Death & Disease by Dr Alanah Buck

The life of the average Egyptian could sometimes be precarious and short. Broken bones, infections, and arthritis were all common among the general population. This was a world where even a toothache could result in death. Dr Alanah Buck is the State Forensic Anthropologist with the Dept Forensic Pathology, PathWest. Since 2004, Alanah has been a member of the Australian Centre for Egyptology Fieldwork Team (Macquarie University NSW) and has travelled many times to Egypt to assist in excavations and the examination of human remains.”

-

Episode transcript

Event MC: Good evening, everybody and welcome to the WA Museum Boola Bardip and the Discovering Ancient Egypt exhibition. Before we get started with our guest speaker for this evening, I would just like to take a moment to acknowledge the lands on which we are gathered on and learning here today, the lands of the Whadjuk people of the Nyoongar nation. May we pay our respects to their elders past and present.

Today we have a very fascinating speaker, Dr. Alanah Buck. Presenting a very wonderful talk on the disease, well wonderful? Sure! Disease and death in ancient Egypt. Please enjoy.

(applause)

Dr Alanah Buck: Okay. Thank you. Can everybody up the back? Is that okay? Everybody can hear sufficiently? Great. I won't yell then. Well, thank you very much for the kind introduction. I'm not sure about the wonderful so much, but hopefully it's interesting for everybody this evening. I've spent quite a bit of time in Egypt. I actually work there in my holidays. So, it’s a bit of a busman's holiday for me but I’ve been a number of times.

I’m a member of an archaeological, Egyptological team from Sydney. And we excavate in Luxor and Saqqara, and I'll show you some, some pictures from there tonight. And it's my role to be the physical anthropologist. So, I examine the bodies, the mummies, the bones, all of the people part. So, it's no good asking me questions about mythology or hieroglyphs, because as my team can attest, I know nothing about it. But I will try and answer questions as best I can.

So, this evening's talk, as you can see from the title, is, is really about some of the commonplace things that you find in Egypt for people, their health, disease, death. Obviously, we're here in the Afterlife Bar tonight, so that's probably very appropriate given how important it is or was for the Egyptians. How that sense of moving into the afterlife was so... preserving their bodies, and I'm sure many of you know all about mummification. But what a lot of people perhaps don't know quite as much about is the health properties and things that happen to the average person in Egypt.

So. Let me get used to the technology. Nope the first one doesn't work, of course. Hang on. The clicker is not exactly (inaudible) I'll just go manual. How’s that? I'll go manual. Alright. It's not a talk unless the technology fails first up. So that's, we've got that one out of the way hopefully. Yes.

So, as I say it's, it's kind of ironic we're here talking about this and we're in the Afterlife Bar and how important this was to the Egyptians. So, death clearly wasn't the end of the process for them. Death was the step before the afterlife. And so much was done to prepare for this. And how they prepared the bodies and how they prepared themselves. So, we'll be looking a little bit at that this evening.

As I say, I'm no expert on the gods or any of the other Egyptian mythology, unfortunately. But one god that I am fairly familiar with is of course Anubis. And Anubis I’m sure everybody here has heard of, knows something about. And he was the God of protection and death. And he played a huge role in the transition of people into the afterlife, weighing of the heart and things like that. He also was a god of protection and oftentimes you will find in some of the tombs we've excavated, in the graves that I’ve excavated, there are amulets of Anubis because he was there to protect the body. And this is in with the ordinary folk, not just the nobles and the royalty, protecting their remains so that they would be preserved. So, when they got to the afterlife, they would be in good condition. So, he's a very important player in this.

So how did that translate into everyday life for people? Well, we're pretty au fait. I think everybody understands the Egyptian mummies. Very famous, the mummification processes. And that's how important it was - for the eternal form to be preserved so that it could pass into the afterworld, the underworld, and continue on, continue on forever. And I guess in many ways that's exactly what they've achieved, because we're standing here tonight, 2000, 3000 years later, and we're still talking about these people. So, in many ways they have achieved the afterlife, perhaps not quite in the way they’d anticipated, but we are still looking at them. We're, we're looking at their faces and we're marvelling at what their lives must have been like.

And of course, most of us are pretty familiar with many of the famous mummies. So we have here - sorry, I won’t move away. Thutmose the third and Amenhotep. And these were important pharaohs, obviously. So, the way pharaohs and royalty and nobility were preserved and mummified is obviously quite different to what the situation for the average person was. So, there was the deluxe work, and then there was the sort of ordinary work, and then there was the dodgy brothers at the end. And you can see very clearly and oftentimes I look at some of the remains and think, well, I hope they didn't pay very much for this one. So, but in general, the mummies beautifully preserved. The arm position, of course, tells you something about the, the royal-ness of the of the individual. Many of them, unfortunately, haven't survived very well into modern times because of the grave robbing. And also, in in 100 years ago, more mummies were often used for all sorts of things as well as being sold around the world as curiosities.

So many of them have had a bit of a rough life after they were originally interred. So you can see here some of the names of the famous individuals. Ramses the second, of course, I think everybody recognizes him and Ramses III. And he, of course, was the model for a lot of the Hollywood horror movies that introduced mummies to a new generation of people. I'm not sure why he was chosen in particular. I guess he's pretty well preserved, but he seemed to be one of the poster boys.

And then, of course, I think everybody would agree the most famous of all, the ancient Egyptian pharaohs. He was also one of the most insignificant. So, I guess he's done very well in the afterlife. Managed to become the most famous of all, outranking even Ramses, Thutmose, and Amenhotep, who were much more important pharaohs, obviously in Egyptian history. But this guy had the good fortune to not get robbed. Which meant we had a snapshot of what a royal burial would have looked like. And of course, for everybody, everybody likes gold. Everybody likes gold. Seeing the gold, it's amazing. If you get a chance to go to Egypt and those of you here who've already been obviously know, the royal death mask is absolutely amazing. There's a lot of things you'll read about and see on TV and then you go and visit and you think, ah yeah, that wasn't so bad. But this will never disappoint. It is incredible, the craftsmanship.

So, he was a, he was an 18th dynasty pharaoh. He died. He was a very young individual when he died. It's a bit difficult to say exactly how old he was, but somewhere between about 18 and 19 years. So, he's a very young man. He'd already married. He already had children. He married his half-sister, which of course was very common, gives us the heebie jeebies. But it wasn't that uncommon in Egypt. It saved the matrilineal and patrilineal line.

Now, being so famous and we're not really here to talk about Tutankhamun tonight in detail, but one thing that is of interest was what killed him.

He was a very young man. Why did he die so young? Many of his forefathers didn't die young. They were quite old. Ramses II was probably in his it's pretty old for those days. So, one of the speculations, of course, because we like everything to be sinister, was he murdered? And there's been a number of theories about this.

Now, what, what cause of death has been suggested for Tutankhamun. And one of the well, I'll give you a list of them. They're very interesting. Blunt force trauma. In the 1960s, they did an x-ray of his mummy and his skull, and a small piece of bone was discovered. You can see it there. And there was a lot of excitement. This must be because he'd been hit on the head. So clearly, you've been hit on the head. This must be murder. It's very easy to jump to that conclusion. Unfortunately, further examination proved that there was absolutely nothing to indicate that he'd been hit on the head. Blunt force trauma or anything else. The piece of bone had become dislodged either during the mummification process or when the mummy was being unwrapped. So that clearly had no evidence.

Metabolic conditions such as Klinefelter’s and Fröhlich’s were also suggested because he's the son of Akhenaten, Amenhotep IV, and he was the, The Heretic Pharaoh. And he, he brought in a new age of art and design, and he had his statues projected in a different way. And everybody looked at and thought, he must have some kind of disease. Therefore, if he's got it, his son must have it. So maybe it's a metabolic disorder. But genetic studies on Tutankhamun have proven to say that this is clearly not the case. He did not have any of these diseases. There's no real evidence for any of this, this is just speculation basically.

He had chest injuries. So, when they examined the mummy in latter times, there was this finding that there was injuries to the chest. That, too, has has been discounted when it's actually been looked at as a, as a proper scientific investigation.

Very small slides up here and I don't have my glasses on, and I can't remember what I wrote so apologies! Sickle cell anaemia. I did not touch that. One might suggest it's the curse of Tut is this know it was just technology and sorry they are really small. Oh! We're going back to the beginning. Okay. Where did we get up to. Sickle cell anaemia, Again, another speculative idea. No evidence to suggest it was true. Genetic studies have proven since that that's not the case.

A rogue hippopotamus. He's one of my favourite theories. Why he would attack a pharaoh, I have no idea? I think it was to do with the chest injuries. So, if you take away the chest injuries, then there's no evidence he was ever savaged by a rogue hippopotamus.

So, what does that leave us with? Well, there's a couple of things. We do actually have scientific evidence for, believe it or not, in about 165 different suggestions of why Tut died. Very few of them have any real empirical evidence.

One of them is some genetic studies that were done and the genes of a, of malaria, a Plasmodium were found. Perhaps not unsurprisingly, in Tut. And of course, we know malaria is a very dangerous disease. It can have quite dire consequences. It doesn't kill everybody. In fact, it has a relatively low mortality rate in reality. How do you get it? You get bitten by a mosquito. Where does Tut live? He lives in Thebes. He lives next to the Nile. What has the Nile got? It’s got mosquitoes. I reckon if you tested all the mummies in Egypt, 75% of them would have these genes. Because it was just widespread. I mean, everybody probably had it. Is it his cause of death? It could have been. There's no evidence that he died from this. As I say, it's not always a fatal disease and the second and third time that you have a bout of malaria, of course, it gets less and less. So there's no, yes there’s evidence he had had it. There's no evidence he died of it.

So, they did the X-rays in the 1960s and they found the bone chip. So, everybody got very excited and thought it was blunt force trauma and the butler had killed him or whatever the theory was. Fast forward to the mid 2000s and they did a CT scan of the body because technology has moved on. By this stage we're now able to 3D image these remains. So, we can virtually unwrap a mummy now. And mummies aren't really unwrapped anymore. The days when you used to unwrap mummies for entertainment, as was the case in the early 1900s and late 1800s are long since gone. And scientifically, we don't really need to do it. We just CT the bodies now. So, this was some of the early CT technology. And what did it tell us? Well, told us that he certainly hadn't been hit on the head, clearly confirmed that there were no other injuries. He had no other obvious disease processes going on. But one thing that they did discover was when they looked at the left knee and this is a little bit hard to see and apologies, it's the best CT image I could find of him. There was a piece of bone dislodged and a small fracture on what's called the medial aspect of the distal end of the femur. What am I talking about? The knobby end of your thigh bone that articulates on your shinbone, the inside part of it. And that was some conjecture around that. And it was clear there was clearly some sort of defect there on the leg. What did that really mean?

Well, then suddenly that spawned a whole new industry of of what killed Tut. He fell off his chariot. I believe the hippopotamus may have come back into it at some point. Why? He would bite him on the knee, I don't know. But anyway, there was all sorts of conjecture as to what would have caused this. And that's a a slice, if you like, of the CT scan. And you can see basically there there's a piece of bone that has been, so the knees turned around, a piece of bone has been dislodged. Very small, very small fracture line, very small piece of bone.

What can we interpret from that? Okay. A broken distal femur so, a broken thigh bone. Small dislodgment, no evidence that it's actually an open fracture because one of the conjectures was he's broken that part of his leg. He's got an infection. The infections raged on and he’s died as a result of septicaemia or a blood borne infection. There's no evidence to say it was an open fracture. So, what I'm talking about is when the skin is broken apart like a compound fracture, or it's so bacteria can get into the system. No evidence that there is no evidence that there isn't, because this is a mummified body. The, the soft tissue is very compromised by this stage. So, we're trying to draw modern conclusions from compromised ancient tissue. It's always going to be a bit of guesswork.

The other possibility was what's called FES or fat embolism syndrome. Now, when you break a bone, particularly a femur, there's fat in the bone, in the marrow and in the end of the bone, and that fat leaks out into the system. And if it can get far enough, it can cause problems, it can cause heart attacks and it can cause brain haemorrhages. Is it possible? Well, it doesn't happen very often. We know that from our clinical studies, but it's a possibility. But it's a very small fracture, very small dislodgment.

So, I guess, what do I think happened? Well, working in the area of forensic, I'm very cautious about interpretation of things. So, I have to absolutely be convinced that something's suspicious before I'll believe it. What I think is the possibility, and it's only another bit of conjecture, is in the early 20th century when the mummy was found, they unwrapped it and they unwrapped it because it was covered in thick resin. It was stuck to the coffin. It was stuck to the death mask. They had to use hot knives to try and cut it out. So, to get his body out and unwrapped, because they're looking at this point for amulets and things like that, they have to break him into pieces. So, the arms are broken off, the head is broken off, the hips are broken off and the knees are broken off. So, my conjecture would be, I suspect some of the damage that we're looking at is probably postmortem damage that happened at the time of the original unwrapping, which is not very exciting but there you go. Certainly not as exciting as a rogue hippopotamus.

So that tells us something about cause of death, potential disease, possibilities for the royals in in ancient Egypt. But what did the Egyptians actually know in a general sense? I mean, they were our conjectures. But what did the Egyptians know about health and disease? And they knew quite a few things. They knew a lot about the fundamentals of, of what was going on. They understood about hearts, which is why they preserved them so carefully. They misunderstood much of, of what that was. They felt that the heart was the seat of everything. They didn't quite understand it was the brain that was doing a lot of the thinking work. I guess because you feel emotion through your heart. You can physically feel it, you know. You can't feel yourself thinking. So maybe that's why they became so focused on it. They didn’t understand physiology. They knew anatomy because they were good anatomists. They were cutting people up all the time in removing their organs. I mean, they were, they could come and work in our state mortuary. They knew as much about anatomy and where things went, they just didn't know exactly what they did.

They knew they had to save them. They knew they were important, but they didn't understand physiology or biochemistry or any of those things They thought the heart pumped all the fluids of the blood, of the body. I mean, all fluid, semen, everything was urine was all pumped around by the heart. So, you know, they had a half a knowledge, but they did know quite a lot and they treated people. These are some of the papyri that have been found and they are some of the things that they talked about and, and how they would treat them. So, they understand some disease processes, they understand injuries. They don't understand all the mechanisms and as I say, the physiology or anything behind them. They don’t understand like the microscopic causes of disease. We don't know that for thousands of years until afterwards. But they did have all these wonderful papyri, as I say, and they had quite detailed things about what to do if these things happened to you.

They also relied a lot on magic. They relied a lot on the gods protecting them. So, you had a series of gods – Sekhmet, Bes, Tawaret. All sorts of things from just, please protect us to specifics like childbirth and female diseases and all of those kind of things. They would have very specific amulets for those and so they practiced medicine with magic at the same time. And this is just a list of the type of things that we know from our studies in more recent times that the Egyptians would have suffered from. And I'm going to show you some examples of that from my work when I've been in Egypt. So, it's a very long list. You get the idea. There's all sorts of things. Many of them, of course, all the things that we still suffer from today.

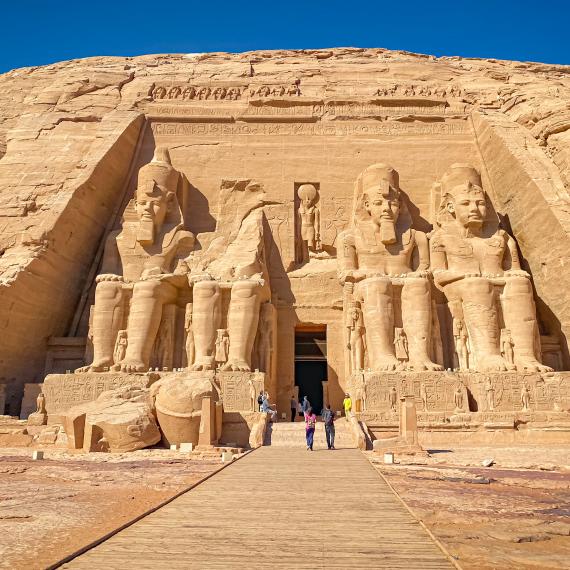

So, this is where I work part of the time at Thebes, which is now called Luxor in modern times. And some of you here probably have visited Thebes, Luxor. Very important place. It's where the valley is, the Valley of the Kings. So many of the great monuments. It's the capital of the New Kingdom. So, this is the timeframe of Tut and Ramses and all of those famous pharaohs. So, it's a very important place in Egypt. That's the mountain that I work on. It's known as Dra Abu’l Naga. It's on the West Bank of the Nile. So, I'm taking the photo from the East Bank and looking across. It's where the tombs of the nobles are. It’s situated between Hatshepsut's, Deir Al Bhari and the Valley of the Kings is on the other side of it. And this is where people who weren't royal but who were very important were buried.

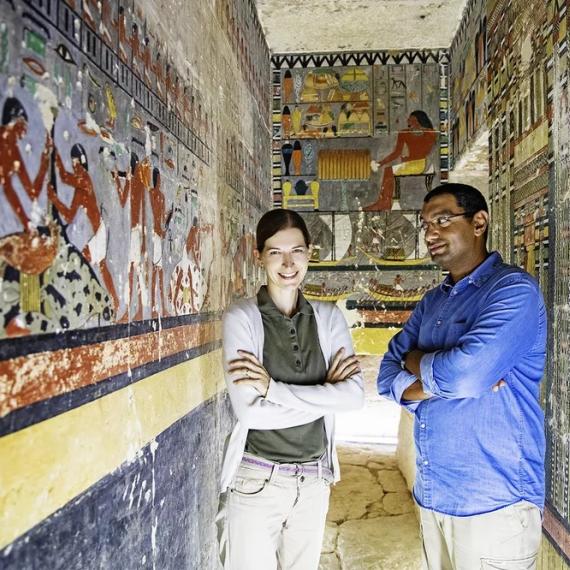

These are some of the tombs that I've excavated. TT just stands for Theban Tomb. Most of them, all of them New Kingdom Tombs. Various people – Neferrenpet, Amenemope, Shuroy. They were all important people. They were noble, but they weren't royal, but they played important part in the royal dynasties.

And there's me and one of my helpers. He was known as the Count. His name was Achmed, and he could count to a hundred and that’s how got the job. And Achmed could count anything to a hundred. You just once you started him, you couldn't stop him. He'd go all the way through to a hundred. Anyway, he was very good. He used to help me sort the bones. He was, he was a lovely little guy.

And one of the other places I worked was up north. It was closer to Cairo. Saqqara, which is just outside. And I was working at the Teti Cemetery. We were excavating the, the cemetery which is attached to the Teti Pyramid. Now Teti’s Old Kingdom so, we're going back even further, we’re back to 5000 years at this point. But the cemetery or the necropolis, which is in front of it, which is that village of the dead that you can see, they basically were tombs. Important, noble people were buried there and then as the years went on and they moved away from this area as being as important, Memphis, which was one of the capitals at the time, it got used more and more by the average people and they all wanted to be part of this sacred space. So, they came and buried a lot of locals there, A lot of ordinary folk really. Didn't have to be that special. But you could get a good a guernsey at the Teti cemetery, so to speak.

And a lot of shaft tombs. Very dusty, very small. And for a person who has a fear of heights and claustrophobia, this was one of my bravest expeditions. They lowered me down in a basket and I closed my eyes all the way down. And it was a great amusement to the workmen to see me so scared. Not so amusing for me. Anyway, I got to the bottom. Nothing tragic happened. And there was all these wonderful human remains. All been robbed out. Everything is robbed out. Nothing is pristine. They've all been picked over many times, sadly.

So, you can see here there are a lot of spinal fractures. So, this is looking at the bones of the spine, the vertebrae. You can see what a normal one looks like there in the X-ray and how there's been a collapse in what we call the anterior end. So, all the spongy bone inside has started to lose its integrity. It's like osteoporosis that we all suffer from, that people suffer from today and the end part starts to collapse. And that causes all sorts of catastrophes. The bone starts to remodel, bits of bone start to grow out and places they're not meant to. And it can be very painful and then you can get spinal fractures as a result. Unfortunately.

That's a big, long word. We shorten it to DISH. It's diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis. What does that really mean? Well, basically, on your spine, you have two big ligaments that run down the front and the back, because you don't want your spine going floppy, because that would be very bad for everybody. So, we have to keep it in a nice alignment, but it has to be flexible. So, we have these two big ligaments, they're very flexible. But what happens when they calcify and become bone. Not so good and in certain conditions, because people have certain pathological problems, genetic predisposition to it, the bone, the ligaments will actually calcify, and your spine starts to look like someone's dripped candle wax down it and all of the individual little elements start to stick together. So, you'd have a very, very stiff and sore back. And surprisingly, there was quite a few examples of it.

Herniated spinal discs. So, anybody who's ever had what's called a slipped disc, our discs don't slip. A disc is made up of the little space in between where the spinal bone's fit together. And that disc consists of an annular ring called the annulus fibrosis and a piece of a jelly like substance called the nucleus pulposus. Don't, I won't question you on this afterwards. You don't have to remember these names. But what it does, that's what the disc is. And when that that annular ring for whatever reason - overwork or you strain it too much, starts to rupture, then the pulpy stuff comes out. And when the pulpy stuff comes out, you have a slipped disk and that's where you get pain and inconvenience. And what it leaves sometimes are these funny little divots all along.

So this person is quite a young person, but they've had quite a lot of back problems because these little things are called Schmorl’s nodes. After Mr. Schmorl who discovered them and named them. And basically, they're an indicator that there's been back problems for this person. So, you get a lot of that in Egypt, spinal degeneration. So, remember I said when those little discs and you see the remnants of it, that that brownish substance, now these bones are a thousand years old - so Egypt's very good at preserving things. Basically, little bony spicules start growing up because what it wants to do is stop the, the spine bones moving around because they're damaged. So, to stop them moving around and causing more trouble, it grows bone up and it grows bone down and they fuse. So, you get a fused element. And again, this is as a result of spinal damage, overwork, it can be some kind of pathological disease; all sorts of things cause this. Mostly in Egypt I think it was part of the aging process. The bones were very light and demineralized, so there probably was a lot of osteoporosis as well because the diets weren't all that great.

And osteoporosis, what happens, the internal bone starts to break down, you lose that, you have horizontal and vertical struts. The little horizontal struts go away. The vertical struts are left. They're not very good at managing the spinal forces that are going down your spine. And so you start to get vertebrae collapsing and hence you get all those other problems. And this was fairly widespread.

Arthritis. A lot of them had arthritis. You can see this one to your left is a kneecap, a patella. And if you flip it over, that's the front side. And in the circle, those little holes, they're not meant to be there. That means that the cartilage that sits between that and your knee because you're bending it all the time, has gone and you've now got arthritis and you get down sometimes to bone wearing on bone and you can see the shiny surface where the all the cartilage is gone. You've got bone rubbing on bone, which would have been very painful, and you've got a lot of inflammation, the same as the, the spinal bone. After that. That's one of the bones, lower bones of the neck that's got this degenerative change and the elbow on the end. So, a lot of the joints they got all of this where and then you got inflammation and then you would get this bony growth, so this is again probably hard work and old age.

Periostisis. What is that? The bone is covered in a like it's almost like a plastic covering over the actual bone itself. It has all sorts of roles that it must play. But when that gets injured, so you hit it or you kick it or you do too much like kids when they're very young, they might get shin splints. We talk about it as shin splints. That's when the periosteum gets damaged, and an inflammation response happens, and you get extra bone. Now it's very hard to see, but along that, inside with the arrows pointing, this extra bone inflammatory bone has then deposited. So, this person is probably just overused their legs. A lot of hard work, a lot of a lot of lifting, a lot of walking in sand. Believe me, when I'm in Egypt, there's a lot of sand and it's quite hard work walking up those mountains. I can tell you! The bone on your far right, of course, is an elbow. And so that's got a lot of periostotic change as a result of overuse and damage.

Bony, benign lesions. This is the inside of a piece of your cranium turned over. So you take it off and you're looking at the inside. It's called a button osteoma. It's just a little bony growth that occurs. Doesn't usually cause any problems. It's not malignant or metastatic in any way, but there was quite a few of those appeared.

Dental problems. Obviously, dentistry was not big in Egypt 3000 years ago because they're living on sandy diet. You're eating sand. Everything in Egypt is sand. I mean, you're living in this Sahara Desert. It’s hard to avoid, but the sand everywhere. So, you're always, your food is covered in sand. So, as a consequence, all the enamel on your teeth starts to wear away. It opens up the pulp chamber. Bacteria get in and it causes eventually tooth loss. So, there's lots of decay, lots of what we call dental attrition and lots of tooth loss. So, the one on the far right there, of course, no teeth at all. That's the lower jaw. So, no teeth at all and been gone for a long time. So, they’re just chewing on their gums.

These were particularly nasty abscesses; they're called periapical abscesses. What happens is that process, the enamel wears the way the infection gets in everybody's had a sore tooth or some decay or a toothache. You know how much it hurts? Well, they don't get to go to the dentist, and they don't get antibiotics. So, what does it do? It gets down into the bone and it starts to eat the bone away around where the tooth is. And if you can see those areas - sort of arcs and you can see with the bones missing on the tooth, they are particularly nasty dental abscesses, quite dangerous untreated, There's a nasty one, two nasty ones, actually. The one on your left is probably what we would call a reactive one. So that's he's had that at that time when he's died. There's very little remodelling and there's lots of evidence that there was a raging infection going on. Now, untreated, this can cause infections obviously in the head is very dangerous and you can die as a result of it. And I suspect quite a lot of Egyptians because of these types of conditions, this was one of the causes of death.

They had some strange anomalies, particularly in Saqqara, where I think there was a lot of inbreeding, dare I say. So, teeth aren't supposed to grow out of the side of your upper palate. I mean, we still have that today. You do get these anomalies, but it's not normal. And if you look at the mandible, so we're looking down long ways into your lower jaw and you might be able to see there's just these teeth, extra teeth have appeared in there. They're never going to erupt. They're just sitting in the mandible. So, again, this is a genetic abnormality. Probably as a result that they're living in small villages and everybody's getting married and unfortunately marrying their sisters a lot of the time. So, a lot of genetic abnormalities.

This is Saqqara, the late period. So that's the Teti Cemetery I was telling you about, this is a late period coffin. So, this is coming more up to Graeco-Roman times. We've come forward quite a long way in time. The cemetery is being reused by the average people and some fairly elaborate coffins. This is a ceramic coffin with a gentleman found inside. Basically, old age. I mean, you can see where his, he had one tooth left. I always felt sorry for him. He's used it a lot, though. All the rest of his teeth have gone, and he's had a couple of teeth and they've just worn away the top of his jaw. He’s just chewed on it till he's chewing on his gum and then he's wearing away the bone in his gums as well. He had arthritis in his knees, he'd had a broken hand and he had spinal degeneration. He was probably about 45. Who knows. I'm guessing. Maybe not, I'm hoping not! I did feel, I did feel my age occasionally when I was over there and thought yeah, I know how you feel, mate. That's not nice.

He also had a nasty fracture of the femur. So, this is his right femur, his right thigh bone. I think he had osteoporosis. We get this today. A lot of people who have falls are as a result of something like this happening in the elderly. So, the bone gives way and then the person falls. It's not usually you fall and break your femur, the femur breaks, and you fall is usually the process. We get a lot of this today, unfortunately, no surgical intervention. He ends up with an infection. You get a lot of bony disposition and bony scar growing around it because it's trying to stop the joint moving and he ends up with a malalignment. So, he's got hip problems as well. I mean, he's not in a good way: back, knee hip, no teeth. It's not a good life. But he has a very nice coffin, so.

I was never sure with this one, whether it was TB or cancer, it could have been metastatic. I'm leaning towards metastatic and basically these are the bones of the spine. They haven't worn away as a result of erosion and being in the sand. They've worn away inside the body and they've all remodelled. So, he's lost all of the height of his vertebral bodies, so his whole spine would have collapsed. I can't imagine how painful this must have been in a living person. He's not very old, so he doesn't survive very long. So, I am wondering if it is a metastatic cancer rather than TB. There was TB in Egypt, but it was much later on. But that can happen with TB untreated.

He's got a particularly nasty abscess. That is a periapical abscess that is raging when he dies. Now is it cancer or is an abscess? Again, it's very difficult to tell. It could be one or the other. But again, probably I would hazard a guess and say fairly surely this is probably the cause of death for this gentleman.

He's just he's, he's been in a nasty accident. He's from Saqqara. He's been hit in the face with something. He's broken his spine and he's broken one of his lower arm bones as well. As a consequence, he's also got some arthritis in his knee, but I suspect almost everybody had arthritis in their knee at some point. As you can see, he's got nothing at the top. His teeth are gone, he’s worn away where it's been broken. And he's got a nice little pyramid really for his teeth on the bottom there.

So how are they distributed these diseases? Well, basically, the majority of the diseases that we see are in the spine. Unsurprisingly, pretty common as to what we get today. That's, that's not too different from a modern population. More distributed we get sometimes in the head, the shoulders obviously the joints are very affected. We get a lot of joints that are affected.

Can't tell anything very much about soft tissue pathology because there's not a lot of soft tissue left. Most of these bodies have been picked over. They were never well mummified in the first place. They've been robbed out in the tombs. So, you get some pretty tatty remains. It's very hard to tell.

That's pretty much the areas. And they're the types of things that the ancient Egyptians, including the pharaohs, they didn't escape as well. Ramses II must have had some very bad toothache because he had very worn teeth and he had abscesses. Bad backs. And I think everybody can relate to that after a certain age. They had a lot, it was a lot of hard work, arthritic knees, broken bones, cancer and infections, all the types of things that a modern population would have. Unfortunately for them, there just wasn't a, a hospital or a doctor or antibiotics or anything else that they could then get to relieve. Though they did obviously have their magic and their medicine as well. So, they had some some relief, hopefully.

And just to end on something that we've not as unpleasant, not everything in Egypt is about death and disease. It's not all I did. This is a picture I took standing on the front of one of the tombs in Luxor. And it's a very smoky morning because there's a lot of smoke in Egypt all the time there was burning things. This is one of our workmen who's working in front of me. And it was just a beautiful, crisp morning on the front of the mountain with the tourists who would float by and sometimes I would come out of the tomb and there'd just be this group of tourists waving at me from a balloon. You'd be going, hello and then you’d wait, and we'd have bets to see which balloon was going to collapse into the farmer's field below. And that was something we’d do to amuse ourselves. I don't think the tour, nobody died. Nobody died. Okay. We didn't do it because people were dying. It was just it would slowly deflate. We'd pick which one, much to everyone's amusement but the tourists. So, that brings us to the end.

(applause)

Okay, I think we've got quite a bit of time for questions. Anybody have any questions?

Event MC: Perfect. We can probably have, yeah, one or two questions.

Audience member: Hello. From your experience across all the thousands of years, all the dynasties, are there patterns in people's health? Did it change? Was there a good time to be an ancient Egyptian?

AB: No (laughs) No, there was, there was no good time to be an ancient Egyptian. Look, I think as as as time went on and they had more exposure to Roman times and things like that, things probably got a bit better for them in terms of treatment. But basically, the things that you saw there, that was the lot of the ancient Egyptian, probably from pre-dynastic all the way through to Romano, Roman times, Roman Greco-Roman times. So yeah, it wasn't it wasn't a great place to get sick.

Audience member 2: Sorry. How did they help manage these diseases? Did they have doctors that helped with symptoms and such.

AB: Yeah. Yeah, they did. They had people who were were trained from, from the papyri that you saw, the medical texts. So, they knew about that and they would apply some rudimentary kind of things. A lot of it was magic. As you can see. They'd be given amulets. Take an amulet, go home and lie down. I think in some instances might have been the treatment. But no, they, you know, that's underselling them a bit. They they did have treatments. And some of them probably were quite effective. Some of the natural treatments for toothache and things. Obviously, the more difficult ones. They knew to splint bones, but of course they couldn't stop osteomyelitis and, anything to do with an infection. But yeah.

Event MC: Perfect, I think it was time for one more. If there's any further questions,

Audience member 3: What's the highest burden of Guinea worm that you've seen in a corpse?

AB: I haven't ever seen guinea worm in a corpse because you would only detect it under a microscope. And when I'm working there, I don't have you know, it's non-invasive. You'd have to actually have access to the technology to be able to section it and have a look. And unfortunately, I, when, you're not allowed to take anything away from the tomb unless it's under special dispensation. You can go to the University of Cairo. But generally, no, I wouldn't have access to that. So I yeah, I'm not sure. Probably quite high in some areas.

Event MC: Wonderful well, that is the end. So please pop your hands together and say thank you.

(applause)

More Episodes

John Mirosevich explores the varied history of Thonis-Heracleion, Egypt’s greatest Mediterranean port for 400 years.

Listen to Hon Dr Anne Aly MP who joined us at Afterlife Bar for a presentation on the Discoveries of Ancient Egypt exhibition.

Join committee members of The Ancient Egypt Society of WA Inc for a unique opportunity to dig deeper into Egyptology.

Dean Kubank revisits the Temples of Nubia and the enchanting Temple of Isis at Philae.

Celestial Timekeeping in Ancient Egypt - Discover how Ancient Egyptians used the heliacal rising and setting of stars to construct their star clocks and civil calendar.

Discover the story of the pharaoh Djedkare, his family and courtiers, and take advantage of the rare opportunity to hear from visiting international Egyptologist Dr. Mohamed Megahed of Charles University, Prague.

Discover the story of the pharaoh Djedkare, his family and courtiers, and take advantage of the rare opportunity to hear from visiting international Egyptologist Dr. Hana Vymazalová of Charles University, Prague.

Discover Egypt’s ancient legends of creation, death and resurrection. Tales of Ra, Osiris, Isis and Horus will unlock the meanings of the art, religion and funerary practices of ancient Egypt.

The Dynasty 6 Vizier named Weni the Elder, who lived about four and a half thousand years ago, had a detailed biography written on the outside of his tomb.

How, when and why was mummification invented? The answers may surprise you.

Ancient Egyptian Astronomy Unraveled - Discover how the Ancient Egyptians used their knowledge of the sky to design and position their temples, statues, and roads.

As part of our evening Afterlife Bar series at WA Museum Boola Bardip, we welcome a series of speakers to dive deeper into Egypt. Join us this week as we hear from Dean Kubank on Temples and Tombs.

Renowned expert in ancient Egyptian history Daniel Soliman delivered a fascinating talk, as we celebrated the launch of the WA Museum Boola Bardip's Discovering Ancient Egypt exhibition.