A curator’s dilemma!

Do you know a sycamore box, an alabaster ointment jar and mummified objects were part of the first ancient Egyptian objects that came into the Museum back in 1897?

Dr Moya Smith Curator, Anthropology & Archaeology, discusses these objects in detail along with other items from the collection. Hear about the first Director of the Western Australian Museum and Art Gallery, Bernard Woodward and how he collected these objects and the legacy they leave curators.

Learn the fascinating process of how curators accurately identify items and trace their provenance which can sometimes be very complex when objects arrive.

-

Episode transcript

Moya Smith: Thank you. Thank you very much. Now, this is because I singularly failed to give Sarah a bio, having promised her I would write something, but I think you've captured it very nicely. [I’ve worked a] long time at the Museum, working with Aboriginal communities, working on the world cultures collections, and getting to play with the Egyptian collection for forty years.

So, when I started as a very, very, very green assistant curator decades ago, I had no idea that the WA Museum had Egyptian objects at all. So, I was out in the collection area, hunting for beads, and suddenly there's shelves like this. I saw a little paper, pieces of paper saying ‘Egypt’. I thought, Egypt? What is Egypt? What does this mean? So, pulling one open, I found this glorious Predynastic pot. I thought, this is so exciting. I must admit— That star that's up there that you can sort of see, this is the old Francis Street building where I used to work before they pulled it down. In the centre of that sort of block of offices which were around the corner when my office was there, fourth floor, were the collections.

So, floors two, three and four had the collections. All the science collections. All the history, anthropology, archaeology collections. Maritime history has always been down in Freo [Fremantle]. That's what we found.

So, I raced back to the office and said, “Oh my God, nobody told me. Nobody told me we had Egyptian material.”

They said, “Well, it's actually one of the reasons we hired you, because you're one of the few candidates that had anthropology and archaeology, you’d worked with community, and you've also got this Middle Eastern background.”

At that stage, they didn't know that I'd left the Middle East because someone had pulled a rifle at my chest and said, “Why are you fraternising with the enemy?” But still, that led me back to Australia and Australian archaeology. And forty years of trying to make sense of this collection.

So why do we have this? Why do we have this stuff at all? We can thank Bernard Woodward, who was the first Director of the Museum and Art Gallery. From 1889 he'd been the curator of the geological museum, and then on to Perth museum, and then finally the combined museum and art gallery of Western Australia.

He had astounding family connections. He was English. He came from people who had been connected with geological collections in England, and other collections as well, which inspired his interest in the idea of objects and the idea of sort of ownership. Also, the idea of trade and exchange. He was also passionate about the arts; it was because of this he was pursuing— What he wanted to do is build collections that would inspire the fledgling—not so fledgling colony—but inspire the colony, inspire artists, and give people a sense of all the amazing creativity that characterised the world. And so, thanks to Bernard Woodward, we do actually have some Egyptian material.

So, this is his family network. Starting at the bottom with his grandfather down there: Samuel Woodward. And then onto his father, who was Professor of Geology at the Royal Agricultural Society. His uncle looked after the art collection, the library and art collections at Windsor Castle. So, they're well connected. And then on to himself and his brothers and cousin. They're all deeply involved in the idea of collections and organisation. The only problem with all this for Bernard and for the Western Australian Museum [was] that he was pretty much it, in the early days of the building up of the collection. So, he was both curator, director, registrar...

Finally, in about 1912, he seems to have hired one of his nieces, Ms. Bayfield, who went on to, I think, actually register quite a few objects. So, in this gap we have the beginning of problems.

So, what do we have? How do we know what we've got? We rely on record keeping. I cannot harp strongly enough about this. Record keeping is the essence of what you must do if you have collections.

If you're an archaeologist working in the field, if you're a museum staffer, keep very good records and register objects. And by register, I mean put something that is an identifier on them. So— But the Bible for us is this beautiful old—and the Egyptian collection—is this beautiful old Arts and Crafts register from the early days of the Museum. We then have day books that were filled in first, when material came in, a list was put in the day book. So, things were given a number. The number didn't necessarily end up with any attachment physically to the object.

Then in 1912, Ms. Bayfield started— I think it's her. We’ve decided we needed to just find letters and see if we can identify writing. This is a conversation at about 3 o’clock this afternoon with two other staff members. We need to track their writing.

So, she started the actual list in the register, which we still keep going, we still refer to. And we still—despite what the history department says as advocates for the digital world—we still keep a written record as well as digital records. So, in the 1970s Jeanne D'Espeissis/Jeanne Hohnen, did the first real audit of our collections, and that was done with card files, a card file index system. <laughs>

This is before we had computers. I was thinking how quickly I've forgotten how horrible it was to not have a database that you could just flick to and recall things. But, of course, there are missing links, as I said, between the records and the objects, so really it is ‘bring on the database,’ which regrettably also has problems.

So, not having numbers, not having information didn't stop everything being put on display and being interpreted. So, this is one of the early, the earliest image I can find of an exhibition of the Museum's Egyptian collection. I think it went on in 1962, 1963, but quite a few of these things, there's no data.

Okay, so I'm looking at the very first collection, going to focus on the very first collection of objects that we know of Egyptian artefacts that came into the collection in 1897. And some of them still don't have adequate data. So that's not bad after one hundred years. It was my goal. It was my goal to get it all done.

So, the red ones that have the star, they are problematic; the yellow ones are things that have been identified, of the group of things that came from our earliest collection. And two at the top, which are pieces of cartonnage. So, all up, I think we've got about three hundred and fifty objects.

As I was explaining to someone earlier, I finally lost the plot about 1995 and decided I was sick of all these objects without any numbers on them, so I gave unnumbered things a new suite of numbers written into our newest register. But in the last month, as I've—more than a month, in the last years—I've tried to bring order back to the Egyptian collection, I realise it's now a bit unclear what objects did have an original tracking number, did have an Arts and Crafts number, and didn’t. So, I'm just I'm trying to collate those. My goal before I retire is to have the electronic publication, the e-book of the Museum's Egyptian collection that everyone can refer to, that will be faintly accurate.

So, in 1897, listed in 1897 by Ms. Bayfield, we think— But clearly registered after 1897 because, above it, the first numbers in that sequence before 18, the first numbers relate to a man called William Leonard [Stevenson] Loat, who was also working in Egypt, near Abydos, and who in 1912 had donated a group of objects that he’d clearly purchased in the Abydos area. So, they take up the original sort of 16 or 17 numbers. So, we know they came in in 1912. So, we've got them registered before the 1897 material. So, it's like, well, this is clearly a recipe for chaos. They do have day book numbers. Most of these things have day book numbers.

Now, you can see with the stars— I found a typed list of objects from 1963 and a lot of things are listed as, “there is no data for these.” And this included the three portions of sarcophagus from Thebes. All this material that T. S. Henry gave us, sold to us for £10, all this material was said to have been collected in Thebes.

So, three portions of sarcophagus; two mummy heads, one male and female; two feet; a mummy hawk; two mummy snakes, one in a box; portions of cloth mummy wrappings; a sycamore box containing floral wreath; and alabaster ointment jars.

And up in the left-hand column, you might or might not be able to read the bit where he says, there she's written, “also one stone image,” which didn't have a number at all, ever, until 1995. So, we do know which of the portions of mummy cloth might be wrappings as there’s absolutely nothing else they could possibly be. And we do know what is this little stone image, which is the top of a canopic jar. So, then I registered— They’re now safely, safely sort of trackable and relatable to T. S. Henry.

The only things that aren't in any way closely and easily and convincingly related to T. S. Henry from 1897, the first of our objects in the collection, remain the portions of the sarcophagus from Thebes. Whether they all were made and acquired in Thebes, of course, is another question. I'll get onto that in a sec.

So, I think I said earlier, one very, very vital element in collections in museums or in the field is some way of IDing what you've got. And the way of doing this— And ideally everything will have a unique identifier, a number, something that makes it the only thing it could possibly be. But it might not be just one object, it might be groups of objects. Groups of objects from a particular tomb might have the same number, but at least they're then relatable. So, this allows us to associate items with their find location, with other associated materials, with dated materials, and to reconstruct the narratives. So, the biography of the object, which we're all very fond of talking about as anthropologists. The life story of the objects and how we got them, how they got there, what they mean.

So, these two highlight this really well. I mean, the irony of the one on the left, of course, is that until 2005 that had been, that whole collection of material from Abydos, had been attributed to the wrong collector. <laughs> So, I'd spent years before that thinking, look, I just can't make sense of this. You know, this is meant to be John Garstang.

Because the other cautionary tale is that we all have the most trusting faith in the infallibility of our registers, and while we still say this and we still think they're the best thing since sliced bread and they're not likely to have the same sort of errors that our databases can have... yeah, there's still problems. And that was an absolute clanger.

So, I looked at books written by other people about the same site and thought, look, I just, these pots look so like this. I just wish I could make sense of where Garstang was and what he was doing and what happened to his records. Maybe they were bombed during World War Two, because he was in Liverpool. And then one day Janet Richards from Michigan museum was standing there talking to me and I said, “Look, I just hate this. I just can't work this out.”

She said, “Well, that's because they don't just look like the ones in the book. They are the ones in the book.”

I thought, oh... Whimper. So, they had been collected by Loat. In the back of these publications— This is ‘Abydos, volume II,’ I think that these occur in— ‘The cemeteries of Abydos, volume II, 1912,’ because they're very rapidly getting their stuff out there— [publishing very rapidly].

There's a list of places that material was sent to. Regrettably, they didn't list the Western Australian Museum despite the fact that we did receive material. We, in fact, got two groups of material from Loat at about the same time.

One was a series of pottery that he had excavated with Eric Peet from some of the cemeteries of Abydos; cemeteries D, W, S, R, and another one that I've forgotten. And the other group of materials is stuff that we’ve— I found a letter subsequently that said he’d bought this. He had bought this stuff. Another group of materials in Abydos.

So, the first group was part of the classic system of, excavators were allowed to take a percentage of material that they excavated. Theoretically, the Egyptian authorities would decide first what they wanted to keep and then the rest could go. Whether that was how it worked in practice or not, I'm not entirely sure.

But the Egypt explorations fund those excavation committees. People relied on being able to sell material or trade material to keep their excavations running. So, they're not in big institutions with oodles of money that could keep you operating forever, and no system of grant getting, so instead of grant getting it's the commercialisation of your excavated materials.

The best thing about this is we'll be able to join with other museums in Australia to say what exactly we've got and we will, um— And, you know, well, Egypt knows what we've got because I've told the people at the Cairo museum endlessly.

The really cool thing about this, I thought, well, okay, now I'm going to start on this. I'll sort all this stuff out. So, I'll start with Loat. This will be a nice little paper for Africa and Australia. I thought, well, from the S cemetery there are only two— Which is quite— I don't know how many of you know Abydos. There’s a big— The main thing that's led the Europeans out into the desert is really the shuneh, the cult enclosure of Khasekhemwy, one of the early dynastic pharaohs.

So, cemetery S is more or less in front of that, in some unmapped band, as far as many were concerned. Loat, in fact, had mapped it. This is the only object we have that I thought, oh dear, this is a simple object. I really like cylinder jars. The other one was a much later jar and didn't look very interesting. This one turns out to be, it’s Old Kingdom. But not only that, when we finally mapped it, and I very closely read Loat's reports, and Petrie's reports, because he went back to excavate the site too. I realised that this particular pot could be mapped exactly on the ground. I mean, you can pick it out. I can now pick it out in Google Earth. It's underground. You can't see it.

So, it was from a subsidiary burial of what Petrie's used to call the courtiers, around a cult enclosure of the third or fourth—I've forgotten—third or fourth Pharaoh of the First Dynasty, Djet. And the person was buried with “a lot of cylindrical jars” and series of pottery drawn. So, all the pottery, the cylinder jars, are drawn in the publication.

As well as that, there is a description of the burial, the tomb itself, and the fact that there was also a model granary in there. So, the suggestion was that perhaps this person was a granary overseer—or, perhaps just liked grain and beer. Who knows?

So that was— I was so excited. So, it had been transformed. It was just the beginning of the transformation of a collection and it's such a buzz to finally get there. But also, because he’d registered it! <laughs> You could see where I was going, can’t you? As had Garstang with his collections from Esna. Nice number. 30-E. Absolutely still mapped. We can find that in the universe. We might not— Well, we can find where it was in the universe. We might not be able to track where all the objects have gone to in the world, but we can certainly track it.

Now, I am heavily dependent on the kindness of others. That makes me sound like a Tennessee Williams character. But people have shared photographs with me, shared information with me, done drawings for me. Chris Bryant tried to track things for me. Jasmine Day. I am so, so grateful to all the people who have helped over the last forty years. I just hope eventually in the next year that I manage to do justice to all your efforts.

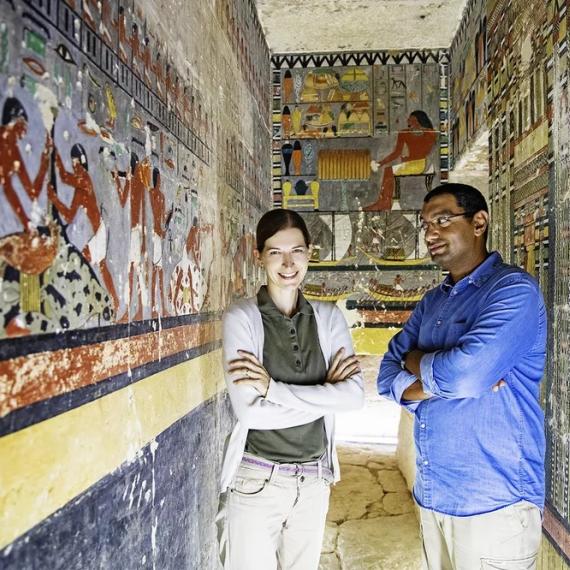

So, Heather Tunmore, one of our honorary associates, has sent me a whole bunch of photographs to demonstrate the amazing best practice of digging at an Old Kingdom tomb in Abydos. So, it's painful numbering of everything. And I think if you look at that site, that photo on the bottom right, which could closely mimic some of the photos that Loat had taken, or Petri had taken in the early 1900s, it is the same sort of massive scale of archaeology. As an Australian working in Australia, as someone said, “All your sites you dig, like, telegraph boxes, telephone boxes. You're in a meter square.”

I thought, yeah, I can imagine a metre square in a site like this. It would be transcendent, wouldn't it? So, each zone is mapped off so that it's given a specific number. People are laboriously writing things in notebooks, sometimes using iPads. But basically keeping, constantly record keeping and constantly updating it, and knowing where everything you've got is coming out of. So, moving stuff away, they're both sieving at, then numbering it, putting things in plastic bags.

<laughs> So if you felt daunted before, <laughs> here you go. A season. Each of the buckets is labelled from a particular zone and then will be sorted in these sort of sorting fields in front with trays for specific, ah, particularly good finds.

She thought people might like to see what beaded nets actually look like in the field, because I think there's that sense that things still retain their beautiful shape. But no, they don't. Look, this is what beaded nets look like, and— Beautifully labelled. I was most impressed. Particular types of plastic and particular types of pens that don't rub off when you write on them. Usually little tags inside the bag as well. And then re-numbered, re-bagged, re-sorted, notes verified, and database updated back in the office— Back in the dig house, not so much an office.

So, conservation in the field. Again, Heather’s in the process of conservation in the field of re-bagging some of the tiny, small finds. She'd been looking at plaster from one of the, that had fallen off one of the painted walls in the tomb.

And then of course, you know, we're not totally without— We're totally not totally pen and paper. So, from ground, from particular, the wonders of contemporary science where you can actually pinpoint exactly where you are in the universe. And then— But still, and this is from a shot I nicked from the Saqqara [Rijksmuseum van Oudheden] website from their dig diary for early 2023, where they’re actually, it's back to the field notebook. Sometimes it's easier. It's important to actually describe what you're seeing in the field as well as keeping your detailed records and your photographs, because sometimes your field notes make more sense of what you're seeing than the actual photographs or records themselves.

Okay, so what have we learned? Number everything, be obsessive, and track. I expect this from anyone who ever thinks about doing this sort of work.

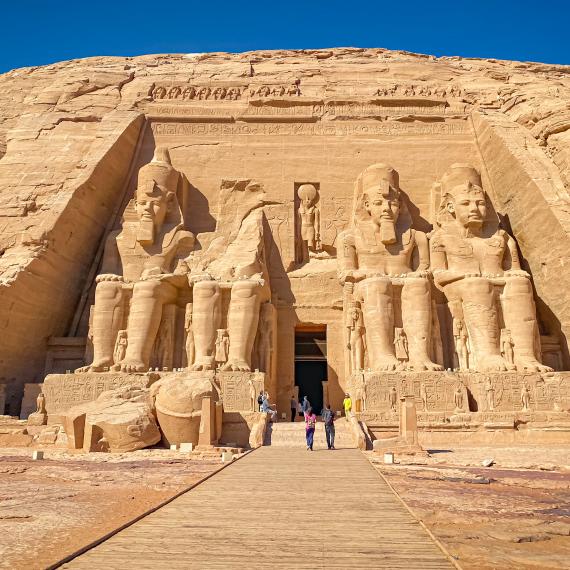

Okay, so I thought I should show you where the places are I've been talking about. So, Abydos, you can see, is the top red star; Karnak, Luxor, etcetera, they're the second red star; and the other star is actually related to Esna, which was where that jar from, the 30-E jar that Garstang collected came from.

Okay. So, our earliest group of objects, I probably should have put the blue thing back again. So, there's, I'm sure— There's unequivocally, I’m positive, these came from Thomas Shekleton Henry in 1897. So, we have one of the sheets of linen mummy wrapping. The linen there. The finer-grained one. We have two snakes on the left, bottom left. The coiled one is a cobra and the rear-fanged snake is in the— Well, it's actually, all that's left of the snake itself are those little bones. There's the linen, and there's his coffin, the little snake coffin that it was in.

What I don't know, because the snake man in the early 70s did not keep very good records, I don't know whether he unwrapped it to find the bones inside the coffin or whether it was all just all over the place by the time he looked at it. But at least he could identify it, which is very nice.

So, what else do we have there? We have two calcite jars. And one of the organic chemists has actually looked at it, tried to identify the fats and the lipids that are in those. And I think he found, I think it was goose fat or something on one of them, which I thought was quite surprising.

The stone image I mentioned is above, the canopic jar top. I think that originally went to the Art Gallery and then came back to the Museum. And that, below that funny looking thing is an almost headless mummified hawk. A little Falco columbarius.

The next absolutely unequivocal thing from T. S. Henry is this sycamore box. And some of the elements that were inside it— The very valiant Heather finally decided enough was enough and we shouldn't have this rattling around because it was falling apart and might actually be really important. We have two, no, three metre-square boxes where she's pulled out, cardboard boxes where she's pulled out all the elements and put them in, tried to put them in order. So, all those little segments of the wrapped flowers, the wrapped garland.

So, those are the things we know came from T. S. Henry. We don't necessarily know that they came from Thebes.

Back in [1983], a very young Moya Smith did a short week— No, it was meant to go on for a day. Egypt at the Museum. We had it on for Museum Day and something like 10,000 people came to see it. Horrifyingly for them, I think it was on the fifth floor. The lifts jammed and everyone had to walk up the flights of stairs. I just sat there. <laughs>

Anyway, so those are the mummified heads. I've obscured the heads because it's not really, I don't think, culturally appropriate to show unwrapped human remains. But they are there. We did have them x-rayed. The other x-ray is not actually from T. S. Henry. That one there, that's our, the most famous of our Egyptian objects; what is meant to be a mummified cat which was probably studied more than any other object in the universe.

It's actually not a cat. It's a fragment of human femur and another broken bone. And the State forensic anthropologist is absolutely positive it's a fabrication, a function of World War One collecting. I still like to think that, look, you can get interesting saw marks on bone and people could use bone in all sorts of ways. But this is part of the creation of artefacts for many, many soldiers in Egypt during World War One, and World War Two, probably, and ongoing. Not just for soldiers.

So, these are the Path centre staff who helped. Alanah Buck, who's the state forensic anthropologist. Pierre Fillion, Neil Hicks, and Steve Knott, who looked at the teeth. They looked at the hair. They looked at absolutely everything. I've never seen so many people try and crowd into a CT scanner room in my life.

So, the man, the top skull, had massive damage to one of his upper left teeth. The idea, looking like he’d had a twig that he'd been just going like this with. Maybe he was a scribe. Maybe it wasn’t a twig. His nose was damaged extensively during brain removal, and he had dark brown hair.

The woman had beautiful linen packing still impressed into her. Some impressed into her skull, but also some inside to plump out her cheeks. They think she had, probably, red hair rather than sort of ochre, but red, naturally red hair. And traces of honey as a part of the preserving mixture. And of course, down the bottom are the two sheets of linen that I'm positive are T. S. Henry's.

We've found other references to Henry through Trove. We hadn't seen this one, and possibly because—I've left it down the bottom—possibly because his name was listed as ‘Jïenry’ as opposed to Henry. So, I'm not quite sure how we found it. Still, I've corrected it now on Trove. It's Henry.

What I was particularly interested in— Oh, I should mention that we, Ross was looking for stuff about the Nubian skirt because we were talking to the local Sudanese community. The human remains have actually been repatriated to New Zealand about fifteen years ago. But what I really thought was interesting was this description: ‘portions of coffin’ and ‘casing of coffin.’

Now, I don't know whether you remember the blue list where it just said three fragments of a sarcophagus. So, I thought, “Ah! Well, that means casing of a coffin is clearly meant to be something other than wood. That must be the cartonnage we have in the collection.” See, I'm rather leaping at anything to try and make it so. It still leaves us—Well, unfortunately it didn't have a number. It would have been nice if they’d said exactly how many portions of a coffin, how many pieces of casing of a coffin. But at least, I thought, well, this puts us on the right pathway. I'm so easily pleased.

So, unfortunately, in our unnumbered group of Egyptian objects that could be described as fragments of coffins, or casings, or something else like that, we have six pieces, not three.

One of them, I suspect, may actually be recent. I kind of think this one might have been made by the woman working on the collection in the '60s. But we haven't done the testing to demonstrate that. But so, we've got six objects and three numbers to attribute. So, I thought, well, let's just sidetrack for a minute and think about, what do we know about the donor? Does knowing anything about him help us work out where he might have gotten stuff from?

Thomas Shekleton Henry, born 1864, 1865, or 1866; died in 1934, 1935 or 1936, depending on where you where you look for records. He was a water colour artist. He was an architect. He was an associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects. He trained and worked in London. He worked and travelled in Europe and U.S.A. He travelled to England. Travelled back to Australia. He was employed by the Queensland government. Employed by Lloyd Taylor and F. A. Fitz Architects in Melbourne in 1890. In 1894 he wrote an amazing book called ‘Spookland.’ He was employed as a draughtsman by the WA Department of Works in 1897 and by the Queensland Works in 1907, resigned in 1908. He was an early president of the WA Water Colour Painters Association. And, for Edna, he was her uncle by marriage. And this is where I let myself down as an anthropologist. I didn't do a serious, fulsome and appropriate interview, and I regret this deeply because I now can't track her or her descendants either.

So, she said he left his wife in England—sort of ran away, basically—and married another person here. So, he may have had two families or he may not. He married— What is this? He was her uncle by marriage. Edna's aunt's husband. His daughter was four years older than Edna and they played together. Quote, “He did a lot of travelling. He was an archaeologist, and the family tradition was that he obtained all these objects from a friend who was excavating in Thebes and who he visited on a trip between Australia and England.”

But that may be just so much story. Jasmine did track down the family in England. You didn't, I think, learn much more about him at all, except that you, I also saw— You said, I think, he had a couple of other objects. They had a couple of other Egyptian mummy bits floating around in a cupboard or in the drawer.

Jasmine Day: Drawer heads—

Moya Smith: <laughs> Drawer heads!

Jasmine Day: —to auction without any provenance listed and sent with them.

Moya Smith: So, you'll never track, we’ll never track them. So, theoretically, when these came in, they were said to all be around 1000 BCE, but there's absolutely no evidence by this. There was an article by someone interested in his art that suggests that he was on an expedition to Nubia as an expedition artist, but I can find no reference to an English expedition to Nubia with him as the expedition artist. So, he continues to be elusive.

So, I thought it would be interesting to see some of his art, just to look at the times when he was in various places. So, Hobart in 1890, then the WA Governor's residence in 1912. Now he’s, in 1914, the town hall in 1914 as well. And one I wish I had found before it went to auction, because this is the only painting of his we've seen of Egypt. This is Karnak in 1892.

So, it seems to me that he does seem to have travelled backwards and forwards. I just don't know any of the dates, because trying to track, even with Ancestry or something, trying to track incoming and outgoing people— T. S. Henry. There are so many T. Henrys you just don't know whether you've got the right person. So, it's very sad. But that's just, that's a gem.

Okay, so there’s also this wonderful book called ‘Spookland.’ It says—I found an article that talked about this, it said: “T. S. Henry regarded himself as an objective and careful participant in spiritual settings and seances. He’d attended as an interested party, a number of seances at which, according to later argument, he was deeply affected and even overpowered by his experiences. However, he was determined to be seen publicly as a rational and calm thinker and something of an investigator.”

So, in September 1894, he was one of a group who attended a séance conducted by Mr. and Mrs. Mellon at the residence of Dr. Charles McCarthy in Elizabeth Street, Sydney, near where the Hyde Park obelisk is now; and he was witness to Mrs. Mellon sitting behind a curtained off corner of the room in low gaslight controlled by her husband, giving just enough light to make out the various objects in the room. And quite clearly what he thought he saw was her creating the spiritual event. <laughs>

So, in December 1894, he published a booklet, a record of research and experiment in a much talked of realm of mystery, with a review and criticism of the so-called phenomena of spirit materialisation, and hints and illustrations as to the possibility of producing of the same.

Now, however, his debunking of spiritualists, possibly not very easy when so many of the luminaries of Sydney at the time were true believers. So, eventually he moved to Melbourne, to get away, I think, from the turmoil he had created in Sydney, and in 1914 he returned to England. He doesn't seem to have come back to Australia after 1914. He continued his work as an architect and painter so some of his paintings have been identified as late as 1920 and there was, in fact, an exhibition of his work, I think, in Perth in 1920. Whether he came back for it or not is a bit unclear. So, he lived in London and died in Essex in 1934.

We know he went to Karnak <laugh> so he’s close to Thebes. Well, I mean, he is in Thebes, in greater Thebes. So, I thought, well, Thebes is a specified source of our early materials— It’s a bit difficult. So, if he was there, then how did he acquire the material?

There are no numbers on them and, as you know, even at this period, excavators are writing numbers on their excavated stuff. So, had they come legitimately from an excavation, even if that was part of the partage, they would have been numbered. So, they're not— They don't have a clear track record.

So it says 1898 for Luxor, but in fact it's 1857. I think 1898 was the year this was registered. The picture, the photograph on the left from Francis Frith. And he has done a wonderful two-volume of some of his early photographs in Egypt and Nubia. So, there's the landing in Luxor.

So then, from the Royal Collection Trust, that's a black and white version of their coloured water colour—you can't really have a black and white water colour, sorry—of their water colour with an excavation at Gournah for Prince Edward, the Prince of Wales, who was allowed to keep what he liked, basically, probably including the mummy. And I do recall there was one that came out for—I can’t remember whether it was ‘Secrets of the afterlife’ or ‘History of the world in 100 objects’— where [it] had been part of this collection, possibly from this acquisition process of the Prince of Wales.

So, people are acquiring things. There’s a lovely, then, lovely reference. This is 1892, the same year that T. S. Henry is there painting Karnak. The Baedeker for the District of Thebes talks about, “All the consuls sell antiquities.” This is my favourite line, I think. “Best from Todrus,” Moharb Todrus, the German consul. He goes on to say, “the consular agents, the British and Russian, Ahmend Effendi; the American, Ali Murad; the German, Moharb Todrus; all the consuls sell antiquities.”

So, then... the guide, ‘The Traveller in Thebes: A handbook for travellers, part two. Guide to travel Upper Egypt with Nubia as far as the second cataract and the Western oases.’ So: “The traveller in Thebes is frequently tempted to purchase antiquities. Half the population of Luxor is engaged in traffic with antiquities, and the practice of fabricating scarabs and other articles frequently found in tombs is by no means unknown to the other half. Many of the articles offered for trade are so skilfully imitated that even experts are sometimes in doubt as to their genuine-ness. Those who desire a genuine memorial of antiquity should apply to the director of the hotel or to one of the above named consular agents”. And then he lists “good and reliable specimens may be obtained” from a certain couple of people.

So, as well as there is the consular, ah, consuls actively involved in trade, and the accessibility of material for, say, T. S. Henry to buy and for everyone else to buy, Cook's tours are operating since 1869. So, tours along the Nile also trade in antiquities, both quasi legal and looting. So, you can imagine that the cruise ship photographed by Beato in the 1890s, possibly even the cruise ship in the late 1990s, a century later, also offered antiquities for sale. All I would say is, be careful what you buy.

Well, I guess we now come back to, can we actually identify any of these portions of coffin, or casing of coffin? Just like in the 1960s, no matter whether we know about it or not, the stripy coffin face is on display.

And when it went on, one of my colleagues thought he'd found the answer. Looking through the paperwork, he found what looked like correspondence between John Garstang and the director saying what was offered. And what was offered were coffin fragments from Beni Hasan. What he's missed is a bit that they were meant to have hieroglyphs.

So, he'd written this up as coming from Garstang. I thought, oh, okay, great, we really know this. This is fine. So, that work was done about ten years ago. It was only when I went back to have a closer look. I thought, no, it's not. It can't possibly be from Garstang. We have nothing. There's no correspondence from Garstang saying he’s sending us anything other than pottery. And Beni Hasan material was always all beautifully numbered and this just doesn't look like it would possibly have come from Beni Hasan.

Okay, these are the objects. Here we go again. What are our options? So, is Thebes a possible source for any of these objects? So, the stripy faced coffin, the small cut out coffin there, the hand with the document scroll, the foot, and the cartonnage down the bottom.

So, the stripy faced coffin head. On the right, this is what it looks like when I started work and it's clearly poster paint. So, it was clearly added in the 1960s when the then curator, instead of writing numbers on things, had thought, well, we're never going to know what this is. Let's make it useful! Let's show, let's have it for education and for Museum visitors. Show it as bright as it might once have looked.

Now, fortunately, our amazing conservators managed to strip it back to what was basically a layer of resin or varnish between the poster paint and the original. So, they've got to the resin and stopped, which is really lovely.

Subsequently someone said to me, look, every New Kingdom specialist has visited the collection. And there’s been heaps of them. They’ve all said, “Okay, this is New Kingdom. This is Thutmose III, around 1479 to 1426.” They’re all absolutely— Every single one of them has said this. I thought, great.

If you can look at the top of the profile shot you might just be able to pick up, upside down, the goddess enfolding the head and truncated by being hacked off the rest of the coffin.

So, okay, well, I'd like to be a believer. What else have we find out about it? Susanna Binder said, “Look, it's glittering. Have you had it checked to see if it's gold?” Well, it's not gold. There are traces of orpiment, which is arsenic sulphide, which was effectively poor man’s gold. It would give you that same glittering effect, that same connection with the gods.

I wonder, though, with the black stripy wig rather than blue, maybe it's closer to the 21st Dynasty Amun priestly coffins. A cache of coffins from that period, the Amun priesthood have been found, were found near Deir el Bahri, Hatshepsut's mortuary temple. And an extraordinary amount of work has been done on those. And many of those also, a) they look they look similar, b) they have, all of them seem to have traces of orpiment as something, as a decoration. Haven't quite got there, but it's interesting.

Okay, this one, the hand. Well, it too is consistent with removed hands from the Amun priestly cache, and these are a couple of coffins from the [Rijksmuseum van Oudheden]. And what you can see there is that hacking off of hands. So, even during the excavation process, things didn't stream, come out smoothly, out of the ground and into a collection. People were getting into them, pulling off bits, distributing them, moving them, selling them. So, possibly that is, that sort of hand could have come from a coffin like that. And it's said to be a— I think it's meant to be a very Theban type of hand with a document scroll like that.

Cartonnage. I live so much in hope. <laughs> So the closest parallel, again, I found is at Deir el Bahri. See, I'm really pushing it all. I have absolutely no idea. I also can't quite work out which angle this thing should be positioned. I don't think it's like that. It's around the shoulder, around the body. The piece on the left, I think, is the one that I strongly suspect was made by the same curator who painted the coffin head bright yellow.

So, this is an example, similar sort of thing, similar colour suite as well, from Deir el Bahri, found in the 1930s. I'm just trying to push the agenda that, hey, guys, these things all come from Deir el Bahri. It must be Theban. They must, ah, must be... must be from T. S. Henry... I'm never going to get the answer. Look, I have to— I know that. I'm just pushing it.

So, that's a view— It's in this general area in front of the mortuary temple that those sorts of, those caches are found. That sort of excavation. So, with Hatshepsut's mortuary temple behind you, I'm looking back towards the Nile. So, big area to be hunting for more caches.

So, this particular gem, it's only been identified stylistically. Peter Lacovara has said it's late period, Dynasties 27 to 30, and it has all the characteristics of that period as well, with the holes for the separate pegs to be inserted. So, it's a panel inserted into something else. And I'm not sure there's a geographical focus to these. If they're focused at Thebes, I may as well give up right now.

I have absolutely, absolutely drawn a blank on this one. I think it's the foot of a ‘ka’ statue. I don't know what period. I don't know where it might be from. So, there's a hell of a lot more work to do there. But I'm just going to go out here and say, look, I don't think that's from Thebes. <laughs> So, you really have to be a believer.

There are so many possible locations for material. When you say Thebes, these are the possible locations. It's a vast area. Thousands of years. So much, so much stuff, a lot of it distributed in museums around the world. So, from the east bank of the Nile with Luxor and Karnak to the mortuary temples, and then the burials on the left bank and the workers village. So, you've got heaps of options.

So, looking back towards the Valley of the Kings. So, Hatshepsut's Deir el Bahri there. You’re actually looking from behind things. So the Valley of the Kings is over behind that and I think you just see a little pointy bit, which is called the Mountain, the Pyramid, and workers villages also over there.

I love this. This is such a nice a nice sort of pairing of 1857 and 2005 with the Pyramid. All I’m trying to emphasise is that these are potential locations and they've been known for a long time. So, you can see the early photographs and you can see more recent photographs. So, Valley of the Kings.

Deir el Medina, the Workers village. The village itself is a bit... There’s a section here and round it is a temple and then tombs.

And Luxor itself. So, you know, he had plenty of opportunity for these— Plenty of opportunity to acquire things there, and plenty of options for where they might have come from. I still like to think Deir el Bahri, given that the excavations were happening in the year he arrived in 1892, when we know he was there because he's painting Karnak... I think that might be a really nice thing if we could ever, ever prove it.

So. Well, we know— We haven't been able to say, yeah, we know for sure where they come from, so we just keep plodding along, trying to find out what we can say about things at all. And the first thing we try and do is date them.

The next thing will be with the plant samples to analyse things, to identify the plants, to identify, do all sorts of science-y things—hello, it’s Science Week—do all sorts of science-y things and look at the structure of the paints, look at the structure of the resins, look at the contents. Everything we can actually think about and show at it.

So, we use accelerated AMS dates, mass spectrometer dates. You need a much smaller sample and you get a much tighter, tighter range of date. So, what's happening? So, this is the box. The box dates to the 27th Dynasty, which is the Persian period. And that's Annie Carson from anthropology and archaeology, bravely taking the sample when I chickened out because I thought, you know, I might cut too big a bit of out of the box. Thought it’d lasted quite a long time. I didn't want to be the one to kill it.

And the contents of the box. This is where I think I mentioned Heather had taken out all the contents, and it's something like, I think, three metre-squares of stuff. But this is the sort of thing they might well be.

Well, it’s later, this is— The garland, regrettably, is older than the box, which doesn't make for a tidy, tidy wrap up. <laughs> So, the dating laboratory said, “Well, perhaps they treasured the garland and kept it and then put it into the box later.” I thought, yeah... I don't think so. <laughs> Salima Ikram and Susanne Binder have both looked at the box and said, “Oh, we think it's actually a shabti box.” So what we have, I think, is looting and creating an artefact for sale.

The fact that they've created it out of something that is in itself ancient is quite nice, but it just, it changes the narrative, doesn't it? So, those are the sorts— So, further work to do on the garland now that we've got a date, or even without getting a date, is to identify the species and try and work out how it might go back together.

Well, it’s lovely to see what the 21st AD embalmers did when they rewrapped and re-embellished that wonderful 18th Dynasty mummy that was found— Oh, when did they do these? It was a cache of that relocation of the Royal Burials. So, it's a very similar, very similar sort of structure. Bands and bands and bands of flowers and little sort of little packets of flowers in persea leaf.

And the moral of the story is, there are an enormous number fakes out there. That always remains a risk, that the material we're looking at that Henry bought is also forged, also fakes. I think all of, everything needs to be dated at the very least to see if they are actually ancient, though, of course, people can use ancient wood to create new objects.

I will say, with the sycamore box for example, that Maarten Raven from the [Rijksmuseum van Oudheden], years ago said, “I don't think those two objects go together.” And Amani Hana, who’s a Coptic woman working here said, “Surely that's Late Period.” So, she was pretty close. She was right. So, it's distinctive and she's seen things coming up in exhibitions that look like that, just not with garlands in them.

So, despite all my incredible optimism— I was so sure when I came to talk to you I’d be able to say I know for certain that the stripy face <laughs> and the cartonnage shoulder and the hand are the things collected by T. S. Henry. Regrettably, I can't actually say that. I can say I think they’re Theban, and I can say I really hope that they come from Deir el Bahri.

But really, they're just more wonderful things in our own Museum’s Egyptian collection. Thank you.

<applause>

Sarah Williams: Thanks again, so much, Moya. Sounds like such a dilemma. <Moya laughs> Well, I was wondering if anyone has any questions. We've got a couple of minutes.

Moya Smith: Make it simple, Jasmine. Be kind to me. Jasmine did say— I should have said. Twenty years ago, she said, “I don't think these are Garstang. I think they're T. S. Henry.” So, I should have listened. <laughs>

Jasmine Day: Oh, thank you for a fascinating talk, Moya. And I have learned a lot today that we haven't had time to discuss, about what you’ve found in the collection. What you just said near the end in referring to Kim Ryholt's work. You were talking about the recent dating of the— Now, we know it's a shabti box.

Moya Smith. Mmmm.

Jasmine Day: And also it's got the— Well, maybe a shabti box.

Moya Smith: It's a box.

Jasmine Day: It's a box. And then it's got this garland, or maybe it wasn't even a complete garland, sort of stuffed into it and would’ve been probably broken in the process. And you've dated them both and found they’ve got a different date.

Moya Smith: Yeah.

Jasmine Day: So, what are they doing together? And I do find in looking at things which are still available today on places like eBay, maybe smaller things and mostly jewellery-style objects that are from old collections, that one of the number one traits of things being on the antiquities market is that you get a combination of things which weren't from the same place or the same period or the same purpose.

Moya Smith: Mmmm.

Jasmine Day: Or somebody will go to one tomb and grab a box and some will go to another tomb and grab some broken flowers and stuff them together and say voila, artefact. And exactly as you say, I would strongly suspect the moment you said that, I thought, ah ha. The antiquities market.

Moya Smith: Yes, creating the Egyptian artefact for the unwary buyer.

Jasmine Day: Yes, and I think I may have said to you privately beforehand— If you were to look again on the back of all of the coffin faces that we've got, is there any sign that at some point in the past they had something screwed into them, like a hook or for a hanger?

Moya Smith: Surprisingly, no. Surprisingly.

Jasmine Day: Right. Okay. Because again, that can be a sign that they were from an antiquities shop. They were displayed on the wall. And I have seen in some other museum collections, like Swansea in Wales, I've seen one that they took out for me. We turned it over. On the back, it's got the holes and I've seen other ones—

Moya Smith: You’ve got to also be wary, though, that was museum hanging practice in the 1890s as well. Because we do have things that we know came in directly from the community that have been hung with copper hooks and pieces of wire and bizarre things.

Jasmine Day: And the cat I'm very interested in <Moya laughs> because, of course, that is a perfect example of antiquities market. Take a human bone, take some random mummy wrappings, wrap them together, call it a mummified cat. Voila.

Moya Smith: I so wanted the cat to be real. <laughs> His family, his descendants, had been in to see it. They said, “So, what, grandad sold you a pup?” <laughs> I said, “No, grandad believed it was real. Grandad believed.”

Jasmine Day: Yes, so, I think as Ryholt himself says, little research overall has been done on the antiquities market, how it operated, what kind of objects there were. I think I'm—maybe this is a thought bubble—but I think I'm seeing a difference between the quality of material sold by professional dealers, upfront in-your-face dealers with the shop, and blokes on the street saying, “Would you like a shabti?” and they lift up their coat.

Moya Smith: I think, don't take anything from someone on the street because if it's real, you'll be in trouble.

Jasmine Day: Yes, so, I'm getting very interested in the stuff from the blokes on the street and I'm actually starting to collect some of the stuff that might come from there.

Moya Smith: Well, I think we’ve got [stuff from] blokes on the street.

Jasmine Day: Yeah?

Moya Smith: I don't know. I just wish we knew more about him. Because if it's not blokes on the street and it's his buddies who are digging, it makes it actually really problematic as a museum. I mean, we'd be better off with stuff from the blokes on the street. But it’s such a great thing. It's such a wonderful topic to be pursuing. I’m really looking forward to your book. <laughs>

Jasmine Day: Yeah. And last point would be that maybe one future direction for further research going into the future is looking at what, as you say, what excavations were happening around the area at the time when T. S. Henry was there, but also illegal excavations as well; because what was legal and what was illegal was a fine line between them back then.

Moya Smith: With Thebes as one of the major entrepot of looting and sale of looted material … Ryholt says ... It's really worth tracing that on YouTube just to see his talk. The families, the multi, intergenerational families of looters. And I forget was heading. Because it's such a major thing, you’ve just got no— You don't know.

I mean, the looters themselves have collections. They've bunged it into the— They've got it in their storage rooms. It's going to come out— You don't know if they’re... Just so much we don't know. But Thebes is a looter's paradise.

Jasmine Day: Yes. And this is where diaries are starting to come into interest and people have started to collect diaries of these people. And also, as you say, I think talking to members of families and descendants is really important. It’s ethnography.

Moya Smith: Yes. So, if anyone knows any Ellery family members in Perth and wants to see if they're related to Edna and whether they have diaries, I'd be really happy to hear about it.

Audience member: Just from a, like, palaeobotany perspective, have you looked into or taken any core samples of the timber itself and then tried to recreate the landscape of the way— What material it is and where it could be placed around the sites?

Moya Smith: No. But it’s a brilliant idea. I mean, we’re just trying to think what are the things we really should be doing.

Audience member: And geomorphologically, what’s preserved, as well?

Moya Smith: Yeah. Well, I mean, not just the palaeobotany of the box but, I mean, there's so much to do there.

Audience member: And the landscape itself, from a geomorphological perspective. How has it, how has it changed? Has it been affected by water? Has it been affected by sand pressure? These sorts of things. And are you finding it at a certain levels...

Moya Smith: So, because we don't know and, not knowing source, you're limited to what you might get from it if it's not captured in the object itself. But there’s some really good people who specialise in this field at UWA. So, I was flaunting this at them when they brought the students around a couple of weeks ago, thinking, come on, come on, come on... You tell them.

Audience member 1: eg Shane Burke at Notre Dame.

Moya Smith: Yes. Well, I mean, tell him this stuff’s here, if he's got students that want to think about exploring the Egyptian collection.

Audience member 2: Just following up your throwaway comment before about— And I think you were referring to the ethics of whether it's on the street or if it was a looter. I'm just interested. Could you pursue that? Why do you think, I'm assuming it is ethically, that it would have been better to get it from someone on the street than if it had been sold incorrectly—? If you can just unpack that.

Moya Smith: I'm probably not terribly clear about what I was thinking about that. I think I mean, the ethics of collecting in Egypt are probably shaky no matter what was happening. I think the movement of material from excavators, at least, is more transparent. People on the street are often, I think, known to authorities and almost, I'd say, licenced informally. But just blank looters that are just getting it and sort of shoving it out anywhere, there's no control. There's also no possibly, there's very little possibility of tracking things back to source. That would be theft if he'd got it like that from a friend who was excavating.

Because the thing about the excavators is there was a sense that you would rely on them to be behaving appropriately. So, it should have been recorded. It should have been partaged. There should have been something. There was a formal record somewhere. In all systems, that transference of ownership, custodianship, whatever you want to call it.

Look, ownership of this material is vexed anyway, I think. I mean, I think in a funny way the Museum is very lucky not to have things that are violently significant because, really, you would have no recourse but to return them immediately, frankly.

I still have made a point of making sure that visiting Egyptians know what we've got, because I just think— Part of this is that thing about having sort of the electronic databases up so that people know what's there and just looking at what's available in sort of antique stores and thinking, where's this coming from? There’s a legal framework for ownership and that's one of the things that we're very keen to do, is interrogate all our collections and look at how we acquired them.

We don't have the big sort of glossy collections, say, that the international museums have. We don't have the statues of Tutankhamun or the golden whatevers or the Buddhas or whatever. We don't have Benin bronzes. You would have to look really closely at everything you have.

I mean, the idea of ownership is so transient, I think, that a museum has to be able to say, “we feel that we are the legitimate owners of this,” in conversation with source communities, source country, whatever.

There would be one problem I think we face, what do you do in situations of war and usurpation of cultural authority?

Audience member 2: But if you take the Aboriginal notion instead of saying the museum “owns,” couldn’t you say the museum is a custodian—

Moya Smith: The museum cares for? Oh, we do, we do say custodian. I mean, “owns”, I always think of it in inverted commas. I mean, it's actually a really exciting time to be in museums. I mean, I think these are sort of human issues and social issues that are really fun to be part of.

Audience member 3: Thank you, Moya. Fascinating presentation. So, my question is related to more the profession of curating as a whole, industry wide. At Boola Bardip specifically, is the method of cataloguing within the Egyptian and anthropology department, is that consistent across the whole Museum? <Moya laughs> Or, for example, are you battling with a different system to that of the Greco-Roman collections or the modern historical collections? Or is it a consistent— For example, the donor number system’s the same?

Moya Smith: They're pretty much the same and we're all moving to the same database. The only thing that we do that everyone else says, which [the Department of] History, who trains people on how to look after collections, laughs at, is that we still have written registers. But we've caught so many times those mistakes in the database that we are quite keen to have written registers.

And that's also, we’re traditionalists as archaeologists. <laughs> I will fight to keep the written register to my dying day. <audience laughs> No matter what happens with our wonderful new electronic database systems. I'm just not a believer in— Come Armageddon, I'll run out the door with the written register so we'll know what we've lost. <laughs> So, it is interesting. Similar systems, similar processes.

Audience member 3: But there’s always slight differences.

Moya Smith: But always slight differences. Yeah. I think what will be very interesting as we move to a unified database system across the Museum. And this will be very, very interesting and there should be much more parity—is that the word I want?—even if we still do things differently.

Anyway, thank you. Thank you so much everyone for coming.

<audience applause>

More Episodes

John Mirosevich explores the varied history of Thonis-Heracleion, Egypt’s greatest Mediterranean port for 400 years.

Listen to Hon Dr Anne Aly MP who joined us at Afterlife Bar for a presentation on the Discoveries of Ancient Egypt exhibition.

Join committee members of The Ancient Egypt Society of WA Inc for a unique opportunity to dig deeper into Egyptology.

Dean Kubank revisits the Temples of Nubia and the enchanting Temple of Isis at Philae.

Celestial Timekeeping in Ancient Egypt - Discover how Ancient Egyptians used the heliacal rising and setting of stars to construct their star clocks and civil calendar.

The life of the average Egyptian could sometimes be precarious and short. Broken bones, infections, and arthritis were all common among the general population.

Discover the story of the pharaoh Djedkare, his family and courtiers, and take advantage of the rare opportunity to hear from visiting international Egyptologist Dr. Hana Vymazalová of Charles University, Prague.

Discover the story of the pharaoh Djedkare, his family and courtiers, and take advantage of the rare opportunity to hear from visiting international Egyptologist Dr. Mohamed Megahed of Charles University, Prague.

Discover Egypt’s ancient legends of creation, death and resurrection. Tales of Ra, Osiris, Isis and Horus will unlock the meanings of the art, religion and funerary practices of ancient Egypt.

The Dynasty 6 Vizier named Weni the Elder, who lived about four and a half thousand years ago, had a detailed biography written on the outside of his tomb.

How, when and why was mummification invented? The answers may surprise you.

Ancient Egyptian Astronomy Unraveled - Discover how the Ancient Egyptians used their knowledge of the sky to design and position their temples, statues, and roads.

As part of our evening Afterlife Bar series at WA Museum Boola Bardip, we welcome a series of speakers to dive deeper into Egypt. Join us this week as we hear from Dean Kubank on Temples and Tombs.

Renowned expert in ancient Egyptian history Daniel Soliman delivered a fascinating talk, as we celebrated the launch of the WA Museum Boola Bardip's Discovering Ancient Egypt exhibition.