Meet the Museum: Spines, Stings and Shocks!

Summer's almost here - but what's waiting beneath the surface of our beaches?

As the weather warms up, many of us head to the coast to swim, surf or simply soak up the sun. But while you're enjoying the ocean's beauty, have you ever wondered what's hiding just below the surface?

From venomous spines to electric shocks and stealthy stingers, the ocean is home to some incredible — and occasionally dangerous — creatures.

Join us for a relaxed, eye-opening session where we’ll dive into the fascinating world of marine animals that sting, shock, or stick you when you least expect it. You'll learn how to spot them, avoid them, and appreciate them (from a safe distance, of course).

Whether you're a swimmer, snorkeler, surfer, or just a fan of the sea, this talk will speak to your curiosity (and could save you a sting!).

Featuring Corey Whisson, the WA Museum’s Collection Manager for molluscs, who will share stories from his travels and insights into these amazing creatures.

Meet the Museum

Are you curious about the fascinating world behind the scenes at the Museum? This monthly program delves into the less visible parts of the Museum’s work, as scientists, researchers, historians and curators share their expertise and passions.

-

Episode transcript

Voice Over: Welcome to the Western Australian Museum Boola Bardip talks archive. The Museum, Boola Bardip, hosts a series of thought-provoking talks and conversations tackling big issues, questions and ideas, and is delighted to be able to share these with you through the talks archive. The talks archive is recorded on Whadjuk Noongar Boodjar. The Western Australian Museum acknowledges and respects the traditional owners of their ancestral lands, waters and skies.

Arlene Moncrieff: Welcome everyone to meet the museum for the month of October, called Spines Stings and Shocks with another by-line, I see Corey, dangerous marine animals. So, I'd like to welcome this evening Cori, from our, science team ,our aquatics zoology team, over in Welshpool and, he's here to give us the lowdown on some of the stuff we need to know about these amazing group of animals the molluscs, especially in preparation for summer as we go to the beach and, a bit more about some of these creatures, which have amazing adaptations, to how they operate in the environment. Anyway, I didn't take up too much time I'd like to hand over to Cory. Would you put your hands together to welcome him. Over to you and let us know a bit about you and then kick off.

Corey Whison: Yeah. Great. Thanks. Evening, everyone. And welcome. Yeah. My position is collection manager of the West Australian Museum. So, a lot of people actually ask me, what does that mean? And the best way I can kind of explain it is I'm sort of like a librarian, but with, with animals, sea animals. So, it really is very similar. We go out, we collect, animals, whether we're on boats or diving or walking, we exchange specimens all over the world that people study. We, we identify, images and specimens that people send into us. We're always describing new species. And so, it's a really, busy space and it's a really enjoyable one. But of course, when we're out collecting, we have to be wary of things that, you know, could cause us harm. And that's what I'm going to talk to you about today.

But before I get started on that, I just thought I'd let you know where I work and, and sort of bit more about what I do. So, back in the past, we all actually were based, at the Boola Bardip site, we had a basement with thousands of jars. We had a dry collection. Everything was here, and we had a big, Francis street building. It was about five storeys high where everything was. And then we got moved, because of, an asbestos issue. We got moved to a site out at Welshpool, which is now known as the Collections and Research Centre. So, everything you basically don't see on display, which is, which is a huge percentage, only a small percentage is on display here at Boola Bardip, is all housed at the Collections and Research Centre. So, basically if you go east towards the hills on Orrong Road, and the corner of Leach Highway, I don’t know if you have you been past there, but next time you drive past, you see a red building and big warehouses at the back. And that's kind of where we're all at. And one of our main things is the wet collection. When the new museum was built, we got this huge new 2 storey building at the CRC. At the bottom is our new wet store. And in my area, I look after about, about 200,000 jars of just molluscs. And we'll get to what actually a mollusc is. And we also have a dry collection. And then this is just some of the work we do, we do survey work. And obviously in that laboratory we look more closely at everything. And identify it.

But also, another part of our ole is providing specimens for display. So, I don't know if everyone's seen the Wild Life’ gallery, the sponge display is probably one of our most, beautiful marine exhibits over there. And that's some of those are specimens we've collected. Some are models. But that's another part of our role that we, we do is create stories and provide specimens back to Boola Bardip.

But yeah. So back to what I'm going to talk about today. So, I think it's important to understand why, you know the marine life could be dangerous to us. I mean certainly not something that the animals are adapted to cause us harm. Really. It's, they've developed mechanisms so they can capture prey and feed. So that could be, you know, stinging cells to stun prey. It could be venom to kind of slow animals down so they can feed on them. Equally, they might have, like, mechanisms to protect themselves. That could be spines. So, animals can't get in and attack them. Could be barbs, like a stingray to, to repel predators. And so, it's worth understanding those sorts of things.

The other thing to remember as well is Perth is in what we call the southern temperate waters. So, the water is a when you look at southern West Australia as a whole are much cooler. And that sort of cool body of water extends up to about Shark Bay, and then Shark Bay North, we call it the Indo West Pacific Region, which is a much warmer body of tropical water. And in general, like all the relatives or species that are found in that northern area are much more venomous and much more toxic. So really, when you go on holidays to the north, be it, perhaps Shark bay, but mainly Exmouth, Broome, Darwin, all those places, you have to be quite aware of the animals there, that you might see closely looking like animals you might see around Perth, they're actually much more, generally much more venomous in those northern waters. Around Perth, generally speaking, they're fairly mild. And I'll talk through some of those examples. But yeah, certainly Perth has got lots of habitats where these different animals can, can live the sandy areas and seagrass areas and rocky shorelines. There's limestone reefs that are submerged. Rottnest actually is a really good, environment because it has lots of different habitats as well. So, you certainly can encounter them.

So the first group I'd talk about is the animals that you might, that, that might, that live mainly on the sea floor and you might encounter so on that we call them benthic animals, basically those that live on the floor, the sea floor. And you might come across this or fishing where you might hook something up and that's brought onto a boat. You might be diving or swimming and get to the base of the, the, the sea floor. And so, it's just it's just being aware of these particular animals. And I should say, I do have a lot of these examples, that I'm talking about today represented here, and I think we'll there'll be plenty of time at the end to, come up and touch and feel and ask any questions about them as well. So, some really interesting stuff in here, which I'll, I'll talk about when, when we finish.

So yeah. One good example is, the cobbler or the estuarine catfish. So generally found in estuaries or, shallow coastal waters. And they're pretty much the main area of concern here. These three, I don't know if that's showing up very well is it? But you can see these three, spines there, which if you do happen to tread on them, they can inject, a small amount of venom, not deadly, but can cause extreme, extreme pain. And in some cases, you might have to go to hospital for it.

But the main times people are injured with a cobbler is, because they're most active at night or in early mornings, and quite often they they'll hide amongst sea grass and seaweed. So, when you're launching, retrieving a boat and you're not wearing the correct footwear, that's where a lot of people do, tread on the cobbler and get, injected a little bit of venom. Equally, obviously when people catch them and they handle them incorrectly, they can get, get stung as well.

So, the next group, the Scorpion Fishes. So, these have, this particular one, which you can see has venomous spines, spines on the dorsal side. Just around this area here. And again, they're found in shallow waters, off Perth. But this particular family, is quite a large family. It has about 80 species of stinging, or venomous fish, and about 30 are located off the coast of Perth. And most of these are encountered particularly this species from fishing. So, they're caught, they're brought to the surface, and people aren't wearing gloves and so forth and get stung again, not deadly, but, you know, extremely painful. And this particular family is related to the stonefish. So, in the north, the deadly stonefish, they are of the same family. So that's just an example of like the northern groups being much more sort of venomous than, than what we experience, around Perth. And so, the next group is stingrays, really beautiful animals. It's amazing when you see them. I can remember when I was diving and, so day turned to night as well, because when we dive, we're sort of searching for different animals and molluscs on the seafloor. So, looking down and then this sort of dark area, I thought the sun had sort of left us, but it was a look up and it was a huge stingray. And stingrays can grow up to three meters in length, a couple of meters wide and up to 200kg. So that can be quite, quite, big animals. But really, they're found everywhere, from sort of shallow waters down to 100m of depth, but mostly in sand, where they tend to blend in and feed.

So, but I guess the main thing is to be careful of the barb, which is serrated and venomous. And yeah, sure, it is but it's mainly used for defence from predators. But we all remember unfortunately Steve Irwin who was killed. That was because the barb pierced his heart and he, and he bled out. So, with stingrays is most important to just keep your distance and watch them and try not to touch and handle them and just let them do their thing. So, this is probably one of my coolest examples of a, a potentially dangerous species is the numbfish. So again, very round, flattened animal that lives on the seafloor, can grow up to about 40cm in diameter. So quite, quite large. They're pretty common around Busselton Jetty. It probably more common to the north than the southern areas.

But what's really cool about this particular species is it has a base that acts like a car battery. So, it's a positive and negative, terminal on the ends of its body and, and an organ electric organ that produces a low amperage shock. So basically, if you touch it, you become a conductor and get a low, voltage shock. And they do this to, you know, to stun crabs and fish, so they'll hide in the sand being almost camouflaged. And then when the animals touch it, it knocks them out and they can feed on them because they're such a slow moving, fish that, the ability to shock and paralyse is one of the adaptations to feed.

A colleague at my work said he was diving with another person, and, that the person he was with actually got shocked by the numb fish and actually got knocked out, and he had to carry him to the, to the surface. So, in some instances it can be dangerous, but he was fine, he got to the surface and he recovered. He was fine. But certainly, enough of a jolt to, to knock a person out.

And I've got one of those, I've got a tiny one that I just in here as well. It's pretty cool. Come and have a look after.

Okay. So, sawfish is another. We won't see these around the Perth areas and mainly it’s in the north and tropical areas either the marine freshwater or estuarine. But really cool animals. I've got a rostrum here, just a small one. So, they had these this long toothed extension on their front, which is mainly used for sort of digging in the sediment for feeding, but also for defence as well. And all these particular species in the world, I think there's five species, four are found in northern Australia, and all of them are threatened because of overfishing. So, when other people, fishing for other target species, they are quite often the bycatch that they bring up into the boat. And then there are the sadly killed or discarded, and obviously a lot of people have collected them for the, their rostrum as well as a, as a, as a collectible kind of specimen.

So, yeah, but obviously be careful if you manage to catch one. They are quite sharp as you'll see when you come up. Yeah, they're extremely sharp actually. And yeah. So, a really, special animal. But yeah, you won't, encounter them around Perth.

Yeah, of course. And then there's always sharks. That they are there actually, they are everywhere. Around Perth. I guess we, we just need to understand that it's probably three that, potentially can bite us as humans. There's obviously the great white that you can see there. There's the tiger shark, which is probably more a northern species, but we do encounter it around Perth. And then I guess more recently in recent years, we've become familiar with the bull shark, which I think everyone's probably, I think in general, a lot of people didn't probably know about 5 or 10 years ago, but certainly has caused fatalities. And, just recently there was a quite a big accumulation of them at Fremantle Harbour. I don't know if you so you saw that, that footage. And the bull shark can grow up to about I think it's about four meters. So, it's quite a sizable, we always kind of imagine them to be small, but they, they can be quite sizable.

But yeah, I guess the thing to consider with sharks is, there's a lot more of us , as a population in Perth, technologies larger like we've got all got access to boats and 4 wheel drive, and so, we're getting to a lot of different places and we're probably in the ocean more often. So, have shark numbers increased? We don't know that. But on one hand, you know, our numbers have increased and our probably, interactions have increased. But, you know, if you looked at some, I was looking at some figures from around, back in 2010, in terms of the number shark attacks worldwide, it was something like 79, worldwide. And I think it was 4 or 5, might have maybe six, fatalities worldwide. So, I guess if you put it in perspective, it is relatively low. But there certainly are things that we can do to reduce our, risk, I guess, of a shark attack. Certainly, you know, they are more active at night, early mornings and late at night. So probably restrict, you know, your time in the water if you can around those times. They are, certainly the great white is known to surface attacks. So, if you can reduce, your time on the surface in more open deep water. Spearfishing is a huge risk. So as to something if, you know, obviously you're carrying food in proximity to yourself if you're spearfishing in the water. I'm talking about like scuba divers fishing. So that that's certainly quite a high factor. Yeah. So that is things to, to consider as well. That can reduce the risk.

So back to my group. So, molluscs are the group that I work with, and these are a really cool group, the cone shells. They’re pretty much found everywhere on rocky reefs to sand there in shallow areas. They can go quite deep as well. We've had cone shells from about 4 or 500m. So, but again, what's really interesting with this group and it's not all depending on what they feed on, if they feed on, worms and small animals, the venom will be relatively low. If they feed on fish, which are quite fast moving, they have to have a really high venom to sort of knock the fish out. There’s no point exhausting all that energy into a fish, and then it swims off and its lost, or lost to other predators. So, but basically, they have this, you can see the, the mouth and then they have a proboscis, and out coming out of that is the, this toothed barb which they, they strike into its prey. And that's called the radula. And if you can imagine behind, within the body, it's almost like a quiver with hundreds of these, these darts that they have. And as they inject, they inject the venom into the prey. And there's several ways that can do that. And I've got a few videos which I think will show you at the end because there's a bit of a, it is easier if you watch the three at the end, I think, about how they go about it, it's quite amazing. But there’s, the main, the deadly species are only to the north, so I've got a couple of shells here of those, one is the Geographus cone, and other is Conus victoriae, this is the two that I've got on display here. Around Perth we have 4 or 5, worm feeding species, but they're, very low in terms of their venom. So, if you were to get stung, it would cause some irritability, but certainly not, you know, not in the, the lethal kind of category.

Because they feed on small worms and so forth.

So, yeah. Very interesting. But also, it turns, in a good way, some of the toxins that, the current shells are producing have been used for, manufacturing painkillers. So, they're, yeah, they're starting to, look at the compounds in the venom of, of certain more northern, cone shells. So, this is I'll show you the video. It's just a couple of ways. This is almost like a, an entree to what we'll see a bit later. But there's several ways they can do it.

So, we go to another type of, mollusc. Do you know what class the blue rings in? Anyone know what class of mollusc? Cephalopod. So that's the, that's the class that the octopus are in. I mean, they're still molluscs, but, again, really interesting. So, the thing about the, the blue ring is that they're more common in shallow areas, sheltered areas and rocky areas. And they, because they've got no shell like a mollusc, which generally has a shell. The cephalopods don't. And so, they that look at other ways of protecting themselves. So generally speaking, the blue ring likes to hide in small objects, be it shells or even in debris like cans and things like that. So, yeah, that's kind of one of their, I guess, main kind of hideouts. But the thing about them, they're beautiful, bright, iridescent rings, you won't normally see that, they only produce that when they're, aggravated or they feel threatened. So, yeah, you generally won't see that, but it's really beautiful iridescent, coloration and how they, actually cause harm is on the underside of them they have like, a, almost like a parrots beak, which is their mouth. And near their salivary gland is where the venom is held. So, when they by the saliva goes into your, blood stream. And that's when the venom's released with their saliva into the blood stream. So, if you have a look at the two images you see there on the left is small. The ones around Perth and the southern cooler are generally much smaller like the animals are, and I've got a couple here that you can have a look at in the jar afterwards. And the one on the right is a much larger species, which is more northern. They're considerably different size. Like if you, you know, you've got my hand sort of that size and, and so the, the blue rings around Perth, like that's kind of the difference.

And yeah, certainly there's, I think there's two fatalities from the blue ring in Australia, one from Darwin and one from Sydney. Oh, from the northern, larger blue ring, again because it has a greater degree of venom. But really cool, there's lots there's still many unnamed species of blue rings. We have so much to learn more about this particular group. And another interesting type of, of mollusc is, a bivalve or the razor clam. So, you know, bivalves have two valves and have the animal inside that creates the, creates the shell. These particular animals, tend to like sandy or muddy areas, and they'll attach to, through like a rope like substance, to anything in the in the sediment, be it shells or a bit of coral or whatever. But they'll tend to, bury into the, into the mud and just have the very top showing, which is razor sharp. And so, what they do is they filter the water in the environment to feed on the microscopic, plants and animals. But yeah, if you're out walking in the areas. They're not so common here. They're a little bit more common in South Australia. Albany and up around Dampier and some areas there. And so, if you walk out and you've got no, not the correct footwear, you can get a nasty cut which can then become, infected. And I've got a big one there from the north, that you're welcome to have a look in a minute. They get quite large. That one's probably about so in height, but yeah, it'll bury right down to the very, the very tip will be only exposed.

And another type of mollusc which is a type of sea slug or nudibranch. Is the giant sea hare. So, this is really interesting. So, these animals, are quite large. I think I get to about that kind of size. And basically, they become harmful because they feed on an algae that contains a toxin, and then they, they can reuse that toxin. So how they do that is, one, they have a purple toxic, toxic dye that they'll release when they're threatened, if something external attacked them. But unfortunately, that is harmful to, a little bit to humans, but more so to dogs and pets. What basically happens is they only live about a year, so they'll, they'll reproduce after about a year, and then they die in the summer, usually about February or March, and then they wash up in. I don't know if anyone’s seen them? On the beach? Rockingham, Cockburn it's quite a common area for them to, to wash up, but probably other areas as well. And yeah, just make sure that, you know, if you're walking your pet, your dog or whatever, just make sure they don't, go and bite and lick the aplysia because, yeah, that, that that has caused a few deaths as well.

Actually, we used to get a lot of calls. They used to be an abattoir nearby at Cockburn, and we'd get a lot of calls, saying that they have discarded the, the animal parts from the abattoir, but it wasn't. It was these, the sea hares had just had a massive kill, which they do every year. It's a natural event. But yeah, just be aware if you were walking your dogs as well.

And of course, that beautiful sea slug. So, a similar example, but it's just to show you that, again, a lot of nudibranchs, or sea slugs, feed on sponges, for example, that contain toxins. I've got a couple of sponges here that you can have a look at as well. But this is purely for defence. And, and basically the bright colours are a signal to predators that I'm not palatable. You know, if you'll get sick if you, you eat me. So, Yeah, it's kind of, it's an interesting relationship. They're feeding on the sponge. Sponge has got a toxin there that's beneficial to the sea slug and so on and so forth. But yeah, to humans probably we would get sick if you were to consume them.

Just another, type of cephalopod actually, this is a cute one of my favourites, actually: The pyjama squid. Has anyone seen the pyjama squid before? They're really cool. I actually, one of my first field trips was to Shark Bay. We were just talking about this before, I think 2002, and we were trawling the sea floor and they, they typically like sand and seagrass, relatively shallow, areas that they feed on. And, we were pulling these particular pyjama squids up and just an amazing to see the patterning. Really not probably that dangerous as such, but they can produce a bit of a toxic slime to coat them. So, you probably want to handle them with, with gloves. They are usually out at night to hunt. But yeah, they're actually a type of cuttlefish.

They're not really a squid. They're actually more of a type of cuttlefish. But yeah, really beautiful. And yeah, I think they're about it's about that kind of length from memory.

Yeah. So sponges. So we, we have, at my work, so we have myself and, Lisa who work in molluscs. We have Anya and Andrew who work in crustaceans. I've got a big mangrove claw there that they provided for us to look. We have the fish people, which are Glenn and Jenelle, and they’ve provided some sharks and some other specimens. And then we have, Oliver, at the moment is the only one in sponges. So he's probably one of the few kind-of sponge experts really in Australia. There's only a handful really. And that's probably the case for all of our groups. There's not lots of people everywhere that know what certain things are. It's not, like, there's, you know, taxonomists growing on trees. It's really quite a limited, area, particularly sponges. But so, there's so much work to do with sponges.

But again, they're found everywhere, particularly in the North. They can give you some reactions from the toxin. So, when we're in the field, we always wear gloves. When we handle sponges. One for the toxins, but also a lot of the, a lot of sponges have these glass-like spicules, that is the compounds that make the sponge. And they can sort of, embed and you get like glass splinters basically. So yeah, pretty much always wear gloves with those ones. Very interesting. There's a lot of diversity, a lot of big ones that we've collected in the deep sea as well. Hydroid. So, this is the phylum Cnidaria. So, these are another, very similar to anemones, and sea jellies, in the way that they operate. But basically, yeah, they had stinging cells and nematocysts that, will fire upon touching. And yeah, certainly you can develop a rash if you're struck by some of these stinging cells, much like in the way of a, jellyfish, that you, you might get in the Perth waters.

Anemones are really cool. Have many people seen a sea anemone? Yeah, they're really they're really awesome. So actually, the first time I encountered anemones with work is actually they harbour a, a really cool type of gastropod called a Epitoniid . This is beautiful, spiralling gastropod with beautiful sculpture, and if you kind of prod the anemone, it will retract in, and that's the time you can actually see this because they have a relationship and you can collect these and sort of different species are host with particular types of anemone. So, there's a, there's a relationship there, but again, they have the stinging cells as well on the tentacles. And yeah, it can certainly cause a lot of pain. Even around Perth with this particular group as well. And hydroids.

Of course. Sea urchins. I just find these really, really creepy looking things, the, urchins. But again, they have these long-pointed spines. Some of them do, some are quite short, and they found usually they'd like to wedge into to rocky crevices as well. Is a pretty common place for them. But again, yeah, the northern ones, are venomous, the southern species not venomous, but equally, you know, treading on them or getting spiked by them. You can get sort of badly infected from one. They tend to break off when you get pierced by them, and they create a real infection issue. I think we had a, one of our science team working up in the Kimberley, West Kimberley, in the last year. And she, had a spine break off and it got a little bit infected as well. So yeah, it's just one of those things we have to be careful with. She was actually collecting them as well, so it was part of trying to collect them and bringing them back to the museum. They're very hard things to, to store, as you can imagine, because we have, we have limited glassware. So, these things are yeah, obviously quite, quite wide in diameter.

So, yeah, the other group that we have to think about, pelagic animals are those that are floating in the, in the water column and that we might encounter, again, probably through swimming, scuba diving, or mainly, probably those that wash up on the beach. Be it probably in winter, around Perth where we have, like, strong south-westerly winds and swells that push these animals, which are really just sort of, floating in the, the ocean and just driven by the currents. So, when the winds and the swell are pushing it to the shoreline, that's when we tend to encounter them. So yeah, we've got the blue bottle. Again, as I said, they float in warm currents in open ocean. And when the conditions are right, they will wash ashore. And the top part, the float, the flotation or the, the chamber, that's not, that doesn't hold any stinging cells. It's the tentacular section below that holds the nematocysts that, that, that can sting. And so, it's we certainly can get, some pain and raised mark and, and the nematocysts do persist a while even when they wash up. So that's something to be careful about. Even if it's washed up and looks kind of, yeah, long dead. They certainly can still fire.

And. Yeah. Then there's the box jellyfish. Did everyone know they're now called sea jellies? You guys know that? Because everyone, it was argued that they're not fish anymore. So, it was confusing. So, we call them sea jellies. I’m trying to think of the other one. What's the other thing that was fish that has been changed, Starfish, that's the one. Does anyone know what a starfish would be called? Sea star. Yeah, that's what they're called now. Yeah, yeah. So, we refer to them as both. But yeah, the fish people go ‘no, no they’re not fish’.

So, yeah. Anyway, so the box jellyfish here's a really good example. So, the southern, jingle on the left, is not, not deadly. It's certainly, you know, cause a sting or whatever, but. Yeah, on the on the right is the deadly northern box jellyfish. And that is one of the most, venomous, animals in the world. Yeah, it's certainly, very dangerous. And it usually, the blooms, it's called the stinging season is usually in the summer. So, from about October to March in the northern tropical areas, and you have to take a lot of care in those areas. You'll see a lot of people with the stinging suits, when they swim and, yeah. But so our particular, southern box will probably wash in summer, usually when, you know, conditions are quite, into sheltered areas, when conditions are, quite still. See them a lot in Geographic Bay and Woodman's Point area. What’s the bay around Woodman’s point? Cockburn Sounds. I am having a moment. Yeah, so, in those particular areas. Like those areas, like very still areas, they wash in and just sort of settle there. And. Yeah. Sea snakes. Sea snakes are really cool. Has anyone encountered sea snakes when swimming. Yeah. So, I hadn't seen a sea snake, at all until I dived with the museum. They are more common, as it says there in the tropical areas, and particularly offshore areas, as well. So, but there is a southern Australian species, the yellow-bellied sea snake. But, yeah, these things drift on the surface of warm currents. They can wash ashore, and they can survive out of water for a little while. And the thing about them is they are very, very venomous, but the structure their teeth is that they can only inject the small amount of venom. So usually, I don't think there's been any, fatal encounters from what I can understand, but, yeah, it's usually a structure of their fangs that it doesn't allow them to take a deep bite and inject.

But, yeah. So, I was swimming. We're at a place called Rowley Shoals, which is like the offshore islands. It might have been at Scott Reef, actually. I hadn’t encountered them, and I ducked down and, I looked out in the water, and I would have seen about 100, I reckon, just dangling from the water like little ropes just dangling and some on the seafloor. And as soon as they saw me, they just made their way towards me. But they were just curious. They, like, swim around me. I was like a little bit freaked out at the start. And then you just relax. And they were just, like, licking my, glasses. And I look over and my colleague, who I'm diving with, he's just like, rubbing the back, which you should never touch, such rubbing the back of the snakes. And they're actually really friendly and curious. And once I sort of seen who we were and what we were doing, they were just straight back down and we'd dive. I think we did about 5 or 10 dives in that, that area and not one problem. Yeah. So, I think that's just the story, just let them do what they need to do. And, they'll be fine.

And yeah, of course, sea lions, which, you know, we all we probably see these and we think they are beautiful creatures. But of course they do, and they can bite, their teeth are full of bacteria. So, if you do get bitten, it can be a nasty infection. The males are particularly aggressive during breeding season. And the mothers, particularly if they've got pups, can be a little bit aggressive as well. So, it's just worthwhile knowing that if they're around in that particular time, just take a bit of care as well.

Yeah. So, I think that's sort of coming to the end of, my talk, but I just wanted to basically recap like what I was talking about. So, the main thing is, yeah, not to be, alarmed about the marine environment. Most of the time, you know, the mechanisms are, because, you know, sea life is, they have to obtain food. So, they've got these mechanisms to capture that food. They might have, they, they've got mechanisms to stop, them being attacked. So, for, to repel predators. And a lot of the time, a lot of the incidents we have is through accidental interaction or we, we were aggressive towards the animals. So, a lot of the times we've had with like the cone shell bites and the blue ring, is people collecting shells and putting them in their pockets and remembering, not knowing that there's an animal inside. And this animal's now in complete darkness, in a dry environment, and it's just reaching out at whatever it can, you know, it's freaking out, and they can just sort of jab something. So, that's one of the main times it tends to happen. If you're kind of enjoying the natural life, marine life and just watching them go about their thing and don't touch, that's always, a really good way to, to approach these things.

And yeah, I guess we are lucky that we don't, you know, we're not in those northern tropical areas where things are a lot more, venomous and a lot more toxic. Generally, around Perth, with a lot of the examples I've shown you that's on the very much the low level of, of venom, and so, you know, it rarely is kind of fatal.

And yeah, we shouldn't forget that a lot of things are being, investigated and manufactured to help us as humans. So, I mentioned the cone shells. There's a lot of work being done on the compounds in sponges. There's a whole. Oliver, who works in the sponge area, there's a whole bio prospecting collection that that he looks after where they're working through, trying to see what different compounds can be used in medicinal purposes. And, I think there's a, there's a real strong belief that, yeah, there will be some really exciting finds as we discover new species, as we go to new, different places, particularly deeper water, we turn up species that might have compounds. And, yeah, it's a really exciting time.

So, yeah, I'd like to say, thanks for coming tonight.

Audience Questions:

Audience Member: What happens to the little spines in the cone shells once they have used them all. Do they, like, re-grow some or is.

Corey Whison: Yeah, they're always. So, they're always manufacturing them. So, if you imagine, a snail, sometimes in some species, it's presented as like a tongue with lots of little, lots of little ribs, sort of teeth on them, that graze on things. In the cone shell they've actually modified that so that each of those little teeth is one of those barbs that you saw. So, it's constantly producing, it's infinite. Yeah. They'll never they'll never run out. Yeah. Just manufacturing and expelling from there.

Arlene Moncrieff: Just a bit like sharks to keep coming forward? They just keep producing them that way? Corey Whison: Yeah. And you can imagine like. Yeah, call it like a quiver and an arrow, you know, like it's just. Yeah, it's, it's, it's continual. So, but yeah, those ones that are really deadly are kind of, piscivorous I think it is. Okay. It is, the ones that are targeting, fish mainly that are, that need to strike them down. So, they, they're really like, on the high level of venom.

Audience Member: What are some of your responsibilities in the wet specimen stores? And also, off the top of your head, do you know what the oldest specimen would be in the collection?

Corey Whison: Yeah, there's some good questions. I did know this, I think in my collection, well, in our collection in molluscs, I think it was. I think was 1878. It was, a land snail collected from south of Perth. I think that's about right. It will be a couple of years off. Off with that. And. Yeah, the wet store is, there's, there's a whole number of tasks, I guess, but the main one is everything's in ethanol with specimens in it. So, there's a constant battle to make sure that they are housed correctly, and ethanol is full, and specimens well looked after. So that's kind of an ongoing task. But really, one of the main tasks in recent years is. There's a lot of material, so, everything that we have in the collection, we enter into a database. Has anyone used A.L.A in the Atlas of Living Australia? It's basically where all our data will end up. So, if you want to search an area and look for molluscs, or fish, or crustaceans or just molluscs, or you want to look and see what records of particular species are, you go to the Atlas of Living Australia. It's a really easy to use website and it's got all museum data there and I think they also incorporate, ‘iNaturalist’, you know, the, it's where, it's another platform where people can record sightings, but all that data goes up to A.L.A. So, but only a small fraction of what's in our, collection is actually digitized, so it's a real push for us to, get a lot of that information, and that's going to take a long, long time to get that onto a computer and uploaded. So that's, that's a, that's another sort of part with the wet collection that we try and do. The wet collections always, is also, become really, I guess, popular in recent years because of DNA. So before, you know, you look at a couple of specimens and you try and compare their morphology: why does that one look different from that one. Which we still do. But now if it is a fresh specimen, we'll take a bit of tissue and we'll get it DNA sequence. And it gives us also another an answer as well as to, you know, whether these things might be the same or different. So, there's a lot of use of our collection at the moment for, for DNA. So, taking from all around the world and different projects that people want to sort of get tissue and, and sort of work out from a, from a DNA perspective, where the animal sits.

So, yeah, hopefully that's answered some of your questions. Yeah.

It's very big. Like, I, I work I think we've got about 150,000 jars, maybe 200,000 now. And I think we probably only got about, about maybe 20, to 30,000 on computer or something like that. Yeah.

Audience Member: What's the theory about why warmer tropical waters have a higher incidence of venomous critters as opposed to cooler. Corey Whison: Yeah, I think it's, it would probably because of, the busyness of the tropical waters. So, I think, like, the really high tides that you get in, and the, the movement of nutrients and the warmer waters, things that it's faster in warmer waters. So, I think the idea would be that, you know, everything's happening a lot faster. It's a lot busier, a lot more in some ways diverse as opposed to here where there's it's probably slightly less diverse and, being cooler with not much water moving in a nutrient kind of exchange. It's sort of slower, I guess that's kind of, there's no. I don't know of the, you know, the complete answer, but that's what I, I assume it would be, you know, because of the, I guess, the ferociousness and the, the busyness of the tropical environment with all those, the water movement, some ways of, the, the more diverse marine life that, yeah, things of things have to be sort of cease, like stopping their prey very quickly because you've got lots of different predators as well. Whereas in the cooler environments it's probably a lot, a lot slower. The activity. Yeah.

Audience Member: KI am wondering with the old. Are a lot of the species and becoming extinct or at a, at a what sort of rate are new ones coming along?

Corey Whison: That's a really hard one to answer because, I would I'd say, first of all, we're, we're regularly discovering new species. But there's a number of new species in our collection already, as well. So, the value of what we have in extinctions probably won't be known until, more will be better known to the point in the future. So, all the specimens we have now that are in the collection, at a point we'll probably know more, but I think we're still at a point of understanding what we, we have. So, yeah, all these collections are actually really important because we can, we can document that, that they existed. So probably, it's probably more noticeable in the terrestrial environment where, we can sort of see the change more visually, like, you know, forests are gone. And in those areas are gone, we've got collections from those places. In the marine environment it's a little bit, a little bit harder at the moment, I suppose. But yeah, I don't really have an answer on the things that are extinct because we're still beginning to understand what we have. And that's, that's still very much ongoing. But, I think, yeah, once we once we get a really good understanding, then those collections and those dates and those times and places will be really important to work back and say ‘well these animals were here at this time’.

We do at the moment for things like, like marine pests that, that in the marine we can trace back where, you know, and introduced oysters or each introduced mussel is coming to, the Perth waters. And sometimes we can go back to our collections and see when it was first recorded through a specimen and then may and sort of extrapolate that it might it came with the, you know, this particular voyage or, you know, something like that. So yeah, it's quite important in that regard. Yeah.

Arlene Moncrieff: And we've talked, or you've talked about, not me, aquatic environments, but there's also some projects that you work on around land snails too, isn’t there?

Corey Whison: I do. Yes. Yeah.

Arlene Moncrieff: Can you, can you tell us a bit more about the citizen science one in particular?

Corey Whison: Yeah. So, I work in molluscs like across, I've talked about marine, but they're freshwater as well, and then they’re terrestrial. So, we actually have a really diverse land snail species in Western Australia. So, most people would think about, you know, land snails being introduced in their garden. You know, you squash them and throw them in your bin. But no, we actually have, both north and south, really interesting and, very old species of land snails. So, one group I work on is called Bothriembryon and so, they've found mainly in the Southwest. And so, we, we realize we couldn't, get out and, because with land snails, if it's hot they'll perish so they only come out in winter. So, this is like a short window that they'll come out when it rains, they need moisture to kind of move around. They bury otherwise. And so, WA is huge and it's a very narrow timeline. So, we developed this, the citizen science program called ‘Snail Snap’. And so, we ask people when they're out and about, I've mentioned iNaturalist there's an app called iNaturalist, which you can record all different flora and fauna, I think it is flora as well. But yeah, just basically we ask people to take a photo of what we think is this particular snail when they’re, generally probably out in, quite sort of native, healthy kind of woodlands or forests or whatever. And yeah, then we get on, we identify the animal and, we keep a record for ourselves and yeah. It's been really successful in like, finding new species for us and, sort of confirming things are still there that we thought might be extinct. So that's an example. So, yeah, it's really, really been really popular app and next year will be our 5th year. Yeah. So, we're trying to yeah, we're trying to kind of guide people to yeah, really get on board and, and help with that, that particular citizen science project.

Arlene Moncrieff: And that's usually in July, I think.

Corey Whison: Is that like June. July. Yeah. June. July. August. Yeah. Yep, yep. So.

Thanks for listening to the talks archive brought to you by the Western Australian Museum Boulevard. And to listen to other episodes go to visit Doc Museum WA doc after you forward slash episodes, forward slash conversation where you can hear a range of talks and conversations. The talks archive is recorded on what Jack butcher, the Western Australian Museum, acknowledges and respects the traditional owners of their ancestral lands, waters and skies.

More Episodes

Join Dr Laura Skates to discover how these amazing plants capture and digest their prey and hear stories of the fascinating history of carnivorous plants.

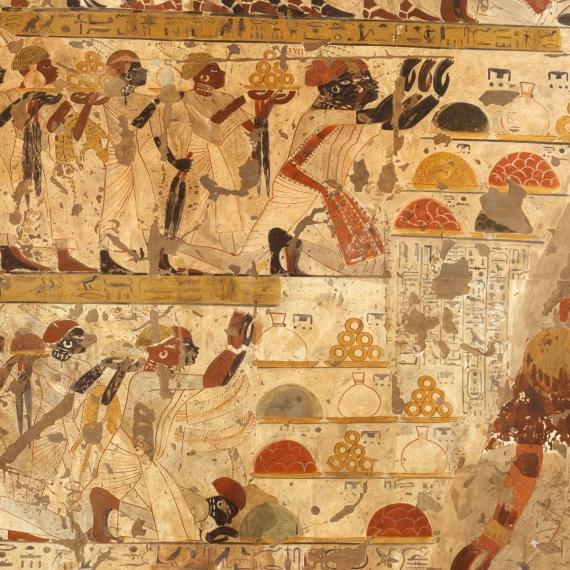

Visiting Egyptologist, Nubiologist and archaeologist Dr Julien Cooper of Macquarie University shares insights into the workings of Egypt’s gold industry, drawing on ancient texts and new archaeological surveys in eastern Sudan.

Join Bryn Funnekotter, a biotechnologist at Kings Park Science, as he shares how and why we are helping conserve some of WA’s most endangered native plant species.

Join the WA Museum Boola Bardip Learning & Engagement team for an exclusive behind-the-scenes look at how we create unforgettable experiences!

Join leading barrister and former President of the National Native Title Tribunal, Raelene Webb KC to explore the connection between art and law in the Spinifex People's pursuit of native title recognition.

Join Erica Boyne, head of History at the Western Australian Museum's Collection and Research team, as she reveals the detective work happening behind the scenes to uncover the intriguing stories behind the objects you see on display.