Eclipse Chasers: Past, Present and Future

Experiencing a total solar eclipse is unique and exhilarating, involving anticipation, planning, adventure and a sense of humanity as part of nature in our special solar system. Join historian Toner Stevenson and astronomer Melissa Hulbert, to hear about the April 2023 eclipse; discuss how to prepare, what to expect, and what to notice with eclipses, and the science of eclipses.

Both experts also discussed their contribution to the 'Eclipse Chasers' book, focusing on the April eclipse.

Published by CSIRO, the 'Eclipse Chasers' book is about uniquely Australian eclipses, beginning with First Nations experiences.

The opportunity to study the Sun, our closest star, and test Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity has inspired astronomers to also experience the challenges of distance on land and sea in Australia. Some of their challenges, scientific ambitions and results of past expeditions detailed in the book will be discussed. For First Nations Peoples observations of total solar eclipses hold cultural, historical and scientific meaning.

"Eclipse Chasers is an intriguing book about eclipses providing great insight to what an eclipse is as well as tips on how to become an eclipse chaser. What this book does is remind the read that there is much more to what’s happening in the skies above, it’s asking you to be aware of your surroundings, the stillness, the darkness, and the chance to see 'the diamond ring' in the sky." Deanne Fitzgerald, Western Australian Museum, 11 October 2022

Have you ever wondered how scientists can calculate the exact dates of an eclipse?

Visit our temporary exhibit Reconstructing the Antikythera Mechanism. This exhibition delves into an intricate device created in ancient Greece around 200 BCE—the Antikythera Mechanism, also known as the world’s first mechanical computer. Its estimated 69 gears performed complex mathematical calculations to predict the location of the sun, moon, and planets. View a working replica of the mechanism and learn more about the extraordinary story—from its chance discovery in a shipwreck to the modern scanning technology that enabled a replica to be made.

-

Episode transcript

DF: Good afternoon, everyone and welcome to the WA Museum Boola Bardip. My name is Deanne Fitzgerald, and I'm the senior Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Advisor here at the WA Museum. We’re welcoming you here to talk about Eclipse Chasers; past, present and future. Before we begin, as we always do here at the museum, I'd like to acknowledge that we're meeting on Whadjuk Noongar land and I would like to pay my respects to elders past and present, and to acknowledge any First Nations people in the room today.

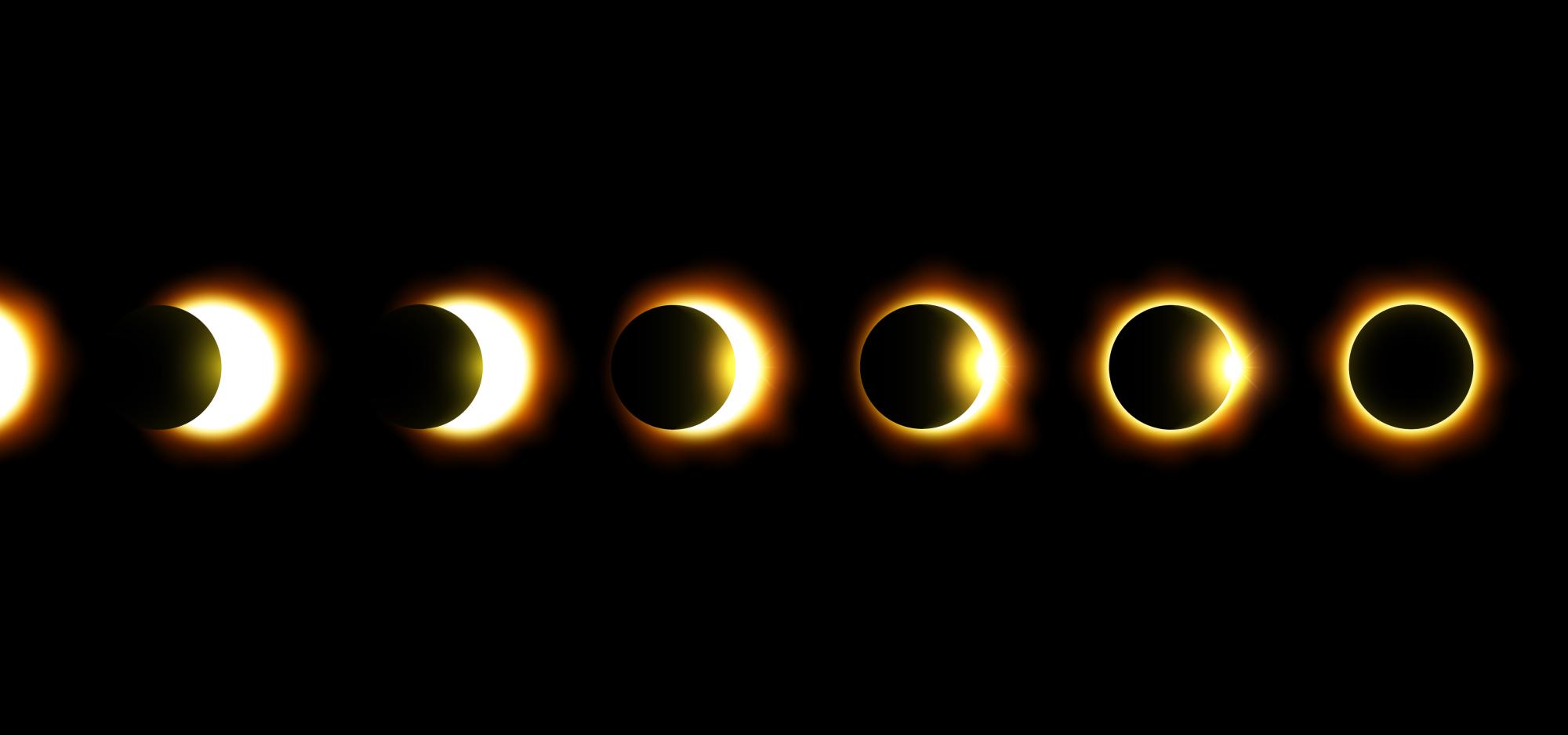

Eclipse; It's a natural phenomenon where the moon passes between the sun and Earth, blocking the sun's light from Earth. I googled it today (laughs), I knew that. I do remember an eclipse, I am older than I look. It was back in 1976, there was an eclipse happening. I can’t remember where it was, but I do remember as a primary school kid, it was a school day. Our teachers were preparing us for the day and we were told, “do not look at the sun, you will go blind! The sun will burn your eyes!”. So here I am, this little six year old kid, this fear of this thing happening, and this fear of going blind, having no idea what to expect. We made the pin view pieces of paper. The two pieces of paper that you get with a pin in the top, and one underneath, here we are making the holes. “Oh, so we look at the sun through the hole?” “No, you're going to go blind!”. We went outside not knowing what was going to happen. Here I am with my pieces of paper looking at the shadow, moving across my paper, and I'm like, “How is this working? Is it a trick? I don't believe what's actually happening!”. Then suddenly things started getting a little bit dark, so I closed my eyes because I didn't want to go blind. Now I wear glasses, so anyway!

Eclipse Chasers is an intriguing book about the eclipse, providing a great insight to what an eclipse is about, as well as tips on how to become eclipse chasers. What this book does is remind the reader that there is much more to what's happening in the skies above. It’s asking you to be aware of your surroundings, the stillness, the darkness, and the chance to see the diamond ring in the sky as shown on the book. Next Thursday, the 20th of April, all eyes are going to be on Western Australia, in particular Exmouth as the eclipse happens. Two eclipse chasers will be there; Dr. Toner Stevenson and astronomer Melissa Hulbert. Today they're here to talk about this amazing book, Eclipse Chasers, which I think some of you have bought and Toner has signed. So please welcome Toner and Melissa.

TS: Thank you for that wonderful introduction. I want to acknowledge First Nations people as the first astronomers and the creators of historical observations which connect land, sea, sky with the whole cosmos. Deanne Fitzgerald, thank you very much for that lovely introduction and your own personal experience, because that's what it comes down to with eclipse chasing. It's about how we feel in our position on this planet, in this solar system, in this cosmos.

Deanne reviewed our book and we definitely appreciate that. We were not sure how keen people would be about a book that was about Australia, uniquely about Australia, and about the past, as well as the eclipses coming up. I'm very happy to say we've had some good reports and I hope those who've bought the book today and read it will feel the same way.

This is a wonderful museum, and I can't even talk about the book until I talk about this museum, because this museum is a world leader and you're very, very lucky. If you're from Perth or Western Australia you’re very fortunate to have this wonderful museum and its collection and the way it's been interpreted here. It is up there, it is actually beyond most other museums on this planet. I was very lucky today to see the Antikithera exhibition. If you haven't seen that, I believe it's on for some time.

I'll now go to the book. The book begins with a snapshot of the past, and the Antikithera mechanism by the Greeks was one of the very first mechanical methods of predicting eclipses. Now, this was back, 60 years before the common era. You know, this is a long time ago. In those days, eclipses were very, very powerful. In the book, I talk about the way that Roman emperors had their coins imprinted with an eclipse on one side. In fact, one Roman emperor said that when he died, he didn't want to be buried until there was a total solar eclipse. They really align power with this astronomical phenomenon, and there aren't many other phenomena like that. In fact, it is unique.

The book came about through a collaboration, and I really want to acknowledge the people who contributed to the book. Dr. Nick Lomb, who was curator of Sydney Observatory for 30 years. Nick wrote the Australasian Sky Guide and still does. He is a source of a lot of knowledge and if you go on to the Astronomical Society of Australia's website about this eclipse, what you read there was written by Dr. Nick Lomb. He's also a historian, and deeply embedded within the world of how astronomy has developed over the years and progressed our knowledge of who we are and where we are.

Duane Hamacher! Duane is an expert on First Nations astronomy, but he's approached this subject very differently to a lot of previous people, in that he gives First Nations people their own voice and helps them extend their voice when they want to. Now, this has been ground-breaking, and you'll find in the book that his work and the work of Uncle Gila, Michael Anderson, some of these stories are being told for the first time. There's been a change in how the knowledge of Aboriginal people is being conveyed and this knowledge is so important to our whole understanding of our country, of the history that's gone before colonization, and how Western science is not the only science.

Melissa Hulbert, you're going to hear from Melissa soon. She's an Astro-photographer and astronomer. Jeff Wyatt is an astronomy educator at Sydney Observatory, and Kirsten Banks is just about to hand in her Ph.D. She's a young Wiradjuri woman who is going to be one of Australia's leading astrophysicists in the future. She actually concludes the book, with the scientific ‘what to expect’ with these future eclipses. I want to acknowledge CSIRO Publishing who are just amazing to work with.

We live in an amazing solar system and we should not forget that. There's a lot of research that's being done. Those that have been following astronomy for the last 30 years, would’ve seen the incredible explosion of information about other planets, other solar systems. So far we haven't found any other place like ours. A planet where the sun, its star and the moon perfectly align with a planet like the Earth. We are very lucky to be in this unique position.

Before we go too much further, we're going to try and demonstrate what happens during a solar eclipse. I'm going to ask Melissa to come and help me do this, and we're going to need some people from the audience. So if Deanne is still there, she might come up, and could I get two more people? Two more volunteers to come up and help us? Deanne, you can be the Earth. Peter, you can be the moon. I need a sun? You’re going to be the sun. Now, this is not going to work perfectly, because the scale is so far out, but if you can shine your sun on the moon. can you shine your sun? You have to be in the perfect line. Okay, that's it. There we go. So I'm hoping the audience can see that there is a shadow of the moon on the planet Earth, and here is our sun shining brightly. Now, it would be lovely if during total solar eclipses, the shadow was that wide, but Mel can you tell us a little bit about that shadow, please?

MH: All right. So as Deanne said earlier, it's a three body alignment which we call a Syzygy. Essentially, the sun's diameter is 400 times greater than that of the moon, but a little quirk of nature means that the sun is 400 times further away. During an eclipse, what we see is the sun and the moon both have the same angular diameter in the sky, about half a degree, so they perfectly overlap. This combination gives us a total solar eclipse. Now, the shadow itself, you can see in the image behind us.

TS: [Toner asks audience volunteers to demonstrate] Mike, if you were 400 times away, we would be sending you a very long way away. But we're not going to do that, just enough so our audience can see the image behind you, thank you.

MH: The conical shadow that you can see there is on average about 480 kilometers across. The darker part, which we call the Umbral Shadow, is on average only 160 kilometers across. You need to be under that part of the shadow to see totality. If you're not there, you don't see totality. If you're here, you get a partial eclipse, which will be here in Perth. If you're outside of that, you see nothing. So that's how a solar eclipse casts.

TS: Thanks Mel. If you're traveling up to Exmouth, or around that area, the path of the umbra is very narrow. It's only 40 kilometres across, and the pathway can be up to 250 kilometres across. It’s so important to be in the right space at the right time. Now, I'm going to give you just a little snapshot of some of the past historic events that have happened here in WA, because WA is very important in the history of eclipses.

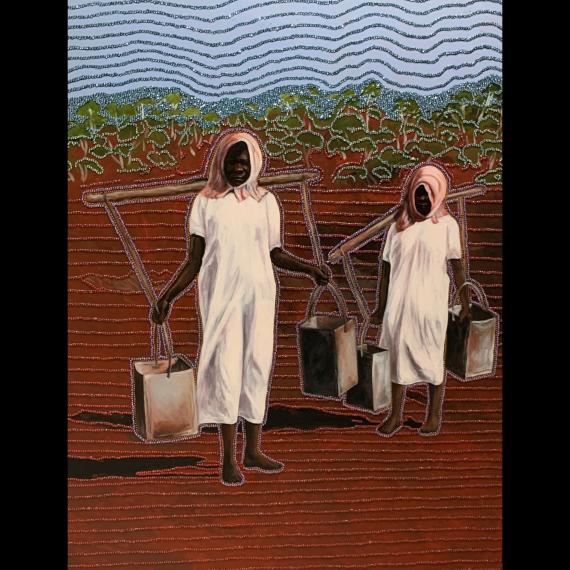

Before I do that, I do want to acknowledge First Nations people and their knowledge. It's only through the Nyangumarta and Warrarn people, who have helped and given permission for some of the stories to do with the eclipse in 1922, that I'm going to tell you. This is a drawing by David Bosun who's actually from Moa Island up near the Torres Strait. There's a lot of eclipse stories in the book that relate to that area as well.

So, let's go back 100 years, 1922. Things were very different. There was a very magnificent eclipse coming up and it was very important because of Einstein's general theory of relativity. Now, what was that? That was about how massive objects can impact both diffraction of light and space itself. Einstein's theory of general relativity had kind of been proven in 1919 by the British, but it was only by using four or five stars that they were able to show this diffraction of light that happened around the sun during an eclipse, from the stars that had been photographed before there was an eclipse and then during the eclipse. It's a little hard to describe, but I think you'll get the gist of it when I’ve finished. So there was a big eclipse coming up right across Australia. You can see that Wallal in WA was in the very best place, that was where the eclipse was going to be long, almost 5 minutes! Amazing. Our eclipse coming up next week is 61 seconds.

This is what they were trying to prove, that the curvature of space is due to massive objects causing a distortion in space time. A very elusive concept in those times. It had not been possible to do that, until photography had been perfected and that had taken some time. It was also about having the right sort of team of people there to work on this problem. 1919 was just at the end of the First World War. There were problems with trade routes. They didn't have much financial support and no new equipment. By 1922, Lick Observatory in California had managed to work with Yale University and other observatories to develop new equipment. We also had the inclusion of some very smart women who were behind the organisation of sending a large group of international people over to Western Australia. This was not a simple feat; they were gone for months, the conditions were not that well known. They had to bring tents, what sort of food could they get? It was a big deal to organize this kind of expedition. They also had great financial support from a fellow called Crocker, and support from the Australian Navy. Here they are on the Australian supported Navy ship on their way from Broome to Wallal.

They also engaged almost 40 Nyangumarta Warrarn men and women to help them set up the eclipse camp. The local knowledge of these people helped make the eclipse a great success. It was very hot at this time, and you can see this amazing photograph showing young Aboriginal women leading the donkeys. They had tons and tons of equipment. The boats were out there in very shallow water.

They were carrying equipment in, bringing it in on small boats. It was an incredible feat. Setting up the Eclipse camp, they used jarrah timbers. There are a lot of flies, so they had nets over their heads. They couldn't really eat until the sun set because that's when the flies were not as prevalent. You can see this amazing equipment, this ship, early camera, 40 foot or 12 meter telescopic camera. The whole thing was photographed by a New Zealander called Ernest Brendan Kramer and in your State Library you have the most amazing photographs from this eclipse expedition.

The women didn't just help organize it, they also performed work on the instruments with the men. They were all in partnership and this was a really big team effort. You can see here Elizabeth Campbell, one of the astronomers, and they're positioning a telescope on the very large moving arm that's holding a lot of instruments. They were doing spectroscopy, which means that they were taking photographs of the corona of the sun and testing its chemical composition. They were also trying to photograph these stars around the eclipsing sun to test Einstein's theory.

This is Mary Orr with her husband John Evershed, she was Mary Evershed by then. This woman had been to Australia before. She was here between 1890 and 1895. She wrote the first Easy Guide to the Southern Stars, which was published for 40 years later and was a lovely little handbook. She was also by then, a solar physicist. Her and her husband ran the Kodaikanal Observatory in India. You can see them adjusting this instrument that's called the sealastat. It's a very large mirror and it moves. You can move it, rather than move a telescope, so it was actually very good for a very stable photographic piece of work.

The whole world was waiting to hear what happened. I'm sure many of you will know about Charles Kingsford Smith. He was a very young man there, and Norman Brearley, and this is one of their very early adventures across the country bringing back bringing the news. He, of course, was passionate about seeing this amazing eclipse, and being on the site with this international group. His job was to take back the news of whether it was successful or not.

You get an idea of what the landscape was like too from this image. Wallal Downs was a harsh landscape, a hot landscape. I noticed some Perth Observatory people here (in the audience). They were very involved, they had their own camp. They were very important in actually helping and taking their own observations. They weren't doing so much the Einstein testing, but were looking more at spectroscopy. They were looking at the corona, they were measuring the temperature. Their primary contribution to testing Einstein’s theory was providing the exact timing, and this was not easy. I find it incredible that they were receiving wireless signals at Wallal from Bordeaux in France in 1922.

This is, in my mind, is the most amazing photograph where you can see the kind of kit and set up that they had. In the very rudimentary shed, you can see bales of wool. It's a very interesting set up for a very precise operation. You can see Clive Nossiter on the left. He was the assistant astronomer at that stage to Kerlewis, and Vincent Matthews, who was actually the headmaster in one of the high schools here in Perth. He was a very adventurous, very knowledgeable person in his own right.

These are some of the drawings that the group did. They took photographs, but this was a long eclipse, so they had time to draw. You won’t have time to draw if you're coming to the one next week, but, you know, it's a really good thing to do when you're at an eclipse because it really trains your eye on what to look for.

This is one of their photographs in the left corner. In the end, Lick Observatory did it, and their special equipment paid off. You can see one of their plates where they've circled the stars that they're going to use for the Einstein experiment. William Campbell was the leader, and it's a lovely photograph of him trying to adjust these large plate holders. They were the only ones that had this. They did give some plates to the South Australian Observatory at Cordillo Downs, but they definitely had the leg up on the kit, and how to use it. This is one of their drawings, showing the diffraction of the images of the stars. They proved without doubt that Einstein's general theory of relativity was in fact true, and after that, Harold Spencer, who was the assistant astronomer at Greenwich, said, “Look, we're not going to try and do these things next time. It was really such a big deal to get this result, that there was no sense that it was worth repeating. It had already been proven.

I'll just quickly touch on the 1974 eclipse. Is there anyone here that experienced the 1974 eclipse? The center line of totality actually didn't touch land, just the top northern limit of the line. These are some eclipse adventurers, they’re from Williams University in the US. The gentleman on your right, Jay Pasachoff passed away just before Christmas. He had seen more total solar eclipses than anyone else on this planet. Here he is in W.A. as a very young man with his wife Naomi and one of their students, with quite an extraordinary piece of equipment. Unfortunately, it was cloudy and there’s a very nice story told in the book about it. They did have a plane ready, and they went out in the plane, a small plane. I think they had some success there.

The people that had the most success were the people who’d asked Ansett (airlines) to help take them up and follow the eclipse. They were real eclipse chasers. That was a group of amateur astronomers from Victoria and they got some lovely photographs. There is one there that you can see the diamond ring.

So back to now, I'm going to hand over to Mel, who's going to talk about what's coming up and why it's exciting. Thank you.

MH: Next Thursday we have a total solar eclipse, but it’s a really special type of eclipse that's happening next week. It's what we call a hybrid eclipse. At the start of its track, off in the Indian Ocean, it's an annular eclipse and then it progresses to a total and then at the end of the track, it's an annular eclipse again. This is what we call a hybrid. An annular eclipse occurs when the moon is slightly further away from Earth in its orbit. It's smaller and doesn't completely cover the sun, and you get the ring of the sun around the moon. This eclipse will be very, very interesting and very rare. Only seven out of 224 eclipses this century will be a hybrid eclipse.

This one is passing over quite a narrow track of land, actually, the path is only 40 kilometers wide, so very small. As long as you're between the southern and the northern limits, you will see totality. If you're along the centerline, you get a longer eclipse. That’s why a lot of people tend to head towards the centerline. If you're out near the northern or southern limits, you see more of what we call Baily’s beads, the little bright spots from the craters on the edge of the moon. So there's advantages to being in either place. The prospects are pretty good for Australia and Exmouth. You can see that the cloud we want to see is blue, this means less cloud cover. We're in a prime observing position, hopefully.

Safety is also super important with eclipses. You need to wear glasses when you're looking at partial phases, and even during an annular eclipse, you still need to wear glasses. Use eclipse glasses or have solar filters on your telescope or camera lenses, and make sure they're certified. During totality though, you need to take your glasses off so that you can see the full spectacle that is totality. You can use a variety of homemade projections. Somebody has got a cup here and is projecting onto a plate. This is a pinhole version and this is what a solar filter looks like when you're taking the partial phases. In fact, I think we might have an example of a pinhole.

TS: This is what I've been doing in my spare time. You can come up and have a look later on. I've just used a very thick pin and I’ve drawn a sign on a piece of cardboard and just use the very thick pin. I’m going to hold that against a white piece and do a nice little projection. You can do all sorts of fun things. You can even use your hands, cross your hands like this and do projection through and you'll get, you know, you can change how big the holes are and and all of that. You'll get some really nice projections on the ground or on the white sheet of the partial phases, its a lot of fun to do that.

Notice your shadow. When it's not during an eclipse and the sun shines onto your hand, it still looks like your hand. However, during an eclipse as it gets more and more into the eclipse, your fingers seem to grow. It's really strange and certainly worth noticing.

MH: So eclipse glasses, usually they're certified on the inside of the glasses and you just wear them as you would a normal pair of glasses. Never ever look through your camera or your telescope without a proper solar filter, either. It will cause damage to the sensor as well. So always use solar filters. Totality you can watch with your eye, and the diamond ring once it starts. We’ll get about 62 seconds if you're close to the center line for this coming eclipse.

What is totality like? Well, think of somewhere you'd like to see an eclipse from. Imagine the moon's shadows racing towards you at 3683 kilometres an hour. A slight breeze starts to blow and the atmosphere cools. You get this beautiful golden light that you never see any other time on earth. The birds start to roost, and then the diamond ring heralds the start of totality. The sun's corona is like a pearly halo surrounding the dark disk, and the prominences are like little fingers of flame coming off the edge of that dark disk. Stars, planets, constellations are visible. Then the second stunning diamond ring heralds the end of totality and we're plunged back into a world of light again. A total solar eclipse is perhaps one of the most awe inspiring, immersive, natural wonders on Earth. We get to see it pretty much for free. Okay, we've got to travel a little bit, but it's definitely worth it!

This is what the sky will look like at totality. You will be able to see Jupiter because it'll be nice and close to the sun when you're looking at totality. Saturn will be a little further away and then Mercury and Venus quite low. You may or may not see all of them. As I said, there's a lot to take in during totality. That's one of the reasons why we go to multiple totalities to experience that, and there's five eclipses coming up. I'm going to pass back to Toner.

TS: We’re nearly finished our talk and we wanted to leave it with some hope. Who knows? It might be cloudy, but don't worry, there's more coming up! You can see that WA is in a really nice position here for quite a few eclipses. 2037 we've got this nice one coming down through here. You’re going to be very well positioned and we're very fortunate in Australia to have this happening.

I want to finish up by thanking very much the WA Museum, particularly Ruth Morris, who's been with us all the way and organized this great event. I want to thank Jesse over here who’s been doing the technology. I want to thank all the visitor services operators because I know they’ve really busy today telling people where they can buy their eclipse glasses. Also the shop staff, because I think they've been run off their feet. For those that couldn't get their eclipse glasses today, I've heard that they'll have another shipment coming in two days. So don't despair, but don't leave it too long till the last minute!

Can someone tell me if Perth Observatory have eclipse glasses? Thank you very much. That's important to know because it is most important that you do have those correct glasses to use. I want to also thank you all for coming tonight and I hope you all have a fabulous eclipse experience. I was upset to hear that Deanne won't be here for the eclipse this time, but Deanne we're going to make sure you get to see the next one. Thank you very much for your hospitality and your museum's hospitality. Thank you. Any questions?

Audience Member: If we’re staying in town, in Perth were would you recommend would be a good place to go? A big open field, like a sports field or?

TS: Yes, I think it'd be about 43 degrees above the horizon. So when it goes into partial, you'll see a partial phase, about 77% we think, that's still reasonably high. As long as you’re not under trees or have big buildings, an open field is always a good idea. Make sure you have plenty of U.V. protection though, your sun hat and all of that, because you can forget about all of that when you're so engrossed in the eclipse.

Audience Member: What time of day is it?

TS: Here in Perth, 11 a.m. It’s a little earlier up North, so 10:04am, that's when it starts. We've got some more accurate timings coming up.

Audience Member: I want to let everyone know there will be some telescopes up in the museum next Thursday

TS: There will!

Audience Member: I know two of them are coming from the Perth Observatory so I might be there

TS: That’s great! What’s your name?

Audience Member: Lexi

TS: So come and see Lexi if you're in Perth. It’s from ten till three, is that correct? Do you have to book? You don't have to book. So turn up. I'm sure it'll be a great day. Fantastic. Any other questions?

Audience Member: Is there a train up to Exmouth?

TS: Unfortunately, there's not a train. There's a plane. There's an airport there. You might have to see if you can hire a car or something. I don't know. Sorry about that. I couldn't help you with that question.

You could start looking just after 10 a.m. and you'll just see the moon shadow take a bite out of the sun, and then you'll see between 74 to 77%. I've read both those amounts.

Audience Member: Can you explain the moon relevant to the eclipse?

MH: The Moon is actually tidally locked, so we always see the same side of the moon, always the same face. We see the same side always, the same the inside of my hand as it goes around. So When Earth’s sun is behind us we're still seeing the same face, but none of it's lit because its directly covering the sun. So the moon is always black. The moon will appear dark during the eclipse. It's not going to be lit. Think of moon phases, we get moon phases every month. A lunar eclipse occurs during a full moon. During a new moon we get a solar eclipse. Now we don't get one every month and that's because the moon's orbit is actually tilted by about five degrees. That movement means we don't see it every month. If it was perfectly aligned, every full moon would be a lunar eclipse and every new moon would be a solar eclipse. The dark side of the moon stays the dark side of the moon an we don't see it.

TS: I also want to show you something else that's kind of fun, too. After seeing totality you might like to have prepared a black sheet of paper with some circles on it. What I'm going to do, I've got a nice white pen, after the eclipse I'm going to try and draw my visual memory of the diamond ring of totality and then the diamond ring leaving the eclipse. I hope that you've got a few ideas of how you might spend April the 20th, next week, during either a partial or total phase of the eclipse. Thanks for coming tonight.

Applause

More Episodes

A compelling discussion shedding light on the distinctive narratives of those openly embracing their HIV-positive status and what this has meant historically and in today's world.

Meet Professor Kliti Grice, the West Australian Scientist of the Year 2022, as she embarks on a quest to decipher the Earth's past mysteries.

Join a panel of featured young LGBTQIA+ writers and storytellers as they delve into the fantastical realms and real-world struggles of the exciting new anthology, An Unexpected Party.

Explore Australia's dinosaur legacy with Dr Stephen Poropat as we better understand the science behind the scenes of Australian palaeontology!

As we inevitably move towards cleaner, more sustainable forms of energy, how will a shift away from traditional mining practices transform this economy? A panel of experts explore the implications of this shift with a specific focus on how we see ourselves in a world that increasingly demands environmental responsibility.

Join Megan Krakouer, a prominent Aboriginal leader, as she discusses the nuances of her surprising change of heart on the Voice to Parliament — just a week before the referendum.

Join host Michael Mills in a captivating live recording of the Palaeo Jam podcast during National Science Week!

As AI rapidly evolves, join our panel of experts in an exploration of these complex issues, including how we can harness its power while ensuring responsible and ethical use before we're outrun by its speed.

Do you know how and why your teeth do what they do? Find out all there is to know about teeth sharpening.

Decoding the language of our written and oral histories in Australia.

Join us for an insightful talk with the esteemed Professor Henry Skerritt, as he takes us on a journey exploring the captivating art of Jdewat/Ballandong artist Meeyakba Shane Pickett.

No, it’s not a card game but a community initiative helping us further our knowledge of a group of endemic land snails Bothriembryon affectionately called ‘Boths’.

Delve into the way Aboriginal industry professionals are shifting representations, decolonising the media space and creating visibility for Aboriginal people in the industry.

Exploring the debate surrounding the establishment of an independent, representative advisory body for First Nations people.

Aristeidis Voulgaris sharesstories from his eclipse chasing travels and discover the complex instruments and tools used in solar astronomy.

Join a panel of experts and community as they investigate the nature of queer bodies, and queer sexuality, in public space.

Simon Miraudo and Tristan Fidler from RTRFM’s ‘Movie Squad’ are joined by Chelsey O'Brien, Curator at ACMI, as they review and discuss Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland as a foundation for contemporary storytelling in film.

In this one-off Perth Design Week talk, the Museum celebrates the remarkable women in architecture and film in a panel discussion, recorded as a part of its recent award-winning film screening.

Join world expert Dr Chris Mah from the Smithsonian Institution as he recounts his encounters with some of the most unusual creatures on the planet.