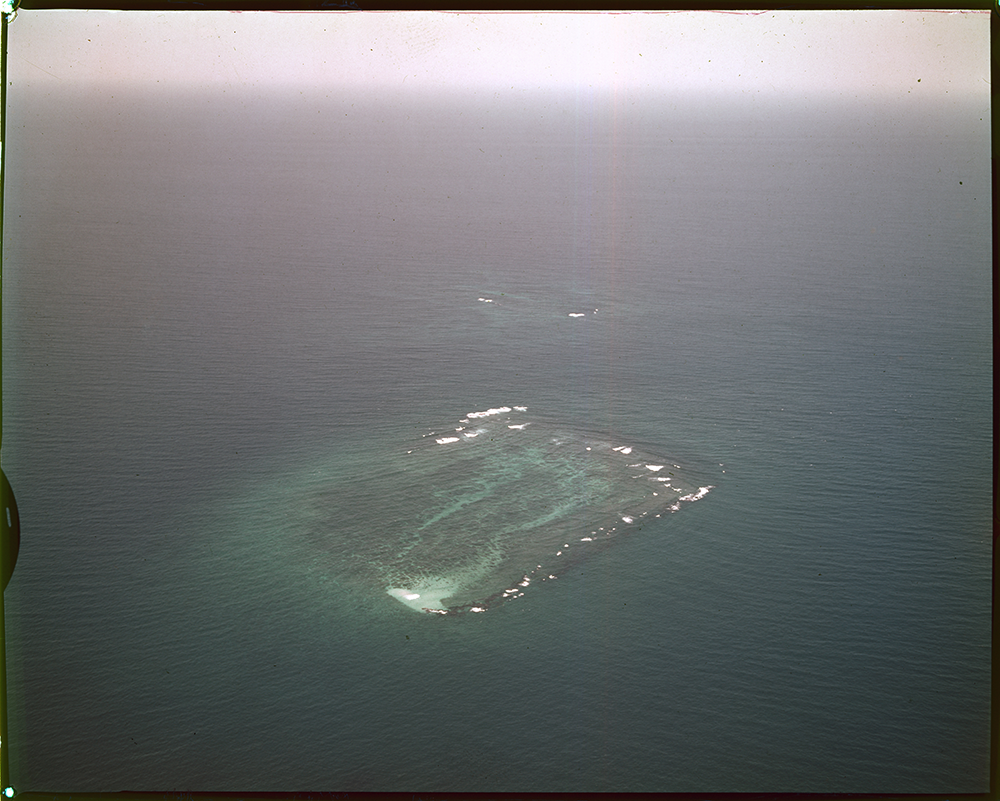

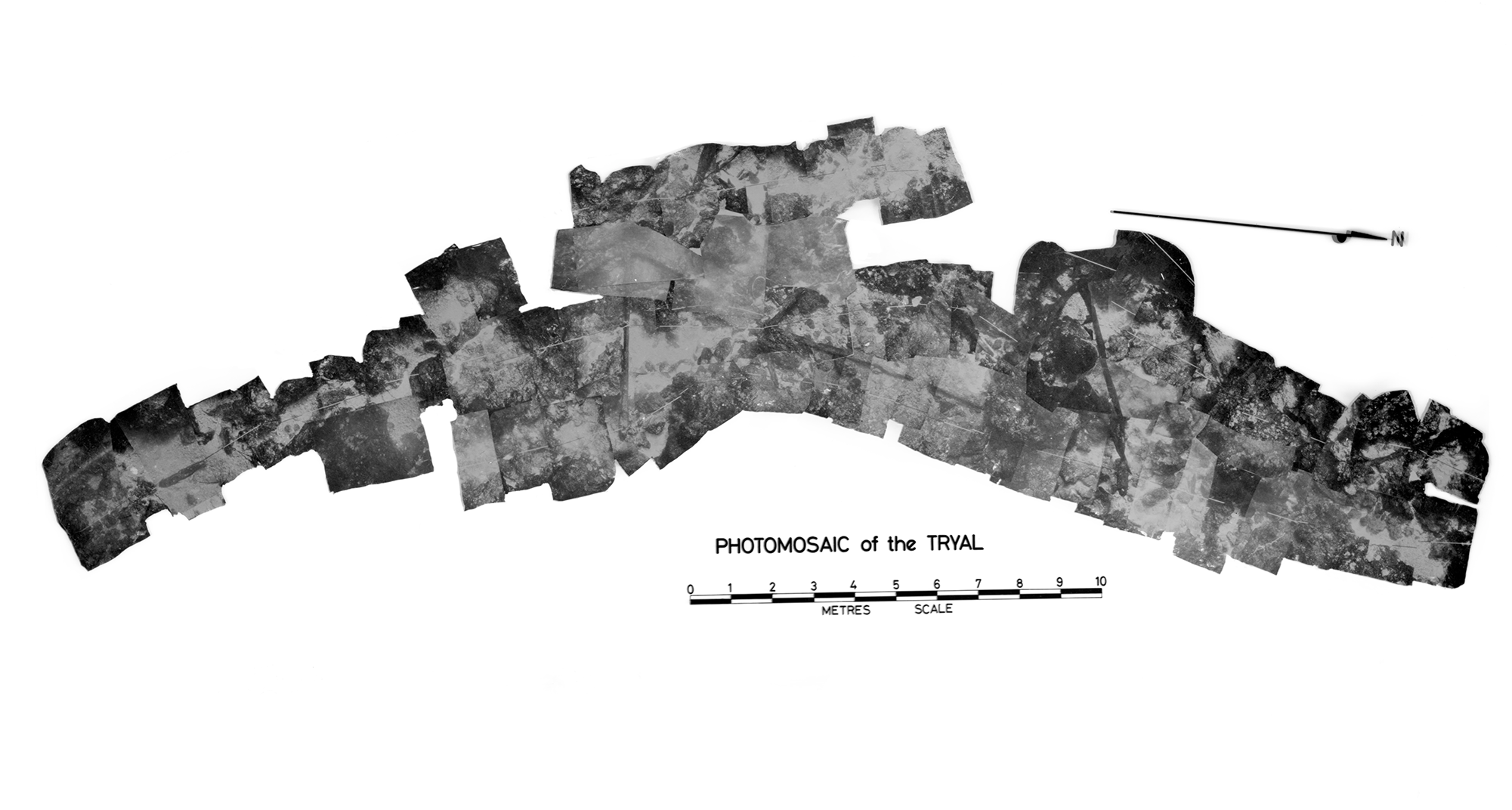

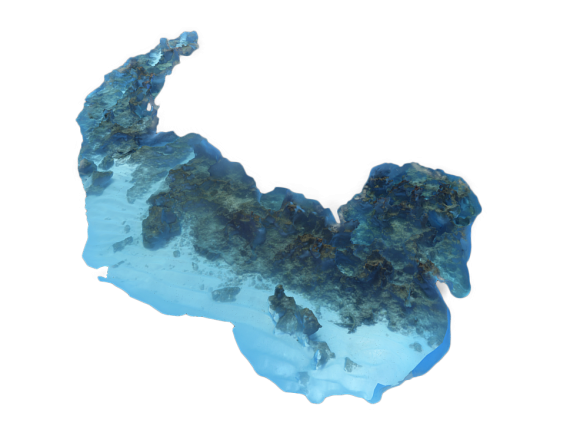

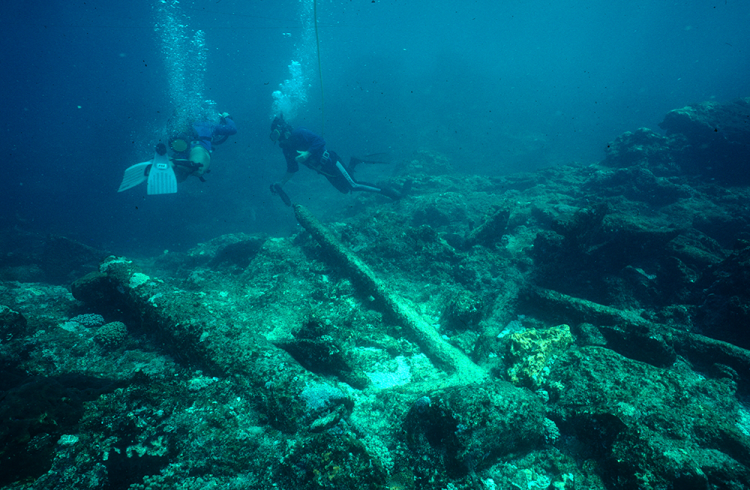

Shipwreck

On 25 May 1622, Trial struck rocks off the remote northern coast of Western Australia. More than 100 people drowned as the ship broke apart. Ten people, including Brookes, managed to escape aboard the ship’s skiff. Another 36 people survived on Trial’s long boat, under the leadership of Merchant Officer Thomas Bright. Both boats travelled separately to the East Indies, where Brookes and Bright each recorded their own, conflicting accounts of the disastrous loss of lives and company property.