Treasures of Thonis-Heracleion - The Myth, the Legend and the Reality by John Mirosevich

Thonis-Heracleion was Egypt’s greatest Mediterranean port for 400 years. Once, the gatekeeper to Egypt’s interior, the legendary city was visited by Paris and Helen of Troy and by Herakles. After being lost for 1600 years the city and myths were rediscovered buried under the Nile’s mud, exposing treasures from before and after Queen Cleopatra’s Ptolemaic Dynasty came to an end.

Committee Member of the Ancient Egypt Society of WA (AESWA), John Mirosevich has been a Science and Mathematic High School Teacher for 37 years, now teaching at Armadale Senior High School, and is a self-confessed “History Nerd”. John is fascinated by the Math and Science of the Ancient Egyptians, leading to his appreciation of this part of the world's history.

-

Episode transcript

[Pre recorded introduction] Welcome to the Western Australian Museum Boola Bardip talks archive. The WA Museum Boola Bardip hosts a series of thought provoking talks and conversations tackling big issues, questions and ideas and is delighted to be able to share these with you through the talks archive. The talks archive is recorded on Whadjuk Nyoongar boodja. The Western Australian Museum acknowledges and respects the traditional owners of their ancestral lands, waters and skies.

[Facilitator] Hello everyone! Welcome to Boola Bardip. I hope you have had a lovely night so far. Before we get started, I'd like to acknowledge that this is occurring on Whadjuk Nyoongar boodja and pay my respects to elders, past and present. Tonight we have the pleasure of hearing from John Mirosevich. He is a self-proclaimed history enthusiast, maths and science teacher.

We are hearing tonight of a lost city called Thonis-Heracleion. I'll hand it over to John to tell you more about it.

[JM] Thank you very much. okay. Thonis-Heracleion is a very complicated story. Throughout history, there's always been stories about this place or that place. From ancient times, there was probably the ‘big three’. There was the city of Troy, supposedly a legend. The city of Atlantis is a legend, supposedly, who knows? And Pompeii has been mentioned as well as being a place time forgot and there were many other places as well.

There were many stories told by these old storytellers. Homer, with his legendary book The Iliad, talking about the Trojan Wars and the Odyssey. Herodotus, who was basically an ancient day’s journalist - writing all sorts of stories, but, also prone to accepting bribes to extend how the story sounds, and Strabo who later on wrote about all sorts of different places.

The city of Troy was apparently somewhere near Canakkale, which is in Turkey. It was suggested to be in that area by Homer's story. It's been made famous by many, many movies and things. You can see the bottom images (on the powerpoint) are from the Brad Pitt and Eric Bana version of the story. This (powerpoint map) gives you a bit of an idea of roughly where it is, close to the Gallipoli Peninsula, and towards the Aegean Sea. Somewhere in there was the site of the famous Trojan War; where Ajax, Achilles and Hector fought…and the dreaded wooden horse. Here is a Mykonos vase from 670 BC showing the wooden horse and if you look closely at its feet, it doesn't have hooves, it's got wheels and you can see the little faces in the windows.

Throughout ancient times, the fantastic legendary story of the Trojan Wars was shown on vases and everywhere. It was all about heroes. I love stories about heroes. People wanted to know, was it true? Eventually they discovered in Turkey a place called Hisarlik. In Turkish it basically means ‘the place of fortresses’. They found that place, and archaeologists have dug through and there's actually multiple layers. There's like nine different cities of Troy. It was in a very, very important location, strategically. For whatever reason, the cities collapsed or were overrun and they built a new one, or maybe they didn't like the size of it and needed a bigger fortress and then knocked it down and built a new one. Who knows?

Schliemann (Heinrich Schliemann), was the person who originally started excavating, and dug down and found King Priam's treasure trove. You can see the picture there on the left. That was dug up from Troy ‘3’. They actually worked out that if any of the Troy's were going to be the one of legend, its actually Troy ‘6’. So all those wonderful artifacts are actually from the wrong time. But what's amazing is you can actually go visit this amazing place! There's some photos of Troy and its the walls. But when you have all these layers, it's a massive job for archaeologists to sort of dig through and try to work out is this part of 6 or 7 or 2? A very, very complicated thing trying to work out what's actually there.

In Pompeii, I took these photos in a place that was lost to history. Pompeii was in the Bay of Naples. You can see from Naples in the distance, Vesuvius, that dreaded volcano, which looks nice and quiet there, but as recent as 1944, it erupted and erupted quite badly. You can see how it's spewing out so much, materials, that it could cause a lot of damage. When I went there, we walked up the side, and had a look in the crater, thought it was nice. A nice hole in the ground but you just don't want to be around when it actually erupts! They actually found where the ruins (of Pomepeii) were, and they've started digging it up.

It's an ongoing process. There is so much of it still to be dug up. Three or four days ago, did anyone see this in the news? It was a fresco found in Pompeii, and it's the first evidence of pizza, fast food! There's the round table and just to the left, the round bit of bread with stuff on it. The journalists doing the story said there was no indication of whether there was mozzarella on top or not, but it's a pizza! If you've got bread, you’ve got stuff on top that’s cooked, it's a pizza. This is roughly what they think it (Pompeii) looked like at that particular time and they're still working that out because there's still bits of it that they haven't excavated. The Italian government is not putting a huge amount of money into discovering bits of the history, so it's a very slow process.

What they are finding is that the city was basically buried over a day, and people were caught. That dog, unfortunately was tied up and didn't get a chance to get away, so he perished. There are many bodies that they have discovered. I think more importantly you're seeing what everyday houses had; terracotta jars, what was in them. We discovered that the Romans actually liked beer a lot because evidence that the jars were were filled with beer. Others had olive oil or wine.So they’re discovering what life was like back then.

To Egypt now, Herodotus writes of Helen of Troy, who was taken away from Mycenae by Paris. In his writings, the original name apparently was Alexander, but I prefer Paris. So when Paris abducted Helen away from Greece, they didn't go back to Troy. They actually went to Egypt, because it’s a big drama stealing a king's queen, not nice. Some of the stories say that they went there and then moved on to Troy. Some say they went there and that Helen stayed while the Trojan Wars were happening for the ten odd years, but Paris had to go back and do his princely thing. The story mentioned that they went to the Nile River Delta, and it was at the mouth of the Canopic Channel. In 25 BC, Strabo also referred to the Canopic Channel, and about a city that was there called Heracleion, which had the Temple of Hercules there. Hercules is Greek, but hey… the Greeks were there as well.

This is what they think it kind of looked like, the reconstruction of what it appeared. They basically built it on the delta soil, and that became problematic later. This city somehow disappeared. It disappeared physically, but also disappeared from most writings. Not all writings, but it seemed to have disappeared. We’ve now found that it was actually a big, very, very important city. The reason why it disappeared, was because Alexander the Third, also known as the Great, came along and overtook Egypt. He became Pharaoh, went away to the Siwa Oasis, talked to the oracle and discovered something about his future. So off he went and conquered Persia, half of India, and made a big name for himself. One of the things he did for the brief time that he was actually in Egypt was that he found what was then called Phonis sitting on delta silt, which was not good, and declared that he wanted to build a new city just around the point where there was, only about 20 or 30 kilometres away, a solid limestone foundation, and the city of Alexandria was built there. Alexandria then became the capital and it became the capital, sadly not for him because he died quite young, but for one of his generals, his name was Ptolemy. When Alexander passed away, they sliced up the empire and different generals, got different pieces of the cake. Ptolemy got Egypt, and did well because he became the new pharaoh. Even though he was very much Macedonian, the Ptolemy dynasty actually lasted quite a long time.

That's the Ptolemy the first on the left. On the right is the last member of the dynasty, who we know very well - Cleopatra. Cleopatra the Seventh. She's the one who got together with Julius Caesar, and then Mark Anthony and caused all sorts of dramas. A very, very famous, family who did a lot for Egypt. Even though they were Macedonian, they actually took on the Egyptian lifestyle.

Egypt was an absolute powerhouse for finance and trade. Everyone wanted to trade with Egypt. When the Ptolemies came into power, they noticed one of the religious activities that they do; when one became a pharaoh, the Egyptians liked to party quite a lot. There was a coronation feast, and it basically lasted as long as it took for the Pharaoh to go and visit every important temple from Luxor all the way down to the Delta. They’d go to Luxor Temple and have a big feast, and then they’d move onto the barges and feast, it's just party time for them. It started at Luxor, and Luxor was the centre of religion for the ancient Egyptians.

When Alexander died, before Ptolemy really got into power, in that period of flux there was Philip the Third. Alexander's dad was Philip the Second, this is Philip the Third. I think, an uncle. I'm not 100% sure. He was the king of Macedonia, but wasn't very powerful or very strong, so didn't last long. One of the last things he did was to do the right thing by Egypt, and so every ruler of Egypt would go to the Luxor temple and build an extension. Every pharaoh likes to build an extension because then you get your face on the walls with the hieroglyphics, and, it's a bit of a publicity thing. So, he built the last extension in the Luxor Temple.

After that, when the Ptolemies took over, Luxor lost its power, okay, its religious power. The main temple of Amun, which is one of the leading gods of Ancient Egyptian religion moved to Thonis Heraklion. You can see there that the large temple with the flags flying. This is built on delta soil, which is not very good, especially because they used the big granite blocks.

It changed its name to Heraklion because that temple was not only in honor of Amun, but also for Hercules. The Greeks had, huge influence in the area. If you have all of these Greek sailors coming in and trading, if they go on a trip to Spain or Carthage or wherever, they want to make sure the gods are happy and look after the boat so they don't sink. You make an offering to the gods. The Greeks didn't really know this Amun god. So there was kind of that blending of gods. The temple became Amun Gharib, which was the name, but also it worshiped Hercules as well. So the Ptolemies then ended up changing the name from Phonis to Heraklion.

Now, when Alexander the Great did pass away, this sort of shows how revered Hercules was. On the right there is a Babylonian astronomical diary which has mentioned about the death of Alexander the Great. Then next to it there's this image of Alexander, and on his head is a lion's head. If you know all the stories about Hercules, he had 12 labors he had to do. He did something where the gods were unhappy, so to make the gods happy he had to finish these 12 labors. I could be here forever telling you about the labors. But the second or third was there was this big lion killing people, causing a whole lot of drama. He was sent to kill it. He slayed the lion, took the hide off it, and basically wore the hide because he thought it would give him the power of the lion. This is Alexander wearing the lion's cape that Hercules was wearing. It just shows that even Alexander the Great liked to be shown to have a link to Hercules.

Apparently, Hercules went to Egypt and killed King Busiris. Nowhere in the kings lists have we found any reference to a King Busiris, but in some of the stories that have been written by the storytellers, that they refer to this king, so whether it's true or not, who knows. At the moment, it's still legend.

I luckily had the opportunity to go to Morocco recently, and just outside of Tangiers is this place. It's called the Cave of Hercules. It's because in his travels, he was tricked by Atlas to hold up the sky. Atlas then had a bit of time, got around and did some stuff, but then Hercules tricked him back. Atlas then held up the sky, and Hercules was very tired and needed a place to rest. This is the cave that he apparently slept in. It's a really nice cave, the local tourist bureau assures us that's exactly where Hercules stayed. These old stories just like permeate all over the place. They pop up all over the place.

Now, the Trojan Wars. The dates don't quite match well with how the stories say that Paris and Helen were around Thonis Heraklion. So, this is where reality sets in, and we get this archaeological evidence of the date of these things and we can dispel some of the legendary stories. I still like to tell the stories, and this is a nice one.

In 600 BCE, Stesichorus wrote in his papyrus, which there's not much of the papyrus left, about Helen staying in Egypt. Basically, the temple at Thonis Heracleion was in honor of Amun, but also Khonshu who is the son of Amun. The Egyptian’s also called Hercules Khonshu, and this blending of gods just makes things that much harder to work out what what's going on. But by the end of it, they basically change the name of Thonis to Heracleion.

Me, being the science and maths teacher with a logical cap on, I think, where's the reality of all this? You can see the green ribbon of the Nile and the banks of the Nile, where the inundation each year used to flood and there's great agricultural land. At the top you've got the delta, and the delta was the breadbasket for Egypt. This is where most of the food was grown. This is where most of the trade was. If you look back at where a lot of the capital cities at various times were, they were found in the Delta and that's where the ships came in for trade.

Trade was important. Now, back in the day that Delta had multiple canals that were able to get from the one Nile River out into Mediterranean Sea. Over to the left, you can see where there's a couple of lakes. There is the Canopus. The Canopus was the deepest and widest canal, but for some reason, most of the early capital cities were over to the east. Those tributaries, all slowly one by one, because of human activity, because of agriculture, they suited up and they basically all got blocked up.

So from seven, they’re now down to two. Only two of the canals actually reach the Mediterranean Sea now. This is what they think they look like. Back in the day, the actual land that was on the surface is shown as orange, but the silting up thanks to erosion and weathering basically brought down a whole lot of dirt. Inundation hasn't happened for a while, but this is what it used to look like. The two obelisks over to the left, that's at Luxor. If you’re ever in Egypt, you go past them to go to the Valley of the Kings. The inundation, the water level gets right up there.

That was a problem in modern days. When the English were ruling over Egypt, they built a dam. In more recent times, the Egyptian government with the funding from the USSR, built the Aswan dam and that's basically dammed up the Nile, made the massive lake behind it, and stopped the inundation.

The inundation used to flood over the agricultural paddocks, little ones. But they would bring silt and organic material down, which was what they needed to be able to grow crops. For thousands and thousands of years, the silt and dirt that was washed down from Ethiopia on the Blue Nile would come in, lay on the paddocks and when the water dropped you’d plant your seeds in this freshly laid mud and you would get fantastic crops!

This is when they think the workers couldn't work because it was flooded, and that's when they would go and help build the temples and pyramids. That flooding back in the day caused liquefaction, basically turning the soil into quicksand if there's enough of it. There's a couple of examples of where different objects have gone under. We've got a very, very famous city (Venice), which is sort of like, trying to hold back liquefaction. When it gets high tide, the St Mark's square gets a lot of water. They're doing all sorts of things to try to stop that. Back in the days of Heracleion, they didn't have the technology to be able to slow it down. The city crumbled because of that liquification.

Probably the nail in the coffin for the city was, and this is when history books basically ceased to talk about Heracleion, was around 365 when there was a massive earthquake in Crete. It sent a tsunami across the Mediterranean. Apparently boats that were in the harbor at Heracleion were found 7 kilometres inland. It was a massive wave which basically finished off the job of destroying the city. The city physically disappeared and because of it was no longer a functioning port, it also was no longer useable by the governments of the day. Temple wise, I think with the loss of this temple the religious ceremonies possibly moved back to Karnet. Soon afterwards, the Romans would’ve been taken over and left.

Now, this is a map showing roughly where Heracleion is. Alexandria is on the dark brown there, next to that is Canapus. Near Canapus is a city on the seashore. Back in the day it was actually inland. Some of the suburbs of Canapus are actually submerged, but people basically forgot about Heracleion … Heracleion was further out. It wasn’t until 1933, RAF pilot doing a reconnaissance mission happened to be flying over the bay and noticed down in the water there was a lot of patterns. He could see through the water there was blocks and patterns. He reported it and people suddenly started taking notice.

However, it wasn’t until 1992, that this gentleman Franck Goddio , who is the president of the European Institute of Underwater Archaeology and also happens to have an interesting background, spare time and money, luckily for the world he is infatuated with scuba diving, archaeology in particular around Alexandria and Thonis Heracleion. He actually discovered it and is still working on the site today. They do underwater archaeology all over the world but his big focus is around Alexandria.

What he did was, he got three different types of scanning techniques. He basically got bathymetric maps, working out the actual lie of the land of the sea floor, then he would use the magnetometer to scan and look for metallic bits and pieces. He had GPS connected to all that so he could map exactly where different things were found and then using sonar. Overlaying those three scans he was able to work out where various bits and pieces were.

Here are some of the statues that they found, but the thing was a lot of these they had to go and find, because the Nile continued back in the day, for 2000 years, to inundate. You had silt, you had sediment pouring down through the Nile and it basically buried everything. Buried it between 1.5 to 2 metres of silt. If you’re s scuba diver fifty years ago having a look around, you wouldn’t see anything. It would just be mud. The occasional block sticking out, the big blocks from the temple, but otherwise you couldn’t see too much. But with those 3 scans he worked out “ahh this is where we need to do a bit of digging”.

The puzzle of the name. He wasn’t actually looking for a place called Thonis, because he has heard about Thonis, but there’s this other place called Heracleion. He was actually looking for two different places. He found though, when he was clearing away the silt, a stellae. A stellae is basically a poster from back in the day with important decrees and declarations put on there. On that particular stellae he found the Decree of Sais. It talked about how there was trade, and whenever trade comes into the city of Heracleion that the Pharaoh has the right to 10 percent tax on everything that comes in. Making sure the Pharaoh was able to get their cut. There was also forts and soldiers to make sure everything was kept in order, but in the top left hand corner if someone was to decipher it. The top little square its got “Thonis, the Egyptian name for Heracleion”. That was his epiphany for “ahh!” these two places are actually the same place”.

They found other stellae at Canopis, some of which were incredibly large. Just up the coast one of the stellae we know quite well, which is the Rosetta Stone. That had the key to being able to unlock the hieroglyphs. The ones in Heracleion were massive, massive stellaes. This one is so big that when it collapsed and broke they got the pieces together, got it out of the water and were able to reconstruct it.

Other things, statues which were reasonably intact. You can see that the legs were broken there but the Ptolemean king - they cant work out which one - is five metres high. A huge statue. The queen is 4.9, so a little bit shorter, but they are massive statues. All the things that Frank Goddio is extracting out from his archaeological underwater digs goes straight into the Alexandrian Museum. None of it is allowed to leave the country, unless its on an exhibition which he does do occasionally. You can see massive statues, but lots of other things also have been found.

Because the silt covered everything up, they’re digging up and finding amazing things. This golden plaque from Ptolemy III, which was stuck on he outside of some building. Its like this building opened by whoever, its in Greek, but solid gold! There’s a statue of the great-great grandmother of Cleopatra the Seventh. She was apparently Queen Arsinoe II. She was an absolute powerhouse in the Ptolemaic dynasty. The statue is incredible in its craftmanship and the silt protected it from being broken down.

Another thing they discovered, was coins everywhere. There’s a reason for that I’ll tell you in a minute. Gold coins, silver coins, Greek, Ptolemaic, Roman, Byzantine, Islamic coins; were all found in that area. So, there was activity in the area for quite a long time and stuff was being left in the water. Whether it was dropped accidentally, who knows.

Coin making was something that was done there, and they actually found this die which you put the metal in and belt it for some of the coins. They also found these lead pots, very large pots. Hopefully they weren’t using them for cooking, hopefully used for something else, lead not being the nicest thing to be eating out of. It’s a puzzle but they’ve found them intact. They’ve also found little lead toys; little elephants, a falcon and the strange long skinny things are their version of a toy boat. These were possibly given as offerings, like some jewellery.

We don’t know if these were accidentally dropped in, but there’s a lot of things that lead us to believe that they believed in the afterlife. If someone has passed away and you wanted to honour them, you make an offering to them. It happens to be in this particular area, in the days when the temple was up and running and the city was raging before it started to sink, a lot of people would give offerings to the Nile. The Nile being the sacred river, if you knew that ‘Uncle Charlie’ liked figs, you’d get a tray with some figs, offer it to the Nile and the Nile would carry it to the next life to Uncle Charlie.

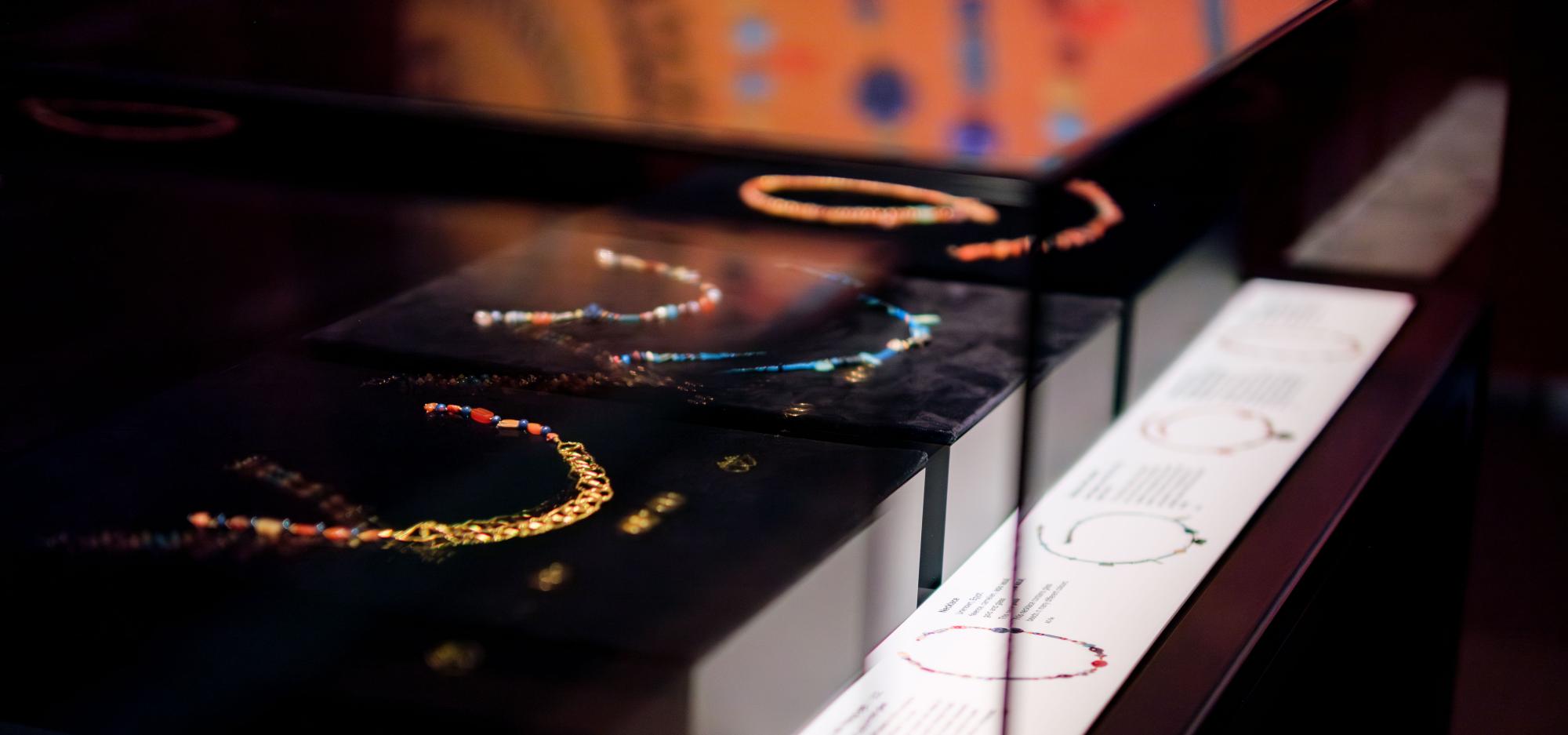

There was jewellery. Again we don’t know if it accidentally fell in, or was offerings. But some things do lead us to believe they were offerings. Outside of one of the sanctuaries, all of these little statuettes of Osiris; bronze and inlaid with all sorts of precious materials. They were all found.

On a side note, are the naos. A naos is like a pretend little temple. One of the ones they found closer to Canopis, so between Canopis and Heracleion was like particular one. It was called the Naos of the Decades. It’s the first humanly recorded calendar! It had a year calendar with 365 days. At the back of it were inscriptions which Nectanebo the First, of the 30th dynasty of Egypt, inscribed in their calendars.

Gold plates have been found. Offerings put into the plates possibly, into the water. These ladles which were ceremonial, not for soup, but for some religious ceremony. Some of these have been found – whether they were accidentally dropped and put in there on purpose, we’ll never know. This nice pectoral – gold and lapis lazuli – was found in there. That would’ve been a magnificent offering to one of your ancestors.

The other thing that’s really, really important about the finds in Heraklion are boats. This map shows blue diamonds as a shipwreck, and every blue dot is an anchor. Anyone whose a boatie knows you lose the occasional anchor. Hence why there’s so may anchors. A lot of the boats that’ve been lost there – maybe an occasional sinking by accident – but this particular boat its ‘ship 11’ on that graph is this ritual boat. Its made out of sycamore fig wood. It was used for a lot of ceremonies, but then at some point in time they decided that they were going to offer the boat itself.

We know this because if you have a look up there is a panel that has been taken out. Its actually been taken out, cut out so that the boats been released into the Nile and the slot that’s missing basically allowed water through and it sunk. When they excavated this from under all the silt, there was a whole lot of artefacts in it. Its was like a massive offering to the gods.

Boat ‘number 17’ kind of got squished under a whole lot of rocks. They think it was tied up next to the temple, the wall fall down and basically trapped the boat under the block and all the stuff in there basically was trapped. This particular boat was the first evidence of a boat with a keel which was centrally fixed. In an old-fashioned boat, a keel is the big paddle at the back and its on the outside. Sorry, that’s the rudder, but you have keep correcting it because its on its side. Herodotus in one of his writings, they thought he was making it all up, but he tlked about this boat that had a central rudder. They thought h was making it up, but there’s the evidence. Its actually got the hole where the rudder actually came through the centre of the boat which saved a lot of dramas.

Another thing they found was this little hessian bag tied up. Inside the bag was someone meal! It was maybe a lunchbox of a worker, or maybe it was an offering to someone and they wanted to give him a lunchbox in the next life – we don’t know. This bag was found and we got to see what ancient Egyptians were eating at that particular time. The fruit was there, the grains – and that was only found recently, only about 5 or 6 years ago. Mainly fruit.

Its one thing about Heracleion they’re finding out what life was like in ancient Egypt. Unfortunately, the archaeologists just like with Troy, have got layers of stuff they need to sort through. The Byzantine era was there, some of their stuff was left there. The one that was really interesting – a little French fella named Napoleon – he took over Egypt, and sent his fleet into Egypt. The British didn’t like him sending his fleet into Egypt, so there was a bit of a battle and he took Egypt, but he lost the sea battle. The L’Oriente, which was the flagship of the French navy at the time, got sunk and its pretty well GPS, right on top of where Heracleion is right now. So you’ve got these layers – French bits of boat, then you dig further and there’s so much there to discover.

If you’re interested in Heracelion, Franck Goddio’s website is updating all the time. They’re finding stuff all the time! They’ve only discovered like one tenth of the city, there’s so much more to find there. Hopefully we’ll find out so much more about what life was like back then.

And that’s it!

[Pre-recorded outro]

More Episodes

Listen to Hon Dr Anne Aly MP who joined us at Afterlife Bar for a presentation on the Discoveries of Ancient Egypt exhibition.

Join committee members of The Ancient Egypt Society of WA Inc for a unique opportunity to dig deeper into Egyptology.

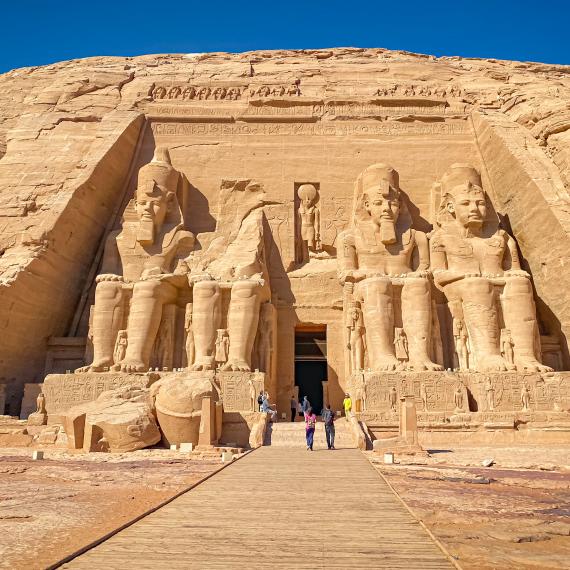

Dean Kubank revisits the Temples of Nubia and the enchanting Temple of Isis at Philae.

Celestial Timekeeping in Ancient Egypt - Discover how Ancient Egyptians used the heliacal rising and setting of stars to construct their star clocks and civil calendar.

The life of the average Egyptian could sometimes be precarious and short. Broken bones, infections, and arthritis were all common among the general population.

Discover the story of the pharaoh Djedkare, his family and courtiers, and take advantage of the rare opportunity to hear from visiting international Egyptologist Dr. Hana Vymazalová of Charles University, Prague.

Discover the story of the pharaoh Djedkare, his family and courtiers, and take advantage of the rare opportunity to hear from visiting international Egyptologist Dr. Mohamed Megahed of Charles University, Prague.

Discover Egypt’s ancient legends of creation, death and resurrection. Tales of Ra, Osiris, Isis and Horus will unlock the meanings of the art, religion and funerary practices of ancient Egypt.

The Dynasty 6 Vizier named Weni the Elder, who lived about four and a half thousand years ago, had a detailed biography written on the outside of his tomb.

How, when and why was mummification invented? The answers may surprise you.

Ancient Egyptian Astronomy Unraveled - Discover how the Ancient Egyptians used their knowledge of the sky to design and position their temples, statues, and roads.

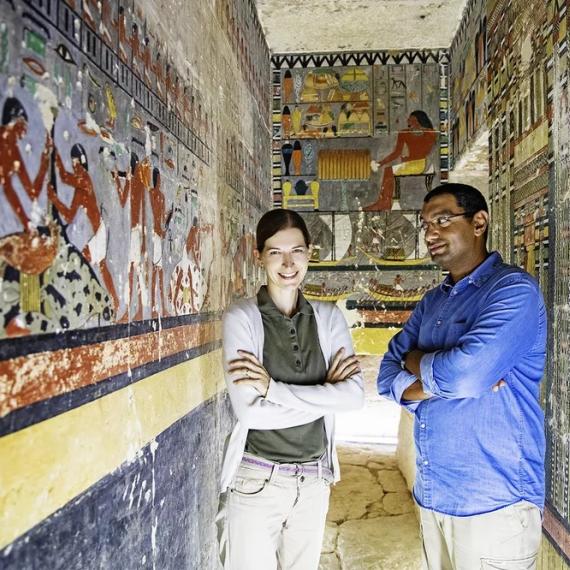

As part of our evening Afterlife Bar series at WA Museum Boola Bardip, we welcome a series of speakers to dive deeper into Egypt. Join us this week as we hear from Dean Kubank on Temples and Tombs.

Renowned expert in ancient Egyptian history Daniel Soliman delivered a fascinating talk, as we celebrated the launch of the WA Museum Boola Bardip's Discovering Ancient Egypt exhibition.