Ancient Egypt with Dr. Daniel Soliman

Renowned expert in ancient Egyptian history Daniel Soliman delivered a fascinating talk, as we celebrated the launch of the WA Museum Boola Bardip's Discovering Ancient Egypt exhibition.

With years of experience in Egyptology and as a curator of the Egyptian and Nubian collection of the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in the Netherlands, Daniel took us on a captivating journey of the exhibition's fascinating artifacts and discoveries. As a co-director of the excavation in Saqqara, his team's archaeological research is adding new insights into the ancient Egyptian culture, which he will share with you.

Audiences delved deeper into the history of ancient Egypt and had their burning questions answered by the expert himself.

-

Episode transcript

Ancient Egypt with Dr. Daniel Soliman

Craig Middleton: I’m Craig Middleton and I am a senior curator at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra. And I'll get back to that in just a minute. But before we get started, I'd like to acknowledge that we are gathering, meeting, sharing, thinking, acting on the lands of the Whadjuk Noongar people, the traditional custodians of this place and I'd like to pay my respects to Elders past, present and emerging. And this engagement that we have and that we feel and that we benefit from First Nations communities is a similar reason why we're here today. To engage with both ancient and modern societies and cultures. And what I'm, of course, talking about is that of ancient Egypt and modern Egypt, which would not exist without ancient Egypt.

So, I mentioned I'm from the National Museum of Australia, which might seem kind of funny, why I've come from Canberra to introduce our guest speaker today. But this exhibition— Which I hope you've seen, who's seen this exhibition? Yeah. And if you didn't put your hand up, I hope you got a ticket. This exhibition, Discovering Ancient Egypt, is not only a partnership between the WA Museum Boola Bardip and the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in Lieden, the Netherlands, but it's also an Australian partnership between WA Museum, the National Museum of Australia and the Queensland Museum network. And it's only in partnership across our country that we can bring the world's cultures to Australian shores so we can all engage in these, these deep and important histories.

And it's my pleasure to introduce our guest speaker today, Daniel Soliman, who I've had the pleasure of connecting with over the past few days, because before now it was only over email that we've interacted with the Rijksmuseum in Leiden. But Daniel has quite a big CV, and I'm going to read only parts of it to you, but I'm sure it doesn't even scratch the surface.

But Daniel studied Egyptology at Leiden University, and in 2016 he obtained his PhD, which took its focus on identity marks and literacy in the community of necropolis workers at Deir el-Medina. He then worked as a lecturer and researcher at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark on a research project about the economics and administration of monumental tomb building during the New Kingdom, which, of course is one of the major periods in ancient Egyptian history. And in 2018 and ‘19, Daniel contributed to a research project at the British Museum on the illicit trade in antiquities, which sounds really, really fascinating, but not the topic of today's talk. And since 2019 has been a curator of the Egyptian collection at the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, the Netherlands. And there he conducts research, cares for the ancient Egyptian collections in Leiden, and also creates amazing exhibitions like the exhibition some of you have seen, and I assume the rest of you will see very soon.

So I'm going to stop talking and welcome our guest speaker Daniel to the stage. Please give him a round of applause.

<applause>

Daniel Soliman: Good afternoon. I'm Daniel. It's a delight to be here to speak to you. It's been wonderful in Perth. I've been having a great time meeting all of the colleagues working together, and it's an honour to speak to you tonight. So, I will talk about this exhibition and I'll talk about some of the key points that you can see in the show. I hope you all have a visit. And I'm sure that some of you will know quite a bit about ancient Egypt, so I will, I will try to mix it up. I will both talk about some general points that you can see the exhibition, but I also try to add here and there to some, some new perspectives that come from ongoing research.

So let's start with, where this collection comes from, right? This is an exhibition called Discovering Ancient Egypt that includes bits and pieces— Well, not bits and pieces. They're actually highlights from the collection of the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, which is in the Netherlands, in North Europe. And of course, we are talking about artefacts from Egypt itself. So here is a look at the globe and you can see that there's quite a distance between these places. These are some shots from Leiden. It's a very small, mostly university town at the moment, with a charming historic centre. You can see some of the canals. And the museum is this rather unassuming building on one of the canals. You can see it on the right. Nevertheless, this is a museum with one of the, let's say, top five most important Egyptian and Nubian collections in Europe, and it is frequented by visitors from all over the world. It has many other collections, also collections for the Near East and Greece and Rome. But it's most famous, I suppose, for its Egyptian and Nubian collection.

And in fact, one of the first antiquities you see as you enter the museum is a temple from Egypt. It was donated by the Egyptian state to the people of the Netherlands. And we'll come back to the temple later. The museum was founded in 1818 by the king of the Netherlands, King William I, and the first director of the museum was Caspar Reuvens, who actually also became the first professor of archaeology in the world.

So let me tell you a little bit about this time frame. Right? This is the beginning of the 19th century. And King William I of the Netherlands has just proclaimed himself king of the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg in 1815. So, just three years prior to the foundation of this museum. And so with this young kingdom, there come efforts to shape a national Dutch identity and to establish the kingdom also on the international stage, European stage, and that included also some cultural politics. And at the time a Western empire, small as it was, needed also national museums with collections that could cover antiquity and art[?]. So, what one hoped could rival those of the British museums, the French museums and the German museums. It is also good to realise that at this time the study of the ancient worlds came from this desire to, to acquire knowledge, to understand the world. But it is also vital in the process of intellectually claiming the cradle of Western civilization in these ancient cultures; and by collecting artefacts, this was also a physical claim, in a sense. And that includes ancient Egypt. Now, the Leiden Museum, again, founded in 1818, had a few Egyptian objects already in Leiden but in wanting to become a great museum, needed to collect more, and so in the 19th century they benefited a lot from the political situation in Egypt at the time when there wasn't really a legal framework for trading antiquities.

And so there was this large and ongoing intensive trade in antiquities, in Egyptian antiquities. So most of the, ah, the core of the collection, the Egyptian collection of the museum was acquired through these networks and channels of European and Ottoman imperialism and colonialism. But it is a very complex situation, with also Egyptians, local Egyptians, working, being part of those networks, sometimes also benefiting from them.

Anyway, these are important histories that we try to, to study when we talk about the collection that we have to acknowledge as well. We have to also acknowledge this power imbalance that was present at the time, and through which many of these objects were able to travel to the Netherlands. Well, apart from talking about the history of the collection, we can obviously also talk about the history of ancient Egypt. And the collection of the museum is rich enough to tell quite a bit of the history of ancient Egypt.

And this is what you will see in the exhibition as well. The first part, in fact, is basically a timeline through the various periods of ancient Egypt, from pre-history all the way to Roman imperial periods. And historians and Egyptologists have divided the ancient Egyptian history in different areas. We've already heard the New Kingdom. So there are a number of other periods and it makes sense to divide up our timeline in these in these different periods.

But first of all, we have to acknowledge that there's much more that comes after the Roman Empire. And these are periods that are worth studying in themselves. And secondly, I would say that it's, it's— This timeline sometimes takes away your, really, the feeling of the fact that this is such a long history, right? We're talking about thousands and thousands of years, really. Centuries. Some of the objects that you will see in the exhibition are over 8000 years old. The bulk of the, of the objects in the exhibition dates between five thousand and two thousand years ago.

There are in the exhibition a number of thematic sections. They cover different aspects of life in ancient Egypt. One of them is the section that we’ve called ‘daily life.’ And here you see a number of objects, including this oval basket that was used to store, probably, toiletries and things like jewellery. You see luxury items made from stone. For example this, this fantastic vase that is decorated with handles with ibex heads, that was used as a container probably for perfume or ointments. And that wooden object that you see is a so-called head rest. It was used to sleep on. So, either directly on this or with a pillow. It seems to be uncomfortable, but people have tried it. And it's, and in fact, it's still in use in some in some cultures in Africa. And it seems to be comfortable. I've never done it myself. The section includes other items used by people to adorn, adorn themselves. Jewellery, fantastic necklaces made from gold, made from precious stones, and oftentimes including amulets, as you can see.

There is this bronze mirror that was used to well, of course, as a mirror, right? So, what you did is you polish the disk and then you could actually see your reflection in the time when they didn't have mirrors in the sense that we have them. In this section, you can see a number of amulets that were used by people in daily life. They would have been worn on necklaces or on bracelets. And in a sense, they're like good luck charms that could protect people against evil. And oftentimes they are depictions of gods, particular gods. For example, here you see an example of the goddess Taweret, the hippopotamus goddess used to protect the family in general and pregnant women in specific.

And you can also see a depiction of one of my favourite gods at the top. His name is Bes. He is this little dwarf. He's got the manes of a lion. He's got this plumed headdress. And he also was a protector of family life and he could ward off evil. This is why we often see him depicted [as] in front of you. He's got his mouth open. He sticks out his tongue. He shows his teeth so he can scare away evil spirits.

The exhibition, I think, I hope, will also help the visitor reflect on our own lives. Right. That's just one of the things why studying the past is so interesting. So in our societies, most of our societies, contemporary societies, writing is ubiquitous. We cannot do without writing most of the time. And ancient Egypt is a very special culture, ancient culture, and because it was a culture that also had writing; it is in fact one of the first cultures to develop writing, probably independently from the Mesopotamian forms of writing. And as normal as it is for us to use scripts and as, as big as the connotation of script may be in relation to ancient Egypt, right? We often think of hieroglyphs. We still have to realise that it was probably just the 1% of society that was actually formally trained to read and write. And not just hieroglyphs. In fact, there was different scripts that we use in ancient Egypt, more cursive scripts, right? Hieroglyphs were more of a monumental script used for monumental, for monuments like buildings, like stela, like temples.

But there were cursive scripts used to write everyday documents, used to write letters. And here we have an example of a letter. Later, the ancient Egyptians stopped using these, these old forms of scripts and adopted the Greek scripts with the addition of a number of signs for sounds that do not occur in the Greek script. And this is what we call coptic. And it was in use after the Roman Empire at a time when many Egyptians started to convert to Christianity. And in fact, it's still, in a sense, in use today with the Christian minority, Christian communities, in Egypt, to this day. And in fact, it has been key in, as we say, deciphering the ancient Egyptian script.

In the exhibition, you also get an impression of religious life in ancient Egypt, and it has its own section in a way, and that would almost give you the impression that this was also a separate sphere in life, in ancient Egyptian life. But most likely, religion and ideas about the spiritual world would permeate through everyday life all the time. This is really part of people's life, people's lives. And we see in this section examples of statuettes that were created for gods. They were made, for example, from bronze or from wood, as we see here. This is one fantastic example, very well preserved, of a statuette made from wood. And these statues would be placed in temples. They were votive gifts. They were donations, as it were, to the gods and the donator hoped to receive the favour of the gods by giving this present. And oftentimes there's an inscription on it, honouring that particular deity, but sometimes also adding the name of those donator on it.

You also see some tools that were used in temples. There is this fantastic. We call it a sistrum. It is a sort of a rattle musical instrument that was used to accompany rites in temples. Well, I mentioned that you could donate statues to the gods, but there were also other forms of offerings that you could bring in temples, and one of them is quite special. You can see a few examples in the exhibition. These are mummified animals and well, there's different mummified animal remains that we found from ancient Egypt. Some of them, a small minority of them were pets that were buried together with their owners in tombs. But the majority of these of these animal mummies, we know very well, were in fact also these votive gifts. So the ancient Egyptians oftentimes associated a particular god with a particular animal, right. I'm sure you're familiar with this concept. So what they would do, they would breed in the area of temples, animals of that particular god. So this could be crocodiles, snakes, ibises, fish even, cats, and once they passed away – and we think sometimes they may have been killed for this purpose as well – they would be mummified and people would go to the temples to purchase one of those mummified animals and would then donate it in the temple to that god. Or, not so much in the temple, but in underground galleries and catacombs related to that temple.

And the reason for this is that they, they believed that once the animal had passed away and was mummified, it would go into the afterlife, would go into the world of the gods, and then it would act as an intermediary between the donator of the votive mummy and the gods. And so it could convey a message to the gods and could ask for the favour of that god. We study these animal mummies, for example, by using X-ray imaging, and we can see inside these mummies without having to open them. And this is sometimes very revealing. Sometimes we can see that even though on the outside, this mummified animal looks very clearly like, for example, a cat's. But then we look inside and we see that there's not so much of that cat actually inside. It's maybe a few of the bones of a cat. Sometimes there's nothing. There's no animal remains at all inside. We don't know exactly what the reason for this was. Maybe this was an economical thing. Maybe this was a trick by the people selling these remains. In the case of just, you know, a few of the bones of particular animal, we think that this has to do with the idea that a part can represent the whole.

Ancient Egyptian religion is famous for its many, many gods, and you will be introduced to a number of them in the exhibition. One of the most famous gods, most important gods was the god Osiris, who was one of the most important gods of the afterlife. He is oftentimes depicted, as you can see here, as a mummified god. He was, in fact, according to ancient Egyptian mythology, the first god to be mummified himself So he's represented as such. He's holding two sceptres because he is the king of the hereafter. He wears a long elongated crown, and he is sometimes depicted with a black or a green face, and this is a symbolic colour. It symbolises either the black soil from which green plants can come to life. So it symbolises new life, or rather, continued life after death. And the ancient Egyptians really, once they passed away, tried to identify themselves with Osiris. They hoped to become like Osiris so that they could continue to live in the afterlife. In order to get there, in the afterlife, in the kingdom of Osiris, the Egyptians believed that they had to pass a series of judgments. One of them is oftentimes depicted in texts that we call Books of the Dead.

This is an example of one of those. It's a papyrus inscribed with spells, magical spells, from this Book of the Dead. And it belonged to a man called Nesmut. And here we see one of those most important judgment scenes. And some of you will probably be familiar with this. It's the weighing of the heart. So the ancient Egyptians believed that the heart was the seed of, really, the intelligence and also memory. And so this heart had to be weighed on the scales against the feather, an ostrich feather, of the goddess Ma’at. And she was the goddess of order and justice. So the heart had to weigh, had to balance out, had to be just as light as this feather. And if this was the case, then the gods— Right, you see them represented here at the top. There's twenty— I'm sorry, forty-two of these gods. They preside over this, this hall of justice. They would then allow the deceased to enter the realm, the kingdom of the god Osiris. If this wasn't the case— And mind you, all of these spells are there to help actually succeed the deceased to get into the afterlife. So the outcome had to be successful. But if this wasn't the case, the heart would be devoured by abeing that is also depicted here. It's a bit small, but I hope you can see it. It's a, it's the figure seated on a blue structure and it represents the goddess or rather the being, Ammit. And she is the devourer. She is depicted with the head of a crocodile, the front part of a lion and the back part of a hippopotamus. So, three very ferocious, powerful animals.

It's— I have to stress that it's a misconception that the ancient Egyptians were obsessed with death. Right? This is also a bias that we as modern scholars sometimes put into the material. For example, by using a term like the Book of the Dead. This is not an ancient Egyptian word. I’ll come back to this. It is also an oversimplification to say that the ancient Egyptians believed that they had to be reborn in the hereafter, that they had to live for eternity. We see from these spells, from, again, this so-called Book of the Dead, that there is many other things that are very important. This is a bit more of a complex situation. The ancient Egyptians really— What they really believe is that the deceased would be transformed from a mortal into something else. A more powerful being, a being that would exist in the world with the gods and had magical, magical powers. Could travel between different places. Places as depicted here, for example. This is not the realm of Osiris, but another place in the hereafter that the ancient Egyptians called the Fields of Reeds. And we see, we see the pictures here on this, on the same papyrus scroll, this man Nesmut. The Field of Reeds is a place where the deceased could work the land in order to provide for himself, in order to provide drink and food and clothing. And it is also the place where the deceased would meet different deities, as well as their own deceased parents. They would be reunited in this Field of Reeds.

Let's go back to the Book of the Dead. Again, this is a modern designation for this type of spells. The ancient Egyptians called these, this group of magical text— They call it ‘the spells for going forth by day’. This means that they believed that, again, the deceased would be transformed and a manifestation of the deceased could travel between the hereafter and the world of the living. And it did so in the shape of a being that we call the ba. You can see examples of what the ancient Egyptians thought the ba looked like. It's basically a bird. Again, it's this power that the deceased gets, the power to fly, to travel to different places, but it has a human head and one of them is depicted here with the green face of Osiris. And so, in the shape of this bird, the deceased could fly out of the tomb and into the world of the living during the day, right? This is why these spells are called ‘coming forth by day,’ because this happens when the sun rises. Now, when the sun sets, the ba has to fly back into the tomb to be reunited with the body in order to come back to the hereafter.

And that's one of the reasons why the ancient Egyptians wanted their bodies to be preserved and mummified their deceased, because the body was very important for this aspect. Here we see, ah, funerary statuettes. It is mummy shaped. You can see it represents the deceased, a man who is called Tal. And if you look closely, you will see on his chest there is a bird. And in fact, this is again, this ba bird, right? So you can see the different forms, two different forms. And there were many others that the ancient Egyptians believed made up a single person. So we have the body of the deceased. And on top of it, this manifestation, this ba bird, and here they are reunited. We have many of these type of statuettes, these funerary statuettes. And you can see a number of them in the exhibition, and we call them shabtis.

And this is an ancient Egyptian word. Shabti means ‘one who responds to the call’ and answers it, so to say. And the meaning of this, the meaning and the function of these type of statuettes developed over time. We think that initially they were mostly there to be replacements for the body. Should something happen to the body of the deceased, you would still have these statuettes. Again, yes, you can see they represent the deceased in mummified form, but then they also get another connotation over time. I hope you can see on the slide that these figures oftentimes wear agricultural tools, these hoes that they can use to work the land. And this goes back to that Field of Reeds that we saw earlier. These statuettes were made in series. And we believe that – mostly because of the spell that's written on them, sometimes – they were meant to answer to the call of the deceased to do the work in these fields for them. So they could actually work. They were like substitute workers in a, in a way. And sometimes these people were buried with entire sets of such statuettes, one for every day of the year. And sometimes these were then also grouped again in groups of ten, and each would have a supervisor looking after them. So really making sure that that work got done.

The Egyptians, the ancient Egyptians, believed that they— We’ve already seen this, in fact. Right? The body needed to be protected. And protection came in many forms, and one of them was amulets. Many of, many types of amulets were placed on the body of the, of the deceased, sometimes in the wrappings of the, of the mummy. And we see a few examples here. One of them on the left is a snake head. This is a very powerful— I mean, from a very powerful type of stone, a very red and dangerous stone. It would prevent the deceased from being attacked by snakes in the, in the afterlife and it was often placed on vulnerable parts of the body. So on the neck, for example, on the throat. We see the udjat eye, the eye of Horus, which, it brings protection in general. It makes sure that the body is complete, remains complete. And you see another amulet in the shape of two fingers, and it was probably placed on the part of the body, the lower abdomen, where an incision was made during the mummification process when the organs were removed from the body. There's various other types of amulets— We'll skip over this for the sake of time.

I want to go to these four amulets. They represent the four sons of Horus. And, well, I've already mentioned that the ancient Egyptians mummified their dead and as part of the process they would remove the organs, and four organs were very important. They were removed from the body in order to preserve it. The deceased would need them still, to function in the afterlife. So the lungs, the liver, the stomach and the intestines, they were removed and separately they would be placed in vases. And each of these vases was in turn protected by one of the sons of Horus. So these sons of Horus, they are also placed in the shape of amulets on the body, to provide extra protection.

Besides protection, the deceased needed sustenance. And one way to get that was by working the fields in the Fields of Reeds. Another way was by receiving offerings from the family members of the deceased. They would go to the tomb. This was usually a monumental structure. And, mind you, I'm talking about very much the richest people in ancient Egypt who could afford such things. They would have a very large, monumental tomb. And the family members of the deceased would come to the tomb to bring offerings. And if they couldn't do so themselves or, let's say over time, when they didn't feel this was still important, they could hire priests to do so. They would actually bring offerings.

But another way to ensure that the deceased had these offerings was to place these type of stones in the tomb. We call them offerings stones. And well, on these stones offerings could be placed. And we see that this is actually designed to do so. There is a channel for it, for draining fluids on it, which means that people could pour liquids like water, like beer, on it. But it also depicts a number of breads, vases, meat that the ancient Egyptians believed through magic would become real and so the deceased could receive them in that sense.

Similar to that concept is this fantastic wooden model that you can see in the exhibition. It is a model of a brewery. So we see a number of figures there working to— Sorry, I said brewery, [but] it's a brewery as well as a bakery. It's, it's people working with grain. And beer and bread, they're closely related in ancient Egypt and they were, they were really the staples of everyday diet. And you shouldn't think of beer, ancient Egyptian being in the sense that we drink it nowadays. It was more of a porridge, probably. It was quite a bit thicker and it didn't, did not hold so much alcohol as our beer, probably only 1% or 2%. And it was a very important way to consume grain, but also to get clean water in you, right? Because you would have to process the beer and it was a source for water. So having a model like this in your tomb with your funerary equipment would ensure that the deceased would have enough food.

We have lots of sculptures from ancient Egypt. Some of them come from temples, others come from tombs. This is an example of a statue that we think comes from a tomb. It represents a lady called Walwi[?] who holds her arm around the shoulder of her husband, who was called Nutamun[?]. It was probably made around 1200 B.C. and it probably stood again at a temple and it represented the tomb owners. And so through the statue, the tomb owners could still communicate with the living. The ancient Egyptians really believed— Not only communicate, it was also a way for them to receive these offerings that would have been brought to the tomb.

Now, the Egyptians, of course, buried their dead— You know, again, the rich people would have been buried in coffins in which the mummified body would be placed, and these would be decorated with magical spells, symbols that would protect the deceased. It's a type of protection in two ways. It's both a physical protection, right. The body goes into the coffin and it's protected in that sense, but it's also a magical protection through the spells, the magical spells that are inscribed on it.

But more than that, again, I want to emphasise it's also part of the transformation, as is the mummification process as well. And you can see that in the coffins, by the elements that these deceased who are depicted on these coffins are depicted. The elements that they have. So the wigs that they win, it's maybe difficult for you to tell, but they are actually the same wigs that gods would wear. So you can see that they are given divine features, which gives them the power to continue to live in the afterlife.

We study how these coffins were made. I'll just go back really quickly. We study how these coffins were mades and we try to identify the types of wood. Now, ancient Egypt was very dry in general, dry and arid place safe from, of course, the banks of the Nile and parts of the north where there's much more green. And it is actually because of this very dry climate that so much of ancient Egypt is preserved. Because it would be contained in tombs. Very dry tombs. Not a lot of oxygen. So, things like wood are actually very well preserved. It's incredible because of this dry climate overall, which would have been scarce. There were types of woods that were local and that were also used to produce to create coffins, like the sycamore fig. But other types of high-quality wood would have been sourced from, from outside of Egypt, from the Near East, from Nubia.

And because wood was so scarce, we can see that some coffins are actually patched together from different types of wood, sometimes coffins, even, coffin fragments that were reused. So studying these coffins to understand their production also gives us an insight in the social, economic aspects of life in ancient Egypt.

In later periods, in addition to wood, they would use something else, a material that we call cartonagge and it is a method that is similar to papier maché. It's different layers of fine linen together with sometimes bit of papyrus and then a layer of glue and stucco, which then can be painted. And you can see examples of two coffins made from cartonagge here, as well as in the exhibition, of course. In the Greco-Roman period, we see also that it becomes fashionable to create separate elements also made from cartonagge that would be placed on the body of the, of the deceased, separate pieces of cartonagge. For example, a mask that would be placed on the face of the deceased. This one has as a golden gilded layer. It's a golden face. And again, that's a part of this transformation that happens at the moment that the deceased is buried. This golden face is again meant to represent the divine aspects because the ancient Egyptians believed that the flesh of the gods was made from gold. You can see in the exhibition a number of videos that show experts talking about the research that they conducted in the collection, and it also includes the research on the coffins.

We've been using different methods to study the coffins. As I mentioned, one of them is by using non-invasive imaging, a technique called visible-induced luminescence, which allows us to see what type of materials were used in the painting of these coffins. For example, the image on the right, the black and white image. It shows a number of areas lighting up, as it were. They're very bright and it shows us where the painter’s used is a particular material called Egyptian Blue, which is very, very common in ancient Egypt and special, very special to ancient Egypt. We also do CT scanning that allows us to see through the construction of some of the coffins and really gives us an impression of the bits and pieces that they used and how they are connected to each other.

Now, here's a quick warning. In the next slides I will show you images of human remains. They're all wrapped in their original bandages. But if you feel you’re uncomfortable with these images, I ask you to look away for a little bit. I will discuss them in the way that we discuss them in the exhibition because we, we talk about the way that the ancient Egyptians mummified their dead and what we can learn about the deceased.

So here is an example of one of the bodies, the mummified bodies in the exhibition. It's, again, completely wrapped in its original wrapping. You see a layer of beads on top of the actual wrappings. Again, it's a part of protection and a part of the transformation that the deceased which undergo. I think, through the centuries, really, through the centuries, people have been interested in these ancient Egyptian mummified human remains for various reasons. Some of them we find very difficult to understand nowadays.

For example, the fact that through the ages people believe that the black resin that covered the bodies, that helps preserve them, in a sense, had medicinal properties, and because of that, they would actually ground up mummified remains in order to consume them as medicine, a practice that existed for a very long time, even well into the 20th century. Very difficult to imagine this nowadays. But this happened and it's a very tragic part of the ancient Egyptian history. Nowadays, we are still interested in the bodies. We try to understand more about the lives of people led by studying the skeletons. We get a sense of, well, the physical, the physicality of their lives. But we also study the mummification process.

We study, we show this in the exhibition by looking at some of the instruments used during mummification. Famously, of course, the ancient Egyptians used to remove the brains from the head by using a hook, as you can see, through the nose in order to remove the brains which— They weren't particularly, which weren't particularly significant to the ancient Egypt since, again, it was the heart that was important. It had to be weighed in the afterlife. The other four organs, the lungs, the stomach, the liver and the intestines, they were preserved. The brains were usually removed. The heart was most of the time kept inside of the body so that it could be used in the afterlife. But we know through studying the mummified bodies that sometimes the heart, too, was removed. So it really depends on the period that we're talking about. And so not every mummified— Not every mummy is the same, basically. Very quickly we think again the mummy, mummification process was not just used to preserve the bodies, right? That was important as we’ve noted, for the body to be this, this gateway between the afterlife and the world of the living. But it was also a part of the transformation process. So wrapping a body with linen holds special significance because statues of gods in temples also would be wrapped in linen cloth, cloths. This linen is in itself significant. The resin used is not just for the preservation. It's also used to give the body these divine aspects.

So, all of this we, we understand better by studying the bodies. Okay. I think I've rambled for quite a bit. I'm looking at my colleague here. Should we perhaps wrap it up so that we have some time for questions? Yeah. Okay. All right. So I'll skip through a number of slides and I'll show you one thing that I, that I really want to share with you.

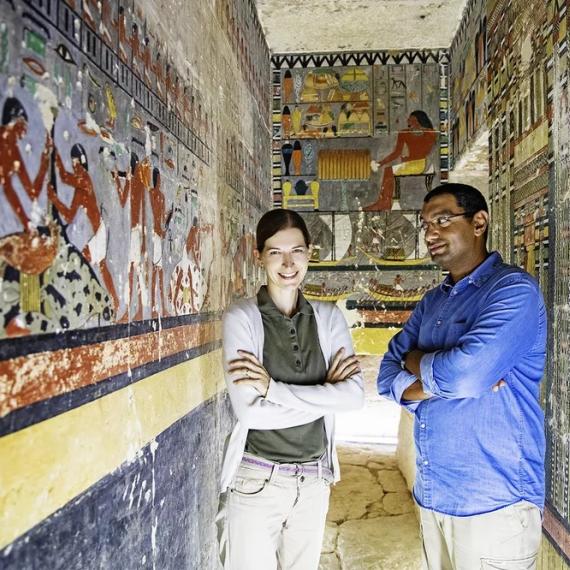

We talk in the exhibition about a number of excavations that the museum was involved with. One of them is at the site of Saqqara and one of the things that I find most interesting about the exhibition—well, personally it's one of my personal favourites—is a video that you can see at the very end of the exhibition, and it is the result of a research project that we carried out at the site, that deals with the contribution of our Egyptian colleagues. Because most of the time when we talk about these archaeological works, these projects, especially in the past, right, not so much nowadays, but in the past, we've mostly been celebrating the Western contribution to this science. But of course this work cannot be done without the help, without the collaboration with many of our Egyptian colleagues on site. And so this video is dedicated to exactly that. The various workmen that do much of the digging onsite. The various inspectors, Egyptian inspectors. Specialists, restorations specialists, pottery specialists who continue to work with us as a team. A number of them are highlighted. Some of the people of Saqqara have been with the excavation for decades, not just with the mission, not just with the research project that the Leiden museum is involved with, but also many others. And I highly recommend that you have a look and see their stories and how they feel about the work that they, that they do.

And I will leave it at that for now. And I thank you very much for your attention.

<applause>

Daniel Soliman: So I think there's, there's time for a number of questions. There's a microphone that will be going around, I assume. So, if you have any questions, by all means.

Audience member 1: So, would— You know how much of the time wealthy people got high quality mummification?

Daniel Soliman: Yes.

Audience member 1: But what about normal people? Would they still get quality mummification or would they just be left to decay and in the afterlife, would they still be considered to becoming gods in the transformation, or would just the normal people, just, still be normal people in the afterlife?

Daniel Soliman: This is an excellent question. Can I applaud that for a second?

<applause>

This is an excellent question. And it is one of the problems with talking about ancient Egypt through the objects of a museum collection because, yes, this is a very important question, but at the same time, we don't have enough evidence for this, especially not in museum collections. So let's come back to, to what you said. We know, of course, that also normal people—and I say ‘normal people’, less rich people—they were also buried. Sometimes they were mummified, but in a way that was a bit more, a bit cheaper or a bit less expensive. Some people were not mummified, but were just placed in the ground together with a few objects that they could take with them into the afterlife. And so we honestly don't know too much about what these people thought about the afterlife because they were not buried with large tombs with texts that can inform us about this. We do know that if we're lucky and we find a burial of these people, if we're lucky, we find amulets. And these amulets give us an idea of what they thought of the afterlife. But this is very much a research question that many archeologists are dealing with. They are trying to ask exactly the questions that you're asking. So, I'm very happy that you brought this up. Thank you.

Audience member 2: I just had a very simple question. Right at the beginning, and on one of your early slides, there was a basket under daily living.

Daniel Soliman: Yes.

Audience member 2: Was that a replica or, in that fantastic condition that it was, is that an original?

Daniel Soliman: Is an original, yes.

Audience member 2: That’s amazing.

Daniel Soliman: Yes, it is amazing. And again, we go back to the fantastic climate, fantastic for us as archaeologists, in which much of this material is well preserved. The exhibition contains, I think, let’s say, ah, 98% originals. There's a few replicas here and there, and they will be indicated as such when you go through the texts. But yeah, isn't it amazing how well preserved this is? Yeah.

Audience member 3: Can you tell us a little bit about the process of getting the pieces here from the Netherlands and whether you use different transport carriers to mitigate risk?

Daniel Soliman: Yes, also a good question. This has been in the planning, of course, for a long time. The exhibition here is part of a larger tour. So, the objects that you see here were previously in Korea and before that, in Japan. I must say this is a completely unique exhibition. So the stories that are told here are very different from the stories that were told in Korea and Japan, but the pieces are the same.

So before they were here, they were in fact in Korea. Before that, they were in Japan, as I mentioned. Now, the story of that process is very complicated because it happened just as COVID hits. And we had to come up with all sorts of solutions because travel was very much restricted. In fact, we had to do the installation of the exhibition mostly digitally with a team of experts present, Japanese experts present. And fortunately we had worked with them before, so they knew the collection very well. And we had to give them directions using— There was a camera crew, basically there to follow their movements. Now, from Korea to here was a much easier process because the collection managers of the Lieden Museum could travel together with the pieces. And we also work with professional companies that specialise. They’re professional art handlers that know how to do this.

But then, of course, getting all the permissions to move the collection from one place to another is a whole process in itself and requires careful planning. And then once they're here, installing them is also very much a collaborative effort. And we've done it together with the colleagues at this museum, at the WA Museum, and it has been a fantastic collaboration, which again requires lots of planning. I hope this gives you a bit of an answer.

Audience member 4: Hi Daniel. I really enjoyed the exhibition. Something in particular I thought was interesting was the way that it acknowledges the importance of Egyptomania and popular culture influencing what we think about ancient Egypt and also, you know, reflects a lot as research in an ethical presentation of human remains. But what I found interesting in one detail in the jewellery case—and you showed some of those pieces in the talk—was that it mentions that the form of the necklaces might not have been the ancient form or ancient combination or pattern of the beads, but has been passed down from stringing together random beads on the antiquities market in the 19th century. I've never seen that actually referenced in an exhibition before, so I'd like to say that's brilliant. Do you have any other objects, perhaps not in the exhibition or not even on display at the RMO, anything in storage perhaps, that is, um, comes down to us from the 19th century antiquities trade and has been affected by it in its form? Like beads rearranged into other objects or a mummy cloth that's been repainted on the tourist market. Do you have anything like that in the RMO collection?

Daneil Soliman: Yes, going through it— Thank you for your question. Going through the objects in my head. Well, of course things like bead nets, necklaces, as you say, they come to mind. We must have examples but nothing else pops up now. Well, we have of course, the oars. It's not really an answer to your question. We have the oars forgery right from the 19th century. So they were bought on the antiquities market and weren't properly understood at the time but were purchased anyways. We have rearrangements, in the sense that we have mummified bodies that were purchased at the time—and this is such a sentence to say, but this is what happened— The bodies were purchased in coffins, which then later were found not to belong together. Again, a result of the art market where an art dealer would just say, okay, I've got a body, I've got a coffin, let's put one in the other and sell them together to get more money. Surely there are other examples. If you, if you want, I can have a longer think about this and get back to you.

Audience member 5: Hi. Thank you very much, Daniel. You briefly touched on this earlier in your presentation, but I wonder if there are any plans to return any of the pieces to Egypt or have they been gifted? What kind of a relationship is there around those?

Daniel Soliman: Yes, well, this is a debate that is much more relevant nowadays than it is, let's say 50 years ago, 20 years ago. And so, yeah, we think about these questions. And there is this debate going on about whether the objects that were acquired through the art markets in the 19th century, whether they should go or they should be returned to Egypt. There's different thoughts about that. And one thing I want to emphasise is that this can never be a unilateral decision, right? So you need to make such a decision together with the source country. So it would mean that, first of all, I suppose there should be an official—not even an official, a request in general—from the Egyptian side and then we sit down together to see whether, what we can do, right?

Because—besides the point, but it is true—there are also practical obstacles for something like this. This is a national collection, which means that the museum cannot decide whether something goes back. This is a decision that would have to be taken on a national level by the Minister of Culture. That doesn't mean it can't happen. In fact, the museum can advise the minister to do, to make, to make that choice. So technically it could be done. But again, it would have to be done together with the Egyptian parties who also want it back, in fact. And what we see at the moment is that the Egyptian government is mostly interested in returning artefacts for which they know that they were illegally acquired through art market or objects that are so iconic that they come to, that have come to represent ancient Egypt and are abroad. You know, something like the sculpture of Nefertiti, for example. And the museum in Leiden does not seem to have pieces that are that iconic that they would have to be requested for repatriation. At least, it hasn't happened so far.

Audience member 6: Hello. Yes, another question about the afterlife. You mentioned that the Book of the Dead is probably translated as the ‘book of coming forth by day.’ So normally when you think of the Egyptian afterlife, it's a bit like the Elysian Fields. You go off to the Field of Reeds and you've got a great life and shabtis serving you. But is it part of their idea that the dead could visit the living or be active in our world still? Is that how they imagined it?

Daniel Soliman: Yeah, pretty much. We know that the deceased in the world, well, they could travel to the world of the living and in a way they could interact with the living. In fact, we have examples of people writing letters to the deceased. There is a famous one in the collection of Lieden, and it's unfortunately not part of this exhibition, but I can tell you about it. It's a, it's a very interesting story. It's a man who writes to his deceased wife, and we get the impression, he's not very explicit about it, but we get the impression that he feels that she is, or rather a manifestation of her, is haunting him during his life. And he goes on to list how well he took care of her during life and when she became ill, and the doctor that he got for her, and that once she had passed away, he mourned her for two years and did not look at any other women. And you almost get the impression that maybe he's feeling guilty, because he did. And so, all jokes aside or funny stuff aside, there is a very real connection for the ancient Egyptians between the living and the dead. And so he wrote a letter to her, placed that letter in her tomb attached to a statuette of her. And so, yeah, interaction, probably, in the minds of the Egyptians, existed.

Yeah. And also in a good way. Right. And the ancient Egyptians, as I said, they would visit the tombs of their deceased. They would bring offerings to them. We know that for certain periods they would also have, either close to the household or in separate chapels, a statuette of ancestors that they could talk to, that they could interact with, that they would bring offerings, again in the hope that they could act as intermediaries, sort of like those animal mummies, between the living and the gods.

So having someone in the spirit world, in the world of the gods is also a good thing. They can help you out. But they apparently can also bother you.

Craig Middleton: Thank you so much, Daniel. That deserves another round of applause.

<applause>

It's actually quite a privilege to have Daniel here. Only in the country for four, maybe four and a half days, to share his knowledge and expertise with us, and the knowledge and expertise of the museum in Leiden. And if that didn't entice you to grab your ticket to the exhibition, I don't know what will. But I think, you know, what you get a sense of, not only from what Daniel spoke about, but also the questions that were coming from the audience is that the show is about ancient Egyptian culture, but it's also about the practice of archaeology and engaging with, you know, a lot of the behind-the-scenes work.

And on top of the exhibition, there is a publication. I've seen and some of you have it. Downstairs. So if you want to learn more about the Leiden Museum, if you want to learn more about the conservation techniques that they use on some of the coffins and some of the objects that are in this exhibition, please grab a copy of that because there's some beautiful essays that accompany the catalogue in there. So, thank you again, Daniel, and thank you everyone for coming.

<applause>

More Episodes

John Mirosevich explores the varied history of Thonis-Heracleion, Egypt’s greatest Mediterranean port for 400 years.

Listen to Hon Dr Anne Aly MP who joined us at Afterlife Bar for a presentation on the Discoveries of Ancient Egypt exhibition.

Join committee members of The Ancient Egypt Society of WA Inc for a unique opportunity to dig deeper into Egyptology.

Dean Kubank revisits the Temples of Nubia and the enchanting Temple of Isis at Philae.

Celestial Timekeeping in Ancient Egypt - Discover how Ancient Egyptians used the heliacal rising and setting of stars to construct their star clocks and civil calendar.

The life of the average Egyptian could sometimes be precarious and short. Broken bones, infections, and arthritis were all common among the general population.

Discover the story of the pharaoh Djedkare, his family and courtiers, and take advantage of the rare opportunity to hear from visiting international Egyptologist Dr. Hana Vymazalová of Charles University, Prague.

Discover the story of the pharaoh Djedkare, his family and courtiers, and take advantage of the rare opportunity to hear from visiting international Egyptologist Dr. Mohamed Megahed of Charles University, Prague.

Discover Egypt’s ancient legends of creation, death and resurrection. Tales of Ra, Osiris, Isis and Horus will unlock the meanings of the art, religion and funerary practices of ancient Egypt.

The Dynasty 6 Vizier named Weni the Elder, who lived about four and a half thousand years ago, had a detailed biography written on the outside of his tomb.

How, when and why was mummification invented? The answers may surprise you.

Ancient Egyptian Astronomy Unraveled - Discover how the Ancient Egyptians used their knowledge of the sky to design and position their temples, statues, and roads.

As part of our evening Afterlife Bar series at WA Museum Boola Bardip, we welcome a series of speakers to dive deeper into Egypt. Join us this week as we hear from Dean Kubank on Temples and Tombs.