In Conversation: New climate, new identity

How deeply entrenched is WA in its 'mining town' identity?

Western Australia has for a long time been intertwined with its mining industry, forming a symbiotic relationship that has shaped the economy and sociopolitical landscape.

As we inevitably move towards cleaner, more sustainable forms of energy, how will a shift away from traditional mining practices transform this economy? Will we have to re-evaluate our collective attitudes, societal priorities and aspirations?

A panel of experts explore the implications of this shift with a specific focus on how we see ourselves in a world that increasingly demands environmental responsibility.

Facilitator

Meri Fatin is a highly regarded interviewer, facilitator and podcaster specialising in finding the deeper story. Meri has been a guest curator of TEDxPerth COUNTDOWN: WA Climate Leadership Summit, is the founder of WA Climate Leaders, and was the curator of the 2021 In Conversation Series Tipping Point which featured a range of high profile speakers in discourse around various climate change issues.

Speakers

Since arriving in Australia Toby Price has held several leadership roles in emerging technology fields, developing a range of renewable energy projects across Australia and internationally. Toby has led the development of high renewables micro-grids for utility and private customers in both on-grid and off-grid applications. Since joining Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO), Toby has supported regulatory projects in WEM Reform and NEM 2025 before refocusing to WA Future System Design, seeking to map AEMO’s role in the energy transition and ensuring we have the tools and capability to manage 100% instantaneous renewables. Price has a background in academia where he developed novel solid state hydrogen storage materials at the University of Nottingham UK.

Adam Carrel is a Partner in Ernst & Young’s Climate Change and Sustainability Services team. Adam’s role is primarily related to addressing the challenges of sustainable development – how can the world sustain a decent standard of living for all current and future human beings in a way that doesn’t undermine the integrity and longevity of the biosphere. Adam frequently works on-site in remote locations and also provides advisory services to some of the world’s largest corporations. It also includes M&A advice and civil society engagement. He is a frequent TV and radio commentator on the subject and publishes opinions in this area as a part of the Antithesis Project team.

Heidi Mippy has worked in community development for over 22 years. She has extensive experience with Indigenous communities. Heidi is a small business owner and volunteers her time to several Boards and Advisory Groups in the community and was recognised as the 2020 Citizen of the Year for the City of Fremantle. Heidi holds a Bachelor of Arts in Community Management and Adult Education, a Graduate Certificate in Business (Leadership, Strategy & Innovation) and an Executive Masters, Leadership, Strategy, and Innovation. Heidi currently works with Noongar Land Enterprise Group, supporting Noongar landowners with land management and enterprise development. Heidi is Lead of Cultural Capability and Capacity Building within our Centre Executive, and co-leads the Socioeconomics Research Theme of the ARC Training Centre for Healing Country with Professor Fiona Halsam McKenzie.

Fabiana Tessele is one of the Steering Committee Members for Circular Economy WA (CEWA), a not-for-profit association built to catalyse the transition to a more Circular Economy in Western Australia. CEWA has been formed by an experienced steering committee made up of representatives from government, industry and others who are passionate and committed to progressing Circularity.

About In Conversation

A safe house for difficult discussions. In Conversation presents passionate and thought-provoking public dialogues that tackle big issues and difficult questions featuring diverse perspectives and experiences. Panelists invited to speak at In Conversation represent their own unique thoughts, opinions and experiences.

Held monthly at the WA Museum Boola Bardip, in 2023 In Conversation will take different forms such as facilitated panel discussions, deep dive Q&As, performance lectures, screenings and more, covering a broad range of topics and ideas. For these monthly events, the Museum collaborates with a dynamic variety of presenting partners, co-curators and speakers, with additional special events featuring throughout the year. Join us as we explore big concepts of challenging and contended natures, led by some of WA’s most brilliant minds.

Want to catch up? Listen to previous conversations now.

-

Episode transcript

In Conversation: New Climate, New Identity

Thursday 12th October

Facilitator: Meri Fatin

Speakers: Toby Price, Adam Carrel, Heidi Mippy, Fabiana Tessele

Welcome to In Conversation, a series brought to you by the Western Australian Museum, Boola Bardip. In conversation is a safe house for difficult conversations and passionate and thought provoking public dialogs that tackle big issues and difficult questions. Led by some of WA's most brilliant minds in Conversation is recorded on Whadjuk Nyoongar Boodjar The Western Australian Museum acknowledges and respects the traditional owners of their ancestral lands, waters and skies.

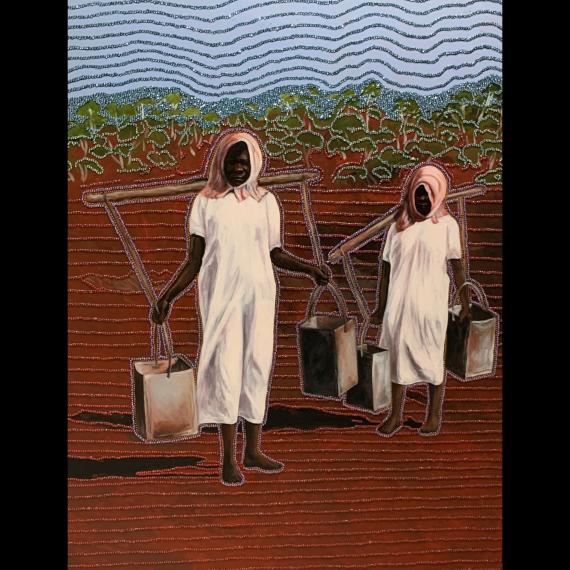

MF: Now you can hear me. I acknowledge the privilege of living and working and gathering on the unceded lands of the Whadjuk people of the Nyoongar nation. Of course, this country was never ceded and Nyoongar is of course a part of the oldest continuous culture on earth. They have been the spiritual and cultural custodians of this country for tens of thousands of years.

I'd like to pay respect to elders past and present upon whose knowledge we will be relying heavily to restore boodjar for the sake of all living things over coming years. I'd like to pay a special respect to all Aboriginal people in the room, and particularly to our panelist, who is Nyoongar Thiin- Mah-Warriyangka Yamatji Yorga Heidi Mippy.

Heidi, would you like to add anything to my acknowledgment of country before we begin?

HM: I thank you very much. I think it's just nice to add a thank you for doing that acknowledgment. I like to acknowledge that are a matriarchal country, a Nyoongar country and where we sit here, I like to acknowledge Woomal is a wonderful matriarch of our people. And we are very close to the paths that she walked. And I like to acknowledge her because it's quite relevant to what we talk about, our topic tonight. She is someone who resisted the slaughtering of colony, but in particular around sustainability of our bush plants and medicines, and the protection of these areas around Swan River and where we are sitting now. So I just thought I'd make special mention of her for you.

MF:Thanks, Heidi. So just to introduce this conversation tonight, it's been a really big realization for me over the last couple of years that we really need to have quite an inspiring conversation about Western Australia and particularly about who we are and what we do. We need to be having this conversation in lots of places with lots of different people in light of this multifaceted transition that we need to make very urgently to remain prosperous, but also to take care of our children and our unique and beautiful part of the world and secure a safe future for all of us.

So thinking about Western Australia's identity purely in economic terms we describe ourselves as a mining state and that's totally fair enough because in 22 the resources industry raked in about $246 billion worth of revenue, just over three quarters of it from minerals and 76% of that from iron ore. And the fossil fuel industry brought in a record $51 billion which made up the other 22% of the resources sector. And I think one of the things that we need to start doing is separating instead of lumping everything together as the resources sector. We need to talk about the mining industry and the fossil fuel industry because unless we can make that distinction, we keep offending people by saying we need to get rid of the resources industry, which is not the case at all, it just needs to pivot.

So in light of the mining industry needing to decarbonize and to make some serious adaptations and the fossil fuel industry needing to phase out imminently, we need to ask ourselves about the fresh stories that we can tell and about what the real and reliable opportunities are and what kind of clarity we need to proceed and the way we run things. The close attention we need to pay to what government's doing, to what communities are doing, to what individuals are doing, to what industry’s doing.

And so that's why I'm really pleased to have the opportunity to convene this conversation, I hope we will be having it in lots of places over the coming years as we all get very inspired about what Western Australia can still be. So I'd like to introduce the panel tonight and I'll go straight back to Heidi, who, as I mentioned, is a Nyoongar Yamatji woman.

She's Indigenous Liaison Manager at Curtin School of Molecular and Life Sciences and a member of the Nyoongar Land Enterprise. She studied and worked for a long time in community development and is a passionate is very passionate about Nyoongar led land restoration and economic opportunities through land based activities that are so vital to healing and wellbeing and cultural survival. Please welcome Heidi Mippy.

Dr. Fabiana Tessele is director of Tessele Consultants and a steering committee member of Circular Economy WA. Originally from Brazil, Fabiana’s career has been focused on recovering value from wastewater for over 25 years. She also worked on the sustainable City Project in Dubai before coming to Western Australia. And here she applies her big thinking to sectors including mining and agriculture and property, where she sees huge potential in the application for circular economy in Western Australia. Please welcome Fabiana.

Adam Carrel is a partner in Ernst and Youngs Climate Change and Sustainability Services team. As part of an initiative called The Antithesis Project, Adam was lead author on last year's report, which was called Enough: A Review of Corporate Sustainability in a World Running Out of Time, which was really a remarkable piece of straight talking to industry on the catastrophe that an incremental approach to sustainability will incur in this critical moment for the world.Please welcome Adam Carrel.

And Dr. Toby Price is Manager of Future System Design at AEMO, the Australian Energy Market Operator, whose role it is to make sure we have enough energy when we need it. Which is a substantial challenge as we undertake this transition to managing 100% instantaneous renewables. Toby has a PhD in hydrogen storage and has developed novel solid state hydrogen storage materials. He worked on renewable energy projects across Australia and internationally before joining AMEO. Please welcome Dr. Toby Price.

Now I want to start this conversation a little differently to understand why this conversation more broadly is important. It means that we have to all anchor ourselves in the place that's important to us. And so I'm going to invite Heidi, because she's used to saying what's important about country and what she values and what's precious. But I'm actually going to invite each panelist to talk about what feels like their country. So, Heidi, first of all, to you.

HM: Thank you. I do feel a little bit weird sitting in spaces like this sometimes, it feels like I'm coming from a completely different angle. When we talk about our country, and I think this is the same for all Aboriginal people, you often hear us talk about our connection and Meri has talked about my connection as a Nyoongar woman to the south west and as a Thiin- Mah-Warriyangka which is my connection to the upper Gasgoyne. That connection to country is about bloodlines that are very ancient, and that connection isn’t a physical connections it’s around our responsibility to country as well as the people and all things living on that country and in and around. So I guess for me, I have been working with where I work now. I'm sitting in spaces and conversations like this. I can often get quite emotional and attached to the conversations around country first of all as a life form in itself, as a giver of life or Mother Earth. And without healthy country, we don't have healthy people. Without survival of this planet, we don't have survival of our culture. And for myself as a First Nations woman, if we don't have plants and animals that make up our totem systems, then we lose our identity. Therefore, we lose our culture. And so we talk about that climate fear thing which I always get that concept wrong, what it’s called but I’d like to maybe talk about what that looks like for us as First Nations People. How real this fear is for losing this sense of identity and connection to country, as I feel I'm living with that a lot lately and I think this will come up in conversations as we all talk and we share conversations around the room. How deep that connection to country is and how deep that fear is, when things are lost or not restored or not restored close to it’s best original healthy form. That it is about degradation of an existence of equal and human rights of my people. So that's what country means to me and that's what place means to me. Hopefully that makes sense to people. Sometimes I’m a little bit out there, but that's what it is, it's kind of hard to explain but it is that deep, it is that real.

MF: Thanks, Heidi. That was beautiful. Fabiana, would you like to tell us about what country feels like home to you?

FT:Yeah, that that's quite interesting, because my ancestors, they came from Europe to Brazil in the early 1900s. And so my my background is Italian, and you were right about that. And so home was never a place for me. It was always more an attitude of where I am or how I position myself in the world. And of course, after growing up in Brazil, I lived in many different countries also. I lived in the U.S. and the Middle East, and now I'm here. So I try to bring with me what is important to me, which is water. That's my home and the, whatever I am, that's where I connect and and what I feel like I'm doing something for my home, which is dealing with a sensible way to to manage water rights. And I'm not talking here about water scarcity or that things are drying out. It's about how we better benefit from the different types of water across the water cycle, right. So it's a bit different from, it’s not connected to a geographical location. It is inside me and in water.

MF:You're not a mermaid, are you? (laughing) Thank you, Adam.

AC: Yeah. So I am, I am a proud Western Australian, but I wish Heidi I could speak to such a deep sense of personal belonging here, but I would be lying. I have a love hate relationship with Perth and I love it, but there's aspects of it that I struggle with and I've lived, I don't know, Perth is like nowhere else and I've lived in New York, for example, where it's a city where the city lives through you. Like you step out into the street of New York City and you are just an extra in its grand story. Same with London and all the great cities in the world, right? It has such a life force that it, you know, you bubble along like a bobbing cork in the river of its own story. Perth is not like that. And I think Perth to me is like the great existential city where life and reality and your own mortality is rent in such stark kind of colours to other parts in the world that you really, you really ponder the big issues I think in this place. You can't, life is not kind of hidden behind the kind of the drama or distraction of culture or kind of geopolitics, at least at least in terms of my experience of the place. And for this conversation I just think it's I think Perth is a place that forces you to recognize your individuality a bit more, and it's a place that forces you to stare into the kind of potentials and limitations of humanity more than anywhere else I've lived. And I, and which is why I grapple with it.

But I think, I think in terms of Western Australia being the master of its own destiny, which is the kind of conversation we’re having tonight. That at the one end of the spectrum it's you think that, you know, if you look at what's happening in Israel and Palestine right now in the Gaza Strip, you know, contrast it to that. Here we are, we have so much space and peace and high standards of living and natural resources. We are not some punching bag of history. You would think that more than anywhere else on Earth that we could be the architects of the most fabulous history and be the master of our own destiny.

Like in Florence, 16th century Florence, a city of 60,000 people, half of whom had the plague, could create the, you know, the Renaissance and humanism. What could we do with 2 million of us? But at the same time, with Perth, we always feel as though we'd be doing it on our own. Like the currents of history do not run through Perth the same way as they do with Florence. Like we're going to have to drag them here, right? And that's my, if you thought yours was complicated, that’s my very complicated relationship with this beautiful city.

MF: So can I just ask you a simple question then?

AC: No

MF: Sorry, just one? When you put your feet on the ground, where feels like home for you? Like where do you get that sense of becoming one with nature?

AC: I don't think I've found that place yet. Yeah, I'm too wrapped up in my own nonsense.

MF: Right, Okay?

AC: I'm not, I've not, I've never really ever really pulled my shoes off and sunk my toes into the terroir of anywhere and gone (deep breath) I’m home.

MF: Okay. Right.

AC: Still looking for it.

MF: We've got work to do, thanks Adam. And Tobi then, and what is your response, having heard the others?

TP: I mean those were beautiful responses in such different ways. That was really fascinating, I think mine is probably less complex. I'm also conflicted by my feelings about home and place. I’m an immigrant to Australia. I have deep connections to the UK where I’m from and my upbringing in rural Norfolk. And then I can also empathize with that sense of WA which just feels like somewhat of a dream world. That’s barreling forth, seemingly, under, well we can talk about various powers, sensibilities. And I think for me it's been a process of finding this place and my place in it. And I think that small fish bowl that we have, and the opportunity to actually do things here. To feel like you can make differences is one of the things I feel most connected to being in WA.

In terms of place, I again, coming from the UK, small little fields, little lanes, driving north and just breaking through the wheat belt and getting to the bush and just feeling those enormous vistas and the stars above them. That feels incredible to me. Yeah, but in saying the same things, that experience, it is beautiful, I’m very privileged.

MF: Amazing. Thank you all so much for sharing that.

I want to talk first about what the problem is with considering ourselves a mining town without considering diversity and what else we could be and what we need to be in this climate story. And Adam I want to go to you first on this because you're talking to industry. What are you seeing emerge already that looks like it's going to become problematic for Western Australia?

AC: I want this to be an optimistic story and I think we do have an optimistic story, but there are there are some problematic aspects here. I think starting with government, we don't have a clear industry policy. You know, there's always been this phrase in Australia that's kind of this this, this kind of rote learnt political idea that we shouldn't pick winners in economies and we're not picking winners in this economy, and that's a bad idea. You know, we shouldn't put all our eggs in one basket, for example, and say, hydrogen being one example. We shouldn't necessarily put all eggs in that basket, but from the very top, we don't have a very clear industry policy to make ourselves a winner and to pick winners in Western Australia, I would argue. You know, there are directional policies that are symbolically in the right direction, but there's no real attempt to kind of pick winners within the whole miasma of the of the clean tech revolution. I think when you cascade that down into the corporate space, you see a lot of corporations with lots of pilot projects and government policies have been great at experimenting with pilot projects and there are lots of those going on, but none of those have yet catalyzed to anything that could shake it, even with the eastern states, let alone with, say, Germany and other markets that are really diving into differentiating in these sorts of areas. And so that's, you know the world is changing. We will continue to be lucky though. I'm trying to keep my remarks brief by the way. I know that's always hard for me but I will do it. We have been so lucky as a state to roll from one commodity to another commodity that has opportunistically lined up in time. And that's going to happen again with copper and it's going to happen again with nickel and is going to happen again with lithium, like we do have great opportunity ahead of us in the next ten years. But what stands out in my mind is the fact that Apple, for example, the world's biggest company at various times of the year, has announced that they want to be virgin mineral free in all of their products by 2030. Like the call of circularity now is so enormous that we will eventually run out of luck and we eventually have to take the step of introducing value added technology into Western Australia. And that is where we are so self deprecating. That is where we we can't make the cognitive leap towards not just digging it and shipping it, but actually investing in onshore. We don't have the, we're intellectually self deprecating around it, I think, and we just can't make the cognitive leap to that, but that is where we have to ultimately go to sustain our growth in the clean tech revolution.

MF: Thank you. Fabiana, you're nodding so vehemently. I have to go to you next.

FT: Yeah, you probably remember I am really in the same page. I think it's really about time for us to start adding value to the dirt we are digging from the ground. Then stop thinking that we just do the minimum we can get away with and then go to the beach, which I love. But I think putting an extra effort to really create that, we need two or three generations now to create that culture where we add as much value as possible. And that's going to create new opportunities also for not only for economy and environment, but society as well. People are going to have new skills and different ways to relate to the product that's coming out of here. And that means, okay, we're going to need more energy, we're going to need more inputs, but we also need the smaller scale. You don't need to do huge excavation digging dirt from the ground. You can do a little bit smaller, right? And you can work together with Apple and the likes to develop a framework where you don't eliminate the virgin mineral, but you use it in a sensible way where it's necessary, right. So it’s the same as the energy matrix is it not? Everybody going crazy for electric cars and hydrogen. Let's look at everything else we have here. We have waste that is going to landfill still. We have the sun, we have a lot of things that we are just past blinding it and we get a fever and run that direction. And now let's look sideways and that way as well, right? That's how I feel.

MF: So can I ask you about is it a lack of imagination on our behalf, then, that we can actually sit down and really explore what else this needs to look like?

FT: I think there is a lot of good people here with good ideas. There is a very strong, risk averse culture. So I hear a lot from my clients, oh yeah, this works in Europe, but we are in Australia, that's different. And I say mate, no. No, cows are cows here, cows are cows in Australia and in Europe. The same, so the way to face risk is by eliminating the risk, not about managing the risk. And I think that's the main thing that's hindering us. And our beloved regulator is really sitting in the last century, so we really need to move forward in that space.

MF: And Heidi, I mean, the consequences of this whole energy transition are being seen on country as well because there's such a massive land grab in the southwest. And it seems to be, you know, it's like the Wild West frontier in the sense that it doesn't seem to be managed. Can you tell us what's going on and who's sniffing around for land, and you know, what the risks are?

HM: Inaudible first sentence. Well there’s definitely crazy land grabs going on. I think its concerning that the conversation is all about how the resources industries has grown and how this mentality that continues to be, this extractive mentality continues actually. Which I think is of concern. The second thing is that we look to offset that by buying or purchasing this land, on country and doing really shitty power projects or things that are not consistent, certainly not consistent with our cultural and restoration drivers. So, number one, they’re not going to achieve the outcomes as quick as they should and it's really just greenwashing and then we create extra pressures in the Wheatbelt on our country around housing. Pressures on Wheatbelt towns that are taking employment away from other industries that are already out there. And I think we're starting to create, what we will do is start to create the mining ghost towns that have been created in the past by pushing these industries out of the places that they really don't have a place for. Like we talked already and shared stories about place and connection and all those places where these projects are rolling out there is place and connection for the people. And the risk is now that we start to break that story and connection for people in those regions when we could be doing better things.

MF: So you've got carbon projects, you've got agriculture, you've got exploration for critical minerals, potentially, and what else?

HM: Yeah, all of those. And more recently, particularly this week I was having conversations about the very large number of explorations for rare minerals on my country I wasn't aware of and of all the things, the resources, the carbon. Very poorly managed carbon projects on country. So, I'm more concerned now that the exploration licenses in projects now will potentially roll out and so on in our country.

You know, I take people's comments about how much room we have in this State, but the land it will run out, it is already running out. What is empty to other people is home to many others. What looks barren is biodiverse. It’s you know deserts, it still has healthy ecosystems and we’re really causing a lot of damage when we’re pushing these kinds of operations out into other areas and I feel like we need to be managing this process far better than we are.

MF: Yeah. Thank you. Toby. You've worked on other renewable projects, not just here, but overseas as well. Have you seen this kind of mess come to get tidied up at some point or, you know, what's your assessment of how things are going with this in terms of all of the activities that need to go on for the energy transition to happen and how we're managing it?

TP: That's a really good question. I think that the timing is critical. So, it tends to be the money is available and the right regulatory environments available to make the projects happen, wherever that may be viable. And the challenge is that one almost certainly hasn't thought through everything and manage that in a sustainable way. And you just see a ‘boom and bust’ cycle of successively large roll outs, seemingly (cough makes words inaudible) between. So we can understand what needs to be fixed so the next time those incentives are there, so it's done effectively that that's that the learning from other places. But Western Australia particularly is somewhat at the vanguard of its reach. We are experiencing much higher levels of renewables penetration to other similar grids around the world. So to some extent some of these challenges we're experiencing first and I think I think that's something a little terrifying.

MF: Yeah. So tell us a little bit more about that because we've had an unprecedented uptake of of solar by individual households, right? And that means that the grid has actually not been prepared for the onslaught.

TP: It's amazing. The ratio of on roof solar PV installed by consumers, consumers, you know, voting with their dollars to go out and put solar panels on the roof compared with what we think of the solar farms, these giant paddocks full of modules is not the case with them. We've got circa um 200, we've got 120 megawatts ish of utility scale solar and we've got 2000 megawatts of rooftop PV, which is almost the complete opposite of what's happened in places like California and to some extent over East. So, it's quite a dramatically different scenario that we find ourselves in and an ultimately that, that appetite and that fantastic appetite for consumers to decarbonize their own energy supply does cause challenges that we have to grapple with for an isolated grid that’s connected to any other state or territory.

MF: So we've we've been very excited about putting decarbonizing our homes. But how's industry going? What's what are you able to say about that industrial decarbonization? Because that's obviously going to impact our capacity to relate to the rest of the world, surely as well, isn't it? If we're not, if we haven't decarbonized our own industries?

TP: Absolutely. And the risk is that consumers go on the journey for themselves and you’re left with a grid that is only supported by the industry that can't put solar panels of sufficient volume on it’s roof because they don't have a roof. So I think the challenge will be that we want these investments to benefit all consumers, I’m talking about the consumers on the Southwest interconnected system stretching, stretching up to Kalbarri and down to Ravensthorpe. That's the size of the UK and services just 2 million people. That's the opportunity I think, and it's interesting Ministers in Parliament on Tuesday reaffirmed that and I’m sure we’ll get into this, but that the transitioning services that decarbonise our broader energy systems must be driven by those industries and not consumers. Who of course are voting for dollars.

MF: Yeah. And I've seen a lot of big question marks around that from comments from people that I'm connected with in the industry. So I'd love to just give you for a second the carriage of the entire energy transition here. If you if you were to sort of, you know, step through like what's the low hanging fruit, what could we get done quickly and easily if only we had, you know, the right policy in place, and the right leadership.

TP: I don't want to get geeky about it, but we just we just completely overhauled our market structures, operated by AEMO who I work for, operates market in Western Australia, and we completely, radically shifted the frameworks on which we procure energy to try and make it much more robust to the energy transition. And so with that framework in place, there is the opportunity to essentially utilize all the negative because every, you know, we all talk about network transmission being critical, and it is critical, but there is network resistance and there are points on that network where we can connect with amazing resources, new wind and solar projects, and places where we can connect storage that will allow without significant technical challenge and offsetting running cold running hacks that that seems like pretty quick wins.

MF: Yeah. Are you in a position to be able to say that you know, in in your workplace or is it very much the day to day? Because when we were talking earlier, I as in a few days ago, I had the sense that you were deeply frustrated.

TP: I think that's a function of it not being an easy challenge right! This is not, an energy transition is not easy. And dealing with that transition through a variety of regulatory instruments, markets and, you know, private money is not is not something that's particularly straightforward. I don't snap my fingers and say, thou shalt build a large solar farm precisely this location. That doesn't happen, that's not the way we’re structured and I think that's probably a good thing. And so there are frustrations but there are absolutely opportunities.

MF: Thank you. Fabiana, I want to go to you, because when we were talking previously, you were saying that you see Western Australia as having a huge amount of potential in terms of using the concepts of the circular economy. Can you talk to us more about that?

FT: Yeah, I could give an example in the in the water industry, of course, where we are now moving to a new desalination plant for supplying water for Perth and Water Corp, saying it's going to be fully renewable, all good and they buy energy from Toby, it’s not renewable energy. In my view, in a circular in the circular mind, the water utility could be producing all their own energy from their wastes, it’s just a little bit more effort on the way they treat wastewater and how they integrate that with energy suppliers. At the same time to use the excess heat from turbines, for example, and make the entire wastewater treatment plant more efficient. So this is one example where instead of looking, okay, how can I sort that inside my house? it's much easier to go to the market and buy renewable from the grid. So now we need to include both, right?

We need to do at home your homework. And that's a big part of the work I'm doing. The red meat industry, for example, we are being we are finalizing now a few studies where we can fully power our red meat processing plants from their own wastes. So instead of going to Toby and saying, Hey, you have some renewable and let's put another wind farm here, let's put more solar panels there. So there is a little bit of thinking out of the box. It's a it's a great opportunity, I think. And then also connecting energy and water. They are not separate. They are together. So there is lots of synergies you could be leveraging from there. And the classic case is in the Middle East, in Dubai, they always produce water and energy at the same time because the water becomes the battery for when they have the off peak electricity production, you know, so you produce water, you store water, and then you use that as your battery right. And that's very clever. At the same time, they produce desalinated water using the excess heat from the gas turbines that produce electricity. So it is all connected. Here you propose something like that and they look now not the energy is not our business. Thank you. Go ahead. So I'll add the lack of cross-sector conversations I think is the main thing that I keep struggling in.

MF: But I was saying in the intro, sorry I will come to you in a sec, in the introduction that you actually work across a number of different sectors. Do you see more interest in one sector particularly, to uptake this idea?

FT: The private sector, definitely, yeah. So the food industry is a great synergy. I'm working now with the grain industry and the red meet the industry and some of the forest industry on integrating all the processes together so they all benefit and that includes recycled water for irrigation, that's include producing fertilizer for the forestry industry and the energy for powering the plant. So I think if everything we are doing goes forward, we might have the greenest red meat in the world going forward. It's going to be really cool. I see that opportunity really there. Yeah.

MF: Thank you. Heidi, in the introduction, I was talking about how indigenous knowledge is going to be really critical for us to restore boodja and this is obviously part of, I guess, a slowing down potentially as well of how we actually run our lives so that we can, you know, really pay more attention to our environment and our custodianship of that. Are you able to talk to us about, you know, the key kind of principles or ways of thinking around this?

HM: A around the knowledge integration?

MF: Yes, please. Yeah. Because I think often people say, oh we understand that we need to incorporate indigenous knowledge. But, but actually what is that? What are the concepts that we need to start thinking like?

HM: Hmm, okay, I was actually thinking as you were talking about, about this in the relevance to traditional knowledge and conversations with Nyoongar people and First Nations people, because there are a lot of pressures from lots of different people talking about these new industries. And it's very confusing when you're not a scientist and you're not a business person and you are every day Aboriginal person, Aboriginal corporation, to be expected to make informed decisions about about these things. So that's the first thing I want to say is it's really difficult to make decisions like this under under pressure and in short time frames. I love the example that you give because the example that you give around wind and water is more of a holistic view and so when we when we sit on country, we feel everything in on country and it is more holistic. So we're not siloing like forests. I'm working, I'm involved in forestry industry, I’m involved in ag industry, I'm involved in fish, fisheries and people like, I don't like forestry, don't particularly like ag industry and I like fish, I like eating seafood, which is why I love fisheries.

The reason I'm involved in all those things is because we need to look at things holistically, that they're all segregated in or in silence in government. So if I'm not at the table in each of those things then you miss out on conversations. So the example that you give is that if someone came into the conversation like this, then we’re able to better understand and put this in the context of how to bring Aboriginal thinking into the conversation and certainly this would be better received. This concept or this idea in Aboriginal community, they’re one, they’re connected but water on it’s own is very difficult to separate. So therefore I think that that cross collaboration is really important and that it will be really beneficial for our community for people to have those conversations prior to approaching the community, for that input and discussion and collaboration on projects on country. Because we look at, there are wonderful examples and, you know, my boss, who people might know, is a very brainy and influential man, and talks about many of these projects and will support these things but there’s always a compromise or an impact on something else, right? So if we're not talking to each other then we can't be clear on which compromise impacts we are willing to have. And so that and that's what's important. So I think that slowing down, big picture, mapping that out, because we go big picture out and then back in. Thats the process that should occur.

MF: Thank you

FT: If I could just add one little word that in the concept we are creating for the Southwest facilities, it is included to have a visitor center so people can go there and experience that concept and also a training facility and we are talking to Tafe to have a special course there for training on understanding, clarity, understanding, but not only from a strategic point of view, but from an on the ground operation point of view. You see the waste coming in here and you see the power being produced there. And I think that's very intuitive for the community to get engaged and understand what we are trying to achieve. So yeah, in the first time I said that to my client, I said, I want your new facility to be a tourist attraction in the Southwest and they said, oh you crazy and I said, yes I am. And now when I say that they like it. I made a nice rendering, it's looking good. It looks like Optus Stadium. And it's fully accessible and you know, on your sheet. I'll go there and say, look, I'm proud of it now and we are dealing there and I think that links to the community engagement to be open, you know, come here and see what we are doing and that's the what we are trying to achieve. Yeah, and it's great.

MF: Thank you. Toby, I meant to come back to you. You wanted to add something to Fabiana before?

TP: No, I was, I was reflecting on the interoperability between water and power, and it is something that we do think about. We do talk to water corp quite regularly and they are very balance consumer in some ways. But I mean, the opportunity to start simply a kind of a generator and a load is really interesting.

FT: They could be producing inside their pipes, in pipe hydro, right. Every every water pipe. But yeah.

MF: I want to ask about the implications for us for, you know, not doing the right thing around decarbonization. And Adam, perhaps I can go to you on this because the implications for business are quite significant. Starting from, is the the carbon border adjustment mechanism January 24, is that when that starts? So there's a bunch of stuff that's going to impact us whether we're doing the right thing or not. We won't have as much say any more. Can you tell us a little bit more about what that's going to look like?

AC: Yeah, sure. And in answering that, let me respond to something Heidi mentioned in her response to my remarks, which I completely agree with, which is that just because you are mining a commodity that is going towards some ultimate clean tech destination doesn't make it a good thing. And so much of the clean tech industry is going to function in exactly the same way as any other boom industries, so they will rush out in advance of regulation and with a frontier mentality, and local people suffer, local environments suffer, and just because they're digging up lithium versus gold makes no difference. So I completely agree. And to arc it back to your question, the, even beyond carbon, I think and maybe this is the kind of way I should've answered your first question, which is around what, what is the underlying problem that we need to solve. This process is that every single indicator of biosphere risk health is in decline in the world, every single one. And we talk a lot about carbon, but there is not an indicator of biospheric health that isn't in some form of decline and some of those are precipitous decline. And we are getting to, the, we're slowly arriving to this point. And one of the critiques we wrote in that report is that we've been talking about sustainability for years, but it's been completely decoupled from the science of planetary boundaries. We're just bringing in this concept now, which is slowly taking root around, being incrementally better doesn't matter all that matters is whether or not businesses can prosper in a way that does not undermine biospheric health. And things. the European Union is a leader for that, but that is going to be the key kind of cleavage point in our industry.

And that is where the Australian and West Australian mining sector has to go. Is is around regenerative practices. We are we are inching to a moment where things like the sea ban, which for those unaware is a carbon border adjustment mechanism in the European Union where the EU are going to penalize imports that are emissions intensive to be able to improve the economics of of low carbon products. And that is indicative of a trend around the world. We're beginning to see a separation of economies and we need to track towards the economy that is paying a differential dividend for products that are manufactured in a way that doesn't undermine biospheric health. That's key to the point. We don't just want to ride the next wave of this boom that clips the ticket on the clean tech revolution. We want to be the industry that actually demonstrates the reality of regenerative mining. That it is possible. We need to be at the vanguard of models of mining that are decoupled from biospheric decline. We need to be at the vanguard of motivating consumers to pay a special dividend for that. We have to be at the vanguard of the science of planetary boundaries. I think that is the crux of the matter.

We have to abandon incrementalism and the sense that ‘just as long as we improve upon our metrics of the prior year’ and be the economy that can net off its growth from global environmental decline.

You alluded to commentary on degrowth, and I don't want to come up here and be the more commercial guy in the panel that just thinks growth is a prima facie good thing. I'm not that person. I think we do actually have to steer into the challenge, not just of addressing the climate crisis, but addressing it by the biosphere crisis, by creating an economy that is ultimately decoupled from environmental decline.

MF: It seems to me, although particularly I don't really look beyond Western Australia to be honest, but it seems to me that hardly anyone is working towards anything that is a science based target. It seems to just be like “we're heading in the right direction. We think we'll get there eventually. 2050 is a long way away, is not going to be my problem”. Am I right about that? I think you said that there is no sustainable organization in the world.

AC: Yeah. Which is terrifying but true, that there is not a single sustainable corporation on the planet. You might even talk about Patagonia as being iconic. Even they are not. Patagonia does not even know how sustainable it needs to be, by when to be sustainable. That is the shame of my industry, which is that we've created this illusion of progress. We've created this narrative around corporate sustainability, that is completely untethered from any actual baseline scientific reality. That is not meaning that we are in gross ecological overshoot. That is the massive mindset revolution that has to occur in economies around the world, to know what it means to be sustainable. People say, “ it's so complex and subjective and abstract”. It's not. It was written in the Rio Earth Summit. Sustainable development is the capacity of a current generation to better enjoy economic growth to the extent that it does not undermine future generations capacity to have equal to or greater than levels of economic growth, which means preserving the biosphere.

It's really simple and we have to just stick to that actual core definition of what we're here for.

MF: The Rio summit was 30 years ago.

AC: Yeah!

MF: So, Toby, can I go to you on science based targets? Do you have those discussions in AMI?

TP: We have targets , but they are much more specific to the energy industry, the markets, the operations. On a societal level, it's critical that technical standards in your industries start to say, well, this is where need a new metric that makes sense.

To get the energy sectors [indecipherable]. That's going to capture the sustainability of how this is running. We have targets [indecipherable]. We were aiming to understand all of the technical challenges that by 2025 we were already in a position where everyone's rooftop solar, all of the wind (power) that we have up north. If it had all been running as it was, If it was allowed to operate correctly, I believe we could have turned every column. [indecipherable]

MF: Yes. Thank you.

Fabiana, do you have clients who ask you specifically to guide them towards science targets? Like to work towards a 1.5 degree pathway?

FT: Yes. Basically the sustainable city in the bio was one of them. They wanted to work on that. The other interesting thing they wanted to include was the social aspect in sustainability, very much so. It was not only about the environment and economy, but how about the people that are going to live here? how you can think about them.

It was super interesting to develop an entire community with almost two and a half thousand people, where they are connected. They walk home, they don't drive to the garage, isolated. We created a community that not only reaches the target of reducing the 1.5, we wanted to make it to two. Make it to two degrees!

We calculated how much offset we had to have in our development to impact proportionally, to the world population, the reduction of carbon emissions too. That community now is carbon positive. It produces 120% of their needs.

MF: When was that completed?

FT: It's amazing. It was conceived in 2011. The land was bought in 2012, and the first house was sold in 2015.

MF: You told me 500 families? So around 2000 people are living and working successfully in the desert.

FT: In the desert, yeah. They have urban farming there. They are fully sustainable, energy wise. They created a commercial model where the commercial areas of the community that are restaurants, supermarkets, nail salons, whatever, are rented for the benefit of the community. They don't need to pay levies, they don't have strata fees and that's the part of the social benefit from living there, right?

So is the urban farm. This idea came from a joke, they asked “what's the most sustainable transport method here?” and I said, “Horses” right? They eat grass and they’re simple like that. So now they do have horses there! They also have Teslas, and if you buy a house there, you get a discount for buying an electric car. They went all the way to speak to Elon Musk in the US for that. It’s a really holistic approach. I'm very passionate about that model, you know.

MF: Heidi, I know you'll be interested in this because when we were talking this morning, you were talking about the potential to create sustainable communities on Songlines, in fact.

HM: You shared this example with me, and I think this is a beautiful example. The Wheatbelt has become very quiet, you know? During COVID, a lot of people moved out of Perth and populated those areas, but most people have come back to Perth again now. I'm seeing a real movement in the region, in the Wheatbelt, for people to move back out and look to restore country. People's values have changed and I feel like people have understood the sense of urgency to do better from a cultural perspective.

I'd love to connect those songlines across countries. From our oceans and back out into the Wheatbelt, up north and back into the desert, in fact. If we can do this and start to strengthen our communities, not have people living in isolation and have people living sustainably, on country with good food security. With traditional foods and other foods, I think that's a far better option for enrichment of life and learning.

Sharing the beautiful history that we have in terms of first nation culture and also the histories and cultures of people who are here now, I would love to see this. I think this is far better than creating these ghost towns around the potential models that might exist or go out there. So sure, you know, you only know what you know.

So sharing examples like this with community I think would be really well received, particularly in our communities. And I think that would be wonderful. It's one that lots of people could contribute to and certainly could occur in a co-design approach.

MF: Yeah, it's a lot about the climate justice of the conversation as well, isn't it? Making sure that people are safe and secure and in places that matter to them?

Yeah. You two should talk. I want to ask whether there are ideas about what we need to be taking to the world. If it's not fossil fuels and it's not minerals in their raw form, what else could we be doing that allows us engage in trade globally? I don't know who wants to answer that question first. Adam do you have something that you'd like to add?

AC: Look I think I think one of the issues actually is that we tend to view our future through the prism of some mode of industrial output. And I think that encumbers what Western Australia could be. And I think if I was to pin the tail on the one thing that is obstructing Western Australia having its own little renaissance, it's corporatism. It's viewing the world through the paradigm of what a business produces. Because whenever we have conversations around climate change and the failure to address climate change, the nub of it is always political will and it came up in you know your question towards Toby, it's this this frustration that we don't have enough political will to solve this problem. But what's weird about that is that we always say there's no political will and when we talk about climate change and sustainability, but when Australia go to the ballot box and when most large democracies go to the ballot box, they do not vote for interventionist governments. The dominant Center-Left block, which is actually dominant in the US and in many other countries around the world, and this kind of socially progressive, economically conservative block are very resistant towards interventionist government. So it's a weird dissonance where we in the moment we blame an absence of political will, but we never actually vote for interventionist government. And what the world has been voting for the last 30 years since the Rio Earth summit has been, ‘Yeah, we want progress on the environment, but we want to do it ourselves.’

And that's the argument we're taking at the ballot box. We're saying we don't actually want government do it. We want government to set a policy ambition and we want the individuals and the private sector to actually fulfill that with real world outcomes. And that is where everything is falling down. It's the one thing that has to be activated for the world environmental crises to be solved and for Western Australia's opportunities maximized is for the great privilege white collar mass to actually accept the responsibility is theirs.

And Perth is such a corporatized economy, I think more than anywhere I've ever worked. Everyone that goes to work in the city here is in a corporation and they view the world and their responsibilities to the world and their intellectual potential through their position description and the things they are paid to be responsible for. And that is the great kind of cancer on our opportunity that we have to break the shackles of seeing ourselves as employees and liberate because most of the world's brilliant process engineers are employed, for example, in the oil and gas industry. The intellect is there, all the capital is there, but it's locked up by people that go to their cubicle and see the world through the prism of their job, as opposed to unleashing their intellect towards the resolution of these problems. So that's my sense.

FT: I'm a dropout from corporate and I'm a process engineer. And I'm saying, sorry to interrupt you, but please, I just found that interesting. There is lots of dropouts from corporate starting little operations like I am, and I am attracting people that come to me. I want to work for you because of the different way to see life. I'm not locked anymore to the big billion dollar American corporate. Well, the way I work is very, very different. And I'm seeing there are lots of lots of people doing the same. They cannot put up anymore with the 9 to 5 bus utilization and all this kind of, you know, we don't do that anymore. And I think that there is a niche of people popping here and there. You'd be surprised. Some of this room.

AC: And to conclude on that point because I agree, I think if we could export anything to the world, it wouldn't be a widget. It would be the decorporatization of the world and the liberation of all these smart people to actually drop out and drop in to these great meta problems of our time. That would be the most amazing thing that we could demonstrate here.

MF: Toby, what do you think of that? (some inaudible comments from Speakers) He’s getting his thongs out of his back pocket.

TP: Yeah, absolutely. Well, I think it brings lots of premises in all sorts of different sectors. It's part of the role of the corporation and community in its objectives and that’s how you try to figure out goals.

So I came from a renewables developer background to the building project, most of them off grid satellite power system type things, and that was wonderful. So we're setting up more solar, setting up diesel generators in the bush, that made me feel good. And after that it was where do I go next to do best for this energy transition as well. Whilst AEMO is not the perfect place to be, because I can’t question their role or where they’re at, it is central to one of the big challenges we'd like to bring about, across the industry linkages, these sort of hotspots.

I mean, we have a role in electricity, gas and certainly the hydrogen economy is wrapped up in that but it doesn't seem to work fine in all States. So consider the harmonization of those things, which is actually rules in place.

MF: So are we saying then that we could consider Western Australia as an entity in its own right and not worry about global engagement?

FT: No, by any means.

AC: No, it wouldn’t be okay?

MF: Just checking?

AC: Yeah. No, it's not a successionist idea. It's just the West Australians love that there is everyone is a kind of closet secessionist here. But it's the fact that the thing that needs to change, it's not a technology fix or a capital fix, we've got the technology and we've got the money, we are just, there are more people alive today that are excessively overeducated and have remarkable standards of living that, you know, that whole Kantian view that we would get to a point in history where we would just couldn't help but grapple with the great problems of the world because we've sold everything else. We're fricking there now. But corporatism is this great thing that drags all of these educated, lucky people that really have no other role in life than to distribute their luck throughout the world because they have everything they need. And it takes that great bounty of potential, not to say that in any sense they’re better people, they just luckier people that have more moral responsibility. And it stuffs it into the atomization of the corporate world where people they just do that one thing they've been told to do. And they really don't think they’ve got the latitude to go beyond the pace that their organization wants to set and that is the great trap, that is what sucked in all of this great intellectual potential and is trapping. So that the thing I would want to export and I would love to be a kind of a birthing ground for the for a revolution of sorts where we are we get we get tired and bored of just being a dull suburbanite, corporatized city and spark a revolution that would go around the world to force the moral responsibility on people to actually take their good fortune and spend it.

MF: Thank you. Heidi I want to go back to you because we were talking about the potential inequities that are created on Noongar country again as big corporates have the money to invest in in taking up land that then takes away opportunity. Can you speak a little bit more about that and what the worry is around that that inequity that's likely to be created. Speaking of money and who's got it?

HM: Look, I think it's, one of these big corporates came to us recently in conversation to talk about their intent to restore country and to really engage with the Noongar people. How to best do this because we know you have the knowledge, how to best heal the Wheatbelt. Which we do and it can be done, for anyone who seems to think that it can't. And I said to them well just give us the land and we’ll do it. We don’t need to be told how to do it, just give it to us and trust it will be done.

But they weren't prepared to do that and just moved on to the next conversation. Now you know that might sound really silly and would you really expect them to give you this land. What we want really is this little finite piece that costs maybe one million to them, its nothing. If we offered to put the resources there ourselves, our knowledge and our people and restore country in our way. This is about intent, are these corporates really willing to do what they say they are going to do? And I believe for most of them the answer to that is no. People are looking at partnerships, but really I think they’re looking at cheap labour, they’re looking at ticking boxes, they’re looking at ESG or raising their ESG. And I think this is just being abused on country and I think that there is a power imbalance in these conversations. People with money are coming to the table with those of us who don't have the money or power and just expect we’ll take those carbon projects that want to put three or four, sorry lets be real, four to seven species on country saying, you know, we’ll work with you, we will work with you’re people to plan this. And we say, no, what are four or seven species on our country going to do to heal it? It’s going to do nothing so we would rather not be involved in that project. If they are going to employ our people for six weeks to plant a couple of trees that are probably going to die anyway in the first twelve months. So yeah, there's a power imbalance both in the funding and the access for us. Particularly around our country, as we've heard we’ve got signatory title but we don’t have access to the plan. But absolutely open to partnerships, to sharing our knowledge, to sharing our resources but its not an even playing field there for us.

MF: Thank you. I want to give people in the audience the opportunity to ask questions, so I'll just finally give each of you the chance to just say whether, you know, what would help right now to really unlock something in your world, whether it's a policy or a particular type of leadership or narrative, whatever else. What would help? Toby, can I ask you first?

TP: Oh ,so many things? Yeah, it's I mean it's a good question. It's precisely what we need to be asking as a society. I think the critical piece now is doing the work behind the plans that exist. We have a lot of plans that cover near-term needs from a power system perspective. And we're sitting on them and we're not moving fast enough to make these things happen. We've done the very challenging but very time bound decision to retire our state-owned coal in WA which is fantastic, but we need to replace that capacity of the power system, otherwise the lights won't stay on. And there is a need for sustained investment and the frameworks need to be delivered. Please come and make it happen. Ultimately, that's where we're at now, we need to make some of this stuff happen.

MF: Thank you, Adam.

AC: The easy answer would be we need industry policy to be able to cultivate genuine hubs of public private partnerships for, you know, new value added technologies and clean tech. But riffing on that last point. I would love to see a kind of citizen led rebellion to force the corporate incumbency to follow through what they're saying they're going to do. There are a few companies out there that are genuinely pushing the envelope to try and achieve science based decarbonization and sustainability, and the rest of corporate Australia is sitting back waiting for them to fail to suggest that it couldn't be done. We need to support those companies that are putting themselves out on a limb. And we need everybody in the broader corporate world to hold where they work to account and where they bank to account and everybody else to account, to say that you have to actually follow through on what you're doing. We're in a critical ten year period, where if it's greenwash, the whole world will suffer. Hold them to account and don't let people out of this current problem. Corporate Australia and boardroom Australia has been disproportionately captured by the right wing good old boy brigade that are disinterested with this problem and aren't but rising to the challenge. And they need to be overthrown by a much more activated civilian and corporate population that aren't going to stand by and allow it to happen on their watch.

MF: So community uprising for you?

AC: Yeah, one way. Yeah, succinctly put.

MF: Okay. Thank you, Fabiana.

FT: Yeah. I agree that in policy and regulation and government leadership is number one thing, and I can give two little examples that help to drive a more secular world. For example, when I was in the Middle East, it is a legislation that it's forbidden by law to not recycle water. You have to. That's your problem, you do it. So the technologies there, there are plenty of capable people to do it. Here it's almost the opposite. If you want to recycle water, you have a list of burdens to go through to be able to prove that, you know, you end up giving up because it's so hard, right?

In Queensland, I gave a step forward. They have something called end of waste code, so you can only dispose of something in industrial world if you prove you could not use it. So if you could not produce energy from it, if you cannot recycle it. So there is a little bit of a step forward there in Queensland. So yeah, something a little bit more bold in the regulation stage.

And then in parallel to that, drive the industry to aggregate value. So another example I have this from the carrot growers from Myalup. They approached me asking, We need more water Doctor. The water is getting saline and there's not enough. And I said, No, you need to change crops. That's what you have to do. You need to plant less of something that cost more than carrots. And that time it was $0.99 for three kilos of carrots. And I was like, plant mushrooms, do something else that doesn't need that much water. They cannot think from the other side, right. So change the perception of value, I think is very important across sectors. Yeah.

MF: Thanks, Fabiana and Heidi, what would help?

HM: I want to say genuine relationships, without sounding stupid around that. So let me go a bit deeper and talk about head, heart and spirit, if I can. To say that genuine relationships mean that people are connecting, connecting with that knowledge genuinely with each other to grow knowledge is very important. Connecting through heart in real relationships and taking the time to do so. But at the end of the day, we're not connecting through spirit, that is the spirit of each other and the spirit of this country, and I just don't think we’re heading in the right direction. So for me, I think we get that piece right then the rest is going to empower.

MF: Thank you so much. My dear friend Felicity is going to pass the microphone around to anyone who would like to ask a question. Can I get a sense of whether, someone has to break the ice, that's all. And then after that, we'll have lots.

Gerry, thank you.

Gerry: I considered it now, but I think more insight from Adam. So what’s your thoughts on, so we have a food business here in Northbridge, we’re a Noongar business and do a lot of corporate catering for lots of the mining sector, also for governments. And recently we discovered that, we tried to become carbon neutral, so we engaged companies to try and make us as green as possible. We source local, we stopped buying things from overseas. We’re doing a lot of things generally for a small local business. We’ve got an amazing team, local Noongar business but also focused on LGBT and minority groups. When we pitched our business to, I won’t name the company, we pitched our business to an oil and gas company. We found they weren’t really interested in all that stuff, which really like, bottom line this is what we are prepared to pay for your service.

Even though when we rock up with their catering we see that people are rocking up in vans that aren’t air conditioned , pulling out food from station wagons and delivering food. Even though we’ve got air conditioned vehicles. What are your thoughts on (inaudible few words) and all those things that are high on their agenda but it isn’t translating real grassroots. What do you think the mindset of oil and gas really is, what are your thoughts on that?

AC: On the question of why aren’t they putting their money where their mouth is? I think there is a huge amount of greenwash swooshing through the economy. There's a huge, massive disconnect between the stated assertions of companies and what they actually live and believe in. And it's one of the true crises of our time and. that's why I mean, that we don't, our society tolerates that dissonance. We've allowed the vernacular, the discourse of sustainability. Anyone gets to say somethings natural or clean or green or sustainable, etc., and no one really holds people account to actually demonstrate that.

And it sounds like a niche issue, but it's a huge issue. And so I think that would be the first thing I would say. And to feel emboldened to call people on that because there's huge disconnect. Corporate corporations are so balkanized that the person, the procurement company has probably never read their sustainability report, has no idea what their sustainability are and might even help to remind them of that and trap them in the paradox of their of how passive they are around that problem. The other thing I would say, however is that, and I'm sure this doesn't apply to your business and hearing you speak, I'm sure it sells itself, but the whole sustainability advertising space, generally speaking, is pretty poor. It is, you know, we rely upon these really deep dated notions of being green. It's not a sexy or interesting vernacular. And I think there's a whole opportunity now to kind of disengage from the old Dow way in which we talk about sustainability, which is always a bit kind of the broccoli party we're talking about, versus actually I think there could be a whole rebirth in how genuinely sustainable enterprises talk to themselves in a more daring way that doesn't borrow from the old broccoli vernacular, but actually gets to jazz it up and be bolder with its. Again, I'm not suggesting that you're not doing that, but I think the general sustainable product space isn't capturing any any of the opportunity, I think to really burst out of the of the vocabulary it's been given to talk about itself.

MF: Thank you. Does anyone else from the panel want to respond to that? No. Okay. Another question, Larissa. Oh, hi Ruby. Do I know everybody here?

Ruby: So as a student who's preparing to enter the property development space, I'm curious to hear more about how, Adam mainly but also open to the panel, your thoughts on dropping out of the corporate world because I guess right now I have plans of the corporate job. And yeah, I'm curious to hear what you think more specificly that looks like. And I guess in your role how you're acting on that as well.

AC: Great question. And I don't want to hog the microphone on this one, by the way. But just to answer, the first thing I want to say is I'm a 42 year old guy that's been working for a corporation for 15 years. So I'm no I know pedestal here and I did that to be able to enter the property market. You know, so I didn't choose the path to, you know, go to the picket line at the Tarkine. I took a job for the most cynical of reasons to be able to kind of, you know for the things. So I completely understand your dilemma and I don't want to be therefore in this position suggesting that the younger generation go out there and charge quixotically at the problem. I think you should go into the corporate world, but I think it's this sense that you've got to go in there and behave. We’re so conformist, we’re so, there's something about corporations that you go in there buzzing with all the things you've learned in your university degree and restrict that to the tiny aperture of liberty you're given to express yourself in that mindset. And after a while you won't even notice it. You're talking through the kind of surgical language of your code of conduct, whatever it permits you to talk about. And that's problem. So I would say go in there and be bold. Don't feel as though you have to go and work at it you know outside of that universe but just get in there permeate but don't let it censor you.

Self-censorship in the corporate world is a bigger issue than actual overt censorship. And if you can reject that, you'll be surprised you won't. You might have a few jobs before you find the right one. Get into the mix, but just don't let them, you know. Yeah.

MF: Thanks Adam. I want to explore that with the rest of the panel because you went Toby, you went from academia into this role now, but the other roles were more kind of entrepreneurial weren't they. But what's the experience? I mean what would you advise to Ruby on that?

TP: Well, I've been reflecting quite a lot on your comments about it. It is true. But at the same time, I think what one confines the places in the industry, when you apply one's own capability, the objectives of the corporation in the reboot are strong. So sure, you can try and mold corporations and it should work, but you can also seek out the ones that think making a difference in thinking contributes too. So I think it's probably a balance isn’t it. There’s no corporations that doesn't require a shake up, doesn't require previously thought, it doesn't require blurring boundaries of what their existing efforts focus on. But I think equally thinking what to apply your capabilities too is critical.

MF: Fabiano what would you advise?

FT: Yeah, I have a very different advice. I had the same feeling when I was around 24, 25, and I thought, Me, I cannot have a job? I cannot, I don’t know, I don't like bosses, probably. And I started my own business straight away from uni. I was a kid, really. And I asked and advice for lots of older people. Like, what do you think? What should I do? And then I remember a professor at uni said, You have to be very good at something. Choose what is it that really moves your heart and you really like it and you be very good at that thing. In the beginning I was just doing water testing, well drug testing, meaning testing how to use those chemicals in the water to clean water. I was really good at that. And I used to sometimes have a tear here and I see that working like, wow, that's nice. So people are flying me over to do testing for water because they knew sometimes they were having problems in operating wastewater treatment facilities and Fabiana knows how to solve it. And they flew Fabiana there and I did because I had in my heart, you know, and by then I started to expand a little bit more in water. I did my PhD and then I started to go into different areas of water. But it was really just following my heart and doing what I really knew I was good at and not being afraid of it, you know? And in the beginning it was hard. I didn't have money and it took some time, you know, for things to pick up. And then later in life, I was almost 40 already. I'm 50 now. I got a job in a corporate and I thought, that's great because now I can get all this knowledge I have and come to a company that's 100,000 people large and be able to multiply this knowledge. They almost killed me, my soul and everything. And I was like, I love planting, you know, when you just don’t water the plant and you’re like Mehhhhhh. And then I was both again I started again my own here in 2016. Now it's been seven years and I'll tell you I'll never go back and in my offices always open. Sometimes people knock on the door. I want to work with you. And I said, What are you good at? And they say, Ahhhh. I said well, when you have the answer, you come back and then we can have a chat. So try to find your answer.

MF: Thank you, Heidi. What would you advise?

HM: So I think when you're young, you should really look to, who you look up to and who you want to learn from. Because when you’re young and you finish school or you finish your degree and you think you’re really clever because you’ve done all this great study. But you’re still not as clever as you think you are. Really there's still a lot you don’t know and even when you keep studying the more you know the more you don’t know. That’s my attitude to education. So for me I think the greatest value I’ve had is around going into spaces where I can learn from people, you know, be shown by or with people I look up to. So not lock myself into an industry or organization and you know, get the most out of that learning. And then not be scared to change out of that space to be able to go on to the next journey. The next person who I can learn from, who I can grow from. So I think when you feel like you stop growing, or you stop sleeping at night because you’re challenged by things that you're not in the right space. So once upon a time it was do this and then you do that job for the next 20 years. And I think those days have probably long gone for most people. So I'd be going, looking at an organistation, who’s in there, Oh I don’t know about that person, they look really cool, I want to be a bit like them. They all know that because they don't believe I want to be seen like them. That's how I taught myself to play basketball, I actually looked at the best basketball player and copied him. I got on court and then I was playing against them when I was sixteen, because I copied him since I was a little basketballer player. It's exactly the same in business, so that's my must.

MF: Thank you. I'm glad I asked you all. Thank you Ruby great question. Who else has a question? No further questions. You just want to talk to them privately. Okay, go Larissa, its all yours.

Larissa: I wanted to ask, the science of science climate change, whether there’s any indigenous science. What can we do to elevate science in our public and private decision making here in WA? Because I don’t see it being elevated sufficiently. Particularly climate science and biodiversity science that informs people, it could the Montreal Biodiversity Agreement which is driving green in financial systems which is driving green capital which could maybe be tracked in WA.

And then the other issue for the panel, it’s starting to get really hot really fast. So how often are you thinking about that as you go about. So two questions, one about science and one about Australia getting hot.

MF: Who would like to start?

AC: I've always gabbed first someone else has to do it.