Meet the Museum: The Importance of Parasites

The most common lifestyle on the planet is a parasitic one. Every non-parasitic organism hosts at least one parasite—even parasites have their own parasites!

Despite their reputation, parasites are crucial components of a healthy ecosystem and play a role in maintaining functional immune systems.

Parasitic infections are a significant cause of disease in humans and animals. The patterns of these infections are often complex and difficult to understand. Some parasites are highly specific, infecting only one type of host, while others are more generalist, infecting both animals and humans. These are known as zoonotic parasites.

Hear from Dr Amanda Ash from Murdoch University’s School of Medical, Molecular and Forensic Sciences as she delves into the complexity of parasites and their importance.

Meet the Museum

Are you curious about the fascinating world behind the scenes at the Museum? This monthly program delves into the less visible parts of the Museum's work, as scientists, researchers, historians and curators share their expertise and passions.

-

Episode transcript

[Talks Archive Intro music]

Welcome to the Western Australian Museum Boola Bardip Talks archive. The museum Boola Bardip hosts a series of thought-provoking talks and conversations tackling big issues, questions and ideas, and is delighted to be able to share these with you through the talks archive. The talks archive is recorded on Whadjuk Noongar Boodja. The Western Australian Museum acknowledges and respects the traditional owners of their ancestral lands, waters and skies.

MC: Welcome to Meet the Museum, our monthly talk series. It delves into the less visible parts of the museum's work and also some of our external friends as well, as we have had some talks from external parties recently. Before we begin, I would like to acknowledge that we are meeting on the traditional lands of the Whadjuk Noongar people and pay my respects to elders, past and present. And a little bit of insight if you're not aware, but this area pre-colonization was actually a wetland, and it was an area known to be very important for women's business as well. So personally, I feel very privileged to be here and to be sharing this land. So, I have done our housekeeping duties for this month's Meet the Museum and we are delighted to welcome Doctor Amanda Ash from Murdoch University and Amanda is a senior lecturer in parasitology, had to practice saying that, at Murdoch School of Medical, Molecular and Forensic Sciences. Amanda's research focuses on zoonotic parasites and whilst we as the general public tend to think of parasites as a bad thing, Amanda's here tonight to talk about the complexity of parasites and let us know why they are important components of a healthy ecosystem. So please welcome Doctor Amanda Ash [Audience applause].

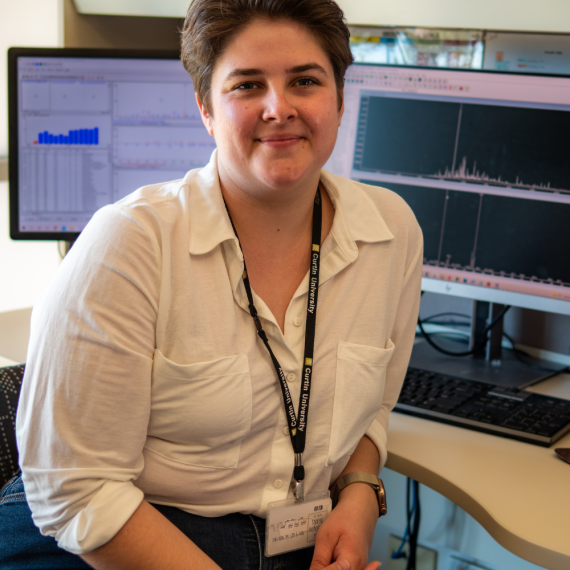

Dr Amanda Ash (AA): Thank you. Cecily, thank you for the lovely invite to come along here and talk to you today about yeah parasites. As Cecily has already told you that I am at Murdoch University. We have a nice, big, beautiful building here called Boola Katijin. I was asked what sort of area I sat in earlier with regards to in the university and I find it quite difficult to, I’m in the sciences, but, I cross a number of different sciences because of the fact that I deal with infectious diseases that cross between humans and animals, and so I therefore teach into our veterinary science course. So, we have 100 or so vets that are going out to treat your animals later. I need to teach them what they need to know about parasites in animals. But I also teach biomedical science, so those that are thinking about areas in the biomedicine areas and needing to know about human parasites. And we also have a laboratory medicine course at Murdoch University and so these students then go out and work in pathology labs. And my part role in that is to try and teach them as much as I can about again parasites, and more about the diagnostic side of things. So, I cross a number of areas in the teaching space, which really kind of reflects my research space. As academics, we spend half our time teaching and the other half of our time doing research. And my research has been about parasitic infections, how to diagnose them, how to treat them, how to control them in a range of different environments. I look at wildlife and I look at what we've termed zoonotic parasites. Those are the ones that naturally transfer between animals and humans, they’re called zoonoses.

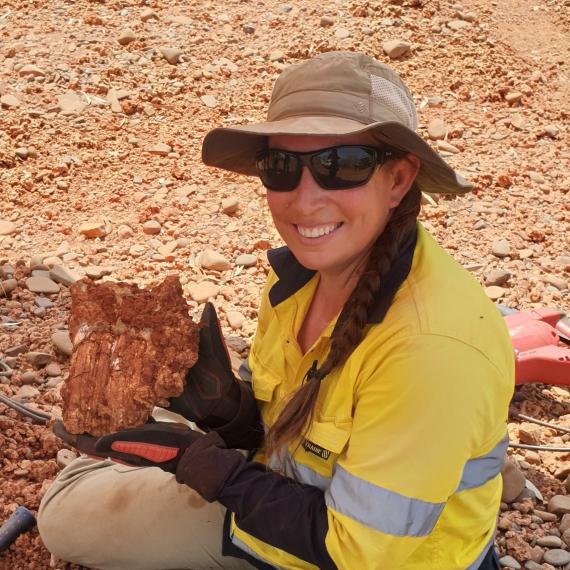

So, a little bit about me. I like doing fieldwork. I sort of started off in my undergrad I did a little bit of parasitology and realized how much fun it was. And so, I ended up doing an Honors program on giraffe. So, I really have started in wildlife really. Giraffe at Singapore Zoo, strangely enough. They were being infected with a particular parasite that they wanted to determine what that was. It's quite an interesting little project, but it made me discover that we didn't really know what wild animals had when it came to parasites and how different were they when where they were to the captive ones. This one actually turned out to be a sheep parasite that the animals were contracting because they were sitting down and grazing because they could in a captive environment, in the wild you will not necessarily see a giraffe sitting down because they get eaten and it’s too hard to get up. And so, yeah it was actually leading to a death of a few animals. And we also discovered that complete drug resistance. So, like in the human world well we know the antimicrobial resistance, in the veterinary world there is a lot of Anthelmintic resistance. So, drugs used to kill worms, a lot of resistance occurring. So, then that led me from there, I went into my PhD, which was chasing African painted dogs around Africa and collecting poo. Because that's a nice, easy way of determining what gastrointestinal parasites that animal had. Anyway from there on, the last ten years or so, I've been working up in northern Laos, chasing a parasite which cycles between pigs and people. This is a zoonotic parasite. It doesn't cause much damage to a pig but in people it can lead to epilepsy by causing cysts in the brain. And so yeah I chased around in the northern parts of there, chasing other pigs or people and navigating bridges. That is supposedly a bridge. But it's I get to meet and experience a lot of fun things. So, I get out and about, and then I get back to the lab and, and do all the laboratory work as well. Although now I've got a PhD students, so they get to do all the laboratory work.

Okay, so let's start with what about the subject parasites. What is parasitism? So, it does actually come from a Greek word which which means one who eats at the table of another, which is literally what we sort of think about parasites. They infect and live off other species known as hosts. So that's the main ‘I'm a host’ if I'm infected with a parasite, benefiting at the expense of their chosen victims. Or in other words, one partner benefits and the other partner does not. Generally, the host which might be me and is harmed and it's usually obligatory for a parasite to have a host. Host doesn't necessarily want to have a parasite. What I want to try and put across to you all, why are parasites important? And I thought of five key things. First one being parasites, are common. Parasites cause disease, which I think you're all probably familiar with that aspect. There's in certain circumstances Australia was a really good example of this, which I'll get to that. Emerging parasitic diseases are occurring, but they're also important parts of ecosystems. And finally, I want to end off with are they actually even good for us? Which I hopefully I will convince you at the end that perhaps they are.

Okay. So yes, parasites are common. I think I heard someone say they're very successful. They are very common. They are the most commonest lifestyle on the planet. Pretty much every nonparasitic species is host to at least one parasite. Probably us in the room are about the only ones on the planet that don't actually have a parasite nowadays because we've pretty much eradicated our parasites here in a developed country, in developing countries not so much. But yes, so I mentioned the Christmas tree is a parasitic plant. So, you can range from parasites in plants all the way through to humans. There's a lot of them.

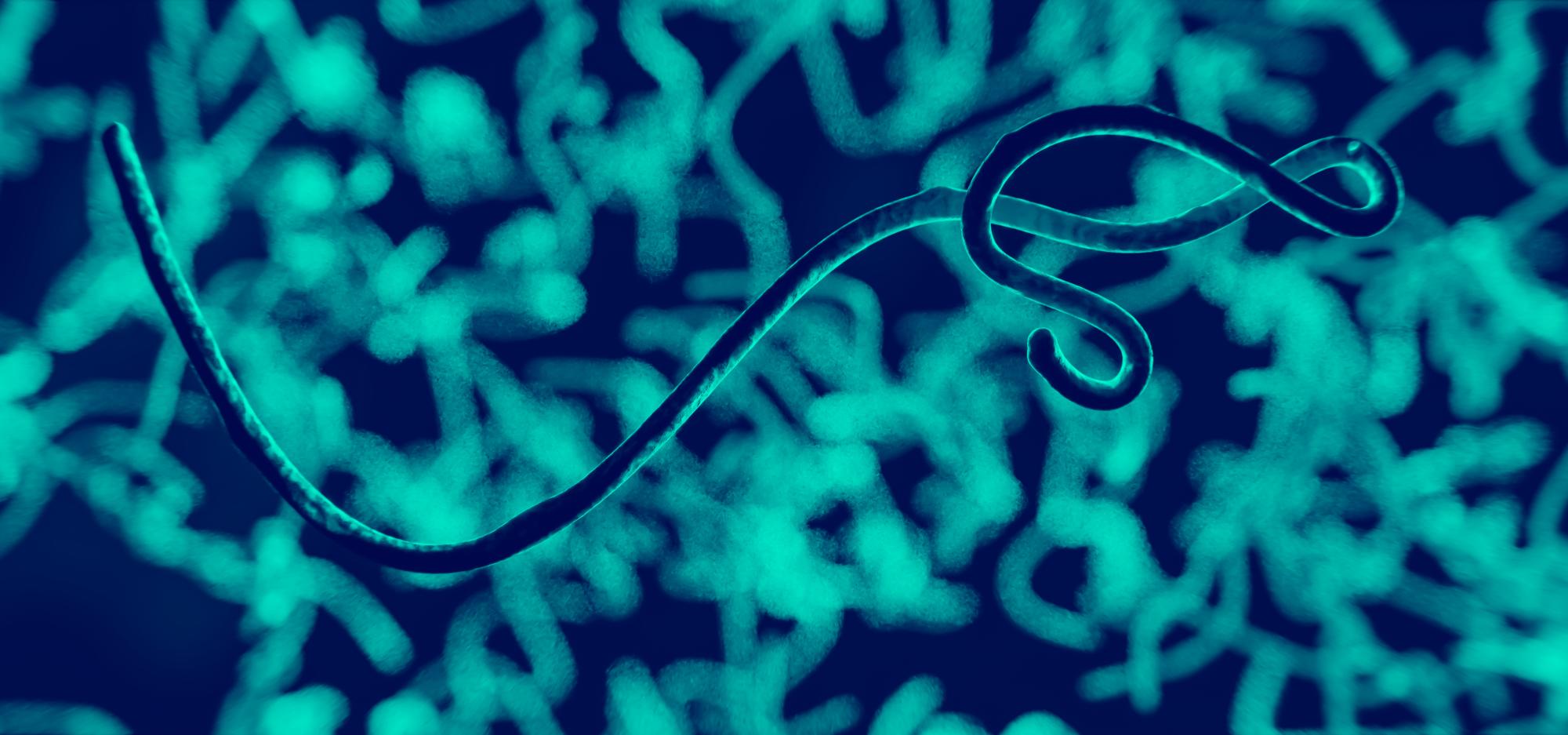

And I brought this [refers to slide]. Even parasites have parasites. So, I was looking down the microscope once, looking at a flea, trying to identify what this flea was, and discovered these little things and if you can see them but they're actually a mite, so even, which is an ectoparasite as well. So even our parasites have parasites. And they've been around for a very, very long time. So pretty much as long as we've had a host, we've had parasites. And this is a nice example of a paper that came out a number of years ago now in science, but they found evidence for the first time, physical evidence of a parasite on a dinosaur feather. So, it was a tick, who's just here [refers to slide]. And it's been blown up here [refers to slide] grasping a dinosaur feather in the up to being essentially 100 million years ago, so there's a lot of them. They've been around for a very long time. And during that time, there has been a lot of coevolution going on. And so we have some really crazy life cycles that occurred. Before I get to that though, just to sort of categorize them a little bit in your head. So I'm not sure looking at parasites, you know, the general term, we kind of think about them in four major groups, or taxa, if you want to be with museum people. We have the small ones, single celled protozoans. We have things we call flat worms, they’re big, flat, they don't have body cavity things. We have round worms. Because they are round, they have body cavities. And then we have, arthropods. So, things that usually attach themselves or bite us. So, the ectoparasites. So that's the four main groups. That I'll show some examples of as we go.

But yes, they all have various life cycles. None of them are all the same. And why they are different is another conversation for another day. But the life cycles are really important to understand if we are going to think about finding them, what are they going to do to the host? Depends on where they might be in the life cycle. So diagnosing, treating and controlling particularly is a big one. How do we stop transmission. If we don't know a lifecycle, then we don't know how to stop transmission. And there's three basic life cycles that exist. I'm using a human host here, but this is this is the same for any any host animals. But so you have direct, that means just goes from the same host to another host. And you have what we call indirect, and this is when another host is involved. So, the parasite has a stage in here, and it has a stage in here and has to get from here to here, which sets up these really crazy life cycles. And this in this case, it's usually someone eating the other.

And then we have, vector-borne parasites. So, they're the ones that are, transmitted through an arthropod, they’re probably the three main transmission pathways. All of our students at Murdoch have to have about six weeks of life cycles. There's a lot of them. So and it's just because it is so important to understand when you're thinking about control, you don't necessarily need to know that. But I just wanted to, introduce you to the basics of parasitology.

So, now that we know life cycles. We can consider now how parasites cause disease. Now, this is what you probably most familiar with that. Yes, they are a cause of disease. Plasmodium, which is the a protozoan, small parasite, blood parasite which causes malaria is probably the most well-known and it's the most pathogenic that we have on the planet. It's endemic in other countries besides Australia. And even up until two years ago, it's still causing, what have I got 241 million cases with over half a million deaths each year.

The other, one that gets touted a lot also is something called soil transmitted helminths. The name really spells exactly what it is. It's a parasite or helminths, nematode that we can contract from contaminated soil, transmitted in the soil. And in countries where this is endemic, it's usually children who are most adversely affected, but currently 1.5 billion people worldwide. Again, the countries here indicating where they exist, it's usually related to a a status of poverty because people don't have, adequate sanitation services, adequate clean water, so you're getting that contaminated environment so you're allowing transmission to occur. I bring that one up, particularly because part of my work, when I was talking about when I work up in northern Laos chasing a parasite that infects pigs and people at the same time while monitoring for parasites, these soil transmitted helminths that people are infected with. And I just wanted to show you some numbers because this is now, as of well earlier in the year we have got some surveys done in the northern parts of Laos.

These are some, some parasite eggs [refers to slide]. That's what I would be seeing. Gastrointestinal worms and we've got prevalence ranging from between 60 and 80 percent within these communities. And when you're looking at I've got some pictures next to show you what communities are looking like, you can see why we have what we have. So, this particular village I've worked in quite a lot and it has one water tap that everybody uses. They don't often have access to that water during the dry season because it's it's reliant on water coming down the mountain. So, it's rainfall related, and they wash themselves, they wash their food and that's pretty much the main use. So, you can say that you're not going to have adequate, clean water.

Toilets, if there are toilets. This is an example of a drop toilet [Refers to slide]. In this particular village when we walked into the village, it had 65 households with about five that actually had toilets. There were some other toilets that had been brought in by some charity organizations but they hadn't considered the fact that water isn't a common access 24/seven throughout the year. So when it was drought they were not using the toilets. And so then they just became not used and got broken. So water was the main thing. And it's you know, kids are usually running around with no shoes and socks. Dogs and animals are very close to the community. So, this is a really common environment where these types of things can occur. So that's why you still have 1.5 billion infections.

We don't have them here in Australia because we've got toilets, and we've got clean water, and we've got drugs. So, all of those things together. So I don't know oh, that's another one [refers to slide]. Yep. All of those things together mean that we've pretty much eradicated any really parasites that we have in the developed world. But yeah, I was bringing the next slide was bringing another one that causes disease. So, whilst we don't have all of those common ones that I just mentioned like Plasmodium, malaria and soul transmitted helminths, we do still have the odd, odd case that comes up. And this is a really nice one that came up just last year, which even I was a little bit grossed about. Sorry, that's the squeaky part.

So yeah. So, a patient in January of 2021, they complained of abdominal pain and diarrhea, followed by constant dry cough and fever. By the following year, that person was suffering from forgetfulness and depression. And when they had an MRI scan, they found this abnormal thing inside her brain. It was successfully removed. And this rather large roundworm was removed from that person's brain [refers to slide]. Now it was identified as this particular name here, Ophidascaris robertsi. Which is actually a roundworm or Ophidascaris from pythons. So knowing what it is now, we now know what the life cycle is. Because we know our life cycles, we can understand how all of this happened. This particular one I know once you ingest the parasitic egg, it does a bit of a wander around the body at the larval stage and it gets usually makes its way to the lungs, and gets coughed up and swallowed. And so this is this abdominal pain, dry cough and fever happening. It's not a natural parasite of a person. So it got lost and just kept wandering and ended up in her brain. I was showing this to some students last year and I had a student say, ‘Poor parasite got lost’, I thought that was a nice way of putting it. Anyway. Yeah. So, this particular person when they looked about the risk factors and how this possibly have occurred, they like to forage for native grasses or native native lettuce, Warrigal Greens for cooking. Not necessarily cooking, I think that was as a salad and in the same area, pythons are found. And so a python has pooped in the area, eggs have got onto that lettuce and she's eaten that lettuce. And that's how it happened. So wrong place, right time for that particular person. So yeah, I mean we have rare occurrences, but, when they do come out, they're, they're a little interesting.

It's also besides the disease aspect and probably this is more important for us in Australia, is the economic burden of parasites. So in people yeah we've eradicated parasites pretty much, in our livestock it's almost impossible to eradicate. And we've got this issue with drug resistance. And so, trying to control parasitic infections in livestock, sheep, cattle, goats, is estimated up to 300 million a year. For us in the pet industry we've got pretty nice, comfy pets nowadays. But fleas are probably the one of the biggest things we still have to worry about. And I don't have a dollar cost there but, it's estimated around $200 a year perhaps on flea treatments. And I think there are about 6 million dogs in Australia. So add that up, you can work out what the annual cost is going to be. So, they are important as a source of disease and economic burden.

Continuing with the disease aspect of it so all those sort of diseases, sort of endemic there, we know that they're there and that's a natural occurrence. But there's also things that are changing our environment, which is allowing for new and emerging parasitic infections, and things that can do that are climate change, changes in land use and the one I'm going to focus on which is the introduction of exotic plants and animals. The climate change, probably one of the ones that they're really worried about at the moment is malaria for instance. It's in particular regions. It's a vector is a mosquito which needs a particular climate. As our climate changes those vectors will move into different areas and you change the geographic distribution of malaria. And so people who have not normally getting infected malaria are going to be getting infected. We don't have malaria in Australia, so I'm not going to worry about that.

But what we do have in Australia is a lot of introduced animals. And introducing these animals has caused a whole plethora of issues for our native animals. So, these are the hosts of successful parasites that have invaded Australia. Starting off with here, we've got the rat, sheep, so the livestock that was brought in with your European farming. We brought in our pets as well. Cats and dogs, and foxes were brought in for hunting I believe. And all of these brought in their parasites, and not always are they going to set up a transmission cycle. It has to have the right hosts. The life cycle needs to be able to be completed depending on what it is. It's not all of them that established, but quite a number of them have, which I want to talk to you about. So, the first one is the cat and the rat and Toxoplasma gondii. Yep. Toxoplasmosis. That's right. Small. It’s one of those protozoans. And the cat is the main host for it. Toxoplasma actually is quite a generalist. It doesn't just infect rats. It infects pretty much every mammal on the planet, including us. But we certainly did not have this in Australia before we brought in cats and rats, because we didn't have cats and rats. And so our wildlife, who thinking of this over an evolutionary time spance is a short period of time that they're actually being exposed to this particular parasite so immune functions haven't been set up and they get hammered quite badly because of this particular parasite. So it's the suspected cause of death and disease of multiple Australian marsupials. All of these, I've got a picture today [refers to slide]. Tassie devil, the quoll, the woylie and kangaroos have all had sort of local outbreaks where toxoplasma has been the blame for their death. And prevalence of around 30 to 40% a commonly reported Toxoplasma can be asymptomatic a lot in most. There's probably half of us in the room are probably infected with Toxoplasma. I would put my hand up that I probably have as well but our immune system usually keeps the infection under control unless for a naive host as well. That's the other issue and these are all naive hosts so they seem to be more adversely affected to Toxoplasma than potentially the rat for instance, is the common intermediate host.

This next one was a really good one. This is the dog and there’s sheep. So we brought in sheep, we brought in dogs. And the dogs brought in a parasite, which we call Echinococcus granulosus, nice big word. It's basically a little tapeworm. Causes disease called Hydatid disease. Here's a lifecycle picture for you [refers to slide]. So this is actually the picture of the worm. I haven't got a scale bar there, but it's basically the size of a grain of rice. It's really small and it only this adult only lives in the dog or canid, kind of can have hundreds of thousands of them in the gastrointestinal system and doesn't really do much. Eggs are excreted in the environment where dog poops and a herbivore who's grazing usually picks up those eggs, and then they get infected with the larval stage. So this is one of those indirect transmission. The larval stage causes these really quite large cysts. I I usually have some quite gross pictures but I thought that I would be really quite nice today, so I've taken all of those out. But this is a radiograph of this large mass here is actually [refers to slide] and this is a Hydatid cyst in the abdomen of a person [Refers to slide]. As I said it's usually sheep and herbivore, a sheep and canids that are on the cycle that humans if they were to ingest those same parasite eggs can end up with the Hydatid cysts in in their organs, and it usually occurs in the liver and or the lungs. You might ask, how would we end up necessarily… not eating dog poo are we? No. But your dog does that. And then you let it do that. So that's one way of that happening. So don't like you don't let your dog lick your face. Although our animals are usually pretty good. Now we brought that in that parasite which cycling between dogs and sheep. Canids and sheep herbivores. And then humans are just one of the accidental hosts. What's happened? There was a huge campaign to get rid of Hydatid disease in Australia. It went on for about 50 years. Which was you had to treat your dogs and you weren't allowed to let your dogs eat animal offal, so so you know self-slaughter on a farm, they might throw the liver and the lungs to the dog to eat for instance. And we were successful to a point. Tasmania is hydatid free. Because you're from Tasmania [refers to audience member]. And New Zealand also had the same issue because I had the exact same problem. And they did a the same program and they're also called claiming themselves to be hydatid free. Mainland Australia will never be Hydatid free because you kind of spill over into the wildlife. And so what we've found now is that kangaroos, our biggest herbivore, are now playing the role of a sheep for instance, and dingoes and foxes are another canid which has successfully picked up the adult parasite. So we will have this life cycle going on mainland Australia forever, because we won't be able to control our dingoes or kangaroos and there's some like poor kangaroos get quite a large, unhappy cysts in their organs.

The other one I want to talk about is pets. Pets and their mites which the mite in particular we'll want to refer to Sarcoptes scabiei. Anyone heard of it? Scabies. Yep. In people it's called scabies. In animals it's called mange. It's still the same genus species. Sarcoptes scabiei, scabies. There is some talk about genetically whether there is some genetic differences between the animal version and the human version, but I would still suspect this is probably a zoonosis that can transmit to people. But it came in probably in several incursions into Australia, but it certainly wasn't here before colonial Europeans. Foxes, dogs, people would have had, has brought in this mite and this mite likes to jump on a number of hosts. But just briefly, why does it cause so much damage? So these are little mites, they invade the hair follicles on your your skin, and they burrow in, make a little nest and then the female lays eggs. Those eggs hatch into little larvae, they move home, jump into another home next door and start destroying that as well. And so that whole lifecycle occurs on the host and can cause quite a lot of damage like this. So yeah, these are a bit ugly images [refers to slide]. But it has spilled over also into our Australian wildlife, and our koalas and wombats particularly seem to be quite adversely affected. Wombats I know have had local extirpation, say local extinctions in areas along the eastern seaboard because of this mite they get so unwell. They don’t feed, can't sleep and so they actually do die. There's been a lot of work on how to go about getting treatment to these animals so, which has been successful.

Closer to home this has come about in the last few years… is our quenda. You'll know our little quenda. So we discovered a local, outbreak on mange. So these are little mites that we saw on the microscope [refers to slide]. This is the damage of quenda. So healthy quenda, unhealthy quenda [refers to slide]. The story of quenda mange was really quite astounding actually because we'd always sort of quite sort of, it's only over the east. You know, the wombats over east have got the problem. And we didn't have mange in our wildlife here. There had been one single case that when we were trawling through the records back in 2007, a Quenda had been reported to have mange. But there was no obvious concern until we had a spike between September 2019 and June 2021 up in the hills near Roleystone, it’s a hotspot if anyone lives there. But yeah, a lot of Quenda were being brought into the rehab centres up there that were looking really, really unwell. And so we had one case in 2007, all of a sudden over this period, we have over 50 animals being brought in. 40% mortality rate, so it really was not being managed well. Diagnosis was confirmed as sarcoptes scabiei and so now we have, we do have sarcoptes scabiei in our wildlife here in Perth. We don't understand why yet or how, probably a spillover from a fox maybe or dogs. It seems to be only in the quenda in the backyard. Now is that because they're coming into backyards because they're unwell and they want an easy feed, or are they coming into backyards and being exposed because of something else that's going on. So that's that's a a question needing to be answered. But our poor old quenda are no longer free of sarcoptes. So that's all the yucky stuff about what parasites do. And I know that's probably what you expected that they are all doing bad things, now and I'm trying to switch channel tunes a bit and sort of show a little bit about the positive aspects of parasites as you go to go there. So the tassie devils no, that's actually a, a cancerous form, a contagious cancer, the tassie devil tumour, facial tumors. Yep. And so it's being transmitted by bites because they like to fight each other tassie devils a lot.

Ecosystem engineers. So, let's have a look at that. Yeah. Sorry I couldn't get this off [Refers to slide]. Parasites can manipulate host affect and that which subsequently affects food webs, mostly on who gets eaten and how parasites can actually manipulate this. They can also affect the outcome of competitive interactions, so who wins or loses? In an infection of view can actually enable coexistence of various species so they're actually sort of really quite good at manipulating or and or driving, a healthy ecosystem. So some examples of manipulating behaviour as to who gets eaten and how. This is a Dicrocoelium [Refers to slide], it’s a fluke, liver fluke of sheep. It has a complicated life cycle, sheep where they have the adult worm, but it goes through snails and ants in different larval stages. This is kind of the case with these flukes. Is sometimes more than you know one, two, three intermediate spots it has to get to, which is when you start thinking about, Why? Just don't. Because they, they just have. It'll come about opportunity and what you know it's, it has nearby that it knows it's going to get from one place to the other, essentially getting back into this animal because that's where it will sexually reproduce and maintain its’ foreverness. But so the larval stage is this go through snails, then go through a lifestyle stage and then go end up in an ant. Now the infected ant, who would normally not be hanging around where it would be eaten, they actually move to the top of the grass and wait there, ‘Hello Sheep! Come and get me’. Which is a complete opposite to what an ant would normally do, particularly during daytime when sheep are grazing. So that's an aspect of a how host behavioural, I mean behavioural manipulation I should say. So behaviour of going to the top of the grass, one that's does both behavioural and physical manipulation is this thing called Leucochloridium. It's a parasite that goes from snails to birds. So snails is the larval stage, needs to be eaten by a bird to get back into the bird, sexually reproduce and continue that way. It's usually the intermediate host which is the worse off because you have to probably be ingested some way. Eaten. So you, you're usually worst off in this whole cycle. And what this one does is, so it's inside the snail, it will move into its’ sort of antennae, well first of all it encourages the snail to go out to the edge of the tree branches, sort of hang out where a bird might see it. Not only does it encourage it to be placed in the wrong spot at the right time, it also then imitates what a caterpillar might look like. And so that therefore attracts a bird to come down and eat this particular snail. Snails not happy, parasite is, Bird probably doesn't really care. And this is, sorry it’s got no pretty pictures, but it was a really nice study that was put out a while ago now, that how predators help infected animals. Preferentially eaten by predators, so again this is how it's sort of manipulating the host, the sorry, the intermediate host to be eaten. So what we have here are three sort of similar kind of small mammals that a hawk will eat, chipmunks, rabbits and squirrels. And what they did was they shot a number of these, not sure how you get the ethics for that now. But they shot a number and they also had a hawk capture the same ones as well. Then they looked at the prevalence of parasites between those that were shot by a gun or captured by a hawk, predated on. Funnily enough the chipmunks and the rabbits, there really wasn't much difference, significant difference, significant difference between, their parasite loads. But there was in the squirrels and the theory that these authors were making was that the squirrels were the hardest ones to catch. Chipmunks and rabbits were not so hard for a hawk, but the squirrels were really hard so the squirrels that were infected with parasites were most likely to be predated on by a hawk than the gun because they were being slowed down, most likely.

And the last one about this sort of ecosystem engineer topic is another [Refers to slide] I did put a picture and big graph, is showing how you could have, how parasites manipulate the coexistence of different hosts that wouldn't ordinarily be able to coexist with each other. And this is just one example, and there are others out there, but I didn't want to go through all those. But this one I thought showed it quite nicely. So it's two fish species, the red one is roach, the yellow one is rudd. The roach is a superior competitor, left on their own rudd would have no hope. Surrealism… I just realised what I just said, I like it… but there's a parasite of roaches which is a tapeworm. This is an example of the tapeworm called Monogenea. Which when the parasite load goes up the population of rudd, roach goes down. So that's the red one. So our green line is the parasite load, red line is roach…can't speak… and rudd is yellow. So when the parasite load gets too high the population of roach decreases which allows the yellow guy to compete because there's not that many red guys around anymore. But as the population of roach disappears, so does the tapeworm. So it starts to increase again and then rudd decreases again, and this will cycle throughout the years. And that's where this particular parasite is actually allowing to fish species to coexist which wouldn't normally be able to do. I thought that was pretty nice.

Right. And the final one, probably the hardest one that I'm going to try and convince you to, but can parasites be actually good for us? I'll start off with a healthy ecosystem. This is a healthy ecosystem. Well, the statement is a healthy ecosystem is one which is rich in parasites. This was a study done, which I couldn't actually find the information on, so apologies. But, they were looking at parasites in a river system on fishes. And what they found was, so if you look along this line here, so river condition score goes up here and this is prevalence of infection. So as prevalence of infection increases, so does the river, so it goes with the river condition. So basically a healthy river condition, healthy river is enabling a lot of parasites, so a lot of infection and also different types of parasites. So this is species richness. So the number of different species within that river system. And again similar thing you've got as species, as river condition goes up, so does species richness. So in this lovely ecosystem here, if it's nice and healthy, it's going to have a nice healthy load of parasitic infections within that environment. When it comes to a host and a parasite, one of the main interactions that occurs is the host and the parasite and the immune system. And that ability of the host outwit the parasite and the parasite to outwit the host has been continuing on and we call it co-adaptation, or an evolutionary arms race, so if you think about it one put one comes in with one, get something bigger and better. I'll get bigger and better, bigger and better bigger and better, and so it goes. And that's really what we sort of determine about this co-adaptation between a host and its parasite, and the and the parasite is really fighting the this sort of thing is our immune system. So it's constantly driving development of our immune system and also genetic diversity of our immune system. Now let me see if I can throw out the evidence. Hygiene hypothesis. Anybody heard of this? Yep, so it's basically saying that we're far too clean for our own good. And particularly at a young age. So at a, at a childhood age, exposure to infections or the lack of exposure to infectious agents, such as gut microorganisms and parasites, increases the susceptibility to a to allergic disease by suppressing the natural development of the immune system. I've actually forgotten what my next slide is. Okay. So what it's basically saying is that, well, we're a good example here in developed countries where, we have managed to eradicate all our parasites, in a relatively short period of time. So here in Australia, probably the last 50, 60 years, have we had good services in to ensure that we don't have our natural like soil transmitted helminths I was talking about, you know the countries that are sitting still at around 60 to 80%. 60 years ago, we probably had not as high, but something. Now, when you think of an evolutionary point of view, that's a really short period of time for an immune system, which was used to fighting these things for 100 million years or however long it's been. So we get rid of those in 50 or 60 years and you've got an immune system going ‘What do I do now? I'm supposed to actually attack this, and I've got nothing to do’ and so this is developed around this hygiene, a policy where to claim we've gotten rid of that pathogen and our immune system has not been trained, particularly at a young at young age to understand what is a pathogen or what is not and so grows up as a really bad adolescent, and starts acting out and going AWOL.And we’re getting all these alert diseases, everything ranging from, I'm going to show the next one, which is Crohn's disease and or ulcerative colitis, has been a good example. Someone asked me, how long have I been looking at, having a parasite passion. Probably around about here is where I sort of went ‘Wow, these guys are really, really crazy’. So, yeah, in 2003, they decided to trial this idea of what would happen if you put a parasite back in to someone who was not well and so they did this with, long term Crohn's sufferers, patients. And they used a pig whip worm. This is my pig [Refers to slide], It's not they weren't giving it to the pig of, just getting a picture of a pig. That's where the parasite hangs out. It's what it looks like. That's the eggs. And the patients were given these eggs, which you couldn't see just in the, in your cordial and whilst, but and it would set up as an adult parasite like that in the gastrointestinal tract. It didn't stay there for a long time because it wasn't a natural parasite of people, it’s very close, pigs and people are quite close. But it wouldn't hang around for too long. What they found was that while patients were infected with this Trichuris or this with worm, they were also symptom free. Which is quite amazing. There were no adverse symptoms, while our infected remission was temporary and repeated doses were needed back in the 2000’s when they trialled this. And they have moved on from a pig whipworm to a hookworm of humans which is called necator americanus. And this is being done by actually by a group, and so the first one was down in the states and this is now being done by a group at JCU in Cairns. And they're continuing on with the work of helminth therapy with and they did this in actually they've done in 2020, actually it’s later than that to treat celiac disease. So, hookworm Is one of those ones where it actually put the larvae in the soil so that the soil transmitted helminths, the larvae in the soil penetrate the skin, and then it will move from, into the circulatory system to the lungs, be coughed up, swallowed, and head back down into the gut where it becomes an adult worm. Quite a crazy little migration. But because of all that interaction with the immune system they are thinking that that is what's actually what the immune system needs is all of that, that interaction. Because other parasites don't necessarily do I, ones that have a really close interaction with the, with the host seem to actually have this ability to mediate an immune function. And so, yeah, so with this hookworm one, they were subjected to gluten challenges and they're finding that patients in this trial, at least they were able to withstand gluten and toxicity levels were greatly reduced. That's still a work in progress.

I was watching one of those crazy shows, Michael Mosley, bless him, had a good one about parasites. And I remember him interviewing a patient or person in a curry house. And it was kind of like, why the curry house? But this person was a Crohn's sufferer, and they were not able to eat anything spicy… Anyone familiar with the disease? But it’s an autoimmune disease. It's, they, immune system actually eat away at the person's intestine, ulcerates it and so you actually sometimes have to have whole pieces of intestine taken out because it's been eaten away by and I... well, immune system, this person was sitting in a curry house having curry because he'd bought of hookworm on the black market somehow, I don't know, I did look it up and apparently you could get some from Central America. You buy a little tube apparently in liquid and you've got these larvae. You put the larvae on it, on his hand like that. And he was a, he had a who claimed infection and he was eating curry. He was happy. This, JCU crowd, I saw them a couple of years ago and, and he had his PhD students around, and a couple of those are ‘You we've got hookworm at the moment!’, because they were in this trial for helping out. I probably if I was to be unlucky enough to actually come down with one of these, I probably would put my hand up for a hookworm. Oh, the ultimate game goal of all of this though, is to try and understand what, what is being promoted or mediated between that host and that immune system to then be able to create a synthetic form of some sort, you know, be able to take a pill with a particular protein in it, which is stimulating the same kind of response that the parasite does. But until this point in time it's, you're going to have to have a parasite instead, so given that they're ecosystem engineers and they're actually probably quite good for us in the end.

They are also one of the mass extinction events happening. So parasites are the sixth mass co-extinction event. As per this person, circa 2000 species of helminth species at risk with Co-extinction. So this is meaning those parasites that are related to their host who is going extinct. So Australia's got the biggest extinction probably record on the planet with our mammals, so all of those mammals that have gone extinct possibly have their own little parasites, and those parasites are gone as well, we never even knew who they were. So, it's really is a risky business being a parasite, especially if you're a host specific parasite. What I mean by that is you don't, you only like one particular host, you don't go jumping on everybody else. You just want one. And there's quite a few of those around, and those are the ones that are at risk with their co-endangered hosts and one close to home which we were involved with the last couple of years and I believe there was a talk about this particular parrot a few months ago which was quite a big session, but the Western Grand parrot. So the Perth Zoo sent us some, some small little lice, they sent them to us and said, ‘Can you tell us what these are?’. The zoo is actually quite good in the fact that they don't they recognize the, the, the goodness of parasites. And unless it causing a problem, then they want to just leave it as is. So we do a lot of monitoring and if things are you know, getting high levels, and they'll think about treatment, but otherwise it's usually just what is it. So their main question here was ‘What is it? Is it host specific to our, to our Western grand parrot, or is it jumped on from another bird or in the same sort of area?’. And because it's birds, only 150 animals left in South West region, so this bird goes extinct, Its parasites do as well. And we have discovered that it is a host specific little louse. It's been named and all, and it's been published. It's got its little name. It took a couple of years to do it though and a taxonomist, and so yes, they won't be treating for ecto-parasites unless there is obvious cause for concern because they want to keep their parasite and their bird together. And another one, also close to home, which evolved out of disease monitoring I guess, the Woylie. So the Woylie. Sorry, critically endangered, only found here. Southwest West Australia and it was going through a population decline.Tthat there's been some really good recovery rate and then they went off in a big decline, and I wanted to know what that was. It wasn't necessarily just predation, it seemed to be maybe it was a disease element to this. And so the poor Woylie has been trapped, and captured and tagged, and bits taken from it and DNA and blood and poo, for a number of years. And, but throughout the looking for disease element, and I think it was still a little bit undecided, but, by doing all of this trapping and investigating, discovered all the ones in yellow to be new parasites that have never been described before, that are most likely host specific to this little guy, the Woylie. So I should the Woylie go, all of these species will also go.

So bringing us back to the end, It's a bit of a careful balance I always think between host and parasite. Yes. They…Oops… Sorry… So on one side they're part of the biodiversity, part of a healthy ecosystem. So the studies tell us they influence ecosystems, the structures of them in a number of ways. I've just given you a few ways. And they're really good by the, apparently of maintaining a healthy immune system because of that arms race has been going on between host and immune system. But then of course on the other side of it, they are the cause of death and disease in people, in our domestic animals and our wildlife. And to sum it all up, I like to call them infectious diseases with personality. Do you agree? Thank you. I've got some references there if you want to do any further reading, but otherwise, thank you for your attention.

[Audience applause]

MC: I think that's a perfect way to sum it up, actually. Yeah. Yeah, definitely. Especially when you get photos like the one of the tapeworm in particular. Other. Yeah. Yeah, it's, yeah it's pretty cool.

AA: This one there. Yeah, yeah, that was on my bedroom floor in a petri dish when I was up in Laos Yeah.

MC: Amazing. Does anyone have any questions for Amanda?

Audience Question 1 (Q1): Weirdly specifically about the quendas? Because I actually have some quendas in my garden with mange at the moment. Is it, do you have a suggestion of what I should do about it?

AA: Are you up in the hills?

Q1: Yes. Darlington specifically.

AA: Okay. Yep, you can contact the rehab centres, okay and let them know they're well aware of, of mange. We used to have an old… well, I should have had it up there... actually there is a, my colleagues at Murdoch have got... I think it's ‘Mange at Murdoch’ with I think it's still, but otherwise, Darling Rangers, they're well aware to look out for it.

Q1: Yeah. Because I noticed a few weeks ago and going ‘Oh, yeah. Okay.’ and that just clicked of what it was.

AA: Yeah. Yep. Yeah. It's mange. They did some trapping sort of in the, to see whether it was spreading out into the sort of the, the non-urban areas close to the peri-urban and they didn't find any evidence on those out in the bush. Yeah, per se, but the ones still being reported seem to be in people's backyards.

Q1: Yeah. Because we have no cats or dogs, but a lot of around the area does, so I thought I’d sort of check. Thank you.

AA: Let Darling Rangers know.

MC: Yeah also potentially Kanyana I would imagine though…

AA: Yep. Yeah, it would be.

MC: Potentially be overrun, anyone else have a question?

Audience Question 2 (Q2): Thank you. What precautions do you take when you're doing your research, and in the field to not get unfriendly parasites?

AA Yeah, usually that's a good question, because by the time I end it with my lectures and students [say] ‘I don't want to travel anywhere, I don't want to eat anything and I just want to stay home.’ I cook, I always make sure my food is cooked, that's one thing, especially when I'm up in the villages and they want to give me stuff okay, so as long as it’s cooked, really well cooked because meat is a good source. But if it's not cooked well, then that's when the parasite can still be alive. If it's cooked, it's going to be dead. And when I am working in those particular areas, being a high-risk area because I'm chasing parasites, then I have on occasion, taken de-wormers when I get home.

Q2: Rabbits introduced into Australia; are they hosts?

AA: Not of any major concern. From these major ones that we're thinking about humans, not that I can think of. They will have their parasites, but none that I'm aware of that are potentially zoonotic.

Q2: And lastly, migratory birds? Is there a problem there?

AA: Potentially migratory birds bring their ectoparasites, so their ticks and their live ticks are a really good reservoir for disease and so yes, from a parasite point of view. Well, we've got someone working on mosquitoes at the moment, and they're finding avian malaria in mosquitoes around Perth, that will be coming from birds. That could then potentially go on to other birds. But certainly, in migratory birds bringing down other diseases I think Japanese encephalitis virus is one of the ones of concern at the moment. It's hit Australia, it's gotten quite down low south, and it will probably be in WA. Well, it is in northern WA, I think already. So migratory birds will bring it down.

MC: Wonderful. And for any other questions for Amanda at all. I’ll come around.

AA: It's happening upstairs.

Audience Question 3 (Q3): Hi. I'm a dog lover. Yes, but I live opposite a sports field and there's a real community of dog walkers. On a typical morning, there could be upwards of 50 dogs circulating the kids sports field. And it's a toilet. I look at it curiously and go ‘I wonder if there's a problem?’. Is there a problem?

AA: Can be. And it has been in the past. There are a number of zoonotic parasites that dogs are host to that will come out and poop. And if we were to talk about that toxicara one a bit like the other, that's the positive one. However, our animals now are really our pampered pooches and most dog owners that I know of routinely worming their dogs so we've pretty much cut transmission. There's still a little bit out there, but there's not a lot now. But it is a reason why we should be picking up dog poo and putting it in the bin. Because you know, it annoys me as well, I see it on especially on sports grounds where I know kids are going to be playing on that sports ground the next day sort of thing, and people letting their dog poo all over the place and not picking it up. So yeah, there is a risk. It's not as bad as what it used to be because we have cut transmission a lot, but there is still risk, yes. I tell people to pick up their poo.

MC Any other questions at all? Oh, sorry. It's good.

Audience Question 4 (Q4): That last thing about the birds that you said, the last disease that you mentioned, I'm sorry I didn't quite catch it, The Japanese one. Yeah. Is that transferable to humans or do we know?

AA: Japanese encephalitis? Yes, that's why it is of concern. It's a virus that has birds and pigs involved. But it can also like with a lot of diseases, that can infect pigs can infect people as well. And it's a mosquito that will transmit it all around those areas. So, your pigs in your birds and your reservoirs, And then that same mosquito bites in bites people. So, they did find a number of human cases over in Victoria, that’s where my family live, because there's a few piggeries up on the north, the Murray River there and that was where it all had occurred. The floods probably that they had a couple of years ago brought down well explosion of mosquitoes, I know at my parents you couldn't walk out the back door without you know mosquitoes coming in from everywhere, so an explosion of mosquitoes. The problem brought down to the north, and then they had things to keep it going. So, yeah, that's how it sets up and that's what yeah, they've got. I think Department of Health here have sentinels out there around the piggeries and so forth, you to check to see whether it if and when it should occur, but you can get a vaccine for it.

Audience Question 5 (Q5): I guess that’s why border force is so tight?

AA: Yes, exactly. Yeah. Sorry. I mean all those invasive ones, there's still others that are parasites that is, that are in our borders but Timor, Papua New Guinea, that will particularly affect our livestock and or our wildlife. And so they do have a lot of security up around the northern, Northern Territory quarantine areas. But the classic one that's come in recently is varroa mite, I don't know if you've heard of that. So that's a mite that infects bees. We didn't have it in Australia. We were spruiking how good we were. We didn't have it, you know the rest of the world had it and beehives are being destroyed all over the place. And then a couple of years ago, it was found in Newcastle and now it's a case of we can't eradicate, we're just going to have to control. So, yeah…

MC: I'm sure if you wouldn't mind, Amanda, if you… I think there might be a couple more questions but we probably have to finish up, if you wouldn't mind hanging around, I'm sure people can I ask you one on one? Thank you so much. So can we please ask you again to thank Doctor Amanda Ash for her fascinating presentation.

[Audience Applause]

Thanks for listening to the talks archive brought to you by the Western Australian Museum Boulevardier. To listen to other episodes, go to visit Dot Museum WA dog after you forward slash episodes. Forward slash conversation where you can hear a range of talks and conversations. The talks archive is recorded on Wadjuk Noongar Boodja. The Western Australian Museum acknowledges and respects the traditional owners of their ancestral lands, waters and skies

More Episodes

Gender-related violence isn’t talked about often enough, but it happens in WA. Often, conversations centre on victims and perpetrators, warning signs and cycles, breaking points and crises. But what happens next? How do we move toward recovery, reconciliation, and positive change?

We know ferns have existed on Earth for millions of years, but just how closely do ancient ferns resemble modern ones?

By drawing on First Nations knowledge systems, cultural practices, and research methods, this presentation will showcase how climate adaptation and mitigation strategies that respect and integrate Indigenous knowledges and practices can help sustain well being.

Have you ever wondered what it is like working with fossils every day? Helen Ryan from the WA Museum shares her work in discovering, uncovering, preparing and preserving ancient life.

Join us for a journey into the ancient world with Dr José Galán, a renowned Spanish Egyptologist and director of the Djehuty Project.

Curious about the creators behind our Megalodon head in the Wild Life gallery? Join the makers from CDM: Studio and peek behind the scenes as they share their process of designing, building and delivering museum exhibits.

Discover what we can observe about the Moon, learn about our current knowledge, and understand the importance of returning to its surface!

Discover the elusive Night Parrot at WA Museum Boola Bardip! Join us for an exclusive panel discussion with experts Penny Olsen, Allan Burbidge and Rob Davis.

Join Museum experts Jake Newman-Martin and Linette Umbrello as they take us on a mammalian adventure of the minute kind, from tiny marsupials to giant megafauna.

Discover the remarkable story of Wayne Bergmann, a Nyikina man and Kimberley leader who has dedicated his life to his community, in this moving memoir of living between two cultures.

Celebrate Perth Design Week with a robust panel discussion focusing on design and business.

Talk series hosted by Geoff Hutchison that explores who our young selves were and what became of them. This week hear from Sabrina Hahn.

Navigating the delicate balance between the preservation of the Conservation Estate and our cherished and loyal feline companions is both a challenge and a responsibility.

How much will we look to the language of activism in finding the way towards reconciliation in Australia?