The Life and Afterlife of a high ranking Egyptian by Heather Tunmore

The Dynasty 6 Vizier named Weni the Elder, who lived about four and a half thousand years ago, had a detailed biography written on the outside of his tomb.

This talk looks at the life outlined in the biography and the information found during the excavation of family tombs.

Heather is senior Epigrapher on the Abydos Middle Cemetery Project and Honorary Associate of the WA Museum. With the kind permission of the Egyptian Department of Tourism and Antiquities, Heather Tunmore has worked as part of an international team on the Abydos Middle Cemetery Project in Egypt for the past 16 years. She loves working with Old Kingdom art and really enjoys reassembling lost and broken fragments of art and hieroglyphs.”

-

Episode transcript

Event MC:

Good evening everybody, and welcome to the WA Museum Boola Bardip and the Discovering Ancient Egypt Exhibition. Before we get started with our guest speaker for this evening, I'd just like to take a moment to acknowledge the lands on which we are gathered on and learning here today, the lands of the Whadjuk people of the the Nyoongar nation. I'd also like to pay our respects to their elders, past and present.

This evening we have Heather speaking to you about the life and afterlife of an ancient Egyptian noble. Please put your hands together and welcome Heather.

Heather Tunmore:

Okay. Before I start, I'd like to acknowledge the Department of Antiquities in Egypt and thank them for allowing me to work in Egypt alongside their people for the last 40 years. So, a long time! And I'd also like to thank the Department of Archeology and Anthropology at this museum for the fun we've had working together for the last 40 odd years. Something like that.

Okay. I'm going to talk to you tonight. I'm going to pick this up mid-stream because I didn't quite finish it last time and talk to you about a man called Weni who was a noble (well, he was a high official. There's all sorts of arguments about whether it's nobility or whether you say officials) in the very end of the old kingdoms, so about four and a half thousand years ago. And his tomb was found in the 1860s by a man named Mariette, who was the person in charge of the antiquities department in Egypt at that time.

Most of the material that was found in Egypt in the 19th century, in the early 20th century, was taken out of Egypt and it became taken away from its context. So, you had material in isolation. So, if you look at what's in this really, really very nice exhibition here, you'll see a lot of material that has been taken out of its context. You'll have a look if you're going to look at it again and see where it comes from. It might just say ‘Abydos’. It might just say ‘Saqqara’. It might say ‘maybe Saqqara’. ‘Maybe Abydos’. And you've got one thing and you don't really know where it comes from. So too often the find spots were never recorded. So, you're looking at material in isolation from its context.

So, when his Tomb was discovered in the 1860s and the best of it was taken up to Cairo and most of it was lost. And all they had left was the biography. And the biography told the history of the times. It became famous because it was a historical document that told us and still tells us more than any other historical document, what was happening in Egypt at that time. And so, it became a history of the times as it was read by modern people. Not a history of the times as it was read within its context by people at the time. If that makes any sense at all. So, I came across it in the 1960s, the late 1960s, I hasten to add, when I was first at university doing Egyptian history and language and this is how I saw it. Commentary in German and the hieroglyphs written or typeset, I suppose it must have been in some way, reading left to right and down the page as if you're reading a modern book. And it gave you information about him and who he was and the fact that he lived in His Majesty's heart.

He was very close to the King, and he had been a trusted advisor, confidante of kings, the judge. He judged the queen and the harem for the endless, well, inevitable, I should say, harem conspiracies that happened in Egypt over the years. He tells us he took thousands, tens of thousands of troops to fight in what we now call the Sinai. Five times. He moved massive amounts of stone down the river, and he helped build the King's Pyramids.

He went right down into what is what we would now call northern Sudan. Cut canals through the cataract, brought back massive stone barges that he had actually built in the Sudan from wood that he found down there and ferried them back up through the cataracts all the way to Saqqara. And I mean, they'd have to do that on a pretty high flood to be able to get it down there. Well, so I think.

He was given a beautiful sarcophagus and a lid, a doorway, a lintel, a door jam or door jams and libation, offering table for himself from the royal quarry. So, he was thought really highly of by the king, and he was ultimately promoted, so the biography says, to the rank of count, really high noble and to the equally high administrative position of Governor of the South. What we call Upper Egypt, because they were all in the northern hemisphere and we're down here. So it's the opposite. But this was just in isolation. They weren't looking at this piece of stone with this writing within the context that it was found. Within the context of the tomb and the cemeteries at Abydos. And so, the assumption was made startlingly enough that he was a self-made man.

And recommended reading for the class that I attended was Sir Alan Gardiner’s Egypt of the Pharaohs, which talked about an insignificant slab of stone. Talked about a man of humble birth Talked about a man who rose to one of the most exalted positions in the land. And he goes on to say that after a long and meritorious career, how could he have actually been able to say the pharaoh did all this? I didn't do this. He must have been a person with an extra dose of obsequiousness, if that makes sense. And this was not just Gardiner, this was everybody. And we were encouraged to believe that the gradual loss of centralized power towards the end of the old kingdom meant that Weni was an example of a group of men who rose to prominence because they were good at what they did, not necessarily because they were not princes of the realm, as it were.

And this is the insignificant piece of stone, which when I actually came across it in the flesh, was about three meters wide, over a meter high and nearly half a meter thick. Nothing much insignificant about that. And yes, it's a mess. It's a mess because it was hung on the outside of a tomb chapel for four thousand years. So, yes, it's going to be rather badly weathered. And when Mariette moved it off the wall, it broke in half. And bits fell off from various edges. Yeah, yeah, yeah. It was his tomb, and his biography was inserted onto the outside wall. And this is one of the things that we found in the sand that were, that had fallen off the right-hand bottom edge of the. And it's pretty important because you've got Weni sitting on a chair and at the bottom it says ‘he says’ and at the top it's got the remains of the [unintelligible 09:20], which is Weni the Elder.

Okay. And when they copied it down, it became obvious that it reads across the top, reads down the side and then down the side facing that way. So that the top is the offerings. You know, please say a thousand bread. Please say a thousand jugs of beer. Please say a thousand oxen for me to live and eat in the afterlife. And then down the right-hand side, it gives his name and titles. And then it goes across reading down, but facing the other way. Now that when you read these, you read into the faces. So, you can always tell which way to read the hieroglyphs because if you're looking at a face, you read into the face. So, the lines go from right to left or left to right, depending or up to down as well. So, this way you're reading down here and they're looking that way. Then they're looking that way. So, you're reading across there.

And the first part of it refers to the Pharaohs Teti and Pepi, and the other part of it refers to the Pharaoh Merenre. And on the far left-hand side, you have two columns that refer to his parents and his brothers, and they do not give them any titles. And as you can see, he's sitting there at the bottom, not sitting sorry, he's standing there at the bottom and he's like this.

And so all of this meant that the interpretation was that this is a man of humble birth. His parents had no titles and his, he's sitting there not with a staff and a scepter but bowing. So therefore, he's of no high rank. Originally.

When you actually look at the way in which is divided up across the top, down the side, across the, about two thirds of the way, maybe to here. And the tone changes from here to here. It changes because in the first one he's talking about the first period of his life, and then he goes to the pharaoh, Merenre, who reigned for about nine years. And it becomes very formal and it starts to talk about Merenre. It starts to talk about what happened at that stage as if he's quoting from official documents.

And so, the theory is that he's actually, sorry not he’s actually, but the pharaoh has given him permission to use the official archives in his biography. And interestingly enough, when Mariette's people copied this, they left this line out. In fact, they left quite a bit out. It’s really hard being an epigrapher. And you can see there the top line and then that division coming down here. And it's sort of a bit of a dogleg.

When they when they brought the biography back to Cairo, they bought a few other odds and ends with them, which were subsequently lost. They turned up in the 20th century. And you have on the top left, a very fine carving of Weni from the waist up. You have his monumental false door on the right. In the middle, you've got a lintel. Bottom left, you've got a tiny statue with his name on it minus a head, and you've got two small obelisks that would have stood in front of his door, of his tomb.

And then in 1999, we rediscovered his tomb. And it was an enormous mastaba of huge mud bricks. The retaining walls were on a batter, slightly. They were 30 meters long on each side, the walls are three and a half meters thick, and the walls still rose five meters high. It was big. And it was deep. And it was burnt.

So, in the end of the old kingdom, beginning the first intermediate period or probably into the first intermediate period, it had been opened and robbed. Now it's very rare for a tomb in Egypt not to have been opened and robbed. You know, Tutankhamun's tomb was opened and robbed at least three times.

And so, you can see here at the back, the sarcophagus that was brought back for him from the king's quarries. And that's a close up. It was big. It was also had a tiny hole in it. And the tiniest person, which wasn't me, managed to squeeze into there and copy the hieroglyphs down. And that shows you what the tomb would have been like because that is where the sand came down and in when the tomb had been opened and left open.

And then when the fighting came down from the north, sorry, came up from the south and met the people coming down from the north and they trashed these tombs. That's what happened. It was burned and burned with oil. Deliberately burned. And so that's another story. But also, what was found was on the exterior of his north wall, a second false door. And this gives his titles one more time. But this time you have chief judge and vizier. So, the impartiality of the chief judge who sits behind the curtain and the vizier who is second in control in the land of the king. And so, he had, of course, the discussion is also whether this is posthumous. But that's another story.

And some of the, that's the chapel, some of the blocks were in situ. Some of them were on the ground. Some of them were found in the sand a few years later. Those are one of the ones in situ.

And you can see you've got a cow or oxen being led. With sacrifices here, all to be sacrificed for his eternal dinner. So, and that is ongoing. So those people are walking in on an ongoing basis. And then there's a butchery scene which we found in bits and put back together, showing the animals being butchered. And then further in you've got them on platters being offered for food. So, you've got the whole shooting match, as it were, I mean no guns.

And we found the bottom that went with the top and the bottom was in situ. Yeah. And that's his little chapel. And here the wall went straight up and that's where the biography would have been. Sitting on the outside for all to see. So, it was a public statement, the same as the false door on the north wall was a public statement.

And then in 2007, we found Iuu’s tomb and Iuu we knew was his father. It had been discovered by Lepsias in 1837 and promptly lost again and not found till 2007. And how do we know it was his father? Well, we found his false door, and his father was also chief judge and vizier. Where is it on there? Anyway, it is there. Chief judge and vizier. And Iuu and his father and I couldn't get a picture of the bottom very well. But you've got a, you've got an image of Iuu, sorry of Weni, his name, his son, offering to his father. So, it all begins to knit together.

And that's, that's the Iuu’s tomb chapel, the remains thereof. And that Iuu’s tomb. So, you had two massive mastaba’s. Now a mastaba is Arabic for bench and that is a bench shape tomb. Okay. So, somewhere later here I think I've got a picture I'm not sure. But they were they were big because you can see the size of those exterior walls with the mud brick and then you've got the tomb shaft going down and a group of us standing there very nervously because we're about to climb down there. It was scary.

And so there you have the mastaba of Iuu in the top and Weni just below. They’re very close together. And Idi, their cousin on the bottom. And this is on top of a hill, the white limestone standing out. Beautiful, absolutely beautiful. Big statements made about their allegiance to the king. The fact they were loyal.

So, he was not an insignificant member of the society. He was a member of the elite. And therefore, even for those who could not read hieroglyphs, because the literacy rate in Egypt wasn't very good, wasn’t very high, they were functionally literate in the sense that could read what was being said there in the terms of the way that he was standing. He was giving honor to the king. And the king is here in the form of the cartouches Merenre. And so it's symbolic, if you like, but certainly it is very, very clear. And for all. So, it was public and publicly available for all to see. He advertised his support for the legitimacy of the pharaohs right to rule even after he. Weni, had died. So, he's one of the great dead, as we call them.

And I forgot to say before, but two of his aunts married King Teti, so he was intimately connected with the royal family and he was not a nobody.

Then we found broken pieces from his northeast corner pillar lying in the sand. One of my jobs, one of my many jobs, is to put them together. So, we start putting them together. And you can see his name there, Weni. The hare, N for water, I the reed, the [unintelligible 21:09]. We start fitting them together before the digital age of bits of paper and having to deal with things that were sliding off. Always work closely with conservators, they’re amazing people. And how many bits of stone. The remains of his southeast corner pillar. And amazingly, his almost intact southwest corner pillar. Getting it home to the house was fairly interesting. Downhill.

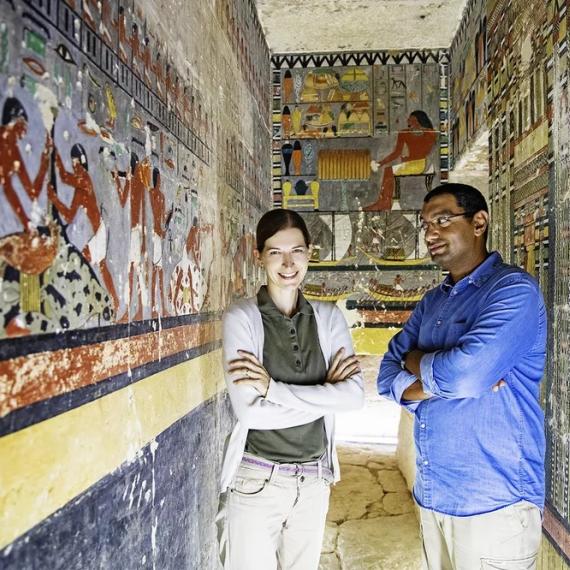

And then in the Cairo Museum I found two more bits of unprovenanced, decorated slabs that belonged in the, well, I identified them as belonging to the chapel. When we got them there, thank God they fitted. And so, we started putting things together. We collected material from Cairo, from our own storerooms in Abydos and from the storerooms in Sohag. At [unintelligible 22:12]. And we brought it all in with and laid it out in a room that had no ventilation. You see the fans. And the heat last year was 44 degrees Celsius. So, it was interestingly difficult!

And we started putting things together. And that's my assistant, Rasha. Sorry, I've scrubbed out her face. Literally holding stones as they were put into place and we hadn't done this before. We hadn't had everything in one place. We had drawn pictures. We tried to do it digitally. So, we didn't really know whether this was going to work but it did work. Tiny little stones, big stones.

And conservators and epigraphers working together. And this, that I'd found years ago, wondering what on Earth it was, but thinking it might be something to do with the back end of a hare, with a little tail sticking up. And this that I thought might be an ear and Rasha’s eagle eyes turned it upside down. It became the bottom of a hare. So, you can see there's the end, there's his front legs, there's his body, there's a leg, there's a leg, there’s a tail, there’s his backside. I hadn't thought of turning it the other way up, had I? And she put it on a piece of paper and held it against the stone and jumping out at us was a head and a foot, so that all got put back together.

So, you work with massive blocks of stone that you have to have lots of big blokes carrying round for you. Or tiny bits of stone that you can do yourself. And that was the local crew that we worked with. And that's Rasha, that's Dr. Mohammed Yazid, and this is Mr. Alah, the director of the museum that we were in.

And we're setting up and I can't show you this because we're in the process of publishing it, but we're setting up his chapel, we're rebuilding it in, as an, as a permanent exhibition in the Sohag Museum. And this is the bloke. Yes. Who carries the stone. And, that's the museum at Sohag. It's built in the form of a mastaba. Okay. So, Weni is finally going to have his tomb chapel put back together as a permanent exhibition here.

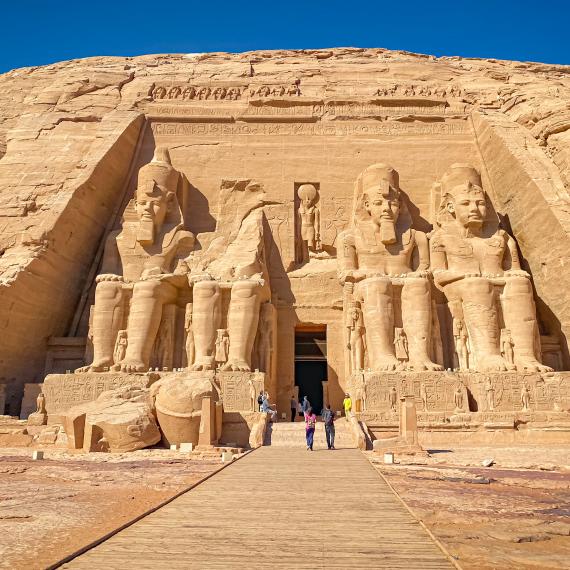

And that is Abydos, as you see there, and that's our dig house there. And over there, the Germans. And looking back towards the gap in the Gebel, the high Gebel, the desert. And that is where the entrance to the underworld is. And so, at night, when the wind blows, it's quite eerie because that's where you get the spirits coming up and going back. That's the west behind those hills.

Thank you.

More Episodes

John Mirosevich explores the varied history of Thonis-Heracleion, Egypt’s greatest Mediterranean port for 400 years.

Listen to Hon Dr Anne Aly MP who joined us at Afterlife Bar for a presentation on the Discoveries of Ancient Egypt exhibition.

Join committee members of The Ancient Egypt Society of WA Inc for a unique opportunity to dig deeper into Egyptology.

Dean Kubank revisits the Temples of Nubia and the enchanting Temple of Isis at Philae.

Celestial Timekeeping in Ancient Egypt - Discover how Ancient Egyptians used the heliacal rising and setting of stars to construct their star clocks and civil calendar.

The life of the average Egyptian could sometimes be precarious and short. Broken bones, infections, and arthritis were all common among the general population.

Discover the story of the pharaoh Djedkare, his family and courtiers, and take advantage of the rare opportunity to hear from visiting international Egyptologist Dr. Hana Vymazalová of Charles University, Prague.

Discover the story of the pharaoh Djedkare, his family and courtiers, and take advantage of the rare opportunity to hear from visiting international Egyptologist Dr. Mohamed Megahed of Charles University, Prague.

Discover Egypt’s ancient legends of creation, death and resurrection. Tales of Ra, Osiris, Isis and Horus will unlock the meanings of the art, religion and funerary practices of ancient Egypt.

How, when and why was mummification invented? The answers may surprise you.

Ancient Egyptian Astronomy Unraveled - Discover how the Ancient Egyptians used their knowledge of the sky to design and position their temples, statues, and roads.

As part of our evening Afterlife Bar series at WA Museum Boola Bardip, we welcome a series of speakers to dive deeper into Egypt. Join us this week as we hear from Dean Kubank on Temples and Tombs.

Renowned expert in ancient Egyptian history Daniel Soliman delivered a fascinating talk, as we celebrated the launch of the WA Museum Boola Bardip's Discovering Ancient Egypt exhibition.