Meet the Museum: Unlocking Egypt with Dr Galan

Join us for a journey into the ancient world with Dr José Galán, a renowned Spanish Egyptologist and director of the Djehuty Project.

Dr Galán visits Boola Bardip on his Australian tour, bringing his renowned expertise in Egyptology. Since 2002, he has led the Spanish mission excavating Dra Abu el-Naga, a burial site for the Theban Royal family and elite of the 17th and early 18th Dynasty. The Djehuty Project focuses on the tombs of Hery, who managed granaries for Ahhotep, and Djehuty, who served Pharaoh Hatshepsut as a treasury official.

Discover insights into the unusual discovery of a 4,000-year-old funerary garden and its links to Egyptian iconography.

About Dr José Galán

Dr. José Galán is an eminent Spanish Egyptologist and a Research Professor at the Spanish National Research Council in the Institute of Mediterranean and Near Eastern Languages and Cultures. He has lectured at universities in Spain, the USA, South America, and Australia, and has authored numerous academic publications.

Meet the Museum

Are you curious about the fascinating world behind the scenes at the Museum? This monthly program delves into the less visible parts of the Museum’s work, as scientists, researchers, historians and curators share their expertise and passions.

-

Episode transcript

[Recording] You're listening to the Western Australian Museum Boola Bardip talks archive. The WA Museum Boola Bardip hosts a series of thought-provoking talks and conversations tackling big issues, questions and ideas, and is delighted to be able to share these with you through the talks archive. The talks archive is recorded on Whadjuk Nyoongar Boodjar. The Western Australian Museum acknowledges and respects the traditional owners of their ancestral lands, waters and skies.

MC: Hello and good evening. It's lovely to see such a big crowd tonight. So welcome to Meet the Museum, our monthly talk series that delves into the less visible parts of the museum's work as our scientists, researchers, historians, curators, and visiting guests share their expertise and passions. So before we begin, I would just like to acknowledge that we are meeting tonight on the traditional lands of the Whadjuk Nyoongar people and pay my respects to elders, past and present, and extend a welcome to any First Nations people with us here tonight.

Now for tonight's Meet the Museum we are absolutely delighted to welcome a very special guest all the way from Spain via Egypt or Egypt via Spain, Doctor Jose Galan who is currently visiting Australia. We would like to sincerely thank Heather Tunmore, an honorary associate of the Museum, for organizing Doctor Galan to visit here this evening. And I'm sure, Moya, you've had something to do with it also.

Moya: Yes.

MC: Wonderful, thank you. So, Doctor Jose Galan is an eminent Egyptologist who was a research professor with the Spanish National Research Council in the Institute of Mediterranean and Near Eastern Languages and Cultures. That's quite a long title. He has lectured in many countries around the world and is a recipient of the Gale Visiting Scholarship, sorry fellowship of Macquarie University, which is bringing him to Sydney, Melbourne and Perth to give lectures and also talk with lucky school students. So this evening Dr Galan will be speaking about a Garden for Eternity discovered in ancient Thebes. And I will leave it to Doctor Galen to expand on this. And it's an absolute delight to have Dr Galan here to present this evening. Please welcome him.

Dr Jose Galan: Hello. Good afternoon. Thank you for coming tonight. Today? This evening. I have to thank the museum for organizing this talk. And to Heather, who was the interim mediator between the museum and myself. Since I was a kid, for me, it was a dream to come to Australia. I always loved nature and wild animals and nice people. So it was a great opportunity when I was asked to come to Sydney and to Perth to give talks, and my expectations have been actually much surpassed. I have had a great time in the East Coast, but in the West Coast also, I have had the chance with Heather's husband to go to see whales, which has been a dream accomplished. And, well, I'm here today to speak about my life, which is this project in ancient Egypt. I hope you will have a good time and at the same time, learn a little bit about this ancient culture, which, despite the time difference and the spatial difference that is between us, there are many, many features in common between this ancient civilization and ours nowadays. Today I will focus on a very specific discovery that we made in 2007 and that we are still researching, which I think is quite remarkable. And I wanted to share it with you in a more depth, in more depth than showing other things. Well, we have been now working in Luxor for 23 years. Luxor is the southern capital of ancient Egypt and also of modern Egypt. It's 600km south of Cairo, and it's where the famous Valley of the Kings is located, where the tombs of the Pharaohs were built, many, many years ago. The modern city of Luxor, as you see in the screen, it's located on the East Bank and it actually was developed on top of the ancient city. The ancient city actually grew or developed around two temples, the Temple of Karnak in the north and the Temple of Luxor in the south. Separated by almost four kilometers, three and a half. And actually, the city developed around these two temples because as in medieval cathedral in Europe, the churches and the temples were not only religious places but also economic places. So that's why the cities tended to develop around these temples in Egypt and in Europe too. So we do not know much about the settlement, the ancient settlement of ancient Thebes. Luckily, the people that were living in the Eastern Bank were buried in the Western Bank and in the Western Bank, as you can see, doesn't have so much, so many houses. And the ancient Egyptians chose to be buried in this other side of the river because it’s where the sun was setting. The ancient Egyptian belief is that they would be able to live forever if they managed to jump on top of the shoulder back at the sunset and then during the night go underground with the sun and be reborn again the morning after, in the other side. So they thought that the sun in a way, of course they were not stupid, but this, they were very symbolic oriented. They thought that the sun sort of died and, and live again daily. They knew they were going to die. They knew they were not going to live eternally physically. But their aspirations were to be reborn later on as the sun was. So they, they were buried. They choose to locate their tombs in this side so that they will have a better chance to jump on the solar barrack when the sun touched that, this horizon. So let's go, move a little bit further, yeah. This is the area where we are working on. We are working on the northern end of the Theban Necropolis. The Theban Necropolis as the settlement is about three, 3.5km long from south to north. We are in the very north of the Theban Necropolis. Actually, if you have been in Egypt it’s where you make a turn left to go to the Valley of the King. So we are very close to where the Pharaohs were buried. We are very close to the house that was used by Howard Carter when he was working in, in the tomb of Tutankhamun. And we are right across from the Temple of Karnak. So we are in the middle of the hurricane. Actually, the Kings of Egypt, before being buried in the Valley of the Kings, they were buried in the hills of Dra Abu El-Naga. So actually, it was a woman who inaugurated the Valley of the Kings. It was a queen called Hatshepsut, the first one who was buried in the Valley of the Kings. Before Hatshepsut the seven kings were buried in our little hill. So, this is a picture taken from a balloon in 2004. So this was our second season of excavations. So as you can see here, our site was located very close to the modern village. It was right after the modern village. And we started 24 years ago, focusing on two rock-cut tombs of two high officials that lived, one under Hatshepsut himself, he was the overseer of the treasure called Djehuty, and his neighbor was called Hery. He also lived under a prominent woman called Ahhotep, she was the king's mother and royal wife, and he worked as overseer of the granaries of Ahhotep. So it's funny that our main, two main characters actually served under two prominent women, Hatshepsut and, and under Queen Ahhotep. But today we will not talk about them. They have beautiful tombs that are now open to the public. We have restored them and they are wonderful and they are worth visiting if you go back to Egypt.

I'm going to talk today about what we found under the modern houses. So this is a picture taken in 2004. You see the proximity with the houses. This other picture anticipates what I will talk about. The modern village of Dra Abu El-Naga was demolished in 2006. The Governor of Luxor, together with the Ministry of Antiquities, decided to demolish the town because the houses didn't have modern facilities. They didn't have modern water, electricity they did have, but they were on archeological ground, sort of illegal and with no facilities. So the Governor of Luxor built for them new houses with modern facilities nearby, and they were moved there. And then the houses were demolished. But they never thought that when you demolish a house, you have to clean what you have demolished. So we were quick enough to offer ourselves to clean a little part of that rubbish in exchange of getting an extension of our site.

So for the first seasons we were concentrating in the tombs of Djehuty and Hery, but after 2006 we cleaned this area marked in green and we started excavating underneath the houses. So this is the extension that we will eventually get. I only did like 80m south, but very, as you will see, very, very dense. So these are the houses. They are actually our workmen. Some of them are workmen live here. This is the house of the family of the kid who was serving us tea every morning, the family Bulbul. This is Mohammad, who was a big guy, the man in charge of providing us with water with his donkey and this, this thing, this device. So this were part of our friends and workmen. The houses, as I said, were demolished in the winter of 2006- 2007. We applied for the extension in 2008. We got it and we spent three years cleaning the debris. So after we clean the debris, we call it sector ten, and we started working underneath the houses. What no one expected, including us, is that underneath the houses we will find the burials of the royal family and courtiers of the 17th dynasty. Which is this dynasty before Hatshepsut, before moving to the Valley of the Kings. So this, in this picture, you see the modern houses overlapped, but with what we were about to find under them. The rectangles are shafts or pits, were used as tombs. And you also see mud brick chapels where the offerings were made. And these rectangular, rectangle divided into a grid is the garden that, that we'll talk about. So all this was under the houses.

In archaeology, it’s something that is kind of weird and we learn with time, is that it tends to happen the opposite that what you expect. So if you see the houses, you would say, well everything would be destroyed. But actually it's the other way around. The houses protected the burials. They didn't know about them and protected their burials.

So I will start with this tomb that was under the houses, a big rock-cut tomb, of 2000 BC, which means 4000 years ago. Actually this tomb was robbed in antiquity and also in modern times. And as you see here this is the entrance to the rock-cut tomb and the robbers have made this semicircle so that they could go inside without the need of going all the way down. This was actually one of the few tombs where the inhabitants of the houses knew about it. They made a hole in the sitting room, and they were accessing this tomb through a hole instead of watching TV, which might have been much better. They were going down the tomb. However, despite that they were accessing this tomb, we found quite a number of interesting objects. This is Kamal, one of our workmen inside the tomb, and the light that is coming down is coming from a hole that connected with the house when it was standing up. But actually they were coming down and they were moving around, but of course they didn't have the means to move huge amounts of, of sand, of Earth. So even though we found inside papers dating to 2004, actually, as you will see we found quite a number of things. So this is the house and this is the hole. So we know perfectly well, who was getting inside this tomb. We will not say names. So this is how the tombs look like. It's, so this is a 4000 year old tomb. It's not decorated in this time period, very few tombs got decorated, and it's full of debris, full of sand. As we started excavating one remarkable thing that we found was a huge amount of linen cloth, of textiles. When I say a huge amount, I say tons. We didn't know what to do with so many, so many clothes. And they were amazingly preserved. Some of them are preserved in such a way that they look as if they have done yesterday, but they are 3000 years old. This is their clothes date to year 900 BC, so almost 3000 years old. And you can see the fringes and the color, the blue color. We didn't do anything to this cloth. It was found like this. Some of the cloths I have, for us, lucky, because we want to retrieve as much information as possible. One of the clothes, cloths even had the name of the owner written in hieroglyphs with red ink. In this part, like this one. Actually, we did find clothes with one name and clay figurines with the same name. In this case, this guy was called Amenhotep and he was a priest, probably in Karnak. And we have the year date of the production of the cloth. This is the way the Egyptians wrote the name, this is Amenhotep. This is the title, high priest of Amun. Then this is the year date, this is the word for year, rnpt. This is the sign for ten, then you have six strokes to make16. And through this clay figurine and other evidence that actually comes, I think right after, we know that this guy lived under King Osorkon I. So, we know that this cloth was produced in year 16 of King Osorkon I, around 900 BC. It's really a miracle that we can know the tiny details of this.

The, the modern robbers, well, the robbers in general look for things that they can sell. Modern robbers will take away everything because tourists will buy anything. Ancient robbers were looking for metals and precious stones, and, but they were always working with little light and in haste. They didn't want to be caught. So sometimes they left behind actually what they were looking for because they didn't, they didn't see it in the dark. So actually they were looking for gold and precious stones that were part of the funerary equipment, but they knew also that sometimes the mummies, the mummified individuals had amulets with them made of gold or precious stones, so they rip apart the human mummies looking for gold. So when we work here we found human bodies completely broken into pieces. But still, like this is a torso of a mummy still with a lot of information. This is the torso of a mummy, and the mummies, in order to be to preserve the body, what the embalmers did was to make a cut in one side and remove the viscera. They remove the stomach, the intestines, everything and they will fill again the body with linen, salt and sand. The idea was to dry the body because humidity is what deteriorates all the organic material. So they, they wanted to desiccate the body, and then they will treat it with resins and then wrap it in, in linen. So, in order to get the best throughout the embalmers will make a cut and do all what I have said, and then they will close the cut and they will put a little amulet, like a charm, to avoid like the bad spirits to go inside the body, or the, or bacteria that will deteriorate the body. So, here we have the torso of a mummy that has been has been very badly treated. This is the the, inguinal incision through which the viscera went out. And there, with our physical anthropologist, we found one of these plaques that was closing the cut. This is a, these plaques are not so numerous, not so well-known. About 20 or 30 of them are spread in different museums, but very, very few have been found in situ. This is a wonderful location to see exactly how this plaque was set in their cut. And this is Jesus trying to remove the plaque because the plaque was attached to the body with resins. And as you see it was used an amulet because the metal was engraved with the Eye of Horos. The Eye of Horus is a mythological sign or symbol that for the ancient Egyptians was, had, it was the main protection amulet that you can have. The Eye of Horus was very common to be used as amulet, and in this case it was engraved in this plaque. This plaque is also very interesting because it looks as if it was made of silver, but it was made of tin, and tin in ancient times was a very precious metal, very rare. Actually, in this time tin was produced in the UK and in Spain. So we have to imagine this thing coming from UK or Spain going all the way to the other side of the Mediterranean to be used in this tiny break in this mummy. We are talking about 900 BC, 2900 years ago.

Another mummy that we found broken into pieces, the head has been taken apart and taken away. There is one arm left and of course the legs. This mummy also had a peculiar surprise in the embalming process. The ancient embalmers will remove all the viscera except the heart. The heart will usually will be left inside because it was the organ that would be judged in the final judgment. The idea of the final judgment in order to achieve eternal life comes from ancient Egypt. And the ancient Egyptians have the idea that in the final judgment not only your actions will be judged but also your intentions, because you can sin with your intentions. Like you can kill someone, but you can ask someone to kill another guy. You don't do it but you are the, the, the promoter, let's say. So it's your intentions that have to be judged, not only your actions. And that is why in the final judgment, in the scale, you have the heart against the light feather that they call maat, which was truth or justice. And your heart should be not heavier than justice, and then you will succeed and achieve eternal life. In this case, the heart has been removed. It's an exception. And instead of the heart, for whatever reason we don't know, maybe when the embalmers removed the viscera they made a mistake and they remove the heart also. So they put some ochre, sand with ochre, in the place of the heart and this tiny little black things. And this tiny little black things that you can see here that we removed carefully with the help of the restorers, we clean them to find that they were golden amulets that someone would have used as a necklace. And you see again here the Eye of Horus, the heart, the goddess Mut, the djed pillar, the knot of ISIS, ...[spelling of last item unknown]. So they, male or female, would have wore this, this, necklace as an amulet. No, of course, after placing this necklace on the, on the, where the heart was supposed to be, they pour resins and the resins turned black the necklace, and that is why it was not spotted by the thieves.

So if we move inside the tomb, we reached like the original burial chambers, and this shaft here. The ancient thieves rob this tomb and they threw out what they didn't, what they thought was not of any value like pottery vessels. So here we have Ibrahim and Hassan with one of our archeologists, Carlos, taking notes of the excavation of this dumping area of the ancient robbers. This is Ibrahim who has been working with me now for 23 years. We are good friends. He is an excellent excavator. And whenever we find something delicate it's him or Jamal, the ones who are responsible for excavating. Actually, the physical action of excavating is being done by the Egyptians, by the locals, who are much better excavators than us. They have been doing that since they were six. They know how to do it so well. And whenever they find something weird, something uncommon, they will call you. And we are there as technicians, taking notes, documenting everything but the actual excavation and so half of the merit of our success is theirs, at least half. So this is one pot, and this pot is actually much more ancient than one that I have just shown you. I have shown you mummies torn apart of year 900, but actually the tomb was much older. It was reused then. The tomb actually dates to year 2000 BC. So at that time it was abandoned. And the people in the year 900 used this empty tomb to bury their relatives. But the tomb through the pottery and other and material culture elements it can be dated much, much older to the year 2000 BC. Like this little pot here. We also found these big jars in good shape because there wasn't, the robbers had no value for them. And we found these little wooden objects that are, I should have brought you like a model, but these actually are little dolls. Little dolls that had curly hair on top. This would be like the head. This is the dress, like Nubian style dress with a giraffe painted in here. And these were dolls. And it's interesting because in the Egyptian tombs, very often we found, we find toys. We find, we find toys because they thought that sometimes you can get reborn as a child. So, not only you need food and sandals as we would see, or clothes, but also you don't want to get bored in an eternal life. So you have plenty of time supposedly. So it was very common to have musical instruments or to have toys with you. And this is what we call a paddle doll. Very common of this time period, 2000 BC. We also, I found clay, clay trays to make libations, to make offerings. Also very typical of this date, 2000 BC. There's another team member [unclear name], who is now working for the Macquarie University in Sydney together at the same time as she does for us. She has also a part time contract with Macquarie University precisely to study these kind of objects that she wrote her dissertation about them.

Now, finally going out of the tomb, we go out of the tomb, let's see what we found. When we started excavating outside the tomb you always have like, a wish or a hypothesis. We don't have decoration inside, we don't know the name of the first owner of the tomb. Maybe if we excavate outside we will find the door, the door jambs and the lintel with the name of the owner. So we will know more about him. So I was hoping to find some inscription that will tell us the name of the owner. In archeology, as in life, if you look for something you will not find it, but you will find something else. It's serendipity. No, serendipitous.

So we started excavating outside and the first thing we found is again, this vase, also dating to year 2000. Wonderful. It's white because it's made not with mud as the daily pottery, but it was used, they used the sand of the desert, and it's called marl clay. And they are first quality. And when we start descending the first thing that came to light was a piece of wood standing up vertically, very strange. We did not know what it was. And as we continued we realized that it’s the trunk of a tree still standing up with the root going towards a more humid area. This is David, another of our archeologist of our team. And you have to realize that archeology works in a reverse way, like the more modern things are up, the older things are down. So as we go down it’s as we go back in time. But then to understand things, you have to do them back and start from the more ancient to the more modern. So here when we started going down we did not know what it was. And as we go down, we go back in time. And this would be the time period of when the tree grew, which is as the pottery telling us 2000 B.C. so 4000 years old. This is the tree as it was standing. It's really a miracle. We, thanks to the, that we can see the section of the trunk. We know that it's a tamarisk, and we know from the rings that it lived at least 30 years. Not much. So it would be, it would have been like a bush. Tamarisk are common today in Egypt. This is the hotel where we have been staying for 23 years. Not any longer. And in front of it, you have these huge tamarisk trees. Ours would have been much smaller. But this gives you an idea of how our tamarisks look like. This is again Ibrahim, dealing with a delicate situation with the root of the tree. And as we continued we realized that the tree was connected with a mud and mud brick structure and that the root actually was going towards the middle of this structure. At the very beginning we didn't know what it was, but then we realized that it was actually a little garden divided into square plots. It's what we call a great garden. But in modern times they are better known as waffle gardens or square food gardens. But, so the idea is that each square will hold a plant, a different plant, and when you pour water because it's..., the mud is done in such a way that the water will, will be preserved or kept longer than, as if it was a pot.

So, another interesting thing is when we, actually we have our very good website, and we do have our digging diaries since the very beginning, in the year 2002, we keep a digging diary. And, I am the one who writes it and chooses some photos. And the day before I put some photos of this structure without knowing yet what was it. And suddenly a colleague from Germany, from Heidelberg wrote me an email saying, have you realized you have a garden? And it was very nice to realize that the digging diary is meant for Spanish speakers and therefore by a general public. I never thought that a colleague in Heidelberg will be following us, you know, through the digging diary, which is kind of nice.

Well, so this is John Mulligan excavating this very fragile structure made of mud and mud brick. And you see the root of the tree going towards the middle. And the, and you see the structure coming up. The garden is actually quite small, is three meters by two meters and a half, divided into squares. And, at the beginning, I thought it was a model garden because it's too small. But actually, for a household or for an individual, you don't need more. And actually gardens, not only in ancient times and in modern times, gardens associated with the house do not need to be much larger. So it's actually a garden that the owner of the tomb wanted to have near, so that he will have the source of supplies for his offering table as close as possible. So this is the relationship between the garden and the tomb. And actually, what is something in Egypt, everything is like a miracle. It's, it's overwhelming. We have the floor that connects the garden with the tomb. No, this vase is in situ. It's on top of the floor, and around this spot we have the footsteps of the people that walk around in 2000 BC, as you see here, which is really remarkable. And you say, okay, so footsteps, what's the point? But the thing is that it's a, it's, I think fascinating to realize that, I mean, they were like humans, like us. And of course, they left footprints, but it's a way to remind us that, it's, there is a continuum between their culture and their way of life and ours. And these little details, that can be at first glance taken as insignificant, actually they are all the way around. They bring to life the people that moved around.

So. Oh, another detail, maybe I will go now into a tour Egyptological talk, but well, I think you will be able to follow me. And it's part of our job, you understand what goes inside our minds. When we excavated the, outside the tomb, we realized that the garden was not touching the bedrock but was on top of a half a meter debris. And that was telling us that the garden actually was not built for the first owner of the tomb. It was built later on when the courtyard was filled with debris. What happens is that in Egypt, because of the wind and the water, the things can, like half a meter of debris can, can be like only ten, ten years. So the first owner, through the pottery, can be dated to the 11th dynasty, 2000 BC. And the one who built this garden went later, but maybe only ten years later. But is not the first one. And actually, if we go inside the tomb, this is this is the ceiling of the entrance to the tomb. And it doesn't go all the way down, but it's on top of half a meter of the brick. So the first owner built the tomb and put himself, no he didn't put himself, but the relatives put him inside. Ten years later the tomb was partially covered with half a meter of debris. Also the courtyard. I'm not going to bother, I flatten, did not care to clean the area. They said no, I'm not going to bother, I flattened the debris this hand and I go from there. So the, the ceiling doesn't go until the very, very, until down to the bedrock and outside either. But again, this can be taken as individuals of the same time period.

So this is the garden. This is how we studied it. It's interesting because the garden is very well thought. The squares are made 30 by 30cm because that's the water that we need from the vessels they were using. As time went on, I will show you later, the vessels changed and became bigger, and so the squares became bigger. So the size of the square is directly related with the size of the pots that the water carriers were using. And of course, they were pouring water in each of the square. Or like one pot here, one pot here, one pot here. So eventually became a very humid area. But if it's too humid it will crumble. So what they did is to do like a little channel to separate the humid area from the surrounding wall and the surrounding wall in order to make it more strong, they cover it with more white mortar, white lime mortar. So this was supposed to be dry while this was supposed to be humid. This is the detail of the, of the of the squares. This is how it was built. In the center we have two squares that are bigger and we don't know what was planted because we didn't find any botanical remains inside. But it's interesting that they are different from the rest. They were raised up and in the center they have this slightly darker soil that we thought maybe it's for a tree or the remains of a tree or a bush, but we didn't find anything. So there are these two squares that we don't know exactly for what where they used.

Now. Oh, once you discover this, you have the idea an archeological dig is not to discover things, but to understand the culture, the daily life, the religion, etc.. So, there is actually little merit in finding the garden, but now the merit comes to understand it and publish it correctly. So now comes the, after digging, to look for, if this kind of gardens were common in Egypt or not.

So the first attestation that we have of a great garden comes from, actually from a temple, the temple, the scholar temple of King Nyuserre. And it's about 2380 B.C., so three hundreds older than our garden. And in this depiction, we see a guy pulling some plant, and behind them, behind him, another type of plant. And now, from looking for parallels, we can say that this is a type of lettuce. It's called spiky tall leaf lettuce. And this is probably flax, to make linen. And this can only be deduced by looking for more parallels. In this other tomb of the same time period, under King Nyuserre, we have the guys who were in charge of the manicure of the king. Very peculiar. They have this big tableau showing different activities that take place in the fields. Near the marshes, again we have the same or similar scene of a guy pulling out the same plant, a lettuce. And here again, pulling out another lettuce with the same tall plant that we have seen before. What is interesting in thess scenes is that they for many years, the Egyptologists, have known this is scene as daily life scenes, but actually they are not so. Because the inscription that will, that was written on top of it will say, this is the funerary state for the benefit of the owner of the tomb. So actually, it's true that these actions were, were carried out in a in a daily life, but this in particular was a meant, these actions and all these products were meant for the funerary cult of the owner. So these lettuces will not go to a house, but will go to a tomb. So for us it's interesting to stress this specific detail. In this other tomb that is open to the public, and everyone who goes to Saqqara will visit the Tomb of Mereruka. In the Tomb of the Master of Mereruka, in Saqqara, includes for the first time, like a very, very big square grid garden again in a marshland environment. And as you see again, the workmen that are working in the garden are pulling out lettuces and behind the lettuces is the same tall plant, probably flax. And here you see the pots that the water carriers are carrying are quite small, are globular jars that will add water one by one, the squares of the garden.

If we move down time this is at the end of the dynasty six, and we have a similar scene. This is a block from a mastaba that was very much robbed. And the blocks are spread all over different museums. And this block comes from Berlin. And you see again, this guy pulling out onions. What this funny is that, sorry lettuces, what is funny is that the inscription here says doing the onions, but these are not onions. And it is funny, it's also interesting in ancient Egyptian art, usually image and text, they go together and they match together nicely. But sometimes, either by accident or intentionally, they do not match because the people that were writing were different than the people that were doing the figurative decorations. So the scribe wrote doing onions, but the artist represented lettuces and probably flax again.

These tombs are very badly preserved, but are important for us because are contemporary to our garden. These tombs date to the year 2000 BC, are located in Beni Hassan, in Middle Egypt. And they are interesting because, particularly this one, because it associates a square grid garden here with the production of linen. And this is a circumstantial argument to argue that the plant that goes with the lettuces is linen. And people that know about linen, more than me which is easy, they say no, linen will not be cultivated in a square grid garden, they need a bigger thing. And it's true that probably they were cultivated right outside. But there is a clear association between lettuce of the garden and flax and linen. And there is something in botany that is called a beneficiary association of plants. And it seems that flax and lettuce were much together and they were planted, nearby. Not exactly one in the squares, the lettuces yes were planted in the squares, but the flax was planted nearby. And here in this composition you have the lettuce, and what is between the man and the lettuce could be flax that is then taken to the linen weavers. So, this is how the tomb is preserved. This tomb also is interesting for us because it shows that in one side of the garden there was a staircase used by the water carriers to reach the central squares. And in our little garden, we do have a staircase one side that was used by the water carriers. So our version of a square grid garden matches exactly the iconographical representation of it. In a nearby tomb also in Beni Hassan we have more or less the same scene with the square grid garden and the guys watering the squares. It unfortunately is very badly preserved. A French guy passed by in 1831, made a drawing, then through his drawing we can see that the artist represented plants in each square. And here, apparently, we have onions, finally. And another plant that is not onions, but could be a flax.

And to finish this repertoire, this is a privilege for you to see and for me to show you. This is a tomb that has very recently been found by an Egyptian team working next to us in Dra Abu El-Naga. And they have found a wonderful tomb of the time of Thutmose III. So time of Thutmose III is right after Hatshepsut, so the time of Djehuty. And in this depiction, it’s wonderful, there are amazing things. It is the first time that a guy is represented fishing with a rod. He’s fishing with a rod and catching two fishes at the same time. This became, not a common scene, but it was represented years later. So we know about ten, or yeah, about ten other examples but this is the earliest one. And in the upper register we have a very interesting representation of a great garden being watered by a water carrier next to a house. Not a tomb, not a temple, but a house. This house is very interesting by itself because it's a two floor house, two story house that has two windows through which there are two women going out and catching grapes from a palm tree. What is interesting is that they actually, the designers of the scene first depicted the scene here, and you can see it in red with the women coming out of the window. But then they thought they wanted to include something more. So they did the same scene in a smaller scale next to it, so that they will have room for the garden and the fishing. So you can see here how the artist changed their first designs. And this is again very interesting, the Association of the Great Garden with a house. And finally I forgot about this tomb. This is a fantastic tomb, not open to the public. Of the gardener of Thutmose III, of [name unclear] III. He was in charge of bringing floral bouquets to Amun. His tomb is a wonderful tomb, unfortunately very much damage, with grapes represented on the ceiling. A big, big banquet scene and a garden in the lower bottom of the wall. Unfortunately very bad damaged. This is an interesting association, because the garden is represented under the banquet because the garden was the source of the vegetables that will be consumed in the banquet. So this is the idea. This is a drawing, made from what was left on the wall of the scene, and you can see here a lot of large square grid gardens near the marshes, etc. being supervised by the overseer of the floral bouquets for Amun.

And finally, this is like the Egyptians had a great sense of humor like today also. So, in a little town called De la Medina, where the artist live, we found a number of what we call Ostraca limestone chips that were used to make sketches before the decoration of the tomb or for different reasons. And here is, like, a humorous vignette depicting monkeys watering the garden. And it's true that for the ancient Egyptians to be a gardener it was not a very, a very interesting job. It was very hard and very tiring. There is actually a composition saying how difficult was the job of being gardener and that goes very well with this humorous scene.

Now, we have been, I have been showing you representations of gardens in tombs. What about temples? Actually, in contemporary to our garden in the Little Shrine of Jesus, there is the first in [unclear name], the first in Karnak, we have a representation of the God Amun with big, big lettuces coming out of a square grid garden. In the red Chapel of Hatshepsut, also we have the Bach Shrine of Amun on top of an altar. And below the altar we have a representation of a Great garden with lettuces and in between a smaller representation of a tree. And finally, in Dier el-Bahri where the funerary temple of Hatshepsut, we have an offering scene where Hatshepsut is offering to Amun together with her daughter Neferure. And underneath the offering scene, as in the banquet scene, we have a representation of a huge garden with lettuces, and small trees, and ... as you see in this scene.

Now, this is iconography representations, what about archeology? Do we have Egyptologists found before us other gardens? Well actually, very recently and it has not been published so you are lucky also. The French people, the French team, French Egyptian team excavated in Karnak in what is called the Middle Kingdom court. Right behind the Sancta santorum. This is the floor of the Middle Kingdom, contemporary to our garden. They put up one of the stone slabs to find a garden underneath. So originally there was a big garden to provide the God Amun with offerings. But this was about 2000 BC, slightly later in the second cataract, in a fortress called Mirgissa, there is a settlement. And in that settlement, the French mission in the 50s, they discover a wonderful huge garden. Unfortunately they didn't, they were not able to retrieve any botanical remains. But the, the documentation is very interesting and as you can see there is a little path going through the garden. So when the garden was slightly elevated from the ground, they will use the staircase to get to the center. But when the garden was flat they will use these little paths to get closer to the central squares. And outside of this large gardens, the French mission discovered a house, and next to a house there was a little garden exactly the same as we have. That is why this picture made me realize that we don't have, like, a model garden or a miniature garden but actually, what would have been a garden for a family or for an individual. We have here a house and a garden, three meters by two meters, two meters twenty, with the same separation between the humid plots and the surrounding wall as we have, exactly the same.

Now, going forward in time, we jump to the Delta and there is an excavation by the Austrian team from Vienna. And they found that this huge city, the City of Avaris, and among the temples and the houses they found traces of square gardens. But again, because of the humid area, they were not able to retrieve any botanical remains. A little bit different is in Amarna. Amarna was the capital of Akhenaten Nefertiti, years after Djehuty and of course much recent than our garden. At the very beginning of the 20th century, the excavations of the Egypt Exploration Society discovered this garden near the North Palace. And this other garden, which is impressive, in the main city. Again, they were documented but the squares were not excavated, so no botanical remains are known from here. And only recently, a wonderful archeologist based in Cambridge and the University of Cambridge, Barry Kemp, who was a teacher for many of us, he dug in what is called the Works Man Village, and he discovered gardens associated with the houses and with little chapels next to the houses. And in these gardens he has been able to retrieve botanical remains. And what is interesting is that they match very well what we have found. He has found, coriander. He has found this non sweet melon. He has even found the same flowers, [name not clear]. And even traces of tamarisk. And more important for us is that he has found also remains of flax. So everything suddenly comes together. So this is another garden that he found in what he calls Kom El-nana. And these are gardens, wonderful gardens, that were next to a pavilion that Nefertiti built. Nefertiti had a little shrine there, and on both sides she had two gardens that were sunk like this, to be protected from the wind. And this is just, this is the last garden that I will show you in an island in Nubia called Amara West. And a British team also found these wonderful gardens, but no botanical remains were found. And what is interesting is that as in the Amarna, they have a system to protect the garden from the wind. As the Amarna Gardens were sunk, and this had a brick mud brick wall to protect the gardens from the northern wind, which is the predominant wind in Egypt.

Now, going back to our tomb, or to our site. Our garden, different from the ones that I have shown you before is not a daily life garden, but it's a garden built in the necropolis associated with a tomb. So it's a funerary garden. It has some features in common. It is also protected from the northern wind, and it has the surrounding wall and etc.. But it's a funerary. What do we know about funerary gardens? Very quickly. How are we going in time? Very bad. Well, in this tomb near Luxor, near ancient Thebes, we have the site called El-kab. And in this wall representation we have this Shrine of Osiris, the king of the afterlife, Anubis, the god of the of the mummification, and next to them this little square grid garden, next to a pool with palm trees and sycamore trees and obelisks. So this is a landscape of the here after that the Egyptians imagine. In this other tomb, also recently discovered by our Egyptian colleagues, we have this same composition, the pond with the palm trees and a grid garden. And next to it, it's very interesting that we have pottery as we found around our garden. In this case is pottery that seems to be incense burners, to burn incense next to the garden.

If we go long in time, we have the tomb of Ineny who served under Hatshepsut. We have the same square garden, the pottery has been erased, but it's the same composition. So we will go quite fast. In this tomb, that is now been investigated by a Brazilian team, we have the same composition with the pottery stands and incense burners on top of it. So it goes well with our pottery. This other composition comes from El-kab and for many years this was taken as a representation of the senet game, because of the different colors of the pieces on top of it. But from our collection of examples it can be now argued that it's a grid garden with the pottery on top, as we find in the tomb of Rekhmire. We have the same composition with pottery on top, and actually it's not a board game, it’s not the senet game, which is represented like here. So it's similar but not exactly the same. So I will go quickly. Another kind of representation comes from the tomb of Amenemhab. There is a wooden shrine with a little garden in front of it, and this guy hacking it up in a ritual. And this same scene can be seen in the tomb of Rekhmire. So apparently there were little gardens, and next to shrines.

So this is our garden. And, before we found the garden in 2017, only another garden was found before. It was found by a team of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Conducted, directed by Winlock in 1929, 30. Winlock spent long, long periods of time in Egypt. And at this point he was tired, ready to go home. He discovered the garden at the very last minute. This is the garden at the entrance of the tomb. So he recorded it, but didn't pay much attention to it. So this is the drawing that Winlock did in 1929, and this is the photos that were taken. Unfortunately, the garden was left exposed and with wind it completely was washed away. So nowadays there is very little of that garden, just that stain in the courtyard and nothing can be retrieved. So our garden, for the time being, is the only square grid garden that has been documented and properly studied. In the future, if other people excavate outside I'm sure other gardens will be found. Very, very quickly, we still have time? Just very quickly, we excavated each square garden, and actually with David and Jamal, we retrieve botanical remains. But we did only half of the squares so that a half will be preserved for future generations. That will be, for sure, much smarter than we are. So we only dug half of each square like this. And, but in each square we've found the seeds that were planted 4000 years ago. In this case we have coriander that today is used in the kitchen, but also in ancient times. And, as you see, the seeds and the plant remains got desiccated, and so are wonderfully preserved. So these are the Ark botanists in charge of the study, Leonora and [unclear name]. And this is the ancient coriander seed and how the plant looks like. Another plant that we found is [unknown spelling], a non-sweet melon that the Amarna, that Barry Kemp found in Amarna. But we also have it here in the year 2000 BC. And the flowers, we have the flowers from the Daisy family Barry Kemp found also. What is amazing is that these botanical remains, 4000 years old, have been so well preserved.

Why do we have this combination of vegetables and flowers? Because actually, that's what the owner of the tomb was expecting. In the offering tables, you will find bread, you find beef, you found fowl and you find vegetables, fruits and flowers. Why flowers? Because the flowers for the Egyptians had the potential of dying and be born again with the first rays of light. And also there is a word pun between the word for flower, which is ankh, which also means life. So when you offer flowers to someone, from the Egyptian point of view, you are offering them life. That's why the Egyptians farewelled the deceased with flowers, as we do today, because for them it was a way away to wish the dead life.

I am almost ready. We are lucky because around the garden, our garden, is a special garden. It's a funerary garden. What makes it different from the other gardens? The pottery. The pottery we found around the garden. The pots that were found, that were used in the rituals to say goodbye to the deceased. So we have these vases, that is called hes vase, to make libations. We have this other jar, these wonderful carotenoid vessels that are very interesting, and beer jars that were also used in the rituals. So the pottery is what makes this garden a funerary garden. In one of the corners we found an upside down bowl that when we turn it over, we found five dates in an amazing condition, 4000 years old.

And this is a drawing of the re-creation of how the garden would have looked like, with the plants growing in each square, the tree and the pottery being used in the rituals. And now, just one minute more. And how come this garden has been preserved, being so fragile, made of mud and mud brick? And the answer, we find it around the garden in the sand that has gradually accumulated on top of the courtyard. The lower levels are made of very, very thin sand that was blown inside the courtyard by windstorms. And it's actually this sand that eventually covered the garden, protected. So then when this part of the necropolis was used later on or reused by other people, like the mummies that I showed you at the very beginning, the garden was covered, hidden and protected.

And in this cut, near the garden, not only we find the answer to why the garden has been so well preserved but we are able, with geologists, to retrieve traces from rainfalls. We can have from here an idea of how many rains happened between the year 2000 and the year 1500 BC. And this is what the geologists are doing here, taking samples. But not only that, with a specialist in pollen, we are able to retrieve pollen from the sand. And so we can get an idea of the plants that were growing spontaneously or being cultivated near the necropolis. So from the garden we know the plants that had a religious meaning, and were used by human beings. From the pollen we can reconstruct the environment of ancient Thebes in the year 2000 BC, until the year 1500 B.C. This is Acacia, cereal, etc. And I think with this last slide, I close my talk. Thank you very much.

MC: Okay, we probably got time for 2 or 3 very speedy questions. I'm sure you agree with me that it was worth the wait. So any one got a quick question?

Audience Question: Hi. Thanks for a fabulous talk. I noticed that in the scenes from wall paintings from El-kab there were mood dances in the scene, and they were not right next to the garden but in the same scene, which as I understand it we’re still trying to work out what they mean. Might they have anything to do with gardens? JG: Well, the, the mood dancers where, some, where a group of ritual dancers that will welcome the deceased into the necropolis and will show the deceased, him or her, his or her destiny underground. That's why sometimes they are pointing down. The Egyptians mixed together the representation of the necropolis and going to the tomb and going to the netherworld, to the underground. So you have an invented or re-creation of the sacred landscape of the necropolis, but at the same time, what was going on of the hereafter and what was going on in the necropolis. So the mood dancers probably perform a dance in real life when the deceased approached the tomb. But the great garden was part of the landscape, with a big pond and the palm trees, that the Egyptians imagine that that was the entrance to the afterlife.

Yes.

Audience Question: The pottery, where did it went? Did it went to the museums in around Luxor or where will it go? JG: Well, we inaugurated the tombs of Djehuty and Hery. We opened them to the public in the year, well two years ago. And at the same time, we made a smaller exhibition in Luxor Museum at the other side of the river with the most significant findings. Of course, the garden has not traveled to the other side of the river. And the pottery, we tend to keep it inside our site. Sometimes we are asked to move it to the magazine, that the Ministry of Antiquities has nearby, near Carter House. But pottery is not important, depending on who, in whose opinion? So we can keep the pottery without any problem in our site. So we still have it with us. And it's, it's already studied. We are preparing now the publication that will eventually appear, published by the British Museum. The different authors of the different chapters have to hand in their chapters before the end of the year and so... The pottery is a very, very important section on their publication. And at the beginning, for instance, I'm very close friend of the pottery experts, so I was telling them, please, this is not a book about pottery. Make a selection, otherwise we will not see the garden. But actually I realized that it's the pottery that made the garden a funerary garden and a ritual garden, different from the Amarna Gardens and the other one. So the pottery should have, like, a predominant role in the publication. And it's a wonderful pottery.

Audience Question: When will yours be finished?

JG: Yeah, yeah, well I have finished, I have finished the chapter. That's why I have been looking for parallels. This is the introductory chapter. The introductory chapter has 80 pictures and I wrote about 30 pages. But then there is a chapter about the garden itself, the geology and the environmental information, the pollen, the botanical remains, the pottery. So it's going to be quite a complete volume. Yeah, it will be finished. No, actually, we plan to finish it two years ago so we hope to finish it this year. This year should be.

MC: Like any good group project always gets extended. Okay, I'm sorry, we're really going to have.... Oh, okay.

JG: Be kind with me.

Audience Question: What was the pottery useful?

JG: The pottery. Well, the pottery for the ancient Egyptians was very important because it was the way they had to store things and to carry things. So if you want to bring water to the garden, you will use pots. But if you if your mother has made an excellent duck, with cucumbers, etc., then you will have a jar to store the leftovers. Or you can use the jar also to have wine inside or beer, which was also very common.

So pottery, it was very, very important in a daily life, but also in the ritual religious activities of the ancient Egyptians. That is why in the excavations we find so much, and for us is also very important because the pottery changes a lot with time. There are fashions. In one period you will find globular pots, but then you will have like bottles. And for us it's important because through the pottery we can have a quick idea about the time period we are dealing with. So you have [unknown name] pots and I know the garden is 2000 BC. Of course you can then do analysis to check and do carbon 14 to prove you are right. But most of the Egyptologists, thanks to the pottery, we don't need so much carbon 14 as in other places, because through the pottery we know the time period, because of the fashion of the pottery. MC: Thank you so much. Apologies for cutting questions short but we are limited in time, but I'm sure you will agree and join me once again in thanking Doctor Galan for an amazing talk.

[Recording] Thanks for listening to the talks archive brought to you by the Western Australian Museum Boola Bardip. To listen to other episodes, go to visit.museum.wa.gov.au/episodes/conversation where you can hear a range of talks and conversations. The talks archive is recorded on Whadjuk Nyoongar Boodjar. The Western Australian Museum acknowledges and respects the traditional owners of their ancestral lands, waters and skies.

More Episodes

Gender-related violence isn’t talked about often enough, but it happens in WA. Often, conversations centre on victims and perpetrators, warning signs and cycles, breaking points and crises. But what happens next? How do we move toward recovery, reconciliation, and positive change?

We know ferns have existed on Earth for millions of years, but just how closely do ancient ferns resemble modern ones?

By drawing on First Nations knowledge systems, cultural practices, and research methods, this presentation will showcase how climate adaptation and mitigation strategies that respect and integrate Indigenous knowledges and practices can help sustain well being.

Have you ever wondered what it is like working with fossils every day? Helen Ryan from the WA Museum shares her work in discovering, uncovering, preparing and preserving ancient life.

Hear from Dr Amanda Ash from Murdoch University’s School of Medical, Molecular and Forensic Sciences as she delves into the complexity of parasites and their importance.

Curious about the creators behind our Megalodon head in the Wild Life gallery? Join the makers from CDM: Studio and peek behind the scenes as they share their process of designing, building and delivering museum exhibits.

Discover what we can observe about the Moon, learn about our current knowledge, and understand the importance of returning to its surface!

Discover the elusive Night Parrot at WA Museum Boola Bardip! Join us for an exclusive panel discussion with experts Penny Olsen, Allan Burbidge and Rob Davis.

Join Museum experts Jake Newman-Martin and Linette Umbrello as they take us on a mammalian adventure of the minute kind, from tiny marsupials to giant megafauna.

Discover the remarkable story of Wayne Bergmann, a Nyikina man and Kimberley leader who has dedicated his life to his community, in this moving memoir of living between two cultures.

Celebrate Perth Design Week with a robust panel discussion focusing on design and business.

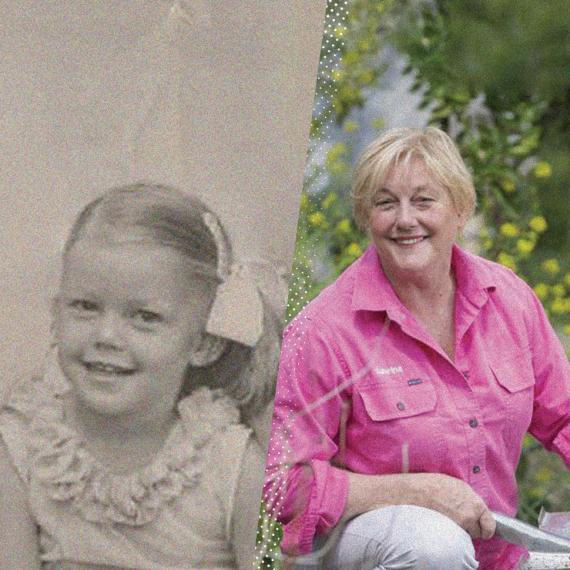

Talk series hosted by Geoff Hutchison that explores who our young selves were and what became of them. This week hear from Sabrina Hahn.

Navigating the delicate balance between the preservation of the Conservation Estate and our cherished and loyal feline companions is both a challenge and a responsibility.

How much will we look to the language of activism in finding the way towards reconciliation in Australia?