Meet the Museum: Fun with Fossils

Meet the Museum

Are you curious about the fascinating world behind the scenes at the Museum? This monthly program delves into the less visible parts of the Museum’s work, as scientists, researchers, historians and curators share their expertise and passions.

-

Episode transcript

[Recording] You’re listening to the Western Australian Museum Boola Bardip Talks Archive. The WA Museum Boola Bardip hosts a series of thought-provoking talks and conversations tackling big issues, questions and ideas. The Talks Archive is recorded on Whadjuk Nyoongar Boodja. The Western Australian Museum acknowledges and respects the traditional owners of their ancestral lands, waters and skies.

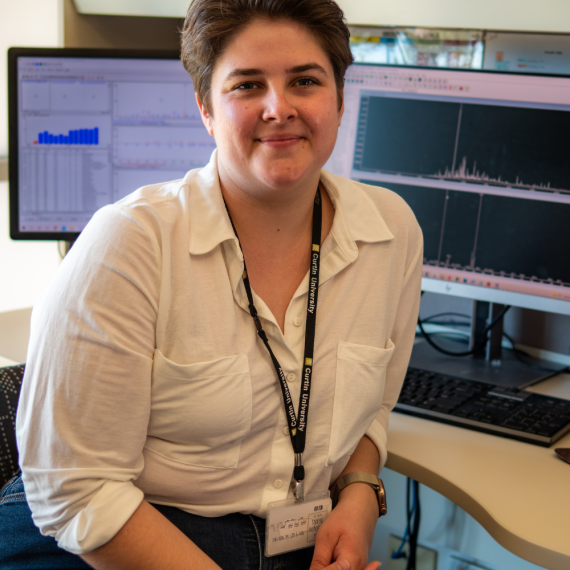

Helen Ryan: So, thank you for that. As mentioned, my name is Helen. I work in the Collections and Research Centre in Welshpool, so I get to play with all the fossils that aren’t on display. So most of you would be familiar with the Portals of the Past gallery upstairs, and all we have on display up there are the highlights of the state collection. So, the bits and pieces from the most significant fossil sites, like the showcase quality stuff. But this is, like, not even 1% of what we have in the entire collection.

So this is the Collections and Research Centre in Welshpool, and this is where all of our collections are kept, not just for palaeontology but across the museum, and it’s also where our labs and our offices are. [shows presentation slides] So it’s where we conduct all of our research and we take a closer look at our specimens.

This is the palaeontology collection. [shows presentation slides] So we’ve got rows of cabinets where we store our fossils. We’ve got 1.5 million specimens in our palaeontology collection, and it covers 3 billion years’ worth of Earth history. So we’ve got everything from the earliest stromatolites, all the way through to material or animals that died only a few thousand years ago. So we’ve got stromatolites, plants, invertebrates, vertebrates. We have trace fossils, so things like footprints and burrows. You name it, we’ve got it. So I’m responsible for looking after all of those specimens.

So this is what it looks like in the drawers, and this is basically the final product. So once specimens have been collected and prepared, they’re put away in the cabinets and they’re left there until researchers come along who are interested in whatever taxa, and they’ll come out and they’ll have a look. They’ll compare what we have with specimens from around the world and figure out exactly what they’ve got.

One of the best ways of getting fossils is fieldwork. And so today I want to go through various fieldtrips that we’ve done and then what we do with the fossils when we get back from the field. So, our main fieldwork that we do at the moment, we go every year up to the Southern Carnarvon Basin, which runs basically from Exmouth all the way down straight to Kalbarri, and what we have there is Cretaceous marine sediments. So 100 million years old and it used to be underwater. So in the ocean, so 50 to 200m deep depending on how far through the Cretaceous it was. Since the Cretaceous, we’ve had sea level changes. We’ve also had a bit of uplift and erosion. So now sediments that were on the seafloor are exposed on the surface again, but now they’re full of fossils and we can go and collect them.

So we have things like plesiosaurs – which is the one on the top – mosasaurs, ichthyosaurs, and then we’ve got invertebrates like ammonites and belemnites. [shows presentation slides] We just walk all the outcrops and see what we can find. So when we’re walking, we’re looking for larger fossils like vertebrae and other bones from marine reptiles. It’s a bit harder to see the smaller fossils, but it gives us a good overview.

This here, we have a couple of shark vertebrae that we found. [shows presentation slides] So when we find bones like this, first thing we do is we very, very carefully walk around the site. So we want to make sure that there’s no other bones or there are other bones, but we don’t want to crush other bones that might be there. So if we’ve got a couple of bones like this, there are more. So we need to have a very careful look to see if we can find any more and we haven’t missed any.

So once we’ve gone for a little walk around the surface, we then get comfortable. We sit on the ground and we just sift through the very top layer of sediment to make sure there’s nothing sort of hiding just underneath the surface, and we’ve probably spent a few hours doing that. And then once where we haven’t found anything for a while, we get the sift out and we put the topsoil into the sieve and we shake it around, and then we can find the really tiny bones like the digits of plesiosaur – oh, sorry, of ichthyosaurs get very small, and also small broken bone fragments, and we collect them all in the sieve and we put them all aside.

Once we’ve done through the topsoil, we can start our proper excavation. So this is getting closer to what you’d expect from a paleontological dig. [shows presentation slides] The yellow peg that you can see in the background is marking the highest point that we found a bone on the surface, which means that the skeleton is weathering out from above that point. So we start our pit. The lowest part of the pit is where that peg is, so the highest part. So we dig into the slope to see if we can find where the critter is weathering out of. Sometimes we find it, and sometimes we spend days and days and days digging a beautiful pit and we don’t find a single bone, so it’s a bit hit and miss sometimes. Sometimes we get to the skeleton as it’s finished weathering out, so there is nothing left within the slope.

The other downside is that this site is actually on a cattle station, and cows are not palaeontologists and they don’t really care. And they just walk straight over the skeletons and they crush them up. So a lot of this stuff would have been broken just by cows or whatever walking across the outcrops.

Another way we look for fossils up there. [shows presentation slides] So that’s looking for the bigger fossils, and then we’ve got the smaller fossils. We’ve got things like shark teeth, which I’ve actually brought some today, that are on display up here if you want to have a look, as well as things like invertebrates like belemnites. So we get down on our hands and knees, because if you’re closer to the ground you can see the smaller fossils, and here’s [inaudible] and this is actually pretty cool. This was easy to spot. We got two shark teeth right next to each other. It’s like winning lotto, really, when you’re looking for [inaudible]. It’s not normally that easy. This one here is a ptychodus tooth. Which is a, so a ptychodus is a type of shark. Instead of having teeth around the jaw line, it’s got rows of teeth on its palate. So it’s made for crushing things like ammonites and bivalves and hard shelled organisms for its diet. So you really need to get your eye in to see those. As you can see, it blends in quite nicely with the little nodules around. It just has a little shimmer.

So, typically, this is what we see. [shows presentation slides] This is the ground. And in this picture is a shark tooth. It’s a bit hard to spot, so I’ve circled it. Can you see it yet? [laughs] So usually we’re just crawling around really slowly, we’re like scanning across the surface, until something catches our eye and they can be quite difficult to see.

This is my love. [shows presentation slides] These are belemnites. So, belemnites are a squid-like creature that lived in the Cretaceous. They’re not related to the squid, but is the closest sort of type of animal alive today that we can compare it to. And the only thing that’s preserved in a belemnite in Western Australia is the back end – so, the pointy end of the belemnite, which are these rostrum here, and I’ve actually brought some with me if you want to have a closer look. But these are fun to collect because there are so many of them. I can collect bags in a day. You can see the bigger ones from walking around, but because there’s so many, it’s easier just to crawl around and fill your bag. Also, when you crawling around, you can find the really small ones, and I’ve bought some of the really small ones in today as well. But there is some here. So, these are about the bigger ones in this picture are about 15mm. So these are really small and you do need to be close to the ground to see them.

So the other thing we do is look for microscopic shark teeth, and you cannot see those. There’s no amount of crawling that will get you to see tiny shark teeth. So we have to collect samples. [shows presentation slides] So here we’ve got one of our volunteers, Reece, digging while our lovely head of department is sitting back having a Red Bull. This is what we use volunteers for. So, Reece is digging a trench. So we’ve got to get through all of the weathered surface at the top, we got to get down to the fresh stuff underneath, so that we can get to the really good rocks. So here’s a trench half dug. This is another one of our volunteers, Lincoln. So, we’re not that mean. We get our volunteers to rotate. They do ten minutes each, and then they go with surface collect, and then they come back and do another ten minutes.

Once we’ve dug our trench, we then bag it up really carefully. [shows presentation slides] And as you can see, we mark whereabouts we got it from. So usually there’s a mark of edge. So you can’t really see it in this picture, but there is a nodule bed coming through here. So those measurements are taken from that mark unit so that we know exactly how far in the samples were taken. Now, these bags weigh about 15kg each, and we have to get them from the field to the vehicle. Sometimes the vehicle is maybe 2-300m away, so we just carry it like a little baby. And other times, it’s a bit further. [shows presentation slides] So this is actually in Kalbarri, the closest we can get the car to the site in Kalbarri is 2.1km. I measured it. We’re not carrying it like a baby. We’re not even going to get to the top of the hill by carrying it like that, so we put it into backpacks and we go for a hike, and the beer is well-deserved at the end of that day.

So when we get back from the field, we’ve got to clean everything. So every single one of these bone fragments is cleaned with toothbrushes and dental picks. You get all of the sediment off it. Sometimes you get things like gypsum that grow on the bone or in little cracks in the bones. We’ve got to get all of those out. And then to stop further deterioration of the bones, we then have to coat it with stuff called polyvinyl butyral or paraloid, and it’s like a glue that holds it all together. It’s like a protective surface for it. Then we can play around with them without worrying about damaging them. So, here is the process of trying to piece the bones together like a jigsaw puzzle. [shows presentation slides] So we’ve got all of these broken bone fragments. We know they fit together somehow. So it’s just a matter of trying each piece against each other to try to see what, how they fit together.

Now, the sediment samples – the bags that we carried – they get dried out for a while until they’re completely dry. Then they get processed through a clay washing machine to get rid of all of the silt and very fine grains, and then we’re left with this residue on the right. [shows presentation slides] So it’s basically iron oxide grains and glauconitic, bits of quartz and whatever, and you can actually see here bits of fossil. So they all get picked out and examined. We also get lots of shark teeth. I actually took this photo this afternoon. I didn’t have time to find a shark tooth. But it’s an example. And this is what the tray looks like. So each, that square is 1 centimetre square. The golden square. So all of those samples get picked through by hand under the microscope. Then all the teeth that are collected from that, plus all the teeth that are surface collected, then get studied and described. When we describe them, we need really nice pictures. So because a lot of our teeth are really small, we use a scanning electron microscope to take images of them. Unfortunately, we’ve only got a small scanning electron microscope, so even some of the smaller teeth will require several shots. So I take multiple shots of the tooth, I pan across, then I stitch them all together in Photoshop, and then we’ve got some really nice pictures. I wasn’t allowed to show you a picture of the final plate because it’s not published yet, but it’s beautiful.

Okay, now this is what I do. I’m an invertebrate palaeontologist, so bones are fun and all, but invertebrates is where my heart is. So these are some of the belemnites that I collected on the last trip. [shows presentation slides] So when I get back, I short them all out into the different sites that they were collected from and I pull out all the really good ones and all of the sort of not so good ones I put aside. So they’re all the ones in the bottom. And then I get, sort through them further. So these are some of the smaller ones that you saw on a previous slide, and I’ve sorted these out into species so that we can describe them. So we’ve got two different – we’ve got one species on the top and a different one on the bottom, and I’ve just started work on that this week.

And so with photography of belemnites, when we publish, they’re way too big to stick in an SEM but they’ve also got really fine markings on them that you can’t normally see with a normal camera. So we use a normal camera, but we coat them with ammonium chloride. So it’s just like a fine powder that we heat up and then we use like a pump on the end of the tube, and it just puts the powder over the belemnite, and then you get all of the finer details will come up and you can see them nicely in publications. So that is the Cretaceous marine work that we do.

Staying with the invertebrate theme, there’s the Nullarbor Project. So this was fieldwork out on the Nullarbor. So, earlier I mentioned that we have our collections in Welshpool and all of the stuff in there is there for researchers to have a look at some point. About 50 years ago, the previous, one of the previous curators of palaeontology collected some snails from the Nullarbor. Didn’t think too much of them, but thought enough of them to bring them back and he put them in the collection and that was it. Fast forward 50 years, myself and a colleague, we were going through the collection and we came across these snails. And when we realised that they were from the northern parts of the Nullarbor, we thought, ‘that’s pretty far inland for land snail.’ Because most of them like wetter environments around the coast in sort of more mesic areas. So we thought, ‘let’s go on a fieldtrip.’ So we did.

We went out to the Nullarbor and we smashed open some rocks and we found more snails. So this is a bit different because, to the previous fieldtrips. The Carnarvon Basin stuff, we’ve got to be a lot more careful with. They’re a lot more fragile. These snails are encased in rocks. So out with the sledge hammer! So this gets fun. So we smash it open with a sledge hammer, that breaks it down into smaller bits, and then we get our geo picks and we smash them into even smaller bits, and then we find snails. So we did this. We did two trips. Because we had so much fun the first time, we thought, ‘let’s do it again!’ So we went back, we got lots of snails and then we brought them back, cleaned them up, we took photos of them, we took some measurements of them, we compared them with other species and discovered we had a new species of Bothriembryon. Just the land snail. And it’s also the oldest in Western Australia. And that was published earlier this year, and I’m quite proud of this because it’s my first first-author paper. So that’s my little bragging moment.

Anybody see this in the news? [shows presentation slides] Operation megafauna. No? Yes? So, back in 1991, the museum went up to Du Boulay Creek, up near Karratha – and so it’s about 100kms southwest of Karratha – to retrieve a Diprotodon skeleton. And they did that and when they came back, they’re like, ‘there’s at least half a dozen more up there. We’ve got to go back.’ So it took quite a while to get there because it wasn’t a cheap trip, but we ended up partnering up with Citic Pacific, which is a mining company that operates up there, and we went back. So we went back first to see if the ones that the museum reported back in the 90s were still there because 30 years is a long time. They weren’t there, but there were dozens of other ones freshly exposed. So we got to go for a dig!

Now, this is the typical palaeontology dig. [shows presentation slides] This is like almost Jurassic Park style, except it’s a Diprotodon and not a dinosaur. This was a lot of fun. And so in this case, we’ve got a beautifully articulated Diprotodon. So we’ve got the spinal column still intact. We’ve got the legs sort of still in position. Everything’s connected up. The last thing we wanted to do was separate it. We didn’t want to pull the bones out one at a time and get it all mixed up. So what we had to do was jacket it, so make a plaster jacket. So the first thing we had to do is dig around the skeleton, make a little trench, make what we call a mushroom. So it’s basically getting all of the dirt out from around the bones and underneath it to raise it on a pedestal, or down on a pedestal.

Once that had happened, this is one of my favourite parts of the job. If you love getting your hands dirty, this is excellent. So there’s our little mushroom at the bottom. We’ve covered it in paper towel, wet paper towel, and what that does is protect the bones from the plaster, because it’s really hard to clean plaster off bone so we put the protective coating on there. On this particular trip, so this is this time last year and it was hot. We’re talking like 43, 44 degrees every single day for two weeks. The plaster would dry in about 20 minutes flat. So we had to work fast. So it had a bit of a production time going. So we got the paper towel on the mushroom and then, over here, you can see her hands. [shows presentation slides] This is Cassia. She is getting Hessian, strips of Hessian, she’s making them wet, and what that does is it allows the plaster to soak up into the Hessian a lot faster. She then passes it to Kayla, who was dunking it into the plaster, and then Kayla would pass the plaster strip on to me, and I would put it down. So it was just a continuous cycle. We managed to get this done in about 15 minutes. Then the plaster went dry, we had half a bucket of set plaster.

When it’s done, we end up with an egg. So you have from a mushroom to an egg. So we let it dry so it gets really hard, and then we flip it over so that it’s off the pedestal so we can lift it up out of the ground. Then we have to get it from the field, without a forklift, to Welshpool. So it took six people to lift this particular one onto the back of a little buggy, which then took it to a ute, and then we had to drag it onto the back of the ute, and then we had to take it all the way to the mine site so they could get it into a container and bring it back. So it’s very hard work, but very fun and very satisfying.

Other skeletons weren’t so pretty. They were a little bit jumbled. So the best thing to do with these ones was to take the bones out of the ground one by one but we mapped them. So we had like a diagram of where the bones came from, and we wrote notes for each individual bone, and they all got wrapped in bubble wrap, boxed up and put on a pallet and sent back to Perth.

So back in Perth, this is the jacket that you saw a couple of slides ago. [shows presentation slides] It’s been flipped over and we’re working from the bottom up. And so, at this stage, all we’re doing is getting all of the loose sediment out of it, using just manual hand tools, so brushes and geo picks and sharpened screwdrivers […] And then this is after one day’s work, and as you can see, we’ve got some tooth rows coming out. So over the next few weeks, we’ll get deeper and deeper into that. All of this white stuff that you can see around it, that’s like the cement stuff. It’s really, really hard, and to get through that, we’re going to have to use heavier, heavier duty equipment like pneumatic scribes, which are like industrial strength engravers.

The bones that were brought back individually – I’ve got one over here actually – we clean up using dental picks and toothbrushes, and then once again, any cemented stuff on there that will come off with the pneumatic scribes. And we’ve got hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of bones to clean, and it’s going to be a very long time, but the end result is going to be a beautifully prepared Diprotodon. The one that was collected back in the 90s, that one took somebody full time one year to get that prepared. That was 40 hours a week, and that’s upstairs on display.

Megalodon! [shows presentation slides] Who likes a megalodon? Yeah? So does anybody remember about five or six years ago, there was a tooth stolen from the Cape Range National Park? So because that happened, the Rangers actually contacted us at the museum and asked if we could go out and do a survey so that we could record the location of all of the teeth. Well, as many teeth as we could. And they wanted us to collect a few so that we could put some on display up at Cape Range, we could put them on display in the museum, and we could also do some research on them.

So we went up there, and this was the first fieldtrip I went on where we were making finds every five minutes. So we were walking around the limestone and finding teeth stuck in the limestone like this one. [shows presentation slides] So this is the first one we found. This one took maybe about half an hour to find, but after that it was like, ‘oh, here’s another one, here’s another one, here’s another one.’ I was the note taker and I was run off my feet. I’m like, ‘can’t anyone else take notes?’

So once we recorded them, we weren’t there too long and we only explored a small area. We found 33 megalodon teeth and we also found a bunch of tiger shark and lemon shark teeth as well. So we suspect it might have been a feeding ground.

So then we had to remove them from limestone, which is not easy to do because limestone’s really, really hard. So we had to use a rock saw. But the problem is the rock saw requires a garden hose, right? But there’s no garden hoses in Cape Range National Park. So we got a pressure sprayer and we hooked it up. [shows presentation slides] So Lincoln on the right. So on the left, he’s there pumping away at the pressure sprayer to get the water flowing and then Jeff is doing the cutting with the saw. As you can see, there’s bottles of water in the back and we had to carry those for about a kilometre from the car out to the site, backwards and forwards with all this water. Another good workout.

So these are a couple of the teeth after they’ve been cut out to do acid prep. So fortunately, limestone dissolves in acid, but the teeth do not, which means we can put the limestone into a bucket of acid and it will erode away the limestone around it. So this is our acid lab set up. [shows presentation slides] So we’ve got a few going on at the moment.

So, caving. So, this is, like, all the more modern stuff. So Pleistocene aged to Holocene aged animals. So caves act as pitfall traps. So a lot of the caves, you can get into them but you can’t get out of them. So animals be like running along having fun and then they drop into a hole, and if they don’t die on impact, they can’t get out and they end up starving to death, or they might die of their injuries later on. And then the beauty of caves is that they’re naturally climate-controlled. So there’s very little disturbance, which means that the bones, or the carcass decays but the bones remain. The other good thing about caves is that because they’re there for a while, everything accumulates. You do get sediment washing in and it makes new floors and so you can get a record of how fauna changes over time.

So some caves are really easy to get into. [shows presentation slides] So this is the cave in the southwest, I think this one’s Nannup Cave and you can just walk into it. Not all the way, because there’s a locked gate there. You need permission. Other caves – this is more of your pitfall cave. So this is just a hole in the ground and we’ve got the abseiling rope tethered to a tree so that we can get into the cave. And at the bottom of this cave – this is Foundation Cave down in the southwest – at the bottom of that hole is like a mountain of bone from all these animals that have just fallen in there. It’s insane.

Some caves are a little more difficult. So this is Horseshoe Cave on the Nullarbor. Yes, there are a couple of trees there, but they’re not very good trees. We can’t tie ropes to them. One, because they’re a little too far away from the cave, and two, they would snap. So what we did was we go out the car, we reversed the car up near the cave and we tethered a ladder to it. So we don’t have a lot of pressure on the car but the car’s enough that that ladder’s not going to move. And we used a ladder to get into that cave. So we enter the cave, we get spoiled by beautiful cave decorations and it’s very distracting, and then we realise we have bones to find.

So this is inside Horseshoe Cave. [shows presentation slides] So one way that we collect bones in a cave is by trenching. So you can see the trenches in the background just there and there’s a better image. These trenches were actually dug in the 1970s and when the trenches are dug, they do 10 centimetres at a time. So they do 0 to 10cm, they collect everything from there, they bag it up, put it aside, then they do the next one, and it’s very carefully done. This cave here was over two meters deep, back in 1970. When we went back in 2021, it was only 1.2m deep. So that’s how much sediment had washed into the cave. But you can see that the rocks and stuff that had been placed around the top, they’re still there, but the sediments basically just gone in into the lowest point. Whole floor is covered in bone. It’s the, you’re walking across it and it sounds like popcorn because you’re just walking all over them. So when the sediment does wash in, it preserves what’s there and then it just makes a new floor.

So this is what the box of bones looks like. [shows presentation slides] From here they just get bagged up and put away sorted out those different elements and then an expert will come along. So somebody that works on quolls might come along and they’ll go through and they’ll pick out all of the quolls. And then somebody who works on bandicoots will come along and they’ll pick out all of the bandicoots and so on until we’re left with stuff that’s [inaudible].

Anyone seen this one before? [shows presentation slides] Yeah? So there’s actually a documentary on YouTube that was made back in the early 2000s called Bone Diggers, and it tells a story of one of the digs I did in the cave out on the Nullarbor. And this is a Thylacoleo and this was found by one of the museum digs, and this is the same one that’s on display upstairs. But this one, this is when it was first discovered. Now this is like 40,000 years old and when it was discovered, it was almost pristine as a skeleton. But if you touch it, because it’s so old, it would just turn to powder. It’s basically just being held together simply because it’s been untouched for 40,000 years. So to remove this from the cave, what they had to do was use the same stuff I was talking about earlier – the polyvinyl butyral or the paraloid – and they’d sit there with paint brushes and they’d very carefully paint one side and they’d flip it over, and then they’d paint the other side, and then they’d put it carefully into a box, carefully out of the cave, and then bring it back to Perth so it could be prepared better.

So this is basically how these sorts of skeletons end up. So we can’t really clean these bones. We do like to have our bones looking nice and clean, free of sediment, but if we do that with these bones, it’s just going to destroy the bone. So we’re better off keeping the sediment on the bone and just making sure it’s properly stabilised. So we go through and re-stabilise them so that they’re a little bit stronger. We can do, we can do a better quality job in the lab than what we can on the cave floor. And then we have to go through and sort them out. And these are one of my favourite jigsaw puzzles. I love doing this stuff. First thing I do when I find a box like this is I sort it all out into different elements. So put all the limb bones together, I put the lower jaw together, or the ribs together, or the cranial pieces together, and once you get your eye in, you can look at a bone fragment and you can sort of tell what part of the body that comes from. So you put it with that group, and then you can go through that smaller, smaller group of bones and figure out how it all fits together. So, obviously, the limb bones are the easiest and some of the ribs can be quite easy. The hardest part is the skull.

So this is the skull. [shows presentation slides] So what I do here is stabilise every single piece properly so that when I’m playing around with them that they don’t crumble or break. I then get a reference skull from the collection. Fortunately, we have quite a few Thylacoleos in our collection. I think we’ve got about 11. So I get one of the better preserved skulls, and that’s like my picture on a puzzle box. So that’s what I use to match all the little bone fragments up with. And after a while I end up with something like this. [shows presentation slides] So this is a few weeks work. Once I found two pieces that stick together, I put a thin amount of glue on, hold them together and I sit there and I’ll wait until I can let go of that without bones moving around. Then I have to let it cure for 24 hours before I can try to put another piece on. So it’s a very slow process but fortunately, while I’m waiting for it to cure, I can go do other stuff. So it’s not like this is this only thing I do in that time.

So after a while, this was the finished product for this particular skull. So I still had many bone fragments, but the bone fragments I had left, I couldn’t actually attach to anything because there’s missing pieces. I normally don’t like missing pieces in a puzzle, but it’s acceptable for this situation. So that’s the process of a skull jigsaw puzzle.

So it’s not fieldwork unless you can tick a few boxes. This is one of our beautiful campsites. [shows presentation slides] I love it out there, it’s so nice. There’s no children, it’s so good.

[Audience laughter]

So we have picnics. Every day, we get a picnic in a different spot, except in this top picture because we took a gazebo out and that was our picnic spot for the week. Campfires and a bit of camp cooking. That meal was amazing. It was so good. No, it’s capsicum and tomato thing with sausages and potatoes, nice. Night sky out in the field. You’re away from the city. There’s no light pollution. It’s amazing. On the nights where you have a full moon, it’s also really cool because you get moon shadows. And I’ve never seen a moon shadow in Perth but you go out there and it’s like, ‘oh my God, I’ve got to shadow at nighttime!’

Rain! You got to have rain on a fieldtrip otherwise it’s not a fieldtrip. [shows presentation slides] And it looks cold. It wasn’t that cold, it was just very wet. Flies. [shows presentation slides] The one on the right, that’s Du Boulay Creek last year. There were so many flies there. We actually filled a jar for our entomologist in about a day and then we forgot to bring it back.

Lizards. They’re the highlight of any day. So many different types of lizards out there. We even get the big perenties out there as well, which is really cool. Snakes. [shows presentation slides] This snake actually nearly fell on me. I was sitting at the bottom of a gully, and I heard this start and I looked over and about a metre away from me was a snake and I don’t think I’ve ever run so fast in my life. I did not take that photo.

Spiders. I love spiders when they’re in a web in their habitat. I don’t like spiders when they’re running around my house, but out here they’re beautiful creatures.

Flat tires. We have to take two spare tires out with us on every fieldtrip, because you’re going to get a flat.

And my favourite: fossils. So [inaudible] fossils in our collection, many I hold dear to my heart. This one here, you might recognise from the title slide. [shows presentation slides] This is my first ever jigsaw puzzle. So I got to work one day and my boss, Michael, gave me a bag of bone fragments and said, ‘put it together,’ like, ‘okay.’ And that took me quite a while because I was new in the job. So I started in 2009. This was in about 2010 that he gave me this puzzle. It took quite a while because I hadn’t even seen a vertebra like that before, let alone in pieces. So, it was a very good learning experience and that’s when I fell in love with paleo puzzles.

I love this one because it’s invertebrates and trilobites. [shows presentation slides] I love trilobites. So we’ve got a couple of trilobites at the top, and then we’ve got this little army thing, which is a Echinocaris, which is related to the Anomalocaris, and they actually ate trilobites. So this one here was about to have lunch, but then it did not.

This one here, it doesn’t look like much, but it tells a really cool story. So this is a Gogo fish. Has anyone heard of the Gogo formation? Yep? So the Gogo formation is in the Kimberley and it has fossils of 380 million year old fish. And these fish are preserved three dimensionally, so they’re in nodules, so they can get prepared out of the nodules by acid preparation. They’re three dimensionally preserved, so they still hold their shape. They’re not flattened at all. And they preserve soft tissue, which is the most amazing part. So 380 million year old musculature and embryos. And that’s what we have here. [shows presentation slides] Materpiscis is mother fish. This is Materpiscis attenboroughi, and it was the first Gogo fish described that had embryos inside it. It’s the earliest evidence of internal fertilisation. I love that because it tells an amazing story.

And this one, again, doesn’t look like much. [shows presentation slides] It is a belemnite. And this is the fossil that got my boss to say to me, ‘Helen, you were right.’ So I love it. Several trips, up in [inaudible] and I was finding these belemnites and they looked different to the belemnites that I was finding everywhere else. And I’m like, ‘I’m sure this is different.’ And he goes, ‘no, no, no, it’s just a preservation. There’s a lot of variation in belemnites. It’s still a dimitobelid, but it’s just a preservation thing.’ And then I found this one which has this little groove in it, which dimitobelids do not have. So it’s actually a completely different family of belemnite to the ones that I’d been collecting. And it’s undescribed from Western Australia. So that’s probably my all time favourite fossil at the moment.

And that is it! So if you have any questions at all, please let me know. Hope I didn’t talk too fast. [laughs]

[Audience laughter]

Facilitator: Thank you very much, Helen. Can we have a round of applause?

[Audience applause]

Facilitator: Fascinating. And we do have lots of time for questions, so I’ll come round, and if you just speak into the mic, that would be great. We’ll start here.

Audience question 1: Thank you. Trilobites. I lived in Canberra and where Parliament House stands now on Capital Hill, I found trilobites […]

HR: Nice!

Q1: […] all over the place, but I haven’t got one. At all.

[HR laughs]

Q1: You said something about not being allowed to show a photograph or […]

HR: Yeah, so, when things are being researched and they’re getting, and they’re not quite yet published, we’re a little bit restricted as to what we can share, because some things need to wait until they’re actually published before we can share it with the rest of the world.

Q1: So what I want to ask you is today in Boola Bardip, I saw the fossils of Banksia, leaves and Banksia nut from place east of Servantes.

HR: Yep.

Q1: How were they found? Was it in a mining site or […]

HR: I’m not sure as to the history of that site but usually to find fossils, yeah, mining companies will find something and they’ll let us know, or they might not let us know. But a lot of the time, we look at geological maps and we see where there’s exposure of certain aged rocks, and then we go out and we see if there’s anything fossiliferous in them. And sometimes there is and sometimes there isn’t. So yeah, it’s just that site, I know people have been collecting there for a long time but I’m not sure exactly how that one was discovered. But I do know the one you’re talking about.

Q1: Thank you.

Audience question 2: Sorry, I just wanted to ask, what is the process of figuring out, when you find the fossil, how do you figure out what species it is?

HR: So we compare it with other species from the same genus or from the same family. So, in the case of the land snail, we had a look at other species of land snail that was from the Nullarbor and also from Central Australia that were fossils going back a long time right back into the Miocene. So those ones were about 20 million years old. But they were in a different state but because they had sort of like a temporal similarity with ours, we compared them all together and by taking different measurements so we could measure the height and the whirl count and the size of the aperture and all that sort of stuff, and we plot them all on a graph. We do certain statistical analyses. It’s very complicated stuff, I’m still trying to get my head around. But they plot out in different areas on that graph and because ours plotted out in a cluster on its own and was separated out from the other ones, we knew that we had something different.

Audience question 3: You know, as an avid collector of fossils in England, where the rules are ‘what you found, you kept’, what are the rules in Australia regarding fossils and where would you report an interesting find to?

HR: Okay. So it depends on where you collect or where you go. So private property, you need to get permission from the landowner. National parks, you need to get a permit. Very hard to get so never collect anything in a national park. And you usually also need to get permission from the traditional owners as well to be able to collect. So a lot of the time, if you collect something and you’ve got the right permits, you can keep it. There’s no obligation to give it to the museum. The only thing you have to give to the museum, if you find it, is meteorites. So if you ever find a meteorite, you have to, by the Museum Act of 1972, give it to the museum and if we don’t want it you can have it back. But that doesn’t happen often.

[Audience laughter]

If you want to export it, you need to get, or if you want to export fossils, you need to get a permit. So you need to contact Michael at the museum. And if that particular fossil is well represented in museum collections, then you’ll be allowed to export it. Otherwise, it’s got to stay in Australia.

Audience question 4: I know it’s more of a silly question, but what sort of rocks do you find fossils in? I mean, you can go on something like GeoVIEW or TENGRAPH and you can get geological maps. So is it in, are they in granite, are they in greenstone?

HR: So you want to look in sedimentary rocks, so things like siltstone, mudstone, sandstone, greywackes. Granites are igneous rocks, so they form below the ground and they don’t have fossils in them because they’re basically made out of magma. But yeah, you need to be looking at the sedimentary rocks. So the rocks that are derived from other rocks.

Audience question 5: So looking at your photos, it’s still a fairly manual process. I imagine a lot of the things that you do today would be pretty familiar from people 50, 100 years ago. Is there any sort of, like, new technology that you are using these days, or that’s coming in the near future that’s exciting to you or being explored?

HR: So a lot of the preparation work, maybe the hand tools that we use, sorry, the power tools that we use now, are a bit different to what they were 50 years ago. But I think the biggest leap in technology has been that we can now use CAT scans to look inside fossils or look inside rocks to see fossils. Whereas the old way, we basically, if we had a limestone nodule, we would have to acid prepare it to see what was inside. Whereas now we can put it into a CT and we can get a nice, beautiful image of what’s on the inside. And that’s got the advantage as well that it doesn’t destroy soft tissue, so we can get a better picture of what’s going on by using things like that.

Audience question 6: Hello. I’ve been to this beach in the UK, I think it’s called Lyme Regis, where you can walk along and you can find fossilised sharks’ teeth. Those teeth are all black, whereas the teeth that you’ve shown us: not black. Why is that?

HR: It’s because of the sediment that they’ve been preserved in. So when they fall to the seafloor, they get covered in sediment and the fossilisation process actually takes elements from the sediment that it’s in to help with the fossilisation process. So depending on what type of sediment the fossil is in or that the tooth is in, depends on what colour it ends up after it’s been fossilised.

Audience question 7: I just wanted to know, do you have a portable X-ray or ultrasound machines like a gold detector that you can use to find the skeletons?

HR: I wish, but then half the funds gone. The problem is that fossils are very similar, because when they’re fossilised, they’re not bone anymore. They’re pretty much a rock. So it’s really hard to have the technology, there is no technology at the moment where you can scan the ground and differentiate between fossil and rock. We can’t get CT scanners out into the field yet. But yeah, unfortunately, we’ve gotta do things the old-fashioned way with our eyes and digging.

Audience question 8: Actually you probably just answered my question. [laughs] I was just going to ask about, what’s the process of how recent is it bone, and as you go back, how much does it become rock?

HR: There’s not really a fine line between like date or amount of time between not fossil and fossil. There are some mud lobsters that are fossilised up north and they’re done within a million years. Whereas the Thylacoleo, that technically was not fossil, that was just bone and that was 40,000 years old. Yeah, it depends on the environment that something is preserved in as to whether or not it becomes fossil or some fossil or not fossil.

Audience question 9: Has anybody done or doing research on the shark’s teeth from the green sands and the chalk at Gingin?

HR: There’s a little. It’s sort of incorporated into my boss’ research. But the teeth there aren’t very abundant compared to where he’s working on now but he does use those teeth because they’re a similar age. He uses those teeth in his research when he’s looking at the Cardabia teeth.

Q9: Well, will he be publishing that soon? We have an interest in it. Because we actually, when John Long was at the museum, we went up with him and found a new species of shark’s jaw.

HR: Oh!

Q9: And there’s a guy over from the British Museum who saw it and got quite excited and John said, ‘no, you’re not having it.’

HR: [laughs] Yeah, we do that. ‘That’s my turf. You’re not allowed to work on my turf.’ I will look into that for you.

Audience question 10: The question often raised is, is there a dearth of fossils within Western Australia because majority of the land is covered by craters, especially in the Pilbara and down south. So is there a limited area you could really find these fossils?

HR: That is why we don’t have many dinosaur bones in Western Australia. The fossils sites in Western Australia are pretty sparse given the size of the state. The fossil sites we do have tend to be quite diverse, and we do have some pretty specky sites, but yeah, it’s very few and far between. If you look at the size of the state, the whole inside, like, desert part of the state, there’s, you get the cave material. But that’s pretty much as far back as you’ll go.

Audience question 11: Well, I have two things. So first, I remember that, well, when I was a lot younger than this, we went to a beach and there was trilobite fossils all over the place, so you might be interested in that, but I don’t remember where that was. And secondly, what is the picture of?

HR: That picture? I have no idea. It was on the template.

[Audience laughter]

Q11: Oh. [laughs]

HR: I couldn’t change it. I wanted to put a really cool, like, change it from fossil. I probably could have pasted something over the top, but I only just thought of that then. [laughs] Yeah, I have no idea what that is.

Audience question 12: During the presentation, you’ve made several references to sharks’ teeth and also from the other people in the audience. Is it because of the plethora of them because it’s quite surprising. They’re cartilaginous animals so […] is that all that’s left?

HR: Yeah, so the teeth are pretty much the only things that you get and because sharks shed teeth, and their teeth are constantly being replaced, there’s thousands of shark teeth. The only other part of the shark that preserves is the vertebral column, because that can fossilise, so if you find shark vertebrae, then you know that you’ve got where the animal died and usually you can find a whole heap of teeth and that associated with it. But yeah, shark teeth are really common simply because they’re constantly replacing their teeth and they’re constantly being shedded.

Audience question 13: What is your working relationship with the mining companies?

HR: So, my experience has been good. So, like Du Boulay Creek, with the Diprotodon, they partnered up with us and they actually flew us up there. They put us up in accommodation, they supplied us with the logistics to get things back to Perth. So that was a really good relationship. We’re working on another one at the moment, Barrow Island, to get out there. So it’s a bit of a two way thing. We’ve got to give them something and they’ll give us something. But yeah, so far, over the years, my experience with mining companies has been pretty good.

Audience question 14: So that’s for my kids, one of my kids, I’m not saying who, but she really wants to become a palaeontologist. She’s always been interested in that. So she keeps asking, ‘what kind of course should I do? What university?’ Because I’ve looked into it. I cannot find a university with palaeontology degree here. Maybe you can do it another way? Can you tell me your story? I mean how you became a palaeontologist and if you know how to do that now.

HR: Okay, so, I’m actually a bit of a different case. I started at the museum in 2009, and I didn’t actually have a degree back then. I wanted a degree. But I also wanted to work in paleo, and I got the job because it was the mining boom and all of the geology people were off on six figure incomes, and nobody wanted this $50,000 a year job. So I got it. It’s changed since then, so you do sort of need to have that scientific background now to get the job. So fortunately I started then. But I did recently get a degree. In WA, you’ve got UWA and you’ve got Curtin, and they both offer geology degrees, which is a really good background to have to go into palaeontology. So you typically get a geology degree and then you do your Honours and PhD in palaeontology. And Curtin University has a really good postgrad palaeontology lab and they’ve got a lot of paleo Honours and PhD students there.

The other way to do it as well is, I went to the University of New England, which is actually in New South Wales, but I studied from Perth. They’re an online university, and they’ve actually got a really good geoscience degree with a major in palaeontology, and their palaeontology units are really, really good. So I might be biased, but I would recommend that because you do get that broad range of palaeontology experience in your undergrad, which you can then apply to your postgrad. But typically, to be a palaeontologist, you need to have the PhD in palaeontology. Does that answer your question? Yep?

Facilitator: Okay. Well, thanks very much, Helen, and thanks for all of your questions. Such a great diversity and insights into your work, Helen. Let’s put a round of applause together for Helen one last time.

[Audience applause]

[Recording] Thanks for listening to the Talks Archive brought to you by the Western Australian Museum Boola Bardip. To listen to other episodes, go to visit.museum.wa.gov.au/episodes/conversation where you can hear a range of talks and conversations. The Talks Archive is recorded on Whadjuk Nyoongar Boodjar. The Western Australian Museum acknowledges and respects the traditional owners of their ancestral lands, waters and skies.

More Episodes

Gender-related violence isn’t talked about often enough, but it happens in WA. Often, conversations centre on victims and perpetrators, warning signs and cycles, breaking points and crises. But what happens next? How do we move toward recovery, reconciliation, and positive change?

We know ferns have existed on Earth for millions of years, but just how closely do ancient ferns resemble modern ones?

By drawing on First Nations knowledge systems, cultural practices, and research methods, this presentation will showcase how climate adaptation and mitigation strategies that respect and integrate Indigenous knowledges and practices can help sustain well being.

Hear from Dr Amanda Ash from Murdoch University’s School of Medical, Molecular and Forensic Sciences as she delves into the complexity of parasites and their importance.

Join us for a journey into the ancient world with Dr José Galán, a renowned Spanish Egyptologist and director of the Djehuty Project.

Curious about the creators behind our Megalodon head in the Wild Life gallery? Join the makers from CDM: Studio and peek behind the scenes as they share their process of designing, building and delivering museum exhibits.

Discover what we can observe about the Moon, learn about our current knowledge, and understand the importance of returning to its surface!

Discover the elusive Night Parrot at WA Museum Boola Bardip! Join us for an exclusive panel discussion with experts Penny Olsen, Allan Burbidge and Rob Davis.

Join Museum experts Jake Newman-Martin and Linette Umbrello as they take us on a mammalian adventure of the minute kind, from tiny marsupials to giant megafauna.

Discover the remarkable story of Wayne Bergmann, a Nyikina man and Kimberley leader who has dedicated his life to his community, in this moving memoir of living between two cultures.

Celebrate Perth Design Week with a robust panel discussion focusing on design and business.

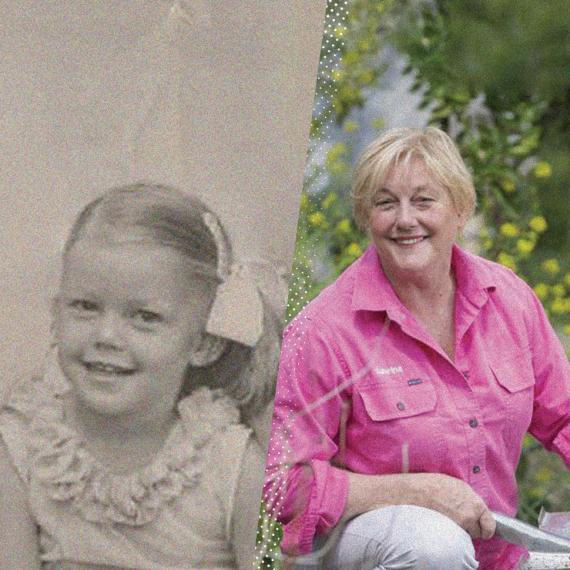

Talk series hosted by Geoff Hutchison that explores who our young selves were and what became of them. This week hear from Sabrina Hahn.

Navigating the delicate balance between the preservation of the Conservation Estate and our cherished and loyal feline companions is both a challenge and a responsibility.

How much will we look to the language of activism in finding the way towards reconciliation in Australia?