Images of the Moon in Fairy Tales around the World

Writer, puppeteer, and folklorist Clare Testoni tells the story of the Moon's many faces in folk and fairy tales around the world.

Explore the stories of Moon Princesses from Japan, fox moon maidens from Russia, and The Man in The Moon from England, alongside other snippets of fables and tales of lunacy and love.

-

Episode transcript

[Recording] You're listening to the Western Australian Museum Boola Bardip Talks Archive. The WA Museum Boola Bardip hosts a series of thought-provoking talks and conversations tackling big issues, questions and ideas. The Talks Archive is recorded on Whadjuk Nyoongar Boodja. The Western Australian Museum acknowledges and respects the traditional owners of their ancestral lands, waters and skies.

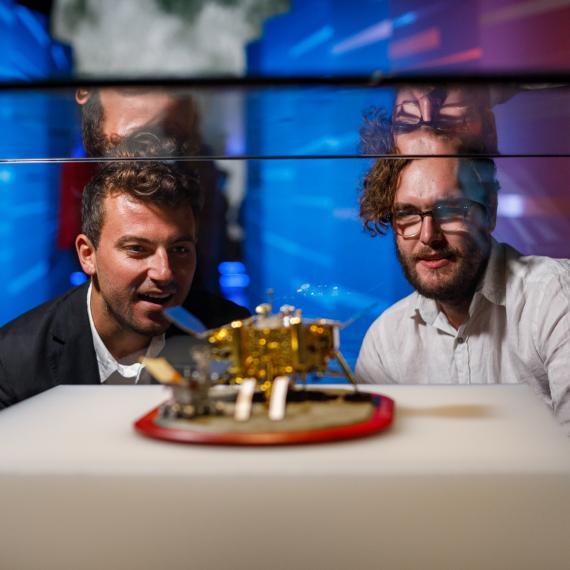

Facilitator: Good evening everybody. Welcome to the WA Museum Boola Bardip ‘To the Moon’ exhibition and this final Lunar Lounge event we have here tonight. So we have a few things going on this evening. We have a talk up first here and then, later on tonight, just inside the gallery, we have a band performing from 7:30.

So please stick around and enjoy all of these things. But before we get started tonight, I’d just like to take a moment to acknowledge the lands on which we are gathered on and learning here tonight, the lands of the Whadjuk people of the Nyoongar nation. May we pay our respects to elders, past and present, and extend those respects to any First Nations folks here with us tonight.

So up first, we have our guest speaker this evening. This is Clare Testoni, who will be taking you through the moon as it's known in folklore and storytelling. Please make them feel welcome.

[Audience applause]

Clare Testoni: Hi. I wanted to second that acknowledgment of country and acknowledge the Nyoongar people as the first storytellers on this land as well, since we're talking about stories. I'm not going to be talking about Nyoongar stories tonight as it's not my place and not my area of research, but I want to acknowledge that they have their own beautiful stories about the moon.

So I'm Clare, and I'm a playwright and a puppeteer and a folklorist. And tonight I'm talking about the moon in fairy tales and folk tales around the world. Although I'm mostly focusing on my area of strong knowledge, which is Europe and Asia.

So the moon has always been a figure in our stories. Like other large forces of nature, like the earth, the sky, the water, the sun, the moon’s celestial companion. In many ways, the moon was the most mysterious of these figures in our early stories. It came out at night. It was light, but gave no warmth. It changed its form, and it dictated our earliest calendars. In many creation myths about the moon, the sun and the moon are coded female and male, respectively. And in these myths, one chases the other across the sky. Either the moon chases her lost love, the sun, or as is in West Africa or the Philippines, the moon runs away from her hot-tempered husband, trying to hide and change her shape.

Over time, in many of our cultures, these stories became more complex, told and retold. The figures of the moon, the sun, the wind became more human. Stories became longer and more literary. And I'm not going to be talking much about creation myths. [indicates to presentation slides] This is an illustration from the Aztec one, where the rabbit gets thrown up into the moon, popular all around the world. But tonight we're going to be talking about folk and fairy tales.

‘Fairy tale’ is always a very cumbersome name, since they rarely have fairies in them unless they’re French. ‘Wonder tales’ is the name I preferred, which is a translation of the Russian and whatever you call them, they’ve existed predominantly as oral artforms for the last thousand years across all cultures. They're short, standalone, non-religious tales in which something strange and magical happens, such as pumpkins turning into coaches, fishbones granting wishes, or boys climbing giant beanstalks.

In English and French, the moon sometimes take on that giant like appearance. It's only in England, in France or Brittany, let's be specific, that the moon is male and like Jack's giant in stories like ‘The Snuffbox’ collected by Paul Sébillot. [indicates to presentation slides] There we go. From Brittany, the late 19th century. In this tale, the hero is searching for his lost magical snuffbox that grants him wishes, very relatable content, and his journey takes him first to visit the moon, then the sun, and finally the winds.

This is an excerpt from the tale in English:

[CT begins the reading]

Someone told him he ought to consult the moon, for the moon travelled far and might be able to tell him something. So he went away, away, away, and ended somehow or other by reaching the land of the moon. There he found a little old woman who said to him, ‘what are you doing here? My son eats all living things he sees and if you were wise, you will go away without coming any further.’

But the young man told her his sad tale, and how he possessed a wonderful snuffbox, and how it had been stolen from him. And now he had nothing left. Now he was parted from his wife, and was in need of everything. And he said that perhaps her son, who travelled so far, might have seen a palace with layers of gold, tiles of diamonds, and furnished all in silver and gold.

Now, as he spoke these last words, the moon came in, and he said he smelt mortal flesh and blood. But his mother told him that it was an unhappy man who had lost everything and he’d come all this way to consult him, and bade the young man to not be afraid but to come forward and show himself. So he went boldly to the moon and asked if, by any accident, he had seen a palace with layers of gold and tiles of diamond, and all the furniture silver and gold. Once this house belonged to him, but now it was stolen, and the moon said no, but that the sun travelled farther than he did and the young man had better go ask him.

[CT ends the reading]

The idea of visiting the sun, the moon, Et cetera, Northern Lights, East Wind, West Wind, is very common in fairy tales from the north. While the moon isn't always personified, it’s traditional that the hero be searching for something beyond the known world. In one of my favourite tales, the Norwegian ‘East of the Sun, West of the Moon’. As the story suggests, a young girl has to travel to that mystical point beyond the sun, beyond the moon, and she gets there carried by first the East Wind, West Wind, South, and finally North Wind. Things normally happen in threes or fours in fairy tales, depending what country you're in.

The Sami, the nomadic First Nations people of far north Scandinavia, have the story of the daughter of the moon, in which the beautiful daughter of the moon is pursued romantically by the cruel and hot to the touch son of the sun. She is promised to marry one of the Northern Lights, who are four brothers, and she does not like the rough, violent sun child. To protect her, her mother sends the moon daughter to Earth as a baby to be protected by an old farming couple, a trope I'm going to revisit later. But what I find interesting in these representations of the moon versus the sun, is the moon is often passive, beautiful. She is ornamental, a respite from the hot necessity of the sun. Under the moon is the witching hours, the moment of transformation into a true self. The swan princess in the moonlight is once again a girl, and the rusalka, or the ghost of the forest, is revealed to be dead and ugly.

Now, we have to talk about the Grimm Brothers story ‘The Moon’. It's not their most famous. It's not their best. But they are the Brothers Grimm. They’re big words in the world of fairy tales. Their moon story faces, brings the moon forward as a technological advancement that several brothers steal from another country to horde as their own. A pressing narrative for the early 19th century when they were collecting their tales. I don't have an illustration, so enjoy this nice one of something else.

Here's an excerpt from The Brothers Grimm in English, not German:

[CT begins the reading]

In days gone by, there was a land where the nights were always dark and the sky spread over it like a black cloth. The moon never rose and no star shone in the obscurity. At the creation of the world, the light at night had been sufficient. Three fellows went out of this country on a traveling expedition, and arrived in another kingdom, where in the evening, when the sun had disappeared behind the mountains, a shining glow was placed on an oak tree, where she shed soft light far and wide. By means of this everything could be well seen and distinguished, even though it was not so brilliant as the sun. The travellers stopped and asked a countryman who was driving past with his cart what kind of light that was.

‘That's the moon’, he answered. ‘Our mayor bought it for three thalers and fastened it to the oak tree. He has to put oil in it daily and keep it clean so it may always burn clearly. He receives a thaler a week for all of us for doing so.’

When the countrymen had driven away, one of the travellers said, ‘We can make some use of this lamp. We have an oak tree at home just as big as this, and we could hang it on that. And what a pleasure it would be to not have to feel about the darkness at night.’

‘I'll tell you what we do,’ said the second. ‘We'll fetch a cart and horses and carry away the moon. The people may buy themselves another.’

‘I’m a good climber,’ said the third, ‘and I will bring it down.’

They brought a cart and horses, and they climbed the tree, bored a hole in the moon, and passed a rope through it, and let it down.

When the shining ball lay in the cart, they covered it with a cloth so that no one may observe theft. They covered it, conveyed it safely to their own country, and placed it on a high oak. Old and young rejoiced in the new lamp that let its light shone over the whole land, and bedrooms and sitting rooms was filled with it.

The elves came forth from their caves and rocks, and tiny little elves in their red coats danced in rings on the shadows.

[CT ends the reading]

The moon ends up escaping like a balloon into the sky, and they have to share it with everyone. And the travellers look like right idiots for charging everyone for use of the moon.

Stories like this one and similar are possibly the origin of the idiom, ‘no one owns the moon.’ Like many of the tales collected by the Brothers Grimm, this tale holds something very old and also something new for its era. There is an element of the creation myth, of how the moon came to be. But in 1812, when it was first published, there was also, there was also an expectation that fairy tales contain a moral: don't steal other people's culture. And this was important to Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm when they recorded the German tales under French occupation.

‘Moral’ in fairy tales is a particularly modern invention by the French. Perrault, Charles Perrault, best known for the glass slipper version of Cinderella, Little Red Riding Hood, Puss in Boots, all the hits. He wrote morals at the end of each story, partly to get it past censors, as a lot of the fairy tales were coded stories about people at court, but that's another story. Back to the moon. But you will find in older stories and stories collected before the fashions of publishing fairy tales, they’re often without moral message, sometimes without a happily ever after, but with more a sense of resolution. They’re happy to just be beautiful and meditative.

An older version of a lost moon story comes to us from Lincolnshire in England, when the moon comes down to Earth as a woman and is trapped in a bog after helping guide a man out with her light. The story that’s reminiscent of Neil Gaiman’s fallen star in the book and film Stardust, but a bit less romantic. I’m not going to do the accent, by the way. I tried it and it’s just not going to work. This is written in Lincolnshire dialect.

[CT begins the reading]

And there lay the moon, dead and buried in the bog, till someone set her loose and who'd know where to look for her. Well, the days passed and ’twas a time when the new moons come in and the folk put pennies in their pockets and straws in their caps to be ready for her and looked about, for the moon was a good friend of the marsh folk, and they were main glad when the dark time was gone, and the paths were safe again. Evil things were driven back by the blessed light into the darkness and waterholes.

But days and days passed. And the new moon never come. And the night were aye dark and evil things were worse than ever. And still the days went on and the new moon never came. Naturally, the poor folk were strangely feared and mazed, and a lot of them went to the wise woman who dwelt in the old mill, and asked if she could find where the moon was gone.

‘Well,’ she said, and she looked into the brew pot and in the mirror and in the book. ‘It be main queer but I can’t rightly tell you what happened to her. Hear ought, come and tell me.’

So they went on their ways, and as days went by, never a moon come. Naturally, they talked. My word, did they talk! Their tongues wagged at home, and in the inn and in the garth. But so came one day, as they sat in the great settle in the inn, and a man from the far end of the boglands was smoking and listening when all at once he gets up and slapped his knee.

‘My faicks!’ He said. ‘I clean forgot, but I reckon I kens knows where the moon might be.’

And then he told them how he was lost in the bogs, and how, when it was nigh dead with fright, light shone out, and he found the path, and found home.

So off they went to the wise woman and told her about it. And she looked long into the pot and the book again, and then she nodded her head.

‘It’s dark still, chill the dark, and I can’t rightly see. But I do tell ye, and I'll tell ye to find out yourselves. All of you, just afore the night gathers, put a stone in your mouth, and take a hazel-twig in your hands, and say never a word till you're safe home again. Then walk on and fear not, for in the midst of the marsh you find a coffin, a candle, and a cross. And then you be not far from your moon; look m’appen and you’ll find her.’

So came the next night in the Darklings, and they all went out together. Every man with a stone in his mouth and hazel twig in his hand, feeling, and thou must reckon feared and creepy. And they stumbled and stottered along the path in the midst of the bogs. They saw nought, though they heard sighings and flutterings in their ears. And they felt the wet, cold fingers touching them. But all at once, looking for a coffin, a candle and a cross, when they came nigh to a pool beside a great snag where the moon lay buried. And all at once when they stopped, quaking, mazed and skeery, there was a great stone, half in half out of the water. And for all the world like a strange big coffin, and at the head was the black snag snatching out its two arms in a dark, gruesome cross. And on its tiddly light flickered like a dying candle. And they all knelt down in the mud and said, ‘oh, Lord, first forward because of the cross, then backwards to keep off the bogles,’ but without speaking it out, for they knew evil things would catch them if they didn’t do as the wise woman told them.

Then they went nigher and took hold of the big stone and shoved it up. And afterwards, they said for one tiddy minute, they saw a strange and beautiful face looking up at them, glad-like out of the water. But the light came so quick, so white and shining, that they stepped back, mazed by it. And the very next minute, when they could see something, there was full moon in the sky, bright and beautiful, clear as day, stealing into the very corners as though she’d driven the darkness and the bogles clean away if she could.

[CT ends the reading]

I always like that. We don't say the word mazed any more, do we? But let’s get out of Europe. I really need to talk about the most famous moon fairy tale, which comes from Japan. Japan, interestingly, has a history of literary fairy tales that's quite similar to what evolved in France during the court of Louis the 14th, when Charles Perrault was writing his tales, or the earlier fairy tale collection by Arabic scholars in the 12th and 13th centuries, some of which we now know as the collection collected by a Frenchman, though, so, as the Arabian Nights or the Thousand and One Nights.

Although the Japanese tale of Kaguya-hime, or Princess Moonbeam, is probably older still, moon viewing parties were held back by the Emperor as far back as 906 AD in Japan. The tale is considered the oldest surviving monogatari, a short traditional work of fiction, and the oldest manuscript we have dates back from 1590.

In English, it's sometimes known as the ‘Tale of the Bamboo Cutter’, and it strangely has some similarities to the Sami tale I discussed earlier, although how, who knows? The story tells of an old bamboo cutter who one day discovers a tiny shining baby in the bamboo and brings her home to his wife to raise as their own daughter. And by tiny, I mean inches. She glows like moonlight, so they call her Kaguya-hime, or Princess Moonbeam. Soon, when he goes to harvest bamboo, the old cutter finds gold inside the bamboo and is able to care for his daughter in the style that her mystic beauty requires.

All these things go as they do in fairy tales, and she grows up beautiful and perfect, and is soon courted by four Samurai, for whom she sets four impossible tasks to win her hand, which they all fail and cheat and do not accomplish. Soon the Emperor himself tries to woo her, but she rejects even the Emperor.

It finally comes to light, pardon the pun, that she does not belong to Earth at all, but to the moon. And here I'll read a little extract from the condensed version by Yei Theodora Ozaki, a Japanese woman who, in 1903, collected a version of this tale for English speaking children.

[CT begins the reading]

At this time, her foster parents noticed that night after night, the princess would sit on her balcony and gaze for hours at the moon in the spirit of deepest dejection, ending always in bursts of tears. One night, the old man found her thus weeping, as if her heart were broken, and he besought her to tell him the reason for her sorrow.

With many tears she told him that he’d guessed rightly when he’d supposed her not to belong of this world, that she had in truth comes from the moon, and that her time on earth would soon be over. On the 15th day of that month of August, her friends from the moon would come fetch her, and she would have to return. Her parents were both there but having spent a lifetime on the earth, she had forgotten them, and also the moon world to which she belonged.

It made her weep, she said, to think of leaving her kind foster parents and the home where she had been happy for so long. When her attendants heard this, they were very sad. They could not eat or drink for sadness at the thought that the princess was so soon to leave them.

The Emperor, as soon as the news was carried to him, sent messengers to the house to find out if the report was true or not. The old bamboo cutter went out to meet the imperial messengers and the last few days of sorrow was held upon the men. He had aged greatly, and he looked much more than his 70 years.

Weeping bitterly, he told them that the report was only too true, but he intended, however, to make prisoners of the envoys from the moon, and do all he could to prevent the princess from being carried back there.

The old man gave orders that no one was to sleep that night, and in the house they were all to keep strict watch, and must be ready to protect the princess. With these precautions and the help of the Emperor’s men at arms, he hoped to withstand the moon messengers. But when the princess told him that all these measures would be useless and that when her people came for her, nothing could prevent them from carrying out their purpose. Even the Emperor’s men would be powerless. And she added with tears that she was very, very sorry to leave him and his wife, whom she had learned to love as her parents, that if she could do as she liked, she would stay with them in their old age and try and make some return for all the love and kindness they had showered upon her during her earthly life.

The night wore on. The yellow harvest moon rose high in the heavens, flooding the world asleep with her golden light. Silence reigned all over the pine and bamboo forest, and on the roof were 1000 men at arms, waiting. Then the night grew grey towards the dawn, and all hoped that the danger was over, that Princess Moonlight would not have to leave them at all.

Then suddenly, the watchers saw a cloud from around the moon and while they looked, this cloud began to roll Earthwards. Nearer and nearer it came, and everyone saw with some dismay that it laid its course for the house. In a short time the sky was entirely obscured, till at last the cloud lay over the dwelling only ten feet off the ground, and in the midst of the clouds stood a flying chariot, and in the chariot a band of luminous beings. One among them, who looked like a king and appeared to be the chief, stepped out of the chariot and, poised in the air, called the old man to come out.

‘The time has come,’ he said, ‘for Princess Moonlight to return to the moon from whence she came. She committed a grave fault, and as punishment was sent down to live here for a time. We know what good care you’ve taken of the Princess, and we have rewarded you for this. We have sent you wealth and prosperity. We put gold in the bamboo for you to find.’

‘I have brought up this princess for 20 years, and never once has she done a wrong thing. Therefore, the lady you were seeking cannot be this one,’ said the old man. ‘I pray you look elsewhere.’

Then the messenger called out aloud, saying, ‘Princess Moonlight, come out of this lowly dwelling. Rest not here another moment.’

And these words on the screens…and on these words, the screens on the princess’ room slid open of their own accord, revealing the princess shining in her own radiance, bright and wonderful and full of beauty.

The messenger led her forth and placed her in his chariot. She looked back and saw with pity the deep sorrow in the old man. She spoke to him many comforting words, and told him that it was not her will to leave him, and he must always think of her when looking at the moon.

[CT ends the reading]

I find it interesting that in no version of any story I can find does the figure of the moon woman stay married. Rarely she does get married, but it doesn't end well or last long. Mostly, like in this tale, she evaporates back to where she came. And this is revealing as traditional tales told by both men and women in history are often preoccupied with coupling up the heroes and heroines, but the moon child and her moon mother are always single and mostly virginal. Nobody owns the moon.

If the date in the tale struck you as familiar it’s because it’s the date of the Lunar Festival in Southeast Asia. On the 15th day of the eighth lunar month, moon cakes are eaten and the harvest is celebrated. Many people, when thinking of this date, would not think of Kaguya-hime and her story though, but the myth of the moon goddess Chang’e, as she is known in Mandarin. She has other names around China and Southeast Asia, and her story is not what I would call a fairy tale, as it’s a myth and a religious story, but the romantic elements make it very folkloric, and it’s often told like a fairy tale to children.

The story goes that Chang’e was married to the famous and talented archer Hou Yi, who shot down eight of the nine hot suns that plagued the earth and was rewarded with a potion of immortality. Hou Yi wanted to share the potion with his wife but, depending on the version of the tale, she either drank it without him or was forced to drink it so that their enemies didn't drink it.

But either way, upon drinking the potion of immortality, Chang’e floated up to live on a palace in the moon. The hut – with her pet rabbit, which can be seen in the moon to this day.

So this is the tale that’s at the heart of the Lunar Festival for many and you remember Chang’e and her rabbit, as Hou Yi did by offering up mooncakes and fruit. I do like mooncakes.

[indicates to presentation slide with picture of Chang’e and her rabbit on the moon] There she is.

And there are many more tales I could talk and tell you about tonight. I've tried to edit them down to the ones that are most famous, and the ones that I think represent the tales as a whole. From one story that I've spoken tonight about the moon coming to Earth, someone floating up to the moon, there were 15 other versions in various cultures. Every rabbit that ends up in the moon, there’s a fox or woman or a man eating cheese. It’s clear in our stories that we once saw the moon as an ultimate foreign country and always unattainable, and our cultural inheritance of these moon stories is predominantly in the figure of the moon maiden. There’s a celestial woman who falls to Earth, from Stardust to Sailor Moon, or to Elsa in her ice palace, far away from the bogles and the dark of the human world. And if you’re interested in fairy tales, there’s a great online resource, the largest collection of written tales on the internet, which happens to be a website called SurLaLune, or By The Light of The Moon. It’s easy to look up.

Thank you so much. Hope you've enjoyed.

[Audience applause]

Facilitator: Thank you so much for that, Clare. We have a few short minutes if anyone would like to ask any questions. Pop your hand up and I'll come to you with a microphone.

Yes, one at the front.

Audience Question 1: Thanks for that. Coming from the UK, there’s the mythology of the moon is made of cheese. Can you shed any light on that?

CT: Yeah. I didn’t go too into it ’cause it’s so specifically English and I fell down a bit of a research rabbit hole about the man in the moon in the cheese. But it’s all quite late. It’s 1600s onwards. And like the popularity of those nonsense rhymes in those pamphlets. And that’s really, it’s just, I find it so fascinating that everywhere else in the world but England and Brittany, are the only places that make the moon male and focus on the man in the moon. And there’s something just so cutely English, I think, about the man in the moon eating cheese, and about that mythology that – it’s often the way with, like, the best fairy tales. You can’t say why that’s English, but yet for me it does resonate. The man in the moon, the stories from Mother Goose and, I do, it’s also because there was this rush of publishing fairy and folk tales in England in the early…later than the Brothers Grimm. Brothers Grimm were incredibly successful. People like Andrew Lang and Joseph Jacobs realised there’s a buck to be made, and they started collecting tales, but they actually started with the rest of the world and came back to England late, and to Ireland and Scotland.

But there is something…it’s just so uniquely English, and maybe it’s just the great cheese in England. It’s such an important thing. Each region with a special cheese. I mean, in France too, I guess, but maybe that’s what it is. I couldn't find an answer for why the man in the moon is male in England and Brittany, and nowhere else. But I think it’s unique. And I think that's what I love about fairy tales is that stories can be similar, but there’s a cultural resonance to place, and that's why I try and like, attribute it as close to an area as I can. You know, there’s something about the dialogue of that Lincolnshire one, can’t be from somewhere else. Yeah.

Any other questions?

Audience question 2: I came in late, so I might have missed it. One of the ones said that the moonlight, was, was a forcefield against evil. So when I’ve been thinking that, lunatics, werewolves and that sort of thing, it's a thing of doom, where do those two come along? One is a force of good, and one is a force of evil.

CT: Yeah. I think it really depends which mythology you’re drawing on. You know, in…in East Africa, the night is the time of the good, day is the time of the evil. I think in a lot of cultures, the night was a cleansing thing, especially if you’re a peasant and you work hard in the field all day. The sun is hot, the sun is the enemy, and then the moon is this cleansing ritual. Werewolves, I could do four lectures on about, but originally they weren’t tied to the moon. That's quite a, like, a modern thing. And it's, I don't know, I think there's something about also the fact that werewolves were often male witches, or there were just as many men killed for doing werewolf magic or wolf magic as women in Central Europe. In places like Estonia and Switzerland, they had the werewolf trials, which, where they killed a lot of pagans by calling them werewolves. And so I wonder sometimes about the modern moon werewolf connection. I’d have to speak to a specialist, but I wonder if it is also about feminising those men. You know, those pagans that were said to be ‘other’. They’re connecting them back to the witchy moon, the cycles of the moon, which were all feminine energies.

But yeah, werewolves are very French. You know, in Russia they had werebears, you know, also they have werefoxes. It's wherever you go, it’s whatever the biggest animal is, that’s the ‘were’. But, yeah, I could, I'm happy to chat hours about werewolves. But it is, it really is in, like, the pagan or early cultures, the moon’s a cleansing force, and it comes…the dark is bad – bogles in the dark – but the night is not inherently bad. Yeah.

Facilitator: Wonderful. Well, that concludes us for this evening so thank you so much everyone for coming. And please put your hands together once again for Clare.

CT: Thank you.

[Audience applause]

[Recording] Thanks for listening to the Talks Archive brought to you by the Western Australian Museum Boola Bardip. To listen to other episodes, go to visit.museum.wa.gov.au/episodes/conversation where you can hear a range of talks and conversations. The Talks Archive is recorded on Whadjuk Nyoongar Boodjar. The Western Australian Museum acknowledges and respects the traditional owners of their ancestral lands, waters and skies.

More Episodes

Join Dr Natasha Hurley-Walker, ARC Future Fellow at Curtin University, as they explain how lunar radio waves let us explore the universe.

Join the stellar Sandra E Connelly and Dr Phil Bland in the To the Moon exhibition for a fascinating conversation about NASA's seven-billion-dollar mission to explore Earth, the Sun and beyond!

Join Richard Tonello as they discuss and debunk all things lunar conspiracy, from the flapping flag to flat earth theories, missing stars and the moon's reflectivity index.

Explore the realm of off-earth habitation and hear how plants can be engineered for space exploration and altered Earth climates.

A conversation between Dr Chantal Bourgault Du Coudray & Lucy Peach, discussing the cultural significance of the moon and how this relates to women.

Join Professor Steven Tingay to discover how the moon itself is a telescope for radio astronomers.

Join Professor Eric Howell in this talk that delves into the heart of multi-messenger astronomy, highlighting its potential to decipher the intricate mechanisms driving these cosmic phenomena.

Join Dr Robin Cook on a celestial journey exploring the mesmerising interplay of the Sun, Moon, and Earth

In this talk Professor Bland outlines the mission that Curtin is developing to find ice on the Moon in accessible locations.

Join Xavier de Kestelier, Principal and Head of Design at Hassell, to hear about Hassell’s design journey and collaboration with the European Space Agency to develop a innovative concept for a thriving settlement on the lunar surface.

Join Dr Benjamin Kaebe, an engineer, researcher and teacher, as he discusses the opportunities of a Western Australian space economy.

Professor Phil Bland provided an overview of Artemis, and what the next decade of space exploration might look like.

In this lecture, Professor Katarina Miljkovic explores the impact origin of the Moon.