Egyptology Q&A Panel with Dean Kubank, Tina Johnson & Jasmine Day

What would you most like to know about ancient Egypt? Has Discovering Ancient Egypt exhibition left you wondering about something? Here is your chance to hear from a panel of enthusiasts . Their specialisms range from temples, tombs and hieroglyphs to religion, mummification and magic. Join committee members of The Ancient Egypt Society of WA Inc for a unique opportunity to dig deeper into Egyptology. Featuring Dean Kubank, temple explorer; Tina Johnson, hieroglyph decoder; and Dr Jasmine Day, mummy expert and AESWA President.

-

Episode transcript

22nd September 2023

Egyptology Q&A Panel with Dean Kubank, Tina Johnson & Dr Jasmine Day

_________________________________________________________________________________

Event MC:

Good evening everybody and welcome to the West Australian Museum Boola Bardip and the Discovering Ancient Egypt exhibition. Before we get started with our guest speakers for this evening, I would just like to take a moment to acknowledge the lands on which we are gathered on and learning here today, the lands of the Whadjuk people of the Nyoongar nation and pay our respects to their elders past and present.

So today we have a panel discussion from the committee members of the Ancient Egypt Society of Western Australia. I'll let them introduce themselves, but it's a Q&A. You can ask questions. They'll do their very best to answer. They're amazing at answering so please make them feel welcome.

[applause]

Dr Jasmine Day:

Okay. Thank you so very much for coming tonight and sharing your Friday with us. So, we are from the committee of the Ancient Egypt Society of WA. This is Dean Kubank our resident expert on temples. And this is our hieroglyph professional. This is Tina Johnson. And I'm Dr. Jasmine Day, the president of the Society. So welcome on our behalf.

We do have some fliers that you're welcome to pick up on your way out. We are a public group. You're welcome to join us. We have a talk every, first Wednesday of each month except January. A lecture or a video or some kind of activity at Citywest Lottery's House at 7 to 9 p.m. on the first Wednesday of most months of the year. And we're a public group anyone can join. If you're interested in ancient Egypt, you don't need to be any particular level of knowledge. You don't necessarily need to have even been to Egypt.

By the way, we are thinking of planning a trip to Egypt in a couple of years, just in case you're interested. And we have a very expert guide who may be able to take us. So, if you're interested, please do get in touch. And we've got a website and all the details of that are on our flyer, so please do pick up a flier on your way out, if that sounds interesting.

So tonight, what we're going to do is offer you the answer to every question about ancient Egypt that you always wondered but were too afraid to ask. Or maybe not. And the idea is that we’re sort of driven by your questions. But if it does go a little bit quiet, we've got some topics, we’ve got all sorts of images that we can choose from to show you, to talk about. So maybe what I'll do is I'll start by asking, does anyone have a specific question? If not, I'll ask if there's any topics of general interest. But first of all, does anybody have a question to start us off with questions?

Here we go. Here we go. There will be roving microphone all evening. I'll sit down and be ready.

Audience member 1:

It's not a specific question, I suppose, but I'd love to hear your, your thoughts on the ethics of researching dead people or people of colour and how you go about that. Yeah.

JD:

Okay. What I'm going to do, if you'll excuse me, and this we’ll have to do during the evening, just switch between views because you're asking as I understand it, about our views on such things as this? Is it the ethics of displaying Egyptian mummies, for example? Okay. I don't know if you're aware, but I'm one of the world experts on that subject as a matter of fact.

[audience laughter]

And seriously though, I am. I published a paper in 2014 on that subject, which is on my academia.edu page called ‘Thinking Makes It So - Reflections on the Ethics of Displaying Egyptian Mummies’. It's a big subject. I could just do a talk just on that. So, I'm racing to think because I don't have a slide specifically on that. But do I have a slide of mummies in general that I could show you? Okay, here we go.

All right. So, the background, very, very basic background is that mummies, as you’re probably aware, were widely robbed in ancient Egypt for their valuables and over the course of thousands of years. And then after the Arab people came to Egypt in about six or the 640’s AD, they sort of live alongside the ruins of this ancient previous civilization.

And I have heard stories that sometimes some people would take the mummies from the tombs, the ones that had already been robbed perhaps, and even burn them for fuel, or certainly they did live in many of the tombs. So, when the Europeans came in the 19th century and into the 20th century, of course, there was a big trade in antiquities. That was largely curtailed, but not entirely by legislation brought in in the 1980s by UNESCO. But in the meantime, many, many things were taken from Egypt, including mummies. Some of it was taken illegally, some of it was taken legally with the consent of the government. And so, there is a whole issue overlying the ethics of mummies to do with the ethics of simply things being outside of Egypt. And it's very, very complicated. It's not true to say everything is stolen. That's actually quite untrue. But that complicates things further.

With mummies I've done a lot of research in museums. I believe I'm the only person in the world who's done extensive research on how people react to Egyptian mummies - children as well as adults in the United States and Britain and Australia. And I found that reactions to mummies are often these days of disbelief that they’re real or that the bodies inside are real. Partly because people aren't used to being exposed to dead bodies today anymore.

Also, because the images you see of mummies in things like modern films are highly distorted and exaggerated and mummies (and this is one thing I do have an ethical issue with), mummies have largely been represented in modern Western popular culture as evil. If you tried doing that to any sacred figures from anybody else's culture, you probably won't get along so well. It's literally over their dead bodies that we represent them as evil. And I have argued based on my observations, that people's objections to the display of Egyptian mummies are only sometimes out of real understanding and concern for Egyptian beliefs. And a lot of it is more to do with coming from fear of mummies based on them being monsters in popular culture. So, a lot of objections to display are actually sort of off the beam as you were. It's not, not really relevant.

What do the Egyptians believe? Did they believe that bodies should be displayed? They certainly wouldn't have expected them to be where they are right now. Some people think that we ought to, you know, just pack them all up and put them back. It simply cannot be done. The money it would take to just conserve them and prepare them to be returned to Egypt, and the money it would take for all those extra mummies, as it were, to be brought back to Egypt would break the economies of the world. It would be just impossible logistically to do it.

Also, the Egyptians generally don't want these things back. There are very few things that they've actually specifically asked to have back. Mostly the things they’ve asked for, are things like the Rosetta Stone or the Berlin head of Nefertiti, which is based on more to do with them being iconic rather than being stolen. Because many of these things were taken before there was legislation even so, how stolen is stolen. It's complicated.

As to what the ancient Egyptians believed about their bodies, as I said, I don't think they could have anticipated what we're doing today. But on the other hand, there is a case where many royal mummies were taken to save them from the tomb robbers during a later period, centuries after they were buried but still during the later period of ancient Egypt. And they were reburied in a single tomb. And these are known as the Deir el-Bahari cache Mummies, the Royal Mummies, including people like Ramses II and Seti I. And those mummies were stripped and studied because that was all they could do back then before the invention of x-rays to study them. The coming of technology now means that we don't have to unwrap mummies anymore and be disruptive or arguably disrespectful. So, you can see that a rare case like this in which a mummy is still completely covered, is going to be now left that way. So, don't walk into a museum and say, why can't we unwrap them? You can't. And they'll get kids saying, why can't we just get more mummies from Egypt? You can't. That's not legal anymore. We've got what we've got and we won't be getting more. And as I said, with the Deir el-Bahari cache, it shows that in extraordinary circumstances, even some of the Egyptians understood that you can't just leave a mummy in the same tomb forever because someone's going to come and steal it. And that is sadly as true today as it is in the past. And people are still stealing mummies and still trying to smuggle them out of the country. There have been some notorious cases of suitcases full of human parts and all sorts of things.

So, what we do is we try to conserve the mummies we have, not unwrap them any further. There is a current debate about whether to display mummies at all or not, and there is no museum consensus on the subject. Some museums have put their mummies away altogether. Others have left them on display unwrapped. Some have partly covered them up again. A bit consistent with what the Egyptians are doing, covering them from neck to knee, for example, like they do in the Cairo Museum with the royal mummies and the mummy of Tutankhamen, which is now on display. I think they took him out of his coffin really in desperation to get tourists to come back again after everything that's happened.

So, it's very much up in the air. There is no single school of thought on this. There is no single resolution of museums on this. It's currently something being debated in the literature about that, and I'll be happy to discuss that with you further, because that really is, as you can see, a massive subject. But thank you for your question.

Dean Kubank:

I was just going to add times have changed in terms of respect for mummies. In the past, especially in the 19th century, the British gentry were well known for having mummy unwrapping evenings. So, they’d invite holiday guests, and they’d make a special night of unwrapping a mummy. There was mummies taken in large numbers to the US and they were used for fuel in steam engines and trains. So that's how respectful, disrespectful people were towards mummies in times gone by.

JD:

Yeah, we talk about today how you know, in the past people damaged the environment and used fossil fuels and so on and we're being left to pick up the bag with all those issues. In the same way in the past, the Victorians, as you said Dean, seemed to think that the supply of mummies would ever never end (wrong) and think that all mummies were more or less the same as each other so you can throw a few out and it doesn't matter (wrong). And of course, they kind of forgot that they were people somewhere along the way. But then those were people who maybe were more exposed to death and also being colonialists they were affected by the feeling of being superior to ancient people and superior to foreign people.

So, all of that woven together made for a situation of massive destruction of mummies. As you say, mummies as entertainment.

Okay. Any further questions? The next question, or perhaps you might instead rather, rather than a question, you might have a topic you'd like to hear about? Yes

Audience member 2:

Hello. I'm just wondering what the significance of blue is for ancient Egypt?

JD:

Ah, the color blue? Have any comments on blue? [inaudible comments from other panelists] The Nile River? Yes. Lapis lazuli, in fact, right here in front of us is the mask of Tutankhamen, which features a great deal of lapis lazuli, which the Egyptians imported via long, long trade routes all the way from Afghanistan. Blue, as Dean says, is the color of the sky. It's the color of the Nile. And it has all those sacred associations with the river that sustains life in Egypt since antiquity. And with the sky where many of the gods live. So, it is a very powerful color.

I do believe that - I don’t know about lapis lazuli, but I know green, which is similar to blue in terms of the way that many colors treat them, those colors. I know green is the color of the stone malachite that was ground up to make some of the eye paints that they used as well. Do you know if they used lapis lazuli in making eye paints? I know they used it in paint. [inaudible comments from other panelists] It's more for, it is for jewelry, that's right.

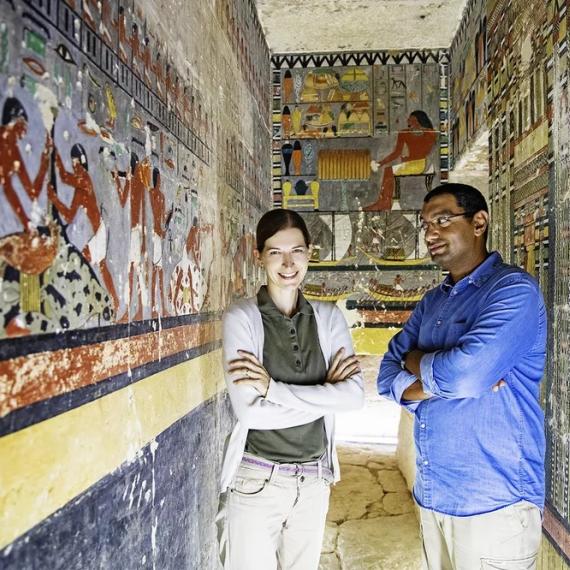

Yes, what I'm going to do is jump through my PowerPoint show like this and I can choose relevant images of things. I'm just trying to think of something I've got that's blue. I'm not sure. But certainly, you can see blue sometimes in in the artwork in the tomb paintings. Well, here we are. This the Tomb of Seti I and although it's got a lot of damage and it's sort of in the dark and it's lit there, what comes through is being a bit black here is in fact blue. And this would have had a malachite in it, I think, to make that blue color in the paint and you see it being used in a royal context on Seti, the pharaoh Seti on the right-hand side there. And on the left-hand side, you see it being used on the god Horus. And of course, he is a god of the sky. He's a Falcon and also the God of Kingship, the God of the Pharaoh, meeting his counterpart on Earth and as a God, a God of the sky, he has blue in his his mane there, that you see, and in the jewelry as well.

Audience member 3:

I mean, it's been a lot of discussion about how the pyramids in the Sphinx were built. Is there any evidence to show who built them?

JD:

I thought you would say that. Okay. And I'm glad I brought along an extra PowerPoint show.

DK:

Can’t say we were not well prepared!

JD:

We were well prepared. Yes. Okay, so maybe all three of us will kind of tackle this question. The first thing I have to say is that we know that some of the fallacies about the pyramids being built were fallacies. They were definitely not built by slaves. Just think about it. If you've got one person in charge of a team of 100 people or 200 people and he's got a whip and they've got nothing but their bare hands, well, they do outnumber him. So, chances are not built by slaves. Absolutely not.

So, we've found villages of the workers who built the pyramids and inscriptions that they or their team leaders wrote. It would appear that they actually competed with each other to see who could put the most blocks down in a day. It was like a race. And who's to say they didn't even bet on it? And they would give themselves team names like what was it, Team Khufu or something like that? And I think there's a block in the Great Pyramid that's actually still got an inscription on it from one of those teams. That's right. But all sorts of theories have been advanced as to how they did it. First of all, we can rule out impossible things like anti-gravity devices. We can rule out things that they didn't, hadn't invented at that point in history like cement. So, no.

This is just a borrowed PowerPoint show. So, I won't go through all of this. It does slide down the bottom there that they might work for 20 seasons, as in 20 years, you know, once a year for a season, working on the pyramids. They would work on the pyramids during the season when the Nile flooded and it covered the fields so they couldn't work on their fields. And that's when they would be drawn up, wasn't it, by a system of the government made them come and do it I think? They dragooned people to come and do it.

DK:

But also, people thought it was a great privilege to come and worked on pharaoh's monuments.

JD:

That's right. That's right. They yes, they thought they were going to get something out of it. And the medical help available to people, medical support would not normally have been available to people of that lower social class. But if you're working on the pyramid and you broke your arm or got a cut, there would be professional doctors there to help you. Okay, so I'm just passing through a couple of slides here. Okay. The Great Pyramid of Giza, that is not the Great Pyramid behind that. That is the second pyramid, isn't it? There are three pyramids built by Khufu - that's the greatest, the Great Pyramid, the biggest one, Khufu, Khafre and Menkaure. But to the Greeks, they were called Cheops, Chephren and Mykerinus. That's why you get two sets of names.

Tina Johnson:

Just saying that looks like Khafre’s.

JD:

It looks like Khafre’s. Yes, it is. Mastaba tombs, I might talk about this a little further, but they were basically flat shape tomb, and I may come back to this flat shape tomb. But by stacking them on top of each other, they created the step pyramid, which was the first pyramid, but not the first true pyramid. It was the architect Imhotep, who came up with this idea. Sorry about the writing on this. I'm just skipping through this quickly, but to answer your question, building the pyramid, they would use limestone and granite to do that with. And I think the tools they had were only copper, weren’t they?

DK:

Yeah, they were very basic elementary tools and they had to replace them regularly. They wore out very quickly.

JD:

That's right. And also, there was a guy counting them to make sure you didn't nick them as well. And they would use things like string to, to get the ground level. To simple methods of leveling the ground, which isn't really addressed here.

They would break the blocks of stone out. This is a simple old technique. We find evidence for it everywhere. If you look very closely at the bottom left picture, if you can see it, just where they’re heaving that block out, there are some little notches in the ground. And on the top left you can see what made those notches. They carved notches into which they would put pieces of wood and then wet the pieces of wood. And the wet wood would expand, of course, and then crack the stone along the line. And you can go to ancient quarries in Egypt today and see all these notches in vertical parts where the stone has been broken away for an ancient block that was taken somewhere and there're still these notches all in place. So that's another piece of evidence that we have. Ancient Egyptian quarries, notably the granite quarry of Aswan. Granite, pink and black granite was very beautiful, more so than limestone. Limestone was used as a core or a filler, but they would use something like what we now call alabaster, or they would use granite, pink, granite to face things with.

And how they would carry it along in boats. We know that they've got images there, bottom left that's been copied from a tomb painting or possibly seen in the temple. I think it would probably be from a tomb. Showing men on the shore pulling a boat along, although it depends on which direction it was going in, it might be under sail, going along, carrying stone in these boats. One of the great things about the Egyptians was they left a lot of evidence of how they did things on tomb walls. It's like a, you know, photos from my family photo album. And I went down, and I was on the team that drew these blocks along. So, here's some pictures of us pulling the blocks along. So, a lot of this comes from tombs.

Now, the main thing I wanted to mention in the bottom right there, it shows you building a ramp. Now, that ramp actually, to me, this is only an artist impression. It looks a bit a bit steep. And I think as they’ve shown, if these ramps were not too steep and they were just the right inclination for people to pull, pull the stones up, they would have stretched right down into the Nile. So, it couldn't work. So, we think actually that they went in loops around the pyramid. Do you agree with that theory?

DK:

Yep. Yep.

JD:

I think it's widely believed now the circuit around the pyramid on the ramp.

DK:

Yeah. The inside was quite rough. I didn't worry about that too much. It was the, the outer blocks that they spent all their time making sure that they were exact in size and they were very smooth and shapely. And of course, when the pyramid was finished, the whole surface was, had a white plaster cast across it so that it was stunning in the sunshine it used to light up.

JD:

Yes, the pyramids used to virtually glow in the sun. They were all white. And we see now sort of nude pyramids that have been stripped of all that very nice fancy casing stone, which was taken away in later antiquity to build other monuments and later on still to build mosques and so on. So, remember that the pyramids, if they look a bit rough, well, they used to look very smooth.

And they used to have a big capstone called a pyramidion on the top as well. In fact, there is a pyramidion from a mini pyramid. They stopped building these big, big, expensive monuments after the Old Kingdom, the oldest period of ancient Egypt. They didn't forget about pyramids, though. It became very symbolic in the culture so that centuries later in the New Kingdom - think Tutankhamen, Ramses II, New Kingdom, they still remembered pyramids and would build a mini pyramid on top of some fancy types of private tombs. And then that would have a little pyramidion block, a pyramid shaped single block that goes on the top. And when you go to the exhibition, the first thing you see is you go in the door. On your left is a pyramidion from a private tomb from the New Kingdom. So, there you go.

And of course, they didn't have wheels because if you use wheels on sand, what happens? They sink. Who needs wheels? So, they use sleds or rollers. Rollers of wood. But they didn't have a lot of wood in ancient Egypt. Wood was quite precious. So, there you go. There is the theory of going around and around the pyramid. And then they would decorate it from the top down as they dismantled the ramps and went from the top down to the bottom. So, yeah, okay. And that's what they look like in the end. Okay.

TJ:

Sorry. Can you hear me? Yeah. I just want to add that like Dean was saying, the earlier pyramids had, mostly they focused on the outside of the pyramid. However, from the sixth dynasty, um, starting with King Unas. He actually put hieroglyphs, wrote hieroglyphs within his tomb, and he actually the hieroglyphs within King Unas’s tomb. If Jasmine can bring up this slide, which will show you. These became known as the pyramid texts. And the pyramid texts consisted of around 700 spells and magic incantations to help protect the king's ‘ba’ and the king's ‘ka’ through the afterlife. The last, the latest pyramid to use it, to use pyramid texts was in the eighth dynasty and that of King Ibi.

So, once these pyramid texts were used, they were mainly used only during the Old Kingdom for the royal family and later on within the Middle Kingdom as, as it came through, nobles became a lot more powerful. And they said, hey, just a minute, you know, we want tombs as well. They developed something else called coffin text, but they were based on the pyramid texts, but expanded to actually include the references to the nobles. And then from there it went on to the Book of the Dead. And you'll actually see in the exhibition, although you won't see the pyramid texts in the exhibition, there are some beautiful coffins with coffin texts on them. And the, there’s some beautiful examples of the Book of the Dead as well.

Audience member 4:

Hi Dr Day, this is probably a question mainly for you.

JD:

Okay.

Audience member 4:

With the process of mummification and ultimately the dessication of the corpse, any indication as to how long decomposition was warded off until that dessication process started? I mean, how, how long and in what condition would a recently deceased and mummified body maintain its, its lifelike condition?

JD:

Okay, I think you're asking once a person has been mummified, how long will that body stay mummified for? No, no?

Audience member 4:

How long will the, would the lifelike representation, the decomposition of the corpse be warded off before they started to take on that, that appearance of mummification. Do we know?

JD:

Okay. Yes. Yeah, I think this there's several things coming in here. One is how quickly does a human corpse decay under normal conditions and then what do we mean by normal conditions? Because a place like Egypt and other hot countries, the process of decay speeds up and within just a couple of days. Hence, the tradition that, for example, some Muslim people have in that part of the world of getting a body buried as quickly as possible. Why? Well, just try not burying it that quickly and see what happens. It's not pleasant. So, if you're simply doing inhumation, burying a body without mummification, you've got to get it under the ground within I think the rule is about three days, I think is the religious tradition. Correct me if I'm wrong.

But we have some examples of people who were or one mummy I can think of, a mummy of a man called Horemkenesi, who was a tomb inspector, who went around looking at tombs and writing his signature in hieroglyphs on the wall, saying, you know, I've checked this tomb out, it hasn't been robbed. It's all good. And he signed his name, so we've got many examples of his signature around places like the Valley of the Kings.

But he happened to die one day when he was out wandering, he probably had a heart attack, and he wasn't discovered for several days. When he was discovered, he was not in a good shape, but they took him off to the embalmers, so he was mummified. But in the meantime, he didn't quite attain the great appearance that a lot of mummies did because he got to the embalmers table too late. And in the meantime, his eyes, of course, had disintegrated because they're made largely of water and his brain had melted and run out through his ear. So, the embalmers didn't bother doing the brain removal stage. They just went, what a mess. Let's leave it. And they didn't they didn't take the brain out because there was no brain. And also, he had some insect damage starting to happen to some of the body as well. So, yes, he was in an unpleasant state by the time he got to the embalmers.

But that is actually quite a big matter. We know from some of the classical writers like Herodotus that some bodies, some people died out in remote areas where there were no mummification facilities, and the bodies were pretty on the nose by the time they reached the embalming table. So that ideally was not supposed to happen. But you would therefore ideally have to get the body to the embalmers within, I should think a day or so ideally of the person actually dying. They would rush to get that body off to the embalmers. Is that the sort of thing you're driving at? Yeah.

[inaudible comment from audience]

Yes. Well, once a person was embalmed, of course, they maintained as lifelike an appearance as one can look when embalmed by that method. You're going to look a lot thinner, your skin, irrespective of your color of skin during life is going to be a lot darker. It's going to go that coffee brown color or darker, maybe a sort of blackish brown. So, a pale person like me, if mummified, would end up looking like that. But it did preserve about as lifelike an appearance as it could.

Did it stay looking that way? Under optimal conditions, yes. So, a mummy, if left undisturbed, which virtually never happened, would stay preserved indefinitely. And we have many examples of mummies brought to play at places like Europe where the temperature and the humidity is very different. And if kept indoors in fairly stable environment, they would stay preserved. But we have had several instances going back to the mid-20th century and the early 20th century of mummies that had not been stored well. They’d been kept in musty attics or basement somewhere or kept in storage in Europe or the United States, and they started to rot. Actually, no, it's Britain and the United States. Two instances of a children's mummies, one in the United States that was given a so-called Christian burial. Buried in a burial ground and one in the about the 1970s or so at a museum, I think in Exeter in the UK, that was starting to pong and they decided to have it cremated. Not everybody was happy about that, but that happened.

So again, there's all these different stories about the many conditions that affect how quickly a body decays, whether people intercept that process soon enough to do an adequate mummification, and the conditions in which a mummy is both prepared and stored in the long term over centuries and centuries. Yes, many, many variables.

Audience member 5:

So, on that same topic, I was wondering has it been put forward or proposed (it's a bit morbid, but I guess it's mummification) the idea of trying to replicate the process for scientific investigation.

JD:

Yes, absolutely. And of all things, I think actually left that, that's one thing I left out of my PowerPoint show. Oh boy. Yes, the answer is yes. So, in 1990, something Bob Brier, in the mid-1990s in the United States, Professor Bob Brier did a Discovery Channel documentary in which he took a human body of a man donated to science, but not for any specific cause. And he mummified that using as much as was then known of Egyptian mummification methods. And overall, it was a success and it worked. The mummy has been (we don't know his real name, so he's just been called ‘Mummab’) and he's on permanent display at the Natural World, sorry, The Museum of Man in San Diego. He has been repeatedly checked out. They've done biopsies on him and found that there's been stabilization. Again, kept in a regular environment in a museum setting with control of humidity and such. And he has remained preserved with no aerobic or anaerobic bacteria developing.

Some of the major discoveries of the Bob Brier process were that the black, black stone that Herodotus, the historian, a Greek historian, describing mummification of the Egyptians, he refers to a black stone being used to cut the body, to remove the organs from inside. And we need to take the organs out because that's where a lot of the moisture is that speeds the process of decay. So that's the first step, you take the organs out, evisceration. Now Bob was trying to do that with a copper tool an ancient Egyptian copper tool. Turns out that this tool, which was found, I think in some tombs, we found them, it was more like a shaving tool. It wasn't sharp enough to cut that much flesh but interpreting black stone to mean not just a stone from, you know, Sudan, where the African people live, a black stone, but specifically to mean a black colored stone does it mean obsidian? The Egyptians had obsidian. Well, they cut a set of obsidian tools and cut the flesh like butter, said Bob. So that worked.

Another thing they discovered was the speed with which you will, the point at which you intercept the body stiffening as it's drying out with the natron salt drying the body out. You have to position the arms into the royal posture or whichever posture you want, depending if it's a man or woman and what class of period of society. And you have to do that before it gets so stiff that you can't bend the arms. That's why Mummab has arms that are like this, just like this. Because they couldn't bend them at the elbows any further they would have broken them off otherwise. So they found it starts like soft leather but it gradually hardens and hardens. And taking all the moisture out is actually not what you want to do. You want to take most of it out, get the body positioned, then let the drying continue.

The third thing I discovered in Bob's experiment in the nineties was removal of the brain. They found that you had to stir it like porridge until it turns into a liquid and could be poured out through the nose. This mummy movie thing where they say, they used to swirl it on a stick and pull it out through the nose. What did they have endoscopes back then? Could they see what they were doing? Of course, they couldn't see, and they can't cut it up into pieces and pull the pieces out and hook them and locate them all. They can't see what they're doing, they’re flying blind. So, they just stirred it like a bowl of porridge and out it poured. Which explains why we don't have a canopic jar with a brain in it. As opposed to other organs in Canopic jars. So that's one of the mistakes and myths you see in a lot of Hollywood films. You're getting the stages of mummification right.

That was the big experiment. But then in more recent times. When was it now? About 15 years ago, ten years ago. You may or may not have seen a documentary on the telly called ‘Mummifying Alan’. There was, it was on the ABC, rather graphic, but fascinating science. It was long debated whether Herodotus was referring to using dry natron salt to dry the body up, which clearly can work. Or was he referring to wet natron in solution, a bath of natron. Experiments with small animals, trying to mummify them with wet natron at the Manchester Museum in the 1980s were failures.

But now, I’m just trying to remember his name. It's gone out of my head. A colleague of mine in the UK decided that he was going to do another experiment using wet natron on a body donated to science. And he used the body of a man named Alan Billis, who was a taxi driver dying of cancer. He approved for his body to be mummified. He actually put a call out, the professor put a call out saying ‘who wants to be mummified?’ and all these people came and said, ‘I want to be a mummy’. Wow! But he chose Alan. I guess Alan died first, maybe. And so, with his consent, because it's all about ethics, he made him into this mummy. And in short, put him in a big natron bath and, and got the timing of everything right and the blood sort of absorbed out into the natron and all went red. And we think this might have been a symbolic part of the process. Anyway, it all worked.

So, both wet and dry natron in the right hands with the right timing and experience, which they obviously had. - both of them can work. And now that's thrown everything open. What we thought we knew about mummification is not wrong, but it's up in the air. Which technique was used? Were they both used? Was one used, then they switched to the other? Was the wet natron only for royalty? We don't know. There's still a lot to find out. But it all started when the professor looked at the bones of the royal mummies and said the natron had sunken in right through into their bones. That wouldn't happen if it was dry salt, dry natron. I think he said it was a natron bath. That means that people like Ramses II were preserved in a bath of natron. Interesting. It's hard to answer that question in a soundbite, but it's, there's a lot to know. As you can say, it's complicated. I think we have another question. I think we got two questions on the, on the right.

Audience member 6:

So, everyone’s heard about the pyramids, at least I hope they have, but have they heard about the great labyrinth that was at Hawara. And the fact that Herodotus, I think, described it as more spectacular than the pyramids.

JD:

The labyrinth at Hawara?

Audience member 6:

Yeah.

JD:

Yes. Now people ask me about things I haven't got a picture of tonight and I’ve brought a whole…, but yeah. The Labyrinth of Hawara. Do you know anything about the one? You know about that one? This is Herodotus. Yeah.

TJ:

I can't remember a great deal, but we've certainly been. And it was pretty spectacular from what I remember. Yeah.

JD:

What was Herodotus referring to? Remains that are no longer standing, I think. Was he mixed up when he said it was a labyrinth? It wasn't a labyrinth. It was what, a temple complex?

TJ:

Yeah.

JD:

And there were only ruins left now.

TJ:

I think that was. That was the case, yes.

JD:

Yeah, there have been cases (and not just this one in Egypt), Memphis, for example, where there were mighty, mighty temples. Bubastis as well. Mighty temples. And you go there now, and it looks like a bomb’s gone off. There's nearly nothing there. You see broken stones and inscriptions and things, and a lot of it's gone. And you think, well, where did it go? And the answer is often, but, you know, depending which sort we're talking about, there may in some instances have been earthquakes or other collapses. And then, of course, the stone robbers have done their job. Ah look, nobody's looking after this big Lego, Lego set. I'll just take a few bits for my own. And stone robbing was just rife everywhere.

So, when Herodotus said that Hawara, which is a site up in the delta of the Nile up in the north, had a spectacular labyrinth, we don't think it was a labyrinth, as in Greek mythology, the Minotaur, the labyrinth. I think rather it was just a very big, possibly circuitously designed building, i.e. a great big temple. And we do find the remains of sort of old blocks there. There is a very old pyramid there. I think it’s the Middle Kingdom at Hawara, which I've been into, and that's again quite ruined. But it's got a lot of passages on the inside of that one.

But yes, it's amazing how sometimes we get these glimpses into what has not survived from the ancient world. We're so used to seeing pictures of the pyramids and the Sphinx and Karnak Temple. And it begs the question, what are we missing now? What did not make it into our era? If you think of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, the pyramids are the only one left standing.

If you look at reconstructions based on science and archeological remains of the other ones, you think that would have been incredible. I would, you know, if I could vote one thing back into existence other than Egyptian things, I would vote for the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus because that was spectacular. I mean, the horse's heads just from the horse group at the top of that were as long as this table. That's the head of one horse on the top of a four-horse sculpture then a chariot on the top of the thing. Just imagine the scale.

So, if people were building in the scale back then, who knows how big this labyrinth could have been? And there is a debate whether Herodotus actually went to Egypt or whether he was using secondhand information from others who'd been there or come from there. And I think I tend to actually favor the latter theory. Which was more widely believed once upon a time that he didn't actually go to Egypt, but he had some inside sources. Because some of his information is guesswork and just wrong. I mean, really, really wrong. And other things are stunningly accurate, like his description of mummification. So, I think he got to possibly bribe an embalmer and speak to somebody or something like that.

And yet, on the other hand, if he didn't go there, then he, that would explain why he didn't know some of the things. So, yes, labyrinth, I would say he's using his guesswork maybe to describe something he hasn't actually seen. But that's just a theory.

TJ:

I just want to add many of the Middle Kingdom pharaohs are actually have their pyramids, many in ruins between Hawara and Dahshur. And the difference between the, the other pyramids and these particular ones, they were often built with mud brick or on sand bases. And basically, they just didn't stand up to, to the environment.

So, Amenemhat and Senusret, they have their pyramids around and about there. I think the Black Pyramid of Senusret is pretty good. It's still, still around. You've been?

[inaudible reply from audience]

You haven't been. Have you seen any pictures?

Audience member 6:

Yeah, I've seen pictures, but just online. So.

TJ:

Yeah. Yeah.

JD:

Not every tour will take you to those places. I went with the Egypt Exploration Society, so I suppose more academic trips will take you to these, these other sites. Yeah.

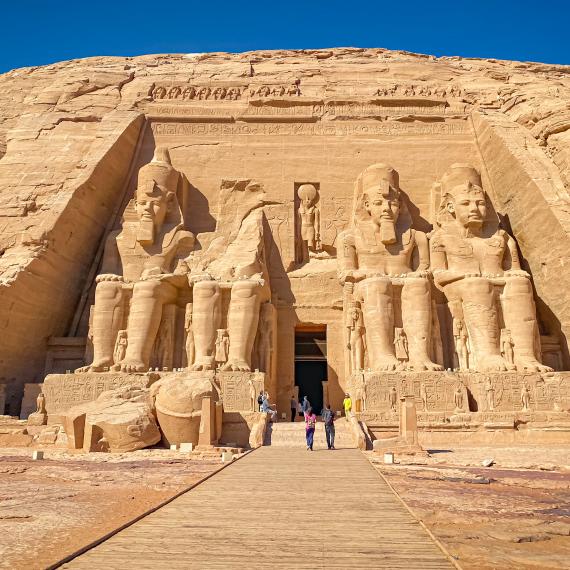

DK:

If you want to see a labyrinth, go to Karnak Temple and the size of the temple is quite astounding when you view the model. That one. So, that’s sort of built over a period of 2000 years by at least 30 different pharaohs. It was, if you were considered to be a pharaoh of worth your salt, you would leave your mark in Karnak Temple. So, as you can see, it's quite a extremely large complex. And at one stage there was 80,000 people employed in the temple and the surrounds. So, that's a magnificent place to visit. You can see the size of the columns. So, it's certainly a significant building.

JD:

And the statue of Amun there, sort of toward the bottom, left of the middle - that's over life size, isn't it?

DK:

Yes, absolutely.

JD:

It's massive columns. I think what really struck Herodotus, whether or not he went to Egypt, was the size of things. I think it struck a lot of people, actually. You can see some people there in the left-hand corner, and then you see a statue of Ramesses. I mean, that's scale for you.

Audience member 7:

Thank you. I understand that there are a lot of pyramids in Ethiopia, I think. And I'm just wondering, did the Egyptians get the idea off the Ethiopians or are they more modern than the Egyptian’s pyramids?

JD:

You're talking about the pyramids, which were the tombs of the kings and the queens of the empire of Kush. To what the Egyptians called Kush or modern or Nubia, which is more of a geographic region. Today it's Sudan, or not exactly the same borders as in antiquity, but Sudan, south of Egypt. And what you were suggesting later in your question is correct. Though, that empire followed Egypt. It was, it coincided with the later part of ancient Egypt, and they were influenced by Egyptian culture. So, they had these kind of, they're interesting tombs because they look like a mash up of Egyptian tombs from different periods.

They're half pyramids, half temple, like somebody took an Old Kingdom pyramid and a New Kingdom temple and smooshed them up together and designed a new type of tomb. So those are fairly unique to that part. So, it was known as the Kingdom of Meroë. Kingdom of Meroë. But having based some aspects of their culture on ancient Egypt, they were by no means a carbon copy.

Although they did worship some Egyptian gods such as Amun, in particular as in Tut Ankh Amun, the God Amun. He was very popular during the New Kingdom and he influenced the Nubians, but they had a lot of unique aspects of their culture. So, they were a black African culture, and they had some very powerful queens. They had human sacrifice, which the Egyptians either didn't have, or had long since abandoned. A bit of a debate as to whether the Egyptians ever had it very early in their history. But the Nubians had, had human sacrifice and also for a long time they were under the thumb of Egypt.

Egypt would have what they call the King’s Son of Kush, a viceroy of Nubia, and he would be sent down to extract tribute in the form of all sorts of wealthy goods and nice things and wild animals and exotic goods. And bring them back to Egypt in order to stay, stay cool with Egypt. But at one point, was it now, was it the 25th dynasty or thereabouts? Late in ancient Egyptian history, when Egypt was starting to be assailed by outsiders, the Nubians grew so powerful that they took over Egypt or at least the south of Egypt. And there was what we call a Dynasty of the Black Pharaohs. And I'm just trying to think of the name of one of the … Taharqa. Yes, Taharqa was, I think. Was he the first of them or the last of them? I can't remember. But he, yes. Taharqa. If you if you look up that one T A R H A R Q U A, I think it is. Taharqa. One of the spellings. And he's one of the most famous Egyptian pharaohs who was a Nubian. And sort of brought the Nubian empire, well, I was going to say it was sort of on a par with Egypt, but it sort of took over Egypt for a time.

In fact, he was really trying to, as I understand it, where I read somewhere, he was trying to revive the fortunes of Egypt at that time and, and sort of take it back to the past and might make Egypt great again. Unfortunately, he didn't, he didn't stay the king.

Audience member 8:

Are there different dialects of hieroglyphics, like based on region or caste or anything else like that?

TJ:

Sorry. Can you, can you?

Audience member 8:

Are there different dialects or scripts for the hieroglyphics?

TJ:

Dialects - we don't know because we're not sure how it was actually pronounced. There are too a couple of different scripts. If you couldn't bring up the cursive. Yeah, Hieroglyphs are individual glyphs that are either carved or painted on the walls of the tombs or the temples. And they, the other one is cursive hieroglyphs, which is more of a equivalent to our handwriting. So, there's the two different ones there.

Hieroglyphs themselves evolved over time into Hieratic, which is the Greek name for priestly, and then evolved again into Demotic, which is the Greek name for popular. And Demotic evolved purely from Hieratic rather than from hieroglyphs.

And lastly, we get Coptic, which is a little bit more similar to hieroglyphs. And in actual fact, in the last 200 years, Egyptologists have been able to compare some words from Coptic and the words from Egypt. And from there we've been able to get a good understanding of the meanings and part of the sounds by convention that that come out with, with the sounds. It's a phonetic [clears throat], sorry, my voice is going. It's a phonetic alphabet, which we have. If we can show the phonetics.

JD:

This one?

TJ:

Ah no, next one. Yeah, the basic alphabet is a phonetic alphabet. But it's complex, complicated a lot more with two and three syllable words and also with word signs such as ‘ka’, which is a sign that's not in the alphabet. It's like that. And it means the soul. The ka, for the ka of whoever the deceased is and the ka is part of the, of the, the spirit or the soul. And another one would be ‘ank’. Very recognizable. You'd be able to recognize the ank. Which means life or living.

Audience member 9:

Thank you. I'm wondering if you can speak to the differences in materials and technique for art that was used for like, beautification or aesthetic purposes versus art that was used for cultural preservation and religious purposes?

JD:

So you're differentiating between art that was used for sacred context and non-sacred context? Part of what I would say, we could probably all say something on this, but I think a lot of art that was professionally done, and art tended to be professionally done because artists were professionally trained, tended to be done by and for sort of high-level people. And therefore, a lot of it was sacred art. You'd be looking at sort of everyday objects that weren't very aesthetic to find something that was sort of made, made by peasants, and then it wouldn't have an inscription because they were illiterate. That sort of thing. What would you say?

DK:

Nefertari

TJ:

Yeah, that's one of the most.

JD:

Okay, so that's that is sacred art from the Tomb of Nefertari for example. Needless to say, sacred art always has more images of gods, references to mythology, magic, or in this case, it shows a scene of Queen Nefertari, the chief wife of Ramses II of the 19th dynasty of the New Kingdom. This is a bit after Tutankhamen. And she's making an offering of a table full of food to the goddess Isis. I know that the goddess has cow horns on her head and we often think of that as Hathor, but sometimes Isis takes on the attributes of Hathor. And I think, Tina, we can see Isis’s name there.

TJ:

Yeah, that's right.

JD:

Yep.

TJ:

That’s correct. Up at the top.

JD:

A throne shape,

TJ:

It's on the second to the right.

JD:

Second from the right at the top.

TJ:

At the top. It's a throne shape, a flat throne You can see it up there.

JD:

Yes. I must say, when I came with photos for tonight, I didn't sort of photograph or didn't bring a picture of, say, you know, everyday objects like a stool or something like that, because we would tend to look at that and say, well, that's not so terribly aesthetic. If it was just sort of something that belonged to a peasant. Then of course, a lot of the peasants didn't have tombs built into which these things were placed, and therefore a lot of that has not survived.

And that is why the material culture of ancient Egypt is skewed towards the wealthy and then skewed toward the sacred. Yes.

TJ:

Can I just intersperse there. In the royal tombs in particular, such as this one, there was a lot of hieroglyphs. And hieroglyphs, the art of hieroglyphs changed over time. And you can get very finely detailed ones and you can get very fat fleshy ones as well. Depending on which time and what the fashion was at the particular time. Ah as Jasmine was mentioning, the tombs of the nobles. Now they're very different. And they don't contain as many hieroglyphs, but they contain a great deal more in illustrations. They could be very big illustrations, you know, cows and, and the field of the actual, there’s some illustrations coming up. I think it's the tomb of Paheri.

DK:

Yeah. This is the tomb of Paheri with his wife Henut and there is of these families holding a funerary banquet for him. And if you move on to the next slide, you'll see the rest of the family. And I think on the third, no first row of, first row of women are his sisters. And the hieroglyphs in this particular tomb are telling us that the third one is refusing the wine, but the servant is telling her this is for your ka. Drink until you're intoxicated. Make it a holiday. Listen to your companion. For her companion behind her, which is her cousin Nub-mehy is saying, give me 18 bowls of wine. My insides are as dry as straw. So, I think in the terms of the lesser people, if you like, the administrators, it's more about your everyday life, who you were, what you did, your family, being in the countryside. Whereas in the Royal Tombs, it's more your association with the gods and very symbolic. Yeah.

JD:

Yeah. I've got a scene, duh de duh, duh de duh de duh. Tomb of Seti I. I mean, this this tomb is epic. It's massive. Just huge going down there. So, this is Dynasty 19. I'll just speed through this rather than jumping through slides. You can see, you know, an image of I think Nut, that's Nut, the sky goddess, the hieroglyphs. Nut the sky goddess. Spreading her wings over the king.

Here you have one of the Books of the Dead. There are many different so-called Books of the Dead in English. The actual so-called Book of the Dead is actually the Book of Coming Forth by Day. This one is a different one. Is it the Book of Gates? No. I forget. This one anyway, is a text known as the Litany of Ra, where Ra, the Sun. Of course, the Sun travels under the Earth at night, they imagine and then is reborn in the morning. Ra the Sun. And when he goes under the Earth, being the creator god, the first creator. He sort of, how can I say it. Like a computer. He reboots himself, runs through all his programs and manifests as every single species he created.

And think about that. That's a really sophisticated idea. And here he is manifesting as all these different animals and even plants. And you go down further into the tomb, and you find scenes of Ra traveling under the Earth. There he is being pulled by the spirits under the Earth. And here he has a ram head, which is to do with the symbolism but he's being protected by a snake deity. They're traveling long under the Earth at night as he regenerates like the Energizer bunny. And he's being pulled along. This is a way of showing the passage of time, the hours of the night, going along the ropes, the snakes, the hours passing, and the on the bottom scene. You've got the Sun traveling along. It's like a comic strip, except without the dividing panels. And the Sun is traveling along, moving along, through time under the night, regenerating to be reborn in the morning.

And in the bottom chamber toward the burial chamber now. We've got Seti. Meets the gods in the afterlife. He becomes a god. He meets Horus. Horus, the God of Kingship, of which Seti is the earthly manifestation, the living Horus. And so, these are the sort of themes that you get dealt with in, that they deal with in royal tombs. And as Dean was saying, if you look at private tombs, which are still of wealthy people and still sacred themes, nevertheless, there's bits of, good point Dean, everyday life coming in. To the point of banter between people and, you know, talking about drunkenness and overeating at parties and things like that. Yes. And we know that sort of thing went on from some of the other inscriptions.

TJ:

Just to finish off there. The other aspect of art often came with statuary. Statuary as well. And again, what was in fashion, the royal statues in particular were very strong, and ego and strength was very much a power issue with the, the, sorry, the pharaohs and the pharaonic art.

However, when you come a little bit further down. Can you bring up the scribe? I'm just looking at the scribe. There are different statues that come through. One is the scribe and that's a lovely one because it shows a much more naturalistic aspect rather than the totally useful, continually on with the Pharaoh and the strength and power.

JD:

He’s got flubber!

TJ:

He's got Flubber.

JD:

He’s got middle-aged spread!

TJ:

He’s got definitely flubber. But you'll find that and I think you'll have seen one of those in the exhibition, that come through. And also, in the exhibition as well, there's a very good example of block statues and that was came through about the Middle Kingdom and that became a different fashion again. And it's of a man with his knees drawn up and he’s covered over with a cloak, and that cloak gives a blank surface, which allows a lot of hieroglyphs and a biography of that particular noble or whoever it was about. But there were particularly nobles and the richer end of society had those, whereas the poor end would have had the smaller shabti-type figures. Yeah.

Audience member 10:

More a topic and also kind of a question. But the topic is Egyptian mythology. And I'm more curious about what your favorite deity in Egypt mythology is?

JD:

Well, a lot a lot of Egyptian myths, scrolling down to the right place now. We saw this one coming too. Okay, lots of people say - whoops that's, that happened because I put my screensaver on by accident, whoops. Okay, just a quick scroll through of some of the most famous Egyptian gods. But remember, they had thousands of them. So, and people say why? It's because when an empire is made up of a lot of little villages that come together into a single empire and each village has its own god or goddess, and people later on try to say one god is an aspect of another god or one goddess is kind of like another, and you can smoosh them together. You know, this is how you end up with the confusion, which is Egyptian mythology. It is, in fact, multiple religions smashed up together.

But one of the, the four major tales of the creation of the world, this one comes from Heliopolis, which is the temple of Ra in Heliopolis, which is now a suburb of Cairo. This tells that Ra was the creator of the world and that his children were the atmosphere and the moisture, Shu and Tefnut. And their children were Geb, the Earth and Nut, the sky who arches over the world with a star-spangled body and her feet and her hands at the horizon.

And their children were Osiris, Isis, Nephthys and Seth. And then of course, in ancient Egyptian, that's not their ancient Egyptian names. Their ancient Egyptian names respectively are Asar, Usat, Nebet-Het and Set. And these Greek names, we know them by Osiris, Isis, Nephthys and Seth. And so, Horus is the son of Osiris and Isis. And, depending which Egyptian priest you talk to, some of them would say that Anubis, who's a lot of people's favorite god, comes from the union of Osiris with Nephthys.

I'm just going to skip ahead because I want to briefly talk about the murder of Osiris. And this is where some of, well, my favorite gods come from, a lot of other peoples as well. Osiris is quite a major god. Which which which were the cult centers of Osiris? The God of the dead?

TJ:

Abydos, and also in Karnak. And yeah, in Thebes.

JD:

In Karnak Temple. Okay, so I'll keep this brief because you can do the long, the short version of all these myths. But it sort of explains where some of the gods come from. So basically, it's the plot of The Lion King everybody. Two brothers, they’re jealous. The one kills the other who's the king. And then the son comes back for revenge. So here we go.

Osiris was the original King of Egypt, and he was murdered by his brother Seth, who tried to steal the throne from him. Osiris meantime, his spirit went into the underworld and they took his body, which Seth had cut up into many pieces and bound it together. Anubis was the god who bound them together. This is a lot of people's favorite god, Anubis, the god of embalming. Why a jackal head? Remember - it's a symbol. They didn't think there was a dude walking around with a jackal head. It's just a symbol. What it means is that there were jackals roaming cemeteries because they are carrion eaters. They eat dead meat. They don't kill animals. They just eat dead ones that somebody left there. So, if they find a human body buried in a too shallow a grave, maybe a poor person, they would dig it up and eat it. Okay, so that's a tasty treat for them. So, they look at cemeteries and say, dude, there's all these these jackals. This must be the god of this place. So that is why he's the jackal god of embalming.

So, he embalmed Osiris and made him into the first mummy, reuniting all pieces of his body. Because all the pieces of the body and all the pieces of your spirit have to be brought together. Death tears them apart, but you have to bring them together in the form of a mummy to keep the person’s soul and body intact and united. So, Osiris, having been united with all his other parts, went to the underworld to be King of the Dead. And there he is being mummified by Anubis with Isis and Nephthys mourning him at the head and the foot of the coffin.

Okay, so. And then there was the revenge of Horus. Horus is another favorite god many people have. Why does he have a falcon head? Falcons, if you watch them, they float in the sky, they hover, and then they go pew and they dive down and attack a mouse or something that they can see. And they're the raptor birds, so they attack. So, someone once said, I heard that they thought this was appropriate for a god that takes revenge.

So, Isis and Osiris magically conceived a son. His name was Horus, and here he is on the lap of Isis his mother. Notice the throne symbol on her head. It's like Osiris is the king and she's the throne. It's the symbol for her name. And that is Usat. So as in Egyptian art, often a word is a picture. And a picture is a word. Sometimes you can't do that in English. It's fantastic. By the way, the image of the Horus on his mother's lap was thought to be the origin of Christian iconography of Madonna and child. Because Egypt was the first great stronghold of Christianity where it transitioned from being just another cool cult that probably is a flash in the pan to something that's here to stay. That's another story.

Horus grew up and decided to take revenge for his father's death and to take the throne back, which he inherited, should have inherited. Now, during the battles between Horus and Seth, all sorts of terrible things happened. At one point, Seth tore Horus’s eyes out and then using magic, Nephthys, the wife and sister of Seth, who didn't like her husband very much behind his back, she used her magic to cure Horus. He had no eyes, so she put her magic into his eye sockets and his eyes grew back again. Whereupon he became whole and complete and the word for whole and complete is wedjat. And that's why we call it wedjat. The ancient Egyptian band aid. The magic Egyptian band aid. It cures and wards off sickness. It cures wounds and so on.

The living in the dead can both do with them. There was another battle, I’ll make this really quick. There's another battle between Horus and Seth, where they transformed themselves into hippopotami, which do actually fight in the river. They’re very vicious animals. Isis tried to help by harpooning one of the hippos. She got the wrong hippo, got her own son. He was not very pleased. He chopped his mother's head off. And so, she took a head under her arm, went back to Ra her great, great, great, great, great, great granddad. Said, look what he's done. But because she was the mistress of magic, she just put her own head back on. So, no problems.

And in one of the last battles, Horus and Seth decided to have a boat race. Horus was clever. He made a wooden boat and painted it to look like stone so it floated. Seth was not the sharpest tool in the shed. Smashed a mountain top, made a boat, put it in the river. It sank. Horus laughed at him.

Then finally the gods decided, we need to sort this one out. And a lot of Egyptian stories of the gods end up with everything going to court. Just like in real life, it all goes to court and Ra pronounces what's going to happen. So, he said, Right, Seth, you can be the god of storms and the desert and general chaos. He thought that was pretty cool. So, he went with that. And Horus then became the new King of Egypt, and that is why you see him often depicted embracing the pharaoh as we see here in the tomb of Seti I. And that is why you sometimes see a Horus bird perched behind or even hugging with his wings the crown of the king, because he Horus is the God of Kingship for the reason of this myth.

So, I hope that covers some of the popular gods that we think about. And it's good to know the stories of them, because I always say, if you know, Egyptian mythology, you know the story, suddenly the artwork makes sense, and all the objects start to make sense.

Event MC:

Wonderful. Well you please put your hands together and thank the panel very much.

More Episodes

John Mirosevich explores the varied history of Thonis-Heracleion, Egypt’s greatest Mediterranean port for 400 years.

Listen to Hon Dr Anne Aly MP who joined us at Afterlife Bar for a presentation on the Discoveries of Ancient Egypt exhibition.

Dean Kubank revisits the Temples of Nubia and the enchanting Temple of Isis at Philae.

Celestial Timekeeping in Ancient Egypt - Discover how Ancient Egyptians used the heliacal rising and setting of stars to construct their star clocks and civil calendar.

The life of the average Egyptian could sometimes be precarious and short. Broken bones, infections, and arthritis were all common among the general population.

Discover the story of the pharaoh Djedkare, his family and courtiers, and take advantage of the rare opportunity to hear from visiting international Egyptologist Dr. Mohamed Megahed of Charles University, Prague.

Discover the story of the pharaoh Djedkare, his family and courtiers, and take advantage of the rare opportunity to hear from visiting international Egyptologist Dr. Hana Vymazalová of Charles University, Prague.

Discover Egypt’s ancient legends of creation, death and resurrection. Tales of Ra, Osiris, Isis and Horus will unlock the meanings of the art, religion and funerary practices of ancient Egypt.

The Dynasty 6 Vizier named Weni the Elder, who lived about four and a half thousand years ago, had a detailed biography written on the outside of his tomb.

How, when and why was mummification invented? The answers may surprise you.

Ancient Egyptian Astronomy Unraveled - Discover how the Ancient Egyptians used their knowledge of the sky to design and position their temples, statues, and roads.

As part of our evening Afterlife Bar series at WA Museum Boola Bardip, we welcome a series of speakers to dive deeper into Egypt. Join us this week as we hear from Dean Kubank on Temples and Tombs.

Renowned expert in ancient Egyptian history Daniel Soliman delivered a fascinating talk, as we celebrated the launch of the WA Museum Boola Bardip's Discovering Ancient Egypt exhibition.