Meet the Museum: Cats and the Conservation Estate

Navigating the delicate balance between the preservation of the Conservation Estate and our cherished and loyal feline companions is both a challenge and a responsibility.

Heads up, unfortunately this podcast cuts out before the end. There’s still plenty of great content, so please listen and visit ReWild Perth’s cat resources for more information on how to keep your cat safe and happy at home:

- ‘Keep my cat indoors from now on’: https://rewildperth.com.au/resource/keep-my-cat-indoors-from-now-on/

- ‘Keep my outdoor cat away from wildlife’: https://rewildperth.com.au/resource/keep-my-outdoor-cat-away-from-wildlife/

In this session of ‘Meet the Museum’ you’ll hear from conservationist Hannah Gulliver from ReWild Perth and cat behaviourist Dr Heather Crawford discussing ‘Cats and the Conservation Estate’.

Hannah will share the mission of ReWild Perth, a community movement who are gardening for wildlife in Perth, to create a greener city where both we humans, and the unique flora and fauna can coexist – and of course, our pets! Navigating the delicate balance between the preservation of nature in our cities, the Conservation Estate, and our cherished feline friends is both a challenge and a responsibility. Cats undoubtedly bring immense joy to the lives of many, becoming loyal companions and cherished family members. Dr Heather will bust the myth that cats must roam free to live their best life and will guide you through how to provide the most enriching life for your cat while keeping them safe and content within the comforts of home.

Join the movement to help ReWild Perth and bring nature home, visit www.rewildperth.com.au

Meet the Museum

Are you curious about the fascinating world behind the scenes at the Museum? This monthly program delves into the less visible parts of the Museum’s work, as scientists, researchers, historians and curators share their expertise and passions.

-

Episode transcript

[Talks Archive introductory music playing]

[Pre-recorded introduction]

You’re listening to the Western Australian Museum Boola Bardip talks archive. The WA museum Boola Bardip hosts a series of thought-provoking talks and conversations tackling big issues, questions and ideas. The talks archive is recorded on Whadjuk Nyoongar Boodja. The Western Australian Museum acknowledges and respects the traditional owners of their ancestral lands, waters and skies.

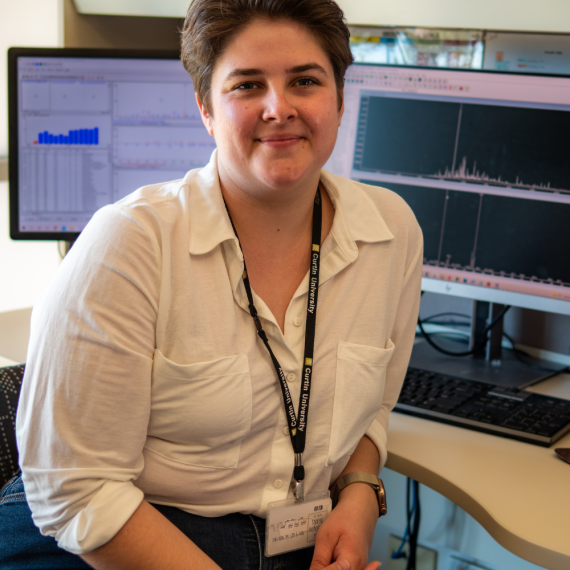

Hannah Gulliver: Kaya. Hello, I'm Hannah Gulliver from the ReWild Perth team at Perth NRM.

Thanks for tuning in to this episode about cats and the conservation estate, proudly supported by the WA museum Boola Bardip and our major supporter Lottery West.

A quick heads up that unfortunately, our recording from cat specialist Heather Crawford's presentation cuts out before the end. There's still plenty of fascinating content ahead, and you'll be able to explore a wealth of online resources about local wildlife and tips on responsible pet ownership by visiting rewildperth.com.au.

All right, let's dive in. I'll start by giving you a quick intro to ReWild Perth, a community movement creating a greener, more connected city that supports all of its residents, wildlife and humans alike. Then I'll hand over to our special guest, cat specialist doctor Heather Crawford.

Perth is a city blessed with incredible natural spaces, from stunning bushland and wetlands to beautiful coastal reserves and parklands. And let's not forget the jewel in our city's crown Kings Park Botanic Garden.

Now, while we cherish these green pockets critical to supporting wildlife, they are often disconnected from one another, making it hard and dangerous for wildlife to move throughout a city and to find the food, water and shelter that they need to survive. So beyond conserving these natural areas, what's the solution?

Well, did you know that residential land makes up about 80% of Perth's greenspace? Imagine the potential of these gardens to support wildlife providing habitat stepping stones to connect these critical remnant patches.

Rewild Perth is here to help you transform your outdoor spaces into havens for both you and our local wildlife. Together with BirdLife Australia and thanks to support from Lottery West and the Water Corporation, we've created an awesome online resource. Our website offers a library of actions and guides by creating a free account, entering your suburb, garden size and pet ownership details. You received a personalised free wild action plan.

Living in an apartment? No worries, you might be encouraged to pot up some wildflowers or add a bird bath/. If you have a large property we’ll suggest trees, plants, and structures you could install.

You can explore our library featuring plant profiles matched to the dominant soil type of your suburb, with gorgeous photos and growing guides. There are habitats, structure guides for bird baths, nest boxes, ponds, frog hotels, and more, all with designs, installation and maintenance tips.

Plus discover sustainable rewilding actions including responsible pet ownership. You can also discover the local animals that visit your garden and how best to support your garden guests.

Each animal profile will have links to the plants, structures and actions that will support that particular species. We also team up with experts, organisations and local councils around Perth to host engaging talks, walks and hands on workshops.

To, to find out what's coming up and to add your garden to the growing network of nature links throughout our city, you can visit rewildperth.com.au today.

Now let's focus on today's topic: Cats and the Conservation Estate. We all love our feline friends, but when they roam, they can have a significant impact on wildlife. Cats killed tens of millions of native animals each year in Australia, including birds, frogs, insects, reptiles, quenda or bandicoot, possums and small wallabies.

This can be a tricky topic, but we're thrilled to have cat specialist doctor Heather Crawford with us to share how we can create happy, healthy home environments for our cats while protecting the wildlife that call our city home.

Heather works in the environment, conservation and agricultural and veterinary departments at Murdoch University and is the consultant for the Cat Haven in Subiaco. With over 20 years experience working with wildlife and domestic animals, Heather has worn many hats from wildlife Rehabilitator and veterinary nurse to zookeeper and ecologist.

Her PhD thesis focused on managing stray cats in Australia, and she enjoys collaborating with diverse stakeholders to better manage stray, feral and pet cats. Heather's passion lies in animal welfare and behaviour and finds that cats are the perfect study species for exploring the links between these.

I can't wait to hear what Heather has to share. Over to you, Heather.

[Audience applause]

Dr Heather Crawford: Thank you. What a great introduction. Thank you for coming along today. I know it's been a scorcher outside, so I think you've been like me and sat in the traffic sweating to get here. But isn't it nice and cool inside?

I really appreciate you coming out and attending this event. I'm also so incredibly grateful to the museum and to ReWild for sponsoring me to come to talk about cats and wildlife, which are two of my favourite topics, and in this case they’re combined.

So I'm really interested in what you have to say, but what I'm hoping is that I'm actually going to teach you a little bit, so you’re going to walk away with a bit of information that you didn't already know about your cat, and maybe even a little bit about the wildlife that's living in Perth at the moment, and which we're hoping to preserve with initiatives such as ReWild.

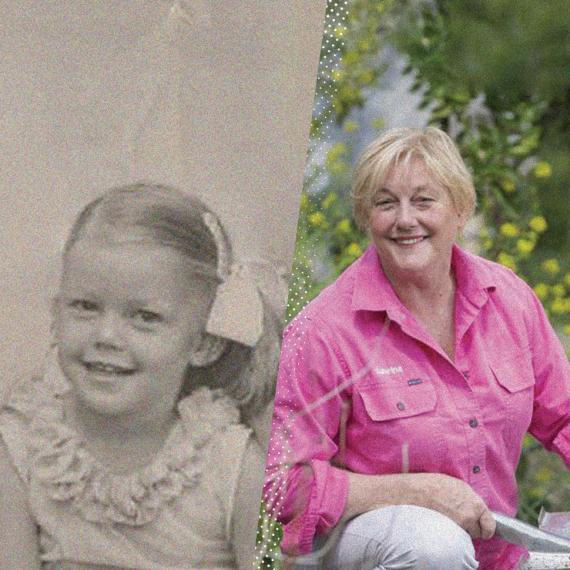

Before I jump into the science of it, if you will, a little bit about me: So I'm originally from South Africa, but I've been in Australia for a long time now, so I'm very much, adapted to the culture here. But I've been very privileged. I've managed to work in several countries, and I've worked with everything from insects to giraffes.

And I've come back to cats again and again and I ended up doing my PhD thesis on the management of stray cats. And of course, when you work with stray cats, you end up talking about pet cats, and you end up talking about feral cats as well and the fact that they have they live along this continuum in our environment.

But I'm basically wanting to assure you here that I have a lot of knowledge about cats, but I also have a lot of knowledge about wildlife. So, in addition to that, what I've been able to do is bounce between my favourite subjects. So I've been able to go wildlife, cats and dogs, wildlife, cats and dogs and I have done a lot of pet sitting, a lot of pet counselling, if you will, and I did consult for the Cat Haven as well on cat behaviour.

This is the magnificent creature that owns me [Heather shows a picture of her cat on the slides]. His name is Zimba. And in this glorious picture here, he has what you can see is a sort of collar under his fluff there [points to neck]. It's also got a long aerial coming out of it.

So he was being tracked by a colleague of mine who was doing her thesis on the movement of cats in suburbs and he was volunteered against his will to go into the study.

He didn't really like having the collar on him, but he adjusted pretty quickly. And she gave me a map at the end of it and this is what it looks like {Audience mutter as slide is shown of an arial shot Heathers suburb with lines indicating the vast movement of the cat].

Now, my cat in my mind, wasn't a big hunter. And when he brought home animals, they tended to be rats. So I thought, he's not going far. He's not doing much. Then I got this back. With the collar he was wearing the green dots [pointing to slide]. And without a, a device, which I'll talk about in a little while, The anti-predation device, he was wearing the red.

And apart from the fact that it was very clear that the collar made no difference to his behaviour the thing that jumped out at me was that he was crossing some very, very, very busy roads and, even though it's suburbia, people, you know, speed down those roads and straight away I started thinking, hmm… maybe I can do better.

And more importantly what is he getting up to? Why is he going that far? And why is he pretending that he's sleeping all day? Because that's clearly not happening, right? This has all got a time point associated with it. I knew that he was out there and up to mischief.

So it gets you thinking… how many people here have cats? [Audience members put hands up]. Great! How many people love that cat? [Audience put their hands up] Alright we’re winning because some people are just like, I want to get rid of the cat, can we get rid of the cat, please?

I think you can only appreciate a pet when you understand where they came from. And so you'll often hear dog people saying, well, dogs are better than cats because there's so much easier to understand. You know, they really make a lot of sense. We've obviously evolved with them for a long time.

It's very true. It's very true. In fact, dogs actually have micro muscles in their face and they've evolved those micro muscles to communicate with us because we're not very good at communicating. We're not very observant. But the dogs realise that we were talking with our faces, and so they've evolved these little micro muscles so that when you look at a dog you know he's smiling, you know he's looking sheepish, you know he wants to play.

Look at a cat face… well… they look a little bit indifferent most of the time, don't they? Maybe amused if you trip over, but they tend to have ‘that’ face [Audience giggles] right? Okay? And there's a reason for that. It's because we've evolved with them. We've domesticated them, but not in the same way that we've done dogs.

So dogs have actually been around for a 100, 000 years following people around. And about 20,000 years ago, we started breeding them for specific purposes. Hunting, pulling sleighs, you know, guarding sheep, that sort of thing. Cats. Totally different story. They've evolved in the Middle East, okay, and their association with people is directly related to our development of agriculture.

So in that area [refers to a map of the world on slides] we have 16 different grains and legumes have naturally occur, including wheat, barley, chickpeas and that meant that people started storing these food grains long term. So normally you'd have a season but what they figured out is you can put it in a silo and you could actually have this food all year round. And where there are grains, there are mice and there are rats.

And up in the mountains lived the ancestor of our domestic cat. This is the African wild cat [Pointing to slide of African Wild Cat]. So they've done DNA studies. We know that this is its origin, but this species still exists today. It's completely solitary. Lives up in the mountains, doesn't bother anybody. Only come together when they want to mate.

But what happened was as soon as we started storing grains around the joint, these cats started realising that there was a source of food for them year-round as well. Those rodents. And where there were rodents, there are also snakes and cats are also specialist snake hunters.

So I don't know if you've seen those videos where a cat sees a cucumber on the floor and they freak out? That is a snake reflex. So they’ve still got this inbuilt reflex for cats and rodents. It takes a lot of skill and very fast reflexes to deal with either of those species.

So the reason why they’ve still retain that is because they've come from an ancestor cat that specialises in that. That's what they eat in their native range.

But I don't know about you, but those cats kind of look like my other cat that I had up until last year. You wouldn't really be able to tell the difference, would you? So the importance of DNA is really, come to the forefront when studying animals like dogs and cats, because it can really tell us a lot about where they came from.

So the reason why I'm babbling on about this is because your cat will make more sense when you consider that they've evolved in an environment where they don't need a lot of water, so we provide them with water, but technically they get all their water from their prey.

Rodents are their preferred prey, so if they are in the environment, they will preferentially go for rodents. That's what they have evolved to eat. The other thing that's really interesting is that they're completely solitary, except when they're breeding and that still defines a domestic cat.

But what's happened is that we live on top of each other in high populations, which means that we now have pet cats living on top of each other in high populations and we take away they need to reproduce by dissecting. And that's like the best thing you can do, because for them, being on top of each other can be quite stressful.

But the process of domestication is making them more willing to live with other species, including dogs and birds and fish. You see all those wonderful memes with dogs, cats, birds all on top of each other now. So the domestication process is carrying on.

The other issue that the, the ancestor cat brings up is the fact that they have high infant mortality. Now, if you live in a desert and you never see a male, and then one that you see a male and you mate, you have as many babies as possible.

And you are prey size so eagles eat you, foxes eat you, wolves eat you do other things eat you. So you have lots and lots of babies. So that means that when you bring that into a suburban setting, it means that your pet cat, if you don't sex it, it is able to have between 4 and 8 kittens up to three times a year. So the reproduction, the ability of the cat to repopulate is incredible, It can't be understated. And that hasn't changed with domestication. Apart from the fact that we, we neuter it. So does that make sense?

I'm hoping I'm going to get you excited about your cats biology because they are unbelievable creatures.

I want to return to the DNA just very quickly to show you that the studies have been done. So here's the origin section. And then about 2000 years ago, we started branching east and west through to Central Asia and all the way up into Britain and then they had these questions about, you know, how, how long ago did we take cats to Australia and to the Americas? And we now know that Australian cats have only been here for 200 years. So they actually came on the first fleets that were requisite.

They had to be on the, boats for insurance purposes to make sure that rodents were being controlled on boats. So that was a global policy and it meant that everywhere merchant ships went, they took cats with them and they took rodents with them. And this meant that not only could cats get off the ships and be sustained by the food that came with them, but they could also take advantage of all the native species that were already there.

And this means that they've perfectly adapted to hunt animals other than rodents. So they will not hesitate to take reptiles, insects, frogs… and they love birds. But then, of course, high densities with us, they are very, willing to scavenge if they need to. And that's often something that's seen when there's high populations of them. When there's not a high population of cats, they easily sustain themselves by eating just wildlife.

But a cat in need will actually scavenge as well. So you can, in some places, consider scavenging to be a central part of the food that they eat every day.

And boy, did that travel influence our own culture. We love cats, we love dogs, but we love cats. And they hold this kind of godly place in our culture.

And a lot of money was always spent on cats, you know, dogs had a purpose. Cats willingly came to us and then happened to be quite good at controlling rodents. Other than that, they we're pretty much left to themselves. It wasn't until 200 years ago that we actually specifically started breeding different cat types with each other for specific features.

So again, I'll remind you, with dogs, we started at least 12,000 years ago, cats 200 years. So we're still learning about cats. And I can tell you that these find creatures along the bottom here [points to a slide of varying cat breeds] are the result of turning on only two different genes. So we go from that striped tabby in the desert, you turn on two genes and you can end up with all these different varieties.

So we're still learning just how complicated these animals are. But what we've had, what we've adapted the cats for specifically is; we wanted them to be good hunters of rodents, but we also wanted them to be friendly, to allow us to breed them with each other and to have them in the house and not attack children or dogs or other people.

We are slowly getting them more used to the presence of other cats. And this is really interesting. And you will see this with your own cat. They develop a language just for you. So the language that you have with your cat is completely different to the language that I would had have if I came and pet sat for you.

The cats are actually manipulating us. I hate to say it, but they're very good at it. Feral cats, caps that are living in the wild and that African ancestor. They do not make the same vocalisations that our pet cats do today.

And if your pet cat becomes a feral cat, if it goes and lives out in the wild again, it just stops making those noises.

So we have got our own individual, one on one, relationship with our cat and that has resulted in this specific, vocalisation manipulation. And then, of course, we also adapted their fur colours and their face shape, for their style and for fashion.

But importantly, moving forward, what they have retained is what we call a cryptic nature; their willingness to hide, to observe, to watch, to not be the centre of attention unless they want it.

They like to be sneaky. the breeding output that I mentioned again, so this, this ability to just produce lots and lots of kittens, an aversion to conflict. So what I mean by that is there are some species that when they get confronted or there's a bad moment of stress, their inclination is to fight. Cats, their inclinations to run away.

And that's something that, so if you if you're a solitary animal living up in the mountains, but it also works really well when you're living in suburbia, where there's lots of other cats who all want your territory.

So when you're handling cats. And so that certainly in the visionary practices that I used to work in, if you're manhandling a cat, their first inclination is to run away. It's actually not to scratch you, if you've got to scratch point, there are some problems… we’ve skipped a few stages there.

And then the two that I've put asterisks next to here [gestures to slides], the two features that I've put asterisks next to is this concept of hyper carnivory, prey drives and reflexes. So by breeding them for hunting efficiency, we've ensured that they've maintained the willingness, the skills, the ability and the desire to hunt. That's not gone yet.

And then hyper cone every that refers to the fact that these animals cannot be vegetarian, they cannot be vegetarian. They are unable to produce amino acids that regulate eye function, kidney function, liver function.

So they have got to eat meat. And we haven't evolved away from that. It's not going to happen. Dogs actually are able to digest carbohydrates. Cats are not.

And if you've been a long-term cat owner, you will have seen a shift in cat food being wheat based and now it's being advertised as free range, whole meat based. And that's because they're realising there are all these behavioural problems and physical problems that come with eating carbohydrates.

So those are two things to keep in mind as we go forward now when I start talking about bit more about wildlife.

Okay, so we've got an issue. Often it's presented to you in the media as a choice. You can have cats or you can have wildlife. You can't have both. And I'm here to tell you, you can have both. Just requires a little bit of creativity and a little bit of understanding about your cat and what your cat needs.

And then with the resources such as ReWild, they actually give you the information about what the native species need as well. So we can tick all the boxes and you can have both things. You don't have to compromise.

Okay, so let's get into some science for a little bit and hopefully none of you will fall asleep. But a colleague of mine, the same one who put the collar on my cat, did a massive survey around the world and asked lots of questions about cat ownership.

And this one really caught my attention because they asked ‘Is the fact that your pet cat killing animals? Is that a problem to you? How do you feel about that?’ And it was really interesting across these very large, these countries which owned quite a number of cats, there was quite a range in attitude, whether they were cat owners or non-cat owners. People were very split. You know, some people are very worried. Some people are not worried at all.

What was really interesting is that Australia, most people actually are aware of the problem and they think it's a problem whether they're cat owners or not cat owners. So that's really encouraging.

The bad news is that when we've done surveys about what people actually do with it, cats, very few people actually keep them indoors and indoors might be, you know, restricted to they go out and or kept inside the apartment.

Most people actually just let their cats come and go and so that's the area where we're, we're targeting presentations like this to try and encourage people to bring their cats indoors. And I want to give you some reasons why it's a good idea. But the first thing that we need to address is the elephant in the room, which is that yes, yes, yes, all these cats are big problems, but not my cat.

And I know what this feels like because I showed you my cat made me go through the same process. Oh, it's not my cat. I was studying cats and I went through the same process, so bear with me. Okay, there's a few reasons why people think that cats, their cat, is not doing the things that I've just mentioned.

The first one: he sleeps all day. No he doesn’t. He doesn't sleep all day and getting more and more science now that actually shows exactly what cats are getting up to.

So everything from accelerometers, which are little devices like your Fitbits that monitor whether you're jumping up and down, running, climbing stairs, through to cameras on them, which are actually looking at what they're doing.

And a study that they did with accelerometers showed that if the cat wasn't sleeping or eating, it was basically sleeping. So there you have this contrast. Well either it's doing lots of things or it's sleeping a lot, it doesn't matter. The point is that when that cat is up, it is active, it is switched on. And so whatever opportunity comes in front of it, it's going to take advantage of it.

So I like to call it the hour of power because even if your cat's only up for an hour, he might go next door and decimate a population of Kwenda or take three nesting, nestling birds out of the nest. So in that hour your cat can do a lot of damage.

So is probably a good thing that it sleeps a lot because if he was hunting 12 hours a day we would be in big trouble. Okay, it's like the equivalent of having a lion on the Serengeti. We can, we can take a lot of animals off very quickly. Okay?

There are physiological reasons why they sleep all day. and makes a lot of sense, especially today in a hot, hot, hot day like this. You want to sleep? Okay, so it does make sense why they do it.

But the important thing is that when they are awake, they're able to do quite a lot of damage to the environment.

The other idea that people like to think about the cat not being a hunter is the fact that you feed them like a good quality diet. I feed my cat, he's actually fat, he eats too much, you know, there's no way he needs to go and hunt, for survival.

And that's very true. You've taken away that need to hunt for survival. The cats don't only hunt for survival, they hunt to practice their skills so that they can teach the next generation if they have to. And they have to vary their diet in accordance with the environment around them.

So whether, as I said before, whether they're surrounded by rodents or whether they're surrounded by insects or whether they're surrounded by birds, whatever, in an environment, there's an opportunity for them to practice their hunting.

So they may not eat it, but they're going to hunt it.

Okay. And the reasons why they do this is because when you live in a desert, the food is very ephemeral. Sometimes it's there, sometimes it's not.

And so it's really beneficial if you can swap between food types as they disappear. So I just try to illustrate that on the graph here [Gestures to slides] with the rodents which tend to, you know, explode after rains. Their numbers will go up and birds will go down and cats will very easily swap from one type of prey to the other.

The other thing is that they're opportunistic. So anything that scuttles across the floor. It could be a cockroach, but it could also be a ping pong ball and that's how you get your cat to play. You're taking advantage of that opportunistic and willingness to hunt.

And then this was a surprise to me and I love it because it blows people's minds. We think of feeding dogs as you give them, you know, half a kilo of food and then nosh it all, and then they go and sleep. That's not how cat’s metabolisms work. Cat’s metabolisms are for every hour that they are up. They need to eat every 20 minutes. So when they've done laboratory trials, these cats have actually eaten between 12 and 28 meals a day.

So you might only feed your cat once a day. But your cat's metabolism wants food regularly, so it's actually better for cat health, and the vets are getting on board with this now, especially when it comes to urinary health, If you provide your cat with free access to food and they can graze at will like a big buffet […]

Hannah Gulliver: Thanks for joining us today. Unfortunately our recording ends here. For more information, visit rewildperth.com.au to join the community movement and bring nature home.

[Talks Archive outro music playing]

[Pre recorded outro]

Thanks for listening to the talks archive brought to you by the Western Australian Museum Boola Bardip. To listen to other episodes go to vist.museum.wa.gov.au/episodes/conversations where you can hear a range of talks and conversations.

The talks archive is recorded on Whadjuk Nyoongar Boodja. The Western Australian Museum acknowledges and respects the traditional owners of their ancestral lands, waters and skies.

More Episodes

Gender-related violence isn’t talked about often enough, but it happens in WA. Often, conversations centre on victims and perpetrators, warning signs and cycles, breaking points and crises. But what happens next? How do we move toward recovery, reconciliation, and positive change?

We know ferns have existed on Earth for millions of years, but just how closely do ancient ferns resemble modern ones?

By drawing on First Nations knowledge systems, cultural practices, and research methods, this presentation will showcase how climate adaptation and mitigation strategies that respect and integrate Indigenous knowledges and practices can help sustain well being.

Have you ever wondered what it is like working with fossils every day? Helen Ryan from the WA Museum shares her work in discovering, uncovering, preparing and preserving ancient life.

Hear from Dr Amanda Ash from Murdoch University’s School of Medical, Molecular and Forensic Sciences as she delves into the complexity of parasites and their importance.

Join us for a journey into the ancient world with Dr José Galán, a renowned Spanish Egyptologist and director of the Djehuty Project.

Curious about the creators behind our Megalodon head in the Wild Life gallery? Join the makers from CDM: Studio and peek behind the scenes as they share their process of designing, building and delivering museum exhibits.

Discover what we can observe about the Moon, learn about our current knowledge, and understand the importance of returning to its surface!

Discover the elusive Night Parrot at WA Museum Boola Bardip! Join us for an exclusive panel discussion with experts Penny Olsen, Allan Burbidge and Rob Davis.

Join Museum experts Jake Newman-Martin and Linette Umbrello as they take us on a mammalian adventure of the minute kind, from tiny marsupials to giant megafauna.

Discover the remarkable story of Wayne Bergmann, a Nyikina man and Kimberley leader who has dedicated his life to his community, in this moving memoir of living between two cultures.

Celebrate Perth Design Week with a robust panel discussion focusing on design and business.

Talk series hosted by Geoff Hutchison that explores who our young selves were and what became of them. This week hear from Sabrina Hahn.

How much will we look to the language of activism in finding the way towards reconciliation in Australia?