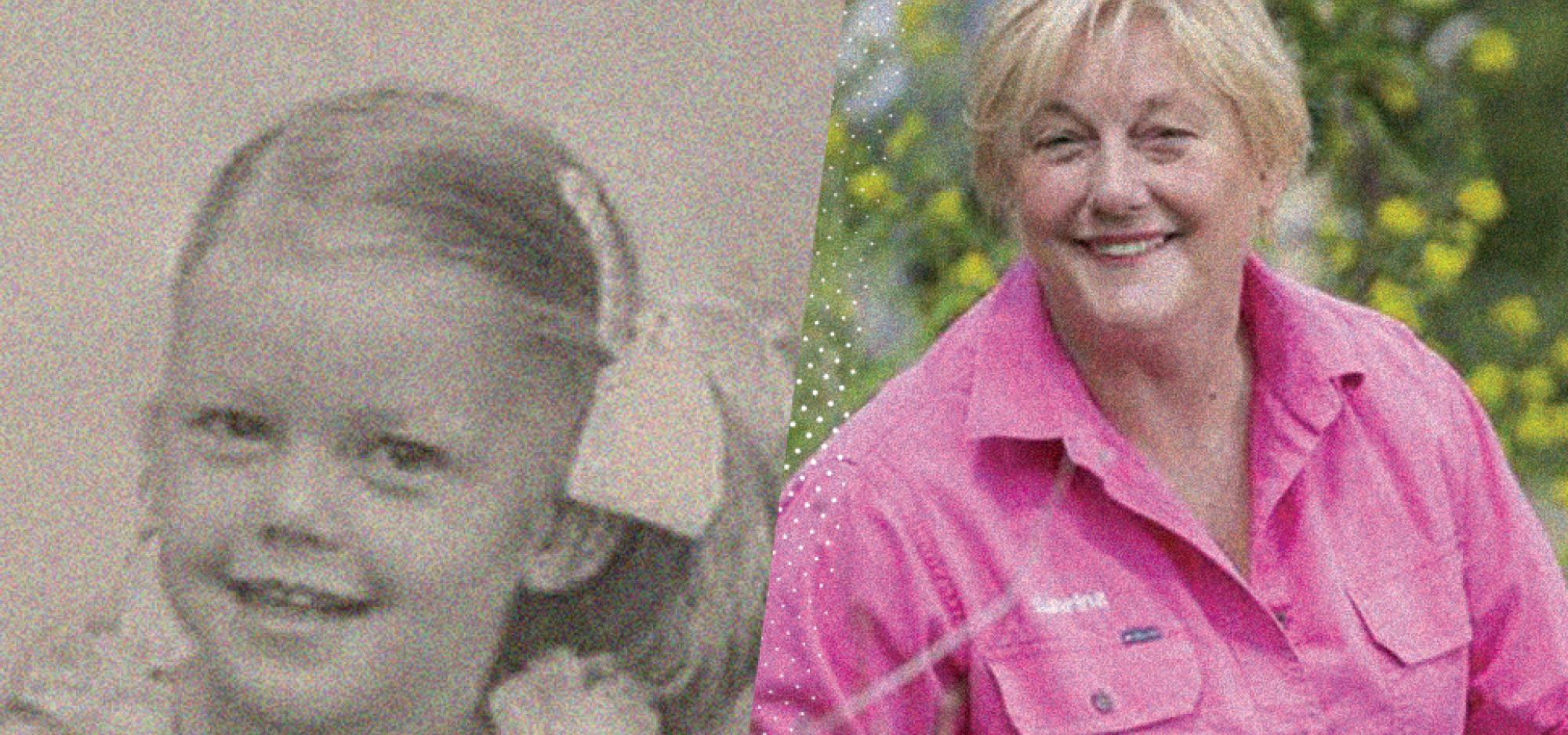

Everyone was a kid, once: Sabrina Hahn

Everyone was a kid, once. It's time to explore the lessons from our childhood.

Who were you as a kid? What was your life like? What did you dream and hope for? What came true and what did not? And what did you learn along the way?

A three-part public conversation hosted by Geoff Hutchison that explores who our young selves were and what became of them.

The final conversation is with Sabrina Hahn.

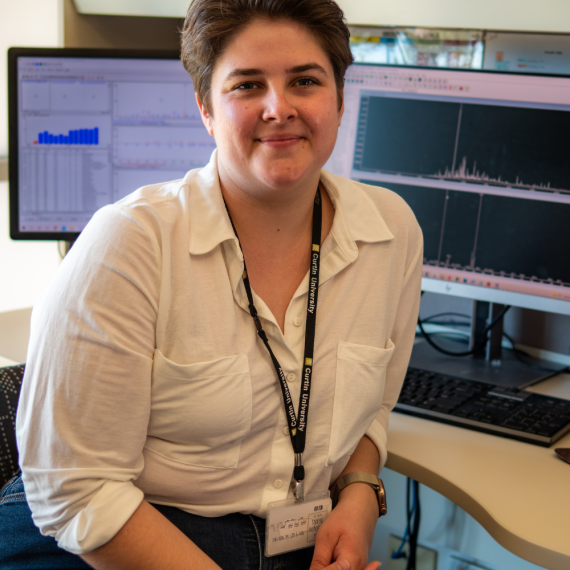

Meet Sabrina Hahn

Sabrina Hahn is an award-winning horticulturalist, garden journalist and designer with a passion for the creation of sustainable environments that bring nature back into people’s lives. Her mantra is to encourage others to take on a caretaker role within their backyards so that future generations develop a love of the natural world.

An obsessive gardener, she started landscaping at the age of four: stripping flowers and foliage from her grandmother’s yard, creating magical miniature gardens all in her Nan’s baking trays.

But Sabrina’s childhood was a difficult one – it’s a story she tells with incredible humour and of course, that famous laugh.

Meet your host

Geoff Hutchison has been a familiar voice on Perth radio for many years as the host of the ABC Morning Programme and then Drive Show. Before that, he was the ABC’s Europe correspondent and a reporter on the 7.30 Report.

Over that time, he interviewed the good and the great; the famous and the infamous – but his real love was always the curious conversation that explored what lay behind the public face. What inspired a person and what underpinned who they are today?

Since his retirement from the national broadcaster Geoff has been keen to take more intimate conversations into the public space. His upcoming three-part series “Everyone was a kid, once.” at WA Museum Boola Bardip promises to be a memorable event.

You are going to be fascinated by his guests.

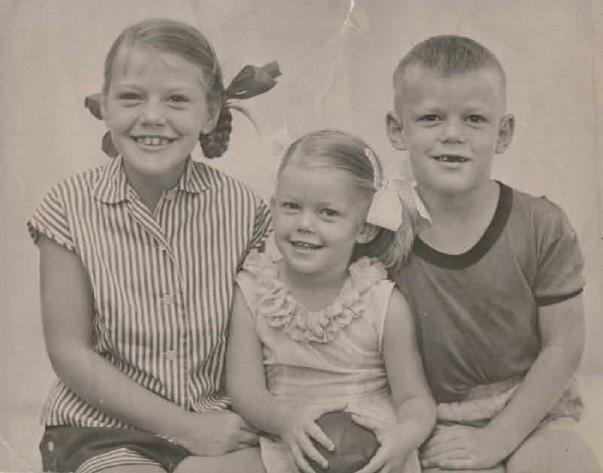

Image: Sabrina sits between her older brother and sister.

-

Episode transcript

Welcome to the Western Australian Museum Boola Bardip Talks Archive. The WA Museum Boola Bardip hosts a series of thought provoking talks and conversations, tackling big issues, questions and ideas and is delighted to be able to share these with you through the Talks Archive. The Talks Archive is recorded on Whadjuk Noongar Boodja. The Western Australian Museum acknowledges and respects the traditional owners of their ancestral lands, waters and skies.

GH: I’d like to begin by acknowledging the traditional owners of the land on which we meet today, the Whadjuk Noogar people and pay our respects to their elders past and present. I wonder how many of you have been generous enough to turn up to the first two of these? A little show of hands? Thank you very much. That's, that's wonderful. And they've been very different experiences. The first was with Professor Fiona Stanley, who is an absolutely marvelous, high achieving Australian and an incredibly good storyteller.

And then we had Glenda Kickett and Glenda enjoyed a remarkably challenging childhood where she was fostered into a white family. She battled overt racism for much of her young life and yet became such an incredible community leader and showed enormous resilience in the telling of her story too. I think the thing that I've loved about this and would like to continue to pursue with them is I think their stories resonate with us because they are memories of your childhood too. And I keep getting back to that sort of question of what were you like as a kid and what did you dream and hope for? And did some of those dreams come true? And because this is the final show, if we have a few moments at the end, I might just ask for some little observations about how different you are to the kid in the first photo you ever had. The very few photos of me as a kid, again I don't want your sympathy, but I do it. And did I tell you that I’ve probably still got a bit of covid. (laughter) My parents obviously had a camera for the two older children, and then in 1963 they ran out of film and clearly my older siblings said, they don't make film anymore, don't take any photos of him. So I thought I was adopted for a while. But then I then I started to show some very familiar Hutchison traits which are not always attractive, but they do link me with the Hutchison's. Tonight I want to, well let's barely introduce you. I want you to meet again, I think, someone you know very well. Her name is Sabrina Hahn. She is a gardener, she is an author, she is a radio broadcaster and she is a philosopher. She might not think that, but I certainly do. Would you please welcome Sabrina Hahn? (applause) See what I mean? Completely untroubled.

SH: Wow, there's a few people here Geoffrey.

GH: I know. And ladies and gentlemen, I might say that tonight's conversation is not for the faint of heart. It contains dramatic scenes that you will find almost beyond belief. It also includes many useful tips on how to kill parents.(laughter) Isn’t it funny that they find that an amusing idea.

SH: They’ve probably all had a go.

GH: Quick show of hands if you’ve tried to kill a parent and got away with it scott free. How many of you would have tried this? Hands up.

SH: Yeah, it's a few.

GH: Yeah. So to the tall young man down the back, keep your hand down.

SH: He looks remarkably familiar to you actually Geoffrey.

GH: It's, crazily enough, it's not about him tonight. Now, hello Hugh I'm very glad you're here. Can we begin with this beautiful photo?

SH: Yes

GH: That's you in the middle.

SH: Yep.

GH: And on either side is who

SH: So, Bucky, my older sister, she's the oldest. She's called Bucky because the next brother down couldn't say J, couldn't say Jackie. So he called her Bucky, and it stuck for her whole life long. And on the other side is my brother, Rod. So there's two years between all of us.

GH: Okay? And you're the older three of a total of five?

SH: Yes. So there’s two younger brothers, eight and ten years.

GH: What do you see when you see that kid in the middle?

SH: I see a really cheeky, happy little girl that obviously can get away with blue murder or in our case, red murder. I look a bit mischievous, don't you think?

GH: Yeah, I think so. You told me the other day that you could find joy in the smallest of things. What kind of things?

SH: Well, I was very little. And even though I was the smallest of three, I think my mother smoked more with me than the other two. So I was always I always felt little and I was always crawling around the ground. So I loved flowers. I loved flowers, I loved beetles. I loved eating dirt. I loved all the little things that I could see. So I had enormous joy just going outside and playing with anything that was there.

SH: And clearly, you know.

SH: Still do.

GH: Not much has changed. I understand you had three fairy friends.

SH: Yes.

GH: When you were growing up.

SH: Yes. So the three fairies lived in the grape vine at the back, the back verandah was all covered in in grapes. And I refused to eat unless there was a setting for the fairies. They had to sit with me and they had a great liking for Milo and cake.

GH: Yeah.

SH: So they were quite demanding really Geoff.

GH: Yeah. Not so much brussel sprouts, they didn’t want those.

SH: No, they didn't like brussel sprouts at all.

GH: It's a bit of a sidebar question, but did your fairy friends fly away? Did you stop thinking about them? When did they leave?

SH: Yes, they left when I would have been about, I reckon, eight years old. They just didn't come around anymore.

GH: Have you ever thought about them in the intervening years?

SH: I still believe in fairies.

GH: Ladies and gentlemen, our three fairies are in the audience tonight. Please, you should have noticed. Do you think about them still?

SH: Yeah, absolutely. I'm so pleased they were part of my life because they used to tell me to do naughty things as well.

GH: Did they?

SH: Yeah they did. So I used to make kingdoms for them.

GH: Kingdoms?

SH: Yes. So I would borrow my nan's baking trays and cake tins, and then I'd go and collect all sorts of little beetles and things for them to play with. And then I'd make different kingdoms out of pots, pans, baking trays, cake tins. All the things that probably people wanted to cook with later on in that day. And then I'd take the kingdom to a place and then the fairies would tell me, You have to cut a big hole in that, or you have to cut those branches off and make a teepee.

GH: Yeah.

SH: Or you have to go and pick all the apricots and put them in a bin for us so we can eat them later.

GH: Yeah.

SH: They didn't tell me that I'd get diarrhea as well.

GH: Yeah.

SH: So the fairies were great. They were very instructional for actually landscaping later on in life.

GH: Your early life, until the age of about five, was spent in Papua New Guinea. Why Papua New Guinea?

SH: Okay. So my father, Kevin Han, he was like all the Australian, he was in the Second World War. And like all the many of the Australian troops at the end, towards the end of the Second World War, when the Japanese were invading, the men were all pulled back to Papua New Guinea. So he spent a year there and he was very he was so grateful and thankful to the Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels that helped the Australian troops while they were there. So he was shot, he was injured, they helped carry him out. He went into villages where he saw what happened to the people that lived in the village when the Japanese came through. And he felt that because the Fuzzy Wuzzy’s helped them so much, he wanted to go back after the war and repay a debt back to say thank you.

GH: He was an engineer or surveyor.

SH: He was a surveyor during the war. And then he studied engineering after the war. So he was part of the rebuilding of Papua New Guinea when they got their independence.

GH: Okay. So your earliest childhood memory is what?

SH: Oh, terrifying. Um, I don't know where we were, but my father took us to a village, and my very earliest memory was at a Sing Sing. So they had a witchdoctor. So I remember being between my father's legs looking up at this man who literally had a bone through his nose, right. And stuff all over his head. And it was terrifying. And then there was just the sound of feet and dust. And because I was low to the ground, I remember the feet and the dust. But this witchdoctor was the most horrifying thing I'd ever seen in my entire life.

GH: Yeah.

SH: So you can understand why they, you know, they bring them out when they have their battles and things. Because I know I'd run.

GH: Scared a five year old witless. Can we have a little thumb sketch of Dad and Mum? Kevin and Jocelyn?

SH: Yep. So Kevin Harm came from a poor family. His father came over from. He was German, he was a baker, came over from Germany. Married an Irish girl who was sent out on the ships. And they were, she was married via mail. So they settled in New South Wales and...

GH: What kind of a fella was your Dad?

SH: He was a really, so they were very poor families. So he was one of seven and five survived. He was a real egalitarian and I can see why he went back to New Guinea because I guess they were from a poor family and dad believed that everyone is equal and that everyone should be given a fair go. And he loved the bush, he was a great bushman. And he had this, he was very musical, actually. And loved theater. I wonder where I get it from?

GH: Yeah, there's another part to that story we'll be telling in a few moments anyway.

SH: And he would you know during the war he was always part of the troupe that sang and got dressed up and danced and when during my childhood dad would be in the repertory theater, singing and dressing up and being silly and so he had a deep love of nature.

GH: Tell me about Jocelyn, because I think just some came from another world, didn't she?

SH: She came from a very wealthy family. Yeah. So my mother and her sister and brother, they were sent to boarding schools overseas. So she spoke. She was very intelligent, very well-educated, spent most of her life in Europe, and then came back to Australia when the war broke out. And her mother, Jessie, Hope Stuart, she had the most wonderful life, because she just shoved the kids off into boarding school and off she went and did tremendous things.

So Mum grew up with a sense of I can have whatever I want basically. But well-educated, spoke fluent French and Italian.

GH: What was it like when she came back here after a European education as a young girl?

SH: Boring as bat shit, I would have to say. She, so she was engaged to an airman who was of her social standing and he was killed during the war. So I think she had expectations that she would be of high society and, you know, mix in all those circles that she was used to mixing in.

GH: Yeah, your dad was married before.

SH: He didn't have a lot of luck with women. He would have been better if he'd gone on Tinder, I think Geoff. So he was married. His first wife nicked off with an American airman and he's never liked Americans.

GH: So before they married, your mum had been engaged to an airman?

SH: Yep.

GH: Who died. Your dad was married to a woman who ran off with an air man.

SH: Yep.

GH: It wasn't the same image.

SH: No, it's like a soap opera, isn't it really?

GH: Yeah, it is. Sabrina, is it distasteful of me to suggest they might have given what you've told me about their backgrounds and who they are, did they met on the rebound a bit?

SH: A bit? I reckon this is how it would have worked. They would have been a ball on somewhere. And I reckon that Dad would have got a few drinks under his belt because he was a bit older than mum. So he was ten years older than Mum, but he had an absolute, you know, that laconic Australian charm and I think she probably thought that that was, you know, something exceptional. She wasn't up the duff so they didn't have to get married and she would have, she was stunning. She was six foot, she was a model, very attractive and I guess Dad just swept her off her feet for one night.

GH: Yeah.

SH: And yeah, so it would have been a rebound for sure.

GH: Because did they want the same things? It doesn't sound like they, they didn't come from the same place. So did ?hey want the same things.

SH: They definitely wanted the same amount of alcohol. That was, that was, they could go drink for drink, no worries.

GH: If they had a shared talent, it was their ability to consume alcohol.

SH: Definitely. They were on their equal run. They both would have got a ribbon for first at the end.

GH: Is it a bit like the sitcom Green Acres where Zsa Zsa Gabor gets taken to the country and says it's not like Manhattan? It sounds a bit like that to me, only it's not funny.

SH: Yeah, thats exactly right.

GH: It's actually a pretty black comedy story this right?

SH: It is. So she was happy in New Guinea, though. Because in New Guinea she had servants, many servants and it was a wild place, you know. So it was exciting for her. And there were there weren't very many white Australians there. So and because she was well-educated, I think she felt like she was sort of the queen bee.

GH:Yeah.

SH: And dad loved it, like Dad would just go out bush. So she had servants to do whatever her bidding was. And I think Papua New Guinea in those days would have been a really exciting place.

GH: You moved around a lot, just give us the scope of the family travels.

SH: So we went from New Guinea to just north of Cairns and I think that's when, because Dad always worked on new projects so there wasn't a lot there. So the town, so we started off in Cairns and the three of us, we all got expelled from primary school at a very young age.

GH: For?

SH: Well, I don't think we fitted in because we all spoke pidgin English and I refused to put clothes on. I just used to take my clothes off all the time.

GH: Yeah.

SH: And I couldn't understand where all the white people came from. So I just followed black people because that's what you could do. You just go oh, I’ll go off with them. So I think Mum was really deeply unhappy even by then.

GH: Okay.

SH: But the marriage hadn't broken down too much. So my dad took us out on camp. So we, so the three of us went out bush with my dad. I don't know where my mother was at the time, but we spent a lot of time out bush. And the camp cook was our teacher and he used to hit the vanilla essence. So he didn’t care what we did so we just used to bugger off.

GH: Yeah, right.

SH: And I could take all my clothes off, it was great. So we went from Cairns.

GH: Yeah. I do want to talk about the town of Merriwa.

SH: Yes.

GH: In the Upper Hunter Valley, because I sense that this might be the place where things go a little awry.

SH: Things went a bit astray there. It wasn't too bad. We went from Cairns to the Snowy Mountains.

GH: Yeah.

SH: Mum liked it there though, because she could speak Italian and French, because there were a lot of immigrants working on the Snowy Mountains with the scheme. And I think she probably taught them other things as well. But when we got to Merriwa, that's when things really fell to bits.

GH: Yeah. Because you talked about your dad and his love of sort of amateur theater, but your mum quite liked theater as well.

SH: She, she did.

GH: So what happened, if you don't mind me asking?

SH: So my mother would throw caution to the wind when it came to actually keeping her pants on. So she um, I think because my father was older and he didn't have the aspirations that she had for him.

GH: Yes.

SH: So she was unhappy. She got bored. She didn’t work. So she found her joy with other chaps.

GH: Yeah. So she's in a play.

SH: She was in a play. And the person, it was sort of like a bit of a love story, but unfortunately, the person that was part of the love story, who was her..

GH: We can name him. He's not here.

SH: Iva Peebles.

GH: Is there a Iva Peebles in the room?

SH: So he and mum were having an affair. So then it came to the bit on stage where they kissed. But Iva’s wife was in the theater, and then she started screaming, there was attacks on the bloody theater. And then someone came to the door who was going to shoot someone else. And I can't remember whether Iva’s people were going to shoot mum or whether it was his wife that was going to shoot mum. So at midnight we all got dragged out of our house, out of bed and we had to leave town. So I was put in a truck with someone I'd never known before, never seen before. And my dad and Bucky and Rod were in another truck with Mum, crying because the love of her life. But we were basically run out of town.

GH: And it wasn't the only time, was it?

SH: Well, that continued. That just went on and on and on. But without the theater.

GH: It's pretty amazing, isn't it? Because when you and I are talking about it and I'm writing things down and I'm and I'm laughing, and the more you tell me it's still amusing because you are who you are.

SH: Yeah.

GH: That's terrible set of circumstances.

SH: Well, it's not really, it's not really what you teach your children, is it?

GH: Because it became a pattern of your mum's behavior.

SH: Always. Always. So because she was so unhappy, she found joy in other...

GH: Rooting around.

SH: Rooting around, just banging anyone. But, you know, there were times when it wasn't that funny. It was quite confronting.

You know, when...

GH: I do know and I know the question that I ask that will elicit the response from you, and I still don't even want to ask it. Tell me about you as the young high school student coming home?

SH: Well, so we knew that by then Dad just went out bush most of the time. He couldn't cope. This is by the time we got to where I grew up in high school, Ashford. And I came home from school early because we had a sports carnival. And I walked in and there's my mother banging my primary school teacher. Now, that was, I felt really awkward. I'm sure... (laughter)

GH: What a prudish child.

SH: I know that he definitely felt really awkward.

GH: Yeah.

SH: And they weren't playing chess. Like it wasn't that kind of a, wasn't that kind of a thing. GH: Do you remember how you kids processed this time? And I know we're going to get onto another matter in a moment, but how you assessed what was happening in your family life?

SH: I think by this stage that we, because we had to leave, we had to move like every two years because of Mum's behavior. And I think for Dad, it just totally destroyed him. But I think as a kid you just go, Well, we've got no control over any of that. That's how it is. I mean, you know, you could come home and there's someone there. You know that they're not fixing up the stove or your plumbing, or someone's plumbing. So I think you just go and you leave the house like.

GH: Yeah.

SH: We left, you know, we just, the three of us were really good mates, Bucky, Rod and I, and I think if I hadn't had the closeness of siblings, we all would have just been a mess.

00:25:13:06 - 00:25:44:23

Unknown

But we used to talk about it and we had a rating system for the blokes. So we had this, we used to make cubby houses the three of us and we’d have, so Bucky, she would always scribe. So we had a rating system of, cause we didn't know anything about sex, like we knew that we were doing that, but we'd have a rating system of, you know, Did you think he was handsome enough? What do you think he was doing? What sort of clothes were he wearing? Do you think he was a prince from somewhere? Do you think he was the garbage man? So and then we we'd score and rate them.

GH: Yeah.

SH: So that's how we coped.

GH: You’ve got good senses of humor.

SH: We had marvelous senses of humor. Yes. And we had nothing to lose.

GH: Yeah.

SH: So by that stage, we were all.. It was weird.

GH: Was it was a violent home sometimes?

SH: Certainly wasn't a lot of fun all the time. It was extremely violent. So by the time we got to, so Merriwa was the beginning of Dad just not coping. And I actually think that Mum just didn't care any more, so she just wanted to push him, I think, to the limit. I don't know why he didn't leave. So the drinking got heavier. So what happened was all the money went on grog. So it, and then they started fighting really, really badly. Like Dad never ever hit mum, and we used to pray to the fairies that he'd just punch her out one night. And we even, like I said to Rod, you've got to learn boxing skills so you can train Dad, just an uppercut.

GH: Yeah.

SH: So what happened was they would fight with each other, but Mum would get really violent and there would be pots and plates smashing. And this is like 11:00 at night. And then she would just go on a rampage. We'd get dragged out of our bed at 3:00 in the morning. She'd go through, she'd just rip apart the whole bedroom, just rip everything out, screaming and yelling, slam you up against a wall, you know, say she's going to kill you. And then she’d say, all of this has to be cleaned up by the time you get on the bus tomorrow morning. And you wanted to get on the bus tomorrow morning, because when you went to school you were safe. But it was, and it's interesting when you think about violence and how children, lots of children are exposed to violence. It's interesting how you cope with it, because you, you have to in order to cope with that and just carry on, you become a facade of the person you are and you don't, you don't learn things. Or nothing comes in. I remember when I was 15 and someone talked to me about the seasons, and I thought I didn't even know we had seasons because there just...

GH: Just no room.

SH: There was no capacity to process things like seasons. There was madness, insanity, violence, hiding, running away. Seasons were like whatever. It's the same every day in this household.

GH: Yeah.

SH: So you become where you just can't process stuff and I'm sure we all thought we were really dumb because we just didn't have the capacity to go, oh trigonometry, how marvelous.

GH: Yeah, You're not at ease. You haven't got the opportunity to be at ease.

SH: It's walking on eggshells. Yeah, but she was the most violent with my brother.

GH: Now, dear friends in the audience, the next portion of this program is going to focus on the subject of how to best murder parents. It, I cannot be clearer. It is not meant to be a guide. And for some of you, the advice probably comes too late. But it is, it is all true. Sabrina, tell us about the plans of these gorgeous kids.

SH: It was so lovely.

GH: The plans of Bucky, Rich and Sabrina to kill their parents.

SH: Okay, so when conspired for murder, it had to be down in the woodshed because no one must know about it. So the three of us would go down the woodshed and my sister would scribe. And I had seen a play where they used hemlock, which was apparently very difficult to find on the body. But as my sister pointed out, we didn't have any hemlock. So then the next thing we thought was rat poison or mouse poison. So we wondered how we could actually put it in, the first thing was put it in their drink. But we figured that they might actually, they might taste that.

GH: Yeah.

SH: So then we thought we'd have to grate it and put it inside pastry or pies or something like that.

GH: Yeah.

SH: But it, and we mixed it in with mud and water and it actually had quite a color to it so we thought they might actually see the color.

GH: A lot of people nodding their head. (laughter)

SH: We thought of putting all sorts of stuff in their drinks?

GH: Strychnine?

SH: Strychnine. We thought of strychnine. And the other thing that we thought of was trying to drown, we didn't mind if we just killed one at a time. Bit hard killing both.

GH: Yeah. Now this, you told me this the other day and I thought this was, this shows how cunning they were. You said you thought there needed to be two different plans because if you had the one plan and killed both parents it would look suspicious.

SH: It would look very suspicious.

GH: Yeah.

SH: And the other thing we thought of, if we killed them together, we had to get rid of two bodies simultaneously.

GH: And that became complicated when you were talking about the potential of perhaps drowning them.

SH: Yes. So we had cats and when they had kittens my father used to drown the kittens in a bucket. So I said to Rod, you'd be strong enough, Bucky can hold her, you push her head down and I'll hold the bucket. But as he said, she's pretty strong.

GH: She's strong and..

SH: And we had to hold her in for a significant amount of time.

GH: Today we'd probably use a big wheelie bin, but they didn't have them back did they? SH: We could be Snowtown and actually cut them up as well.

GH: So

SH: But see we didn't have rubbish pick up.

GH: So a bucket was too small.

SH: No, but the other thing that did cross our memory, we had um, so we didn't have septic pits, we had raised septic tanks because of the clay, but it had a lid on it and the thing where they came and drained it. So we thought we could shove them, one of them, preferably mum down there, but it was too small. We measured the hole.

GH: Mum. What is darling? Can you come out here to the septic please? Why? Could you just come out here, please?

SH: But she wouldn't have fitted down the hole. Dad was pretty skinny, he may have.

GH: Yeah.

SH: But we had to get rid of her first.

GH: Venomous snakes.

GH: Yeah, that was the other thing. Because Dad loved the bush, so we didn't want Dad to die in a sewerage pit. So we knew Dad loved snakes spiders, and so did I. And I used to actually collect snakes and spiders and bring them home. And then my father would take me back. Take, I had to take them back where they came from. So we thought when they got really smashed we could lock the door, just let venomous snakes because I had all the King Browns and things and, and, and redback spiders and funnel webs. Just let them all go in the room and he'd be quite happy to be killed by snake.

GH: Did you, did you actually go ahead with this Vaseline on the steps?

SH: Yes.

GH: When they came home drunk?

SH: That was hilarious. So, Mom used to come home and everything would be ripped out of the cupboard and slammed and smashed and thrown against walls. And cause you never got any sleep when that was going on? So I said to Rod, what we need to do is just glue everything down. So we got araldite. We glued all the pots down and I glued a whole set of plates together. So it was worth the thrashing. It was so funny. So, so what we did was we put that, beacause they were steep steps, they would have been from the, from the back the steps come up about this high. So they're six steps with one railing. So we smear it, because it was pouring with rain, and we knew that came home about 1130, somewhere around there. So we smeared the edges of every step thick with Vaseline and also the, the railing. Anyway, we heard them coming in because they were fighting. And then one of them hit the decks. I, I, I, well, I don't know which one it was. And then it was all fighting and carrying on. And then the cupboards were open and then you all you heard was expletives coming out. Cause she obviously went to get stuff and couldn't get it out.

GH: She's funny isn't she, the gardening lady. Some of you know that she came from a background a bit like this, but are most of you hearing some things tonight that you didn't think you would hear? Perhaps in a lifetime? Perhaps about anyone?

SH: I think that was our most ingenious.

GH: But you just said it was so funny.

SH: It was hilarious. We were killing ourselves. We knew that we'd get absolutely belted, but it was so worth it.

GH: Um...There's another way that you have to look at these circumstances. And as we absorb the jokes, and they’re hilarious, and the prayers for bolts of lightning, please God, kill them. But it must have been really frightening.

SH: It was terrifying. You lived in fear constantly. You were on the edge of fear, and the worst part was sometimes they were quite normal. Like mum was sometimes quite normal.

GH: A good day was a good day.

SH: A good day was a great day. But you may not get that tomorrow. And we never knew what triggered it, but certainly when they drank it was danger territory.

And you know, my oldest sister Bucky feed us, did the washing because they were never there. And there were times when there was no food and I remember Bucky putting red food coloring in the water because all we had for dinner was a Weet-Bix each, which we thought was pretty poor. We thought she could have done a much better job than that. Personally. So, but you know, with things like that, when it comes to food, we always seemed hungry. But because the three of us were together, it was, we coped because at the end of, you know, in our little moments in the office, the woodshed, we would talk about everything, everything that happened, and we would process it that way. But we'd laugh, because we

GH: And whatever was happening was happening to the three of you. And you were the tightest little group.

SH: Absolutely. Tight, as tight as tight.

GH: Your dad didn't make old bones did he?

SH: No, so my dad died when I was 19. I never, I didn't go home for the funeral. He died, well he was not the healthiest of chaps, so he had cirrhosis of the liver. He had ulcers, his heart was buggered. And he was very unhealthy, like always looked really unhealthy.

GH: Do you reflect on him and think, because I can feel a fondness towards your dad. Do you think life could have been quite different for him if Jocelyn hadn't been?

SH: That's why it was important to murder her first, because we'd give Dad a bit of a second go. Um, oh definitely. They were so mismatched and destroyed each other and in the process destroyed, well they didn't destroy us, but made life very difficult.

GH: I'm really interested, though, that when the three of you had your chance to get out, you got out really quickly. Where did you go? What did you do?

SH: All of us got out the minute could. We left home. So I finished my last exam. I hitchhiked down to Melbourne, got on the boat across to Tasmania and did the Cradle Mountain Lake St Clair walk. So I just hit nature. I just had to not be with anyone, talk to anyone, do anything. I just had to be alone on a mountain. My brother ran away from home at 16 and lived on the streets in Sydney for two years and the Salvation Army saved him.

My sister left home as soon as she finished high school and married the first man that was kind to her. He turned out to be dickhead. So we all...

GH: That's what people do though, isn't it?

SH: Yes, absolutely.

GH: The first time that is an expression of kindness

SH: and security. We all wanted to feel secure somewhere and we would all kill for each other. It’s ok, I like you people here? But I was, by the time I was 13, I could have been a child murderer because my mother stabbed my brother. So she was pretty, she was pretty happy with knives and razorblades. So she went to stab his throat and he went like that. And so it severed his thumb. So I walked him up to the hospital and they stitched all his thumb up. We were often up with injuries. No one ever asked anything. No one ever. There was never a word. So that was enough for me. I thought, she will kill us all. But kill me before my brother, because he takes so many beatings, because he used to get walloped by dad as well. And I was so, I was so fearful that I would lose my brother and my sister. I thought, I have to kill her. I have to do it. I'm the youngest. They probably won't put me in jail, but something has to happen. I can't do this anymore. So I actually went and got a hammer and I stood over my drunk mother at midnight looking at the hammer, and I thought I could just smash her head and it's all over. That's a pretty out there thing.

GH: Do you know why you didn’t?

SH: I don’t know why I didn’t.

GH: Kind of glad you didn't.

SH: Well, I don't think I could have gone through with it anyway. I mean, that's quite a violent thing.

GH: It is quite a violent thing.

SH: And I don't think I could of, I probably would have gone trembling. And she’d go, What are you doing? and then I would have just run to the woodshed.

GH: We had a chook named Blackie when I was a little kid and there was something wrong with Blackie and Dad had to go and chop Blackies head off. And I said, I'll do it Dad. Why don't you leave it to me? And he goes, Okay. And he gave me the ax. And he said, There's Blackie. And I think about a minute and a half later I was weeping. Please don't kill Blackie Dad. I'm really glad you didn't kill your mother.

SH: I am too.

GH: And I know that there are other encounters with her as you got older. But I want to talk about something that you first spoke to me about many years ago in the context of your family. And you said to me one day, and I just think I think was a such a beautiful thing to say, I feel like I've carried it with me since. And it's just a wonderful message. I asked you how you got through some of these experiences or how you reflect on them. And you said they just taught us resilience.

SH: Absolutely. People think adversity is a bad thing. I totally disagree. I think adversity actually molds who you become and you never build up like I am strong. I stand up for what I believe in. I have, I feel that I have a life force that has been forged from fear, hatred, anger and turned it into something beautiful. So, (applause)

GH: Now that is the first part of a fantastic answer. And the second part has to be how do you do that stuff? How do you turn such negatives? I mean, you speak of those things, those emotions. I have turned this, this and this into something beautiful. How do you how do you do it? Where do you summon?

SH: Well, it's not easy and it takes a fair while. So the first thing you have to do is understand that you no control over any of those things that happened to you.

GH: This wasn't your fault.

SH: It was not my fault. It's not my brother and sisters fault. We had no control over that situation. But the minute I got on that mountain, I said to myself, I have complete control over my life. They have no control over my life anymore. I have control. I will never, ever let anyone ever hit me again. I will find joy somewhere. And I knew I had to go to nature because I love nature, but I had to be alone to do it. I don't know why, I had to be alone in nature, because nature cuddles you, nature envelops you. And you know, I was always little as a little girl, but in nature, all the little things are the most important things. And, you know, when I studied I discovered that it's the little tiny things that are the drivers of the ecological wheel.

So going into nature, going into mountains where I didn't have to speak to anyone. Well, remember I told you, I pretended that I was deaf and couldn't speak?

GH: Yeah. That little imagination of yours really took you to some places didn’t it?

SH: Didn’t it ever. I could talk to the fairies of course. But when I was nine, I had an epiphany. My parents for some unknown reason gave me a Bible at nine. I've still got it. And they engraved in it, Happy 9th Birthday. And I remember thinking, There's certainly no bloody God in this household. Um and I went to bed that week thinking about the Bible and everything that Christians are supposed to do and that was during the famine in Africa, so there was lots of vision of that. And I lay in bed and I thought about all the other children that suffer. So I thought about all the children in Africa that suffer, that are much hungrier than we are, and I am at the moment. And I thought those children that are suffering are lying down, thinking the same thing about all the other children that are suffering. And we are all together, all of us children all around the world. We are all linked together. We are not alone. We are together.

GH: Wow we.

SH: And that was at nine.

GH: And you still believe it?

SH: I still believe it. I still believe it. It's, it's, and I've got fairies as well, which is always helpful.

GH: Did you, because you talk about going into nature and being by yourself, was that just a period where, yes, you did pretend to be deaf and other such things, but did you not did you not want to be around other people? Did you not have faith yet in other people?

SH: No, I hated people. I wrote my own Bible where the first rule was I'd never grow up to be an adult. The second one, I would never have children. Well, there were two parts I'd never marry and I'd never have children. Failed on the second one. I'm so pleased I did have children. I keep telling them I’m a marvelous mother. That I would always, my father instilled in us to be humble. So that was the third decree. I would always be humble and never put myself higher than other people. And I would always leave a little bit of food on my plate for the fairies.

GH: I am.

SH: I still do.

GH: Do you?

SH: Yeah.

GH: I'm imagining, in a way a life in nature and a deep understanding of life and great curiosity about life. But I can sense an introspective version of you. How did you become the version of you that we know?

SH: I met wonderful people. So I just traveled for a while, and on my travels I met beautiful, I had no idea so many beautiful people were in the world. It was fabulous. And I got boyfriends and it was just like, Wow, there's a whole pile of people out here who are divinely gorgeous and generous and giving and funny and happy. And it still took a little while. You know, a couple of years. And then I thought, you know, life’s pretty good, I might talk to this one.

GH: Yeah.

SH: Pretend I'm not deaf.

GH: Yeah, yeah. I mean, I'm not saying that would have made any difference, but.

SH: Yeah, yeah, I just what happens is when you go through all that stuff and when you try and find out who you are, I was never, ever suicidal, by the way. Never, ever suicidal. I had no fear of anything because for me, it didn't matter if I died, but I was never suicidal. Because I would never give that to my parents, that they forced me to do that. But I just, I think when you go out into the world and you start sorting yourself a bit, which I had to do in isolation, you let go of stuff, you just go my childhood, everything that's happened, you never, ever get rid of it, ever. There is no there's no reconciliation to that.

GH: Yeah.

SH: But what you do is you have to open up to let all the ooze out and allow light to come in. So it's that letting go. It's not, it's not that it will never be there, but you have to let that stuff go because you can't bring all the really beautiful stuff in. And I am so blessed because I know I'm very loved by more than just my siblings.

GH: Yeah.

SH: And I, that is the best blessing of anything. So I have been repaid back, a gazillion times more.

SH: When did you last see your mum?

SH: So we all went over, she had leukemia, so she was 72 when she died. So my sister rang me and said Mum's got leukemia and she's been given six weeks. Cause once I left home on it went back. She's been given six weeks to live and I went good luck leukemia, that'll never knock her off. So she said, You need to come over. And I said, I'm not because she won't die. It'll, the leukemia will run away screaming. And then she rang me four weeks and she said, I'm going to send you the doctor's report. And I thought (grumble noise). So I went across because I thought, I wonder if she'll ever bloody apologize. And then when I got there, I realized that she wouldn't because she doesn't believe that she did any of that stuff, I'm sure. But when I got there, she was weak, she was sick, she was in pain and she was just this old lady that was highly vulnerable, lying in bed.

And I just went, It's over. It's, I don't need to say anything, do anything. I don't need reconciliation. And I will stay because my sister really wanted to stay with her. So I said to Bucky, I will stay with her and we will make sure that she dies.

GH: Because she still had a few tricks up her sleeve did Sabrina. If required.

SH: She'd be easy to drown in a bucket at that stage I reckon, I could have just taken the oxygen off her. So we looked after her in hospital for four weeks. My God, I have never laughed so much in my entire life. So my sister and I, it was like a party every day. And I took in champagne, because she ruined my 50th birthday because she died on my 50th birthday. So I had to cancel the party. So I thought stuff you Jocelyn. I'm going to come in with a bottle of champagne. All the nurse came in. I went and got another two bottles of champagne and we drank. I said to them, I said Mum, have a glass of champagne. Oh you can't.

GH: Wow.

SH: And of course she died. So she died anyway, as she's dying, apparently people do this. So we're all going, is she gone yet? Is she gone yet? And I’m going, I hope. No, still alive. And then she, we thought she died when she (gasping sound) and I and I said to my sister that’s it, I'm on the next plane home, she won’t bloody die.

GH: But she did.

SH: And she did.

GH: And that was it.

SH: That was it. She died and it was, well, she died. But I didn't feel any, yeah, no remorse. I didn't feel

GH: Anger.

SH: Anger. There was no anger at all. I went, well there you go.

GH: There you go. Yeah.

SH: A life not well spent. But then of course we had to organize things, Jeffrey, when people die.

GH: Yeah. Did you leave you a wonderful legacy?

SH: Yeah, she left her mobile phone bill and a credit card bill. But, so, we rang all the others. They were a bit late coming. And then the undertaker came in and he said, you know, what would you like to do with your mother's body? And we went burn her. And they said, oh a cremation. Would you like to come, would you like to come and look at the, you know, the boxes and stuff? So I said, have you got one that you can run through the furnace twice? I just want to make sure...

GH: Truly, ruly?

SH: Truly, ruly. But my brother was there and he was horrified. But the look on the undertaker, he was like (laughter) We didn't run her through twice we only went through once. Probably would have cost more putting her through twice.

GH: We’ve only got a couple of moments left. But can you just look at that little kid in the middle? What do you see?

SH: I see a really happy, mischievous little girl that loves life. And the most beautiful thing about that photo is, I haven't looked at it for years, is that’s who I am now.

GH: Ladies and gentlemen, We're all kids, once. Lessons from childhood. Could you please thank the extraordinary Sabrina Hahn. Now, of course, Sabrina will be back here during the Perth Festival next year to do the unedited version of her life story. If you thought tonight was fruity, you wait till she really gets into it. And in fact, I think from the several occasions that you and I have discussed this, each time I'm hearing things tonight that I've never heard before, and I just can't help thinking that the more we talk about, the more you might say things like, should I have gone to jail for that?

It's a beautiful story in that you are able to tell it.

SH: Absolutely

GH: And that you are, everyone knows you as this gregarious, gorgeous, life affirming human being. But you come from a really challenging circumstance and I think some of your life lessons are ones that we can wander off with tonight. It doesn't matter how old you are. There's, there's great value in them.

SH: I hope all the older people here can have nightmares about their children murdering them all. Do you know, the whole family are very well-adjusted, which is surprising. So my sister, Bucky, so we all went to university. We all got degrees. My sister Bucky, now lives at Secret Harbor, and we're still. My brother lives in Sydney, and I fly over to see him four times a year. We and my two younger brothers, even though there's a big gap, we are the five of us. Particularly the first three, are so tight. We are, have been our whole lives long.

GH: Ladies and Gentlemen, Sabrina Hahn.

SH: Thank you.

GH: It depends on your enthusiasm for the idea and whether you think you'd like to come along again. So we'll see how we go, but thank you. This is the first kind of thing I've done in a non radio world since I left radio. And it's been really thoroughly enjoyable and absolutely wonderful that so many of you have come out on so many nights. Thank you very much indeed.

SH: Thank you.

Thanks for listening to the talks archive brought to you by the Western Australian Museum, Boola Bardip. To listen to other episodes, go to visit.museum.wa.gov.au/episodes/conversation where you can hear a range of talks and conversations. The Talks Archive is recorded on Whadjuk Noongar Boodja. The Western Australian Museum acknowledges and respects the traditional owners of their ancestral lands, waters and skies.

More Episodes

Gender-related violence isn’t talked about often enough, but it happens in WA. Often, conversations centre on victims and perpetrators, warning signs and cycles, breaking points and crises. But what happens next? How do we move toward recovery, reconciliation, and positive change?

We know ferns have existed on Earth for millions of years, but just how closely do ancient ferns resemble modern ones?

By drawing on First Nations knowledge systems, cultural practices, and research methods, this presentation will showcase how climate adaptation and mitigation strategies that respect and integrate Indigenous knowledges and practices can help sustain well being.

Have you ever wondered what it is like working with fossils every day? Helen Ryan from the WA Museum shares her work in discovering, uncovering, preparing and preserving ancient life.

Hear from Dr Amanda Ash from Murdoch University’s School of Medical, Molecular and Forensic Sciences as she delves into the complexity of parasites and their importance.

Join us for a journey into the ancient world with Dr José Galán, a renowned Spanish Egyptologist and director of the Djehuty Project.

Curious about the creators behind our Megalodon head in the Wild Life gallery? Join the makers from CDM: Studio and peek behind the scenes as they share their process of designing, building and delivering museum exhibits.

Discover what we can observe about the Moon, learn about our current knowledge, and understand the importance of returning to its surface!

Discover the elusive Night Parrot at WA Museum Boola Bardip! Join us for an exclusive panel discussion with experts Penny Olsen, Allan Burbidge and Rob Davis.

Join Museum experts Jake Newman-Martin and Linette Umbrello as they take us on a mammalian adventure of the minute kind, from tiny marsupials to giant megafauna.

Discover the remarkable story of Wayne Bergmann, a Nyikina man and Kimberley leader who has dedicated his life to his community, in this moving memoir of living between two cultures.

Celebrate Perth Design Week with a robust panel discussion focusing on design and business.

How much will we look to the language of activism in finding the way towards reconciliation in Australia?

Navigating the delicate balance between the preservation of the Conservation Estate and our cherished and loyal feline companions is both a challenge and a responsibility.