Connecting Modern and Ancient Egypt by Hon Dr Anne Aly MP

Born in Alexandria, Hon Dr Anne Aly MP moved from Egypt to Australia with her family at the age of two. In her late twenties, she was a single mother of two young boys, relying on minimum-wage work and social services benefits to put food on the table. She went on to study her Masters and PhD and worked as an academic, professor and practitioner in counter terrorism and countering violent extremism. Anne was the only Australian representative to speak at President Obama’s 2015 White House summit on countering violent extremism. Anne has been the Federal Member for Cowan since 2016.

In 2021, she was awarded the McKinnon Prize for Emerging Political Leader of the Year in recognition of her Parliamentary work against both right-wing extremism and family & domestic violence. Following the election of the Albanese Government, Anne was appointed Minister for Early Childhood Education and Minister for Youth – becoming the first Muslim woman to serve as a Commonwealth Minister."

-

Episode transcript

Intro:

Welcome to the Western Australian Museum Boola Bardip talks archive. The WA Museum Boola Bardip, hosts a series of thought-provoking talks and conversations, tackling big issues, questions and ideas and is delighted to be able to share these with you through the talks archive. The talks archive is recorded on Whadjuk Nyoongar Boodja. The Western Australian Museum acknowledges and respects the traditional owners of their ancestral lands, waters, and skies.

Alec Coles:

Good evening, everybody. Thanks so much for coming out on a Friday night and welcome to WA Museum. Boola Bardip. My name is Alec Coles. I'm the CEO here at the WA museum and I always begin on occasions like this by acknowledging that we meet on Whadjuk Nyoongar land and pay my respect to Whadjuk Elders past and present, and note that this was a really important place for Whadjuk, people of a deep history, a place where there was a wetland where people would meet and fish, and hopefully we’ve reflected that in the way that the museum has developed here. It is my great pleasure, and I'll say it again to welcome not only a very special guest, but a bit of a, bit of a political hero of mine this evening, Dr. Anne Aly MP. Anne as I'm sure most of you know, has been federal member for Cowan since 2016 and following the election of the Albanese Government and was appointed Minister for Early Childhood Education and Minister for Youth, becoming the first Muslim woman to serve as a Commonwealth Minister in Australia In 2021 she was awarded the McKinnon Prize for Emerging Political Leader of the Year in recognition of her parliamentary work against both right wing extremism and family and domestic violence. Long before that, Anne had an extremely distinguished career as an academic professor and practitioner in counter-terrorism and countering violent extremism. In 2016, she was nominated for Australian of the Year and also received the prestigious Australian Security Medal for her work on deradicalisation focused on Muslim identity and activism. She is a founding chair or the founding chair or I should say, of People Against Violent Extremism, Australia's first non-government organization to combat violent extremism. She was appointed a member of the WA Women's Hall of Fame in 2011, the first Hall of Fame intake, and in 2014 she was named one of Australia's most influential women by Westpac Financial Review. We were talking beforehand and she said, “Oh, I'll just do as I'm told.”

I said, “You're probably the last person in the world who would do as they’re told.” But anyway, that's her autobiography, “Finding My Place”, published in 2018, boasted the strap line: “From Cairo to Canberra, the irresistible story of an irrepressible woman.” And that's exactly what she is. And it's also the clue as to why she's here tonight, not to talk politics particularly, but to talk about the land of her birth, Egypt, as part of a series of events supporting the Discovering Ancient Egypt exhibition. And I said to the first group this evening, I first became aware of it. And when she appeared on Q&A and she was, I have to say, by far the most interesting and inspirat…inspirational actually member on the stage. And as I said, given that I'm the only competition tonight, she's pretty much assured of that as well this evening. So would you please join me in welcoming Dr. Anna Aly.

Audience:

*Applause*

Alec Coles:

So Anne, you were born in Egypt and I'm not even going to… I did have a really pathetic attempt to pronouncing your, your name and then you corrected me, so I think you'd better do it.

Dr Anne Aly:

So my birth name is Azza Mahmoud Fawzi Hosseini Ali el Serougi.

Alec Coles:

I said, I said nothing like that at the time, so…

Audience:

*laughter*

Dr Anne Aly:

Completely wrong

Alec Coles:

I did, I did, I hope it wasn't offensive. Whatever….

Dr Anne Aly:

No not at all.

*Alec Coles continued to speak in the background but audio was unclear*

Alec Coles:

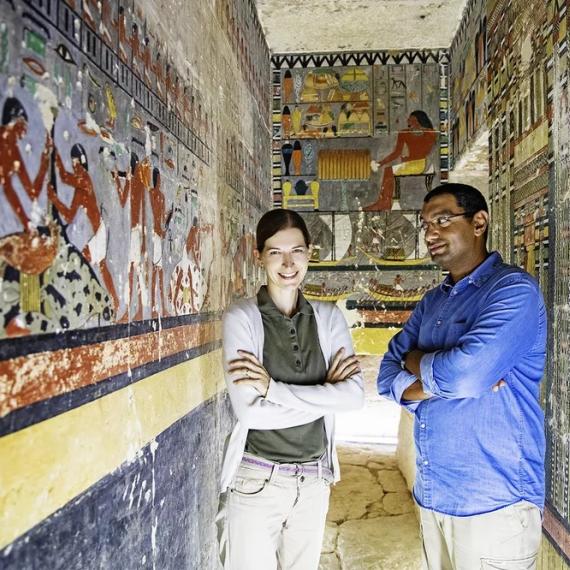

….. but there we go . But you left when you were only two. But you did go back to live there for I think, five years. And you also, and this, I didn't know this he was speaking earlier. You study the of the American University in Cairo in archaeology. So very well equipped to speak here this evening. But I kind of wondered how much of a sense of, I guess, belonging you feel with contemporary Egypt? and to what extent you feel connected to ancient Egyptian culture?

Dr Anne Aly:

Thank you, Alec. It's wonderful to be here for the second time this evening. And good evening, everybody. It's wonderful to join you. Join you here. Yeah. I was born in Egypt. And interesting to note that my the first language that I ever spoke was not English, it was Arabic. But by the time I was seven years old, I had forgotten all my Arabic and only spoke English. So I kind of I went back to Egypt after I finished high school, and that was kind of to kind of reconnect with my identity and my, my cultural and traditional history. And it was a really seminal moment and time in my life as a young adult at that point, because like many young adults, I was questioning my sense of belonging and questioning an identity, especially as an ethnic in Australia growing up in the seventies, where I stood out like a sore thumb and, and never quite feeling quite Australian, and then going to Egypt and thinking, okay, yeah, this is where I belong, this is my people, this is my, this is where I was born. But then going to Egypt and feeling very much like a fish out of water there as well, because I discovered there that I wasn't Egyptian in, in any, you know, apart from birth and cultural and traditional heritage. And I spent years in Egypt trying to reconnect, to try and reconnect with that and get that kind of sense of identity and sense of who I am and where I belong and and a balance in my life between my cultural and traditional heritage and my home, which is Australia, and where I've always felt and called home. Um, I don't know if any of you can say, but I wear a Nefertiti around my neck. And there's a number of reasons for that. The first is that my husband and I had this made and it's embossed with some stones that we had melted down from some jewelry that we had to represent my past, our present and our future together. So it's got quite significant sentimental value. But the other sentimental value that I hold for Nefertiti is that she actually lived in what is now the governorate of El Minya, which is about 200 kilometers south of Cairo, which is where my mother is from, and where much of my extended family still lives in El Minya. And so I've always kind of felt an affinity to Nefertiti. She was the wife of, of, of a king and she actually installed some great reforms in Egypt, particularly religious and social reforms. But she's not well, well known except for that beautiful bust of, of, of hers and that that that beautiful carving of her. But I've always been and fascinated and felt an affinity to Nefertiti. So I guess you know many, many decades on I've kind of come to a space where I very much identify as Australian and, you know, this is my home, this is my, my country and I have a deep, deep loyalty to Australia and her people. But I'm deeply also connected to and deeply proud of my Egyptian heritage and, and, and that connection also to the history of my heritage in ancient Egypt.

Alec Coles:

So do you think, I mean, I guess a lot of people will be aware of your Muslim faith, but maybe not so aware of the Egyptian connection? I just wondered to what extent they are. And, you know, as you grew up. Were their aspects of Egyptian culture and even ancient Egyptian culture that fed through your family, that would have actually revealed that to people?

Dr Anne Aly:

Um, Yeah. Look, growing up, I think like like all young people at school, we learned about the pyramids and we learned about mummies. And I'd be like:

“Yeah, that's my people. Ahum,That's my granddad right there *laughs*

So there was that. And I think like there is a quite a significant Egyptian community in Australia. And so they all recognize that I'm Egyptian, but the funny thing is no matter where I go, people think I'm from there. So I went to Spain and people were coming up and speaking to me in Spanish. I'm like, “ehh no esta habla espanolo”. I went to Italy and people thought I was Italian. People think I'm Brazilian, people think I'm Indian. If I went to India, people thought I was Indian, I went to Pakistan, People thought I was Pakistani. I'll go to Egypt and people go, “You? you're not Egyptian, you don't look Egyptian”. So, um, so yeah, there's that there's a but certainly, um, you know, I am, I am of course very proud of my Egyptian heritage. So I talk a lot about my Egyptian heritage and whenever I go and visit schools and you know, we talk about how multicultural Australia is and I say to the young people, I say “guess where I'm from”, and they all look at me and I say, it's a country where there are pyramids and they go, you're from Egypt. So it's always quite nice to have that, like, that young people like children know about Egypt through the pyramids and through that connection and that learning about ancient, ancient Egyptian history.

Alec Coles:

I guess this evening's session is really about the connection between contemporary and ancient culture. I like to think, I hope, that the WA Museum Boola Bardip in presents Aboriginal cultures as contemporary.

Umm, too often in the past, museums have actually, you know, shown old artifacts. And it's almost as if Aboriginal culture is a past culture, which of course is not. And I just wondered, to what degree, ah, you know, I guess Egypt has that uh, the, the I suppose the myth and the reality of ancient Egypt has that impact on contemporary Egypt and how people maybe conflate the two, confuse the two.

Dr Anne Aly:

I don't think there is. I mean, one of the things that struck me when I, when I lived in Egypt was that modern day Egypt and contemporary Egypt is very much shaped by contemporary politics and geopolitics. You know, Egypt has been invaded and, and occupied by French and British along the way. But modern Egypt is very much Arab-ized and, you know, in the 1950s, you had the free officers revolution where they expelled the monarch, but it also expelled a lot of the multicultural communities, the Maltese and the Greeks out of, out of Egypt and particularly out of Alexandria, which is where I was born. And that really changed the complexion of the society in the big cities in Cairo and Alex and some of the other big cities, because it resulted in an influx of people moving from the rural to, to, to, to the cities and really changed the face of the cities there. And then you had pan-Arabism and this kind of promise of Egypt being, being part of this, um, you know, Arab collective, if you like, that was a collective by virtue of the fact that we spoke Arabic language, but, culturally similar but not the same. And the broken promise of that delivering more for the people of Egypt. Then, of course, you had various wars in 1967. In the 1970s, you had wars. Then you had, you know, military rule. And then we all remember the Arab Spring. And contemporary Egypt is really shaped by these contemporary political movements and geopolitical movements in Egypt. But despite that, despite that, when you look at Egypt's place, modern Egypt's place in the history of the Arab world and in the history of that geopolitical situation, it has always been the seat of culture and art. Some of the most famous Arabic poets, Ṭāhā Ḥusayn and Naguib Mahfouz, eh, Arabic poets and writers are Egyptian. Egyptian cinema, was renowned among all of the Arab world, and I often, when I meet people from Lebanon or Iraq, they say, we can speak Egyptian because we watch Egyptian cinema. We can speak, we understand your tongue because we watch Egyptian cinema. And so there is this thread of culture and art. And Egypt, of course, was where we had the start of Arab feminism with Huda Sha'arawi. She was Egyptian. She stepped off a train in Cairo and she removed her face veil and led to a wave of women across the Arab world, removing their face veil and fighting back against the Harem system, which had women veiled and kept in the dark, eventually leading to Egyptian women and then other Arab women getting the right to vote. So there have been all of these movements in Egypt, have been this this hub of culture and art that really speaks to its connections to ancient Egypt. And to, eh, to that, that, that, that, that, I guess, the, the craft and the art and that, the kind of the humanities, the focus on the humanities that kind of has moved through the ages there.

Alec Coles:

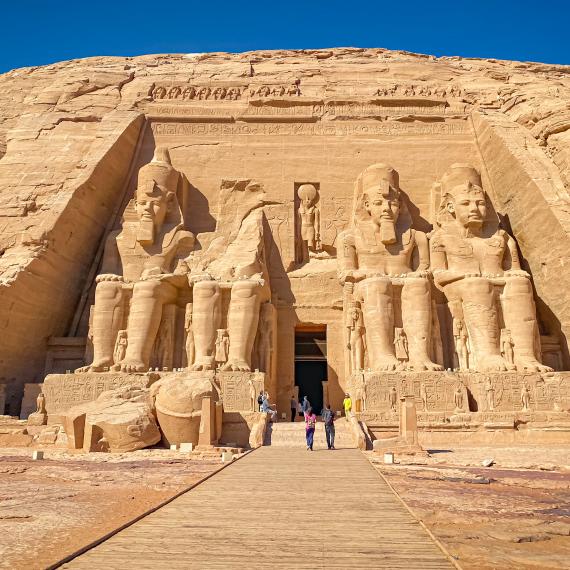

Yes. I wanted to talk, and I mean, really around the exhibition and the impact. So Discovering Ancient Egypt has come, you know, some say bizarrely enough, from the Netherlands. It’s actually from the Rijksmuseum Van Oudheden and I know they would want me to point out that that this is not stolen material. This is material…. *cut of by Anne Aly’s response*

Dr Anne Aly:

I checked, its not stolen.

Alec Coles:

..thats right…

Audience:

*laughs*

Dr Anne Aly:

Before I agreed to do this.

Alec Coles:

Exactly, Before we agreed to take it as well. This was material that was gifted by the Egyptian government to the Rijksmuseum Van Oudheden in recognition of decades of joint excavations at Saqqara and that's how it came there. However, there is no question that the Western world has long been intrigued and fascinated and, in some cases, obsessed with ancient Egyptian culture. And Western museums are full of Egyptian artifacts and let's be honest, human remains, as indeed this exhibition has. And I just wondered how you felt about that appropriation of ancient Egyptian culture, Egyptian culture, and to what extent maybe it does blind us to our understanding of modern Egypt.

Dr Anne Aly:

I have mixed feelings about it because on the one hand there is that there is, there is a lot that was stolen. When you imagine the pyramids, if any of you have seen the pyramids, the pyramids that you see today are not how they were when they were first built. There's been a lot of pillaging of Egyptian artifacts, Egyptian riches, gold and, and, and very precious artifacts as well. And I was just reading about the bust of Nefertiti. There was a huge thing to, to for Germany to give it back and the Germans, the Germans refused. But I also noticed going through the exhibition here that a lot of it was gifted by the by the Egyptian government. And it in a sense, you know, there's a whole temple there from Sara that was gifted. And I feel like, yeah, we've got enough temples here, you can have one. But yeah, and I feel that the other side of it, though, is that, you know, I've been blessed that I've been able to visit Egypt on several occasions and I meet so many people every day who go, “I would love to go there, it's on my bucket list”,

You know, fascinated by it. I would love to go there. So in a sense, I'm really grateful that we can bring ancient Egypt to the people, because this is not just Egyptian history. It's human history. And we all share in that human history. And I think that that's a much more positive way of looking at it. Do I despair that some of it was stolen and taken? Yes, absolutely I do. But I also acknowledge the gift of bringing ancient Egypt to the people as part of a shared human history.

Alec Coles:

It's a really interesting question in that, you know, on the one hand, should everything go back from whence it came or actually do we learn much more by being able to share culture with each other? You know, there's no right answer to this.

Dr Anne Aly:

Well, if it, if it went back to when it came, you know, the old Egyptian museum had five floors underground where they housed things that they just did not have the room to show, which is why they built the new museum out at Giza, because there is so much and we're still discovering new things. Like it was just in 2019 and 2020 they were discovering new things in El Minya, and they're still discovering new things every day. So there's also the capacity of Egypt itself to hold as many artifacts as there are.

Alec Cole:

When you were talking about Nefertiti, and I remember seeing that bust in Berlin, actually, it's, it's an incredible piece, but, and, you know, you did mention really that she played an important part in your hen night, actually, and which you might want to talk about in a moment.

But I, I, because, again, this fascination is, has been, I guess, magnified and repeated through the use of ancient Egyptian iconography and symbols in contemporary culture as so many great examples. I, my, my favorite, always incredible figure that comes in the dream sequence in Fritz Lang’s film, Metropolis. But you see it everywhere, you see in architecture and art. And I just wondered, you know, if you had any sort of, apart from the, the hen night, the favorite examples of how that's been repeated? or I think you were saying earlier, you know, your interest is more, I guess, in the factual side of the… Yeah,

Dr Anne Aly:

it's just the hens night thing is that for my hens at night the theme was ancient Egypt. So I got to dress up as Nefertiti. But don't expect any photos.

Alec Coles:

We want the photos, yeah, we want the photos

Audience:

*laughs*

Dr Anne Aly and Alec Coles:

*Laughing*

Dr Anne Aly:

He's got em. He’s got em!

Alec Coles:

He's got the photos! Yeah

Dr Anne Aly:

That’s my husband.

Alec Coles:

You catch him later.

Dr Anne Aly:

I think. I think you're right. Like there has been a lot of pop culture around ancient Egypt, but it's actually been very selective. Like there's been a huge fascination with Cleopatra and the story of Cleopatra and, you know, it's a compelling story. She falls in love with Mark Antony. There's a snake involved. I don't know, whatever. She really actually married her brother, that's the truth of the story. But it's very much been westernized. The story's been westernized and, and shown in, in, in Hollywood movies and, you know, every glorious and um, glorious Hollywood actress had to somehow identify that in a past life she was Cleopatra. They all had a fight over who was Cleopatra in a past life. So there's been a lot of focus on Cleopatra, but there are so many other female figures like Nefertiti, who was the wife of Akhenaten and the, the, the kind of the social changes that they made to, to that era and to the place. I mean, he changed the capital to El Minya, to Akhenaten. So, so there are, there are a lot of other figures in there. I guess for me the kind of the, the stuff that I kind of connect with isn't so much the movies or the, or the pop culture because they all seem a little bit fake to me, to be quite honest. Like, you know, putting Joel Edgerton in a movie about ancient Egypt and giving him a bit of, you know, Bondi, Bondi beach tan to make him look Egyptian. I mean, come on. But, um so for me it's more like, like, for me, it's more like, you know, the first time I saw the pyramids or, you know, the the, the, the, the real life experiences and the real life connections with parts of ancient Egypt. Watching the documentaries. You know, I went and visited the new library in Alexandria when it was new. And did you know that as they were excavating for that library, they found so many artifacts that they actually had to redesign the library and build a museum to house the artifacts that they found. Like, it's mind blowing that they are still finding new things every day. And then the other thing is, wherever you go in Egypt, like you go to Giza, which is where the pyramids is, and you go to Alexandria, where I was born, and they've got such a different complexion in their histories. Alexandria, very much a Greek influence in the history and, you know, Greek mosaics and very much a Greek influence. And then you compare that to Ta-pe, which is the English is Thebes or Menfe, which is Memphis. So for me, it's more like the, the kind of the lived experiences of it, but also the factual stuff that, the stuff that's not all gloss and glamor and Hollywood that gets me, I guess.

Alec Coles:

Fair enough. And that, that point about the sort of Westernizationing, and I was saying earlier, the, if you've been through. Just like every exhibition which has mummified people in, there is a cat scan, there's a reproduction of a face from one of the mummified people, which was devised from a CAT scan. And I have to say, this has been done so many times and everyone looks the same. And, and, as, I remember in the UK years ago and one of the newspapers that was in the tabloids pointed out that it looked like Cher and they and they all look like Cher…

Dr Anne Aly:

Well wait for one to look like me.

Alec Coles:

*laughs* Well, maybe we should work on it. But there's a quite a lot of controversy about how, you know, that sort of, you know, the methodology they use is still based very much on kind of Western, white features.

Dr Anne Aly:

Western geneology

Alec Coles;

Yeah, exactly. Anyway, look, I. I can't see anything because of that light in my face, but there is, I think somebody with a microphone out there. So do we have any questions for and from the audience.

There's a. Yes, there's a hand there. Thanks.

Audience member 1:

Hi. Thank you. Thank you. I think you're amazing. I'm going, I'm off to Egypt in six weeks.

Dr Anne Aly:

WHAAAT! WHOOOOO Everyone give her a hand!

Audience:

*Cheers*

Audience member 1:

Got some advice?

Dr Anne Aly:

I've got so much.

Alec Coles:

*laughs* She's got so much advice

Audience member 1:

Three points. Three, three top points.

Dr Anne Aly:

So are you going to Cairo?

Audience member 1:

I'm going to Cairo, Aswan, Luxor…

Dr Anne Aly:

Have you booked your hotel yet?

Audience member 1:

It's a it's a tour through G Adventures. Yes.

Dr Anne Aly:

Okay. So you're, ok, so you don't get to book your own hotel?

Audience member 1:

No, unfortunately.

Dr Anne Aly:

Booooo, okay, my advice to anyone going to Egypt at the Mena House Oberoi. And I will tell you why. The Mena House Ob… not because I get kickbacks there, I don’t…

Audience member 1: I’m not staying there. What should I eat and um…?

Audience:

*laughs*

Dr Anne Aly:

Oh, okay, eat! Eat everying! Everything's good now. But like, don’t eat like, like if somebody offers you like, Koshary, or Ful medames, this very cheap food like get some of the good stuff I'll tell you

Audience member 1:

I was told today to eat Koshary.

Dr Anne Aly

Yeah, but Koshary is all carbs. It's like rice and pasta and *inaudible as the audience member responds*

Audience member 1:

I'm going to need carbs. There's a lot of walking involved.

Dr Anne Aly:

Oh ok then, eat the carbs, eat the carbs, Honey, you can afford it. I mean, if anyone is going to Egypt, stay at the Mena House, Oberoi in Giza. It overlooks the pyramids. And I'll tell you why I recommend this place, because we went and stayed there. Now, the Mena House Oberoi was even was originally built as a homestead. It was extended to accommodate a visit by Princess Eugenie. But you walk into this hotel and it's, you open up your window and there's the pyramids, right? You open up your curtains, there are the pyramids. But you look around and there's all this Australian history, everywhere you go, Australian history. And it's because it housed our Anzacs in World War Two. And I got to tell you how surreal it is to walk into a hotel room, look out the window, and there are the pyramids right in front of your face, and then look around and see home and see this connection to home. It is a deeply, deeply profound experience for Australians to stay at that hotel. If you do go. The general manager, his name is Mohamed mentioned my name. I'll give you a good price.

Audience member 1:

Mena, Mena House what?

Dr Anne Aly:

It's very, very… *laughs*

Alec Coles:

And it was worth coming this evening just for that.

Audience member 1:

Thank you

Dr Anne Aly:

It’s not pricey. You'll be fine. Eat, eat, Warak enab, Malfuf. Dave translate for me.

Alec Coles:

*laughs*

Dr Anne Aly:

What the ah, the Dolmades, but the, the, the Egyptian kind, they're much nicer.

Alec Coles:

*inaudible*… vine leaves… *inaudible*

Dr Anne Aly:

Oh! If you go to Khan el-Khalili, my God, I've got to tell you all this. If you go to of Khan el-Khalili White, wait, cause this is such a good story! If you go to Khan el Khalili near like, theres this alabaster shop right. But near the alabaster shop you'll see this old wooden door. Right. And you will think that it's so scary to walk through that door. But walk through the door. It is the Taha Hussein Cafe and you walk through the door and it is this huge cavern of people playing Egyptian music, people sitting around smoking shisha, waiters walking around with these huge platters of food with the Tarboursh on it is like you have walked into.. back into history. It is amazing. Amazing. Find it It's called the Taha Hussein Cafe at Khan el-Khalili. But it's deep, deep, deep, deep, deep in Cairo. At the market. It's deep in the markets. You have to find it. You have to look for it.

Alec Coles:

Fantastic, fantastic. Do we have any more questions about ancient Egypt or where to stay when you go there?

Audience:

*laughs*

Audience member 2:

Um, yeah, I also think you're amazing, but this is going to be hard to phrase. So, you've talked about how, you know, there's this Hollywood version of Egypt where they tend to focus on Cleopatra. And certainly I think, in the Western world, we tend to emphasize certain, you know, figures like, okay, most people know of Hercules. Most people will know the story of like Little Red Riding Hood. Within Egypt, are there any figures from ancient Egypt that are sort of often represented as like symbols in modern Egypt?

Dr Anne Aly

Absolutely. So some of you will know the, the, Ramses the second. There was a huge statue of Ramses, the second which stood over Ramses Square. It was installed in Ramses Square by Gamal Abdel Nasser when he became the president of Egypt and it stood there for some 50 years. In 2006, they moved the statue from Ramses Square because of the pollution was having a negative impact on the statue.

Now, I, um. I attended the American University in Cairo, which was like this oasis in the middle of bustling Tahrir Square, which is right next to Ramses Square, which is where the Cairo train station is. And so that figure of Ramses, like over that the this this bustling city was such iconic, it was so iconic of Ramses Square and the center of Cairo.

When they moved the Ramses, finally moved his statue because they moved it to the new museum, but also to preserve it. The streets were lined with people who were in tears, who were crying because they had felt such an affinity to Ramses, like he had stood over them for all of these years. So there is certainly that connection to Ramses. In El minya, where, where I mentioned where my mother is from.

As you drive into El minya, there's a huge statue of Nefertiti and there is this like, This is the birthplace of Nefertiti, Welcome to the, the birthplace of Nefertiti. There's the Nefertiti hotel, which I wouldn't recommend.

Alec Coles and Audience:

*laughs*

Dr Anne Aly:

But don't tell them I said that. And so there is there, there is that kind of connection there. Funnily enough, I've never seen Cleopatra portrayed in any Egyptian movies, never seen her portrayed in any Egyptian movies.

Might have something to do with the fact that she was Ptolemaic. Um, but yeah, but there have been like Egyptian stories about those lesser known, to the Western world, lesser known figures in Egyptian, ancient Egyptian history.

Alec Coles:

I think there was a hand… we have time for one more question. There’s a hand about four rows back here. Thank you.

Audience member 3:

Hello, As someone who doesn't know much about more of the modern Egypt culture, how would you say… what would be your advice, as someone like myself going into an ancient Egyptian exhibition exhibition, how do I tie ancient Egypt to modern Egypt without much background knowledge?

Dr Anne Aly:

Wow, that's a great question. I think that, I think to understand that there is a bit of a disconnect between ancient Egypt and modern Egypt. Modern Egypt is very Arab-ized and it has a lot to do with pan-Arabism and as, it has a lot to do with the kind of the influence of the gulf nations and, and the Islamic revolutions in, in,, in in the Arab world and in, in Egypt.

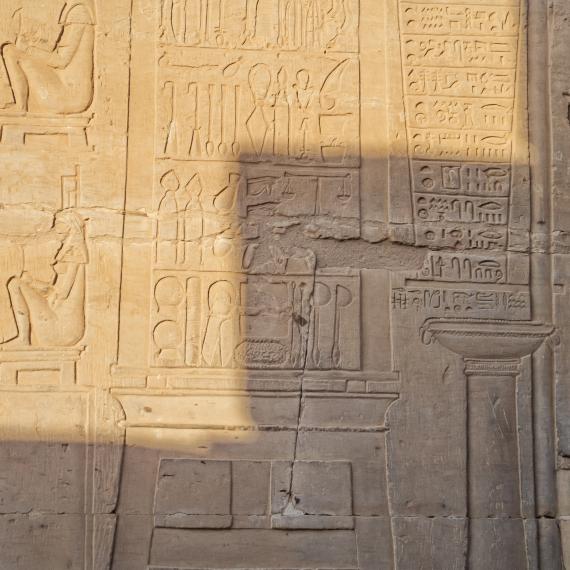

But, you know, I think there is also a lot there. And I'll give you, I'll give you a really good example. In, in the exhibition here, there's um, in the exhibition about the Book of the Dead, there's a manuscript there about when you die and your heart is weighed up against the feather. And if your heart weighs more than the feather of good, then you, you get, you go to the nice place, the good place and if your heart weighs less than the feather of good, you go to that horrible place. That's an ancient Egyptian theol… their belief system, their theology. Modern Islamic theology, we have the same concept that when you die, your good deeds and your bad deeds get weighed on a scale. And if your good deeds outweigh your bad deeds, you going to the good place! If your bad deeds outweigh your good deeds, you're not going to the good place. You're going somewhere else. So there is also, like even in the spirituality and in the belief system, there is a connection there. So I think, you know, it's like, umm, it there is that that kind of understanding of modern Egypt being a product of, of contemporary geopolitical events. Right? But also, understanding also that the Egyptian people are incredibly, incredibly proud of ancient Egyptian history and of their ancient Egyptian heritage. Umm, and I think that that is a long a long standing and sustained source of identity and pride in identity for the Egyptian people today.

Alec Coles:

Thanks Anne. Look that we, we are at a time. So you all knew what an impressive politician she was.

You probably didn't know how knowledgeable she was about ancient Egyptian history and iconography and archaeology. You now know that she has a future career as a travel agent.

Audience:

*laughs*

Alec Coles:

So will you please join me in thanking Dr. Anne Aly for a wonderful…. *the rest of the sentence is drowned out by audience applause.

Outro:

Thanks for listening to the talks archive brought to you by the Western Australian Museum Boola Bardip. To listen to other episodes, go to https://visit.museum.wa.gov.au/episodes/conversation where you can hear a range of talks and conversations. The talks archive is recorded on Whadjuk Nyoongar Boodja. The Western Australian Museum acknowledges and respects the traditional owners of their ancestral lands, waters and skies.

More Episodes

John Mirosevich explores the varied history of Thonis-Heracleion, Egypt’s greatest Mediterranean port for 400 years.

Join committee members of The Ancient Egypt Society of WA Inc for a unique opportunity to dig deeper into Egyptology.

Dean Kubank revisits the Temples of Nubia and the enchanting Temple of Isis at Philae.

Celestial Timekeeping in Ancient Egypt - Discover how Ancient Egyptians used the heliacal rising and setting of stars to construct their star clocks and civil calendar.

The life of the average Egyptian could sometimes be precarious and short. Broken bones, infections, and arthritis were all common among the general population.

Discover the story of the pharaoh Djedkare, his family and courtiers, and take advantage of the rare opportunity to hear from visiting international Egyptologist Dr. Mohamed Megahed of Charles University, Prague.

Discover the story of the pharaoh Djedkare, his family and courtiers, and take advantage of the rare opportunity to hear from visiting international Egyptologist Dr. Hana Vymazalová of Charles University, Prague.

Discover Egypt’s ancient legends of creation, death and resurrection. Tales of Ra, Osiris, Isis and Horus will unlock the meanings of the art, religion and funerary practices of ancient Egypt.

The Dynasty 6 Vizier named Weni the Elder, who lived about four and a half thousand years ago, had a detailed biography written on the outside of his tomb.

How, when and why was mummification invented? The answers may surprise you.

Ancient Egyptian Astronomy Unraveled - Discover how the Ancient Egyptians used their knowledge of the sky to design and position their temples, statues, and roads.

As part of our evening Afterlife Bar series at WA Museum Boola Bardip, we welcome a series of speakers to dive deeper into Egypt. Join us this week as we hear from Dean Kubank on Temples and Tombs.

Renowned expert in ancient Egyptian history Daniel Soliman delivered a fascinating talk, as we celebrated the launch of the WA Museum Boola Bardip's Discovering Ancient Egypt exhibition.