In Conversation: Intergenerational dialogues on living with HIV

In Conversation's final instalment for 2023 offered a thought-provoking exchange spanning generations, delving into the diverse life journeys of individuals living with HIV.

In collaboration with the Western Australian Aids Council, listen to a compelling discussion shedding light on the distinctive narratives of those openly embracing their HIV-positive status and what this has meant historically and in today's world.

Panel

Diane Lloyd has been part of the Peer Based Harm Reduction WA team since 2009 as a Community Development Worker. She is currently the staff representative for AIVL (Australian Injecting & Illicit Drug Users League) and sits on the Board of NAPWHA (National Association of People with HIV/AIDS) and Femfatales, a sub group of NAPWHA for Women Living with HIV. Her presentation at the 2019 Australasian HIV&AIDS Conference held in Perth on 17-19 September, led with the title: Women and HIV - Why are women still invisible?

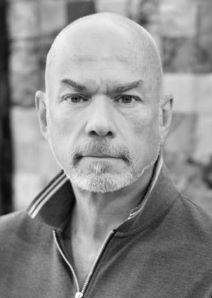

Mark Reid is a founding member of WAAC and has been involved with the HIV response in WA for over 35 years. He was previously employed at WAAC for 25 years in a variety of roles encompassing education, prevention, care and support, as well as fundraising initiatives for WAAC such as STYLEAID. Over his time in the HIV/BBV area he has held several positions on both local and national boards. He was on the board of the AIDS Trust of Australia for 7 years and Deputy Chair for the last 3, NAPWHA Board member for 10 years and Vice President for 3 years, committee member on the Australian National Council on AIDS, Hepatitis and Related Diseases (which was a 4-year appointment by the Federal Health Minister), chairperson for PLWHA (WA) for a year and a board member for 3 years. He currently holds a consumer representative position on the Sexual Health and Blood Borne Virus Advisory Committee and on the WA Primary Health Alliance. Mark is also the founder and current Artistic Director of the PRIDE Queer Film Festival.

Rhys Ross is a HIV Peer Educator for WAAC. He is a compassionate and dedicated HIV Support Worker with experience providing essential care and support to individuals living with HIV. Passionate about empowering and improving the lives of those affected by HIV through comprehensive support services. Skilled in fostering a safe and inclusive environment, promoting education, and advocating for positive living. Committed to making a meaningful impact in the lives of individuals and the broader community.

Facilitator

Professor Anthony J. Langlois is the Stan Perron Dean of Applied Ethics in the Faculty of Business & Law at Curtin University. He was educated at the University of Tasmania and the Australian National University. Langlois is the author of Sexuality and Gender Diversity Rights in Southeast Asia (Cambridge University Press 2021) and The Politics of Justice and Human Rights: Southeast Asia and Universalist Theory (Cambridge University Press, 2001). As well as being published in many scholarly journals, he sits on the editorial board of The Journal of Human Rights and the European Journal of Politics and Gender.

Access information

The venue is fully accessible. Please contact reception@museum.wa.gov.au if you are attending and would like the organisers to arrange Auslan interpretation.

About In Conversation

A safe house for difficult discussions. In Conversation presents passionate and thought-provoking public dialogues that tackle big issues and difficult questions featuring diverse perspectives and experiences. Panelists invited to speak at In Conversation represent their own unique thoughts, opinions and experiences.

Held monthly at the WA Museum Boola Bardip, in 2023 In Conversation will take different forms such as facilitated panel discussions, deep dive Q&As, performance lectures, screenings and more, covering a broad range of topics and ideas. For these monthly events, the Museum collaborates with a dynamic variety of presenting partners, co-curators and speakers, with additional special events featuring throughout the year. Join us as we explore big concepts of challenging and contended natures, led by some of WA’s most brilliant minds.

Want to catch up? Listen to previous conversations now.

-

Episode transcript

Intro:

Welcome to In Conversation, a series brought to you by the Western Australian Museum Boola Bardip. In Conversation is a safe house for difficult conversations and passionate and thought provoking public dialogs that tackle big issues and difficult questions. Led by some of WA’s most brilliant minds. In Conversation is recorded on Whadjuk Nyoongar Boodja. The Western Australian Museum acknowledges and respects the traditional owners of their ancestral lands, waters and skies.

Anthony Langlois:

Hello, everyone. My name's Anthony Langlois and I'm the facilitator for the conversation that we're going to have this afternoon. I'd like to start just by acknowledging that we're on the lands of the Whadjuk people of the Nyoongar nation and recognize that elders past, present and emerging. And I'd also just like to say about myself, I'm a completely brand new person to Perth. I've been here for about eight weeks, so I feel completely incompetent to be the person who is sort of leading a discussion that is going to be significantly based around the history of HIV, AIDS and relevant communities here in Perth. Most of the people who live in which I haven't met or don't really know anything about, apart from these fabulous people sitting next to me up the front here. Um, So, I'm honoured to have been asked to do this. And it's been a terrific learning experience for me as a new person in Perth to have a number of conversations with these three over the last week as we figured out what we were going to talk about. Please come on in and have a seat. If you if you would like to.

So, let me just tell you who we have here up the front. So next to me immediately to my left, we have Mark Reid. Mark is the founding member of WAAC and has been involved with the HIV response in Western Australia for over 35 years. He was previously employed at WAAC for 25 years in a variety of roles encompassing education, prevention, care and support, as well as fundraising initiatives for WAAC such as Styleaid. Ah. Over his time in the HIV BBV area, he has held several positions at both local and national boards. He was on the board of the AIDS Trust of Australia for seven years and Deputy chair for the last three, NAPWHA board member for ten years and Vice President for three years. Committee member on the Australian National Council on AIDS, Hepatitis and Related Diseases, which was a four year appointment by the Federal Health Minister. Chairperson for “People Living with HIV and AIDS Western Australia” for a year. And a board member for three years. Mark is also the founder and current artistic director of the Pria..Sorry.. Pride Queer Film Festival. So welcome, Mark.

Mark Reid:

Thank you

Anthony Langlois:

Yes, Make him feel welcome.

Audience:

*claps*

Anthony Langlois:

Uh, Dianne Lloyd, further to my left there in the middle in a fabulous red dress.

Dianne Lloyd:

*says something inaudible*

Anthony Langlois:

*laughs*

So Di has been part of Peer Based Harm Reduction since 2009 as community development worker. She is on the Board of POWA Positive Organization, Western Australia and NAPWHA National Associates… National Association of People with HIV-AIDS and also a subgroup of NAPWHA, the National Network of Women Living with AIDS, sorry, with HIV. Dianne was part of the committee supported by NAPWHA to highlight the National Day of Women living with HIV on the 9th of March, which will be celebrating nine years next year. She has been on many panels and presentations over the years, including at the 2019 Australasian HIV and AIDS Conference held in Perth, where she led with a paper or a panel titled Women and HIV. Why are women still invisible? I question we might come back to Diane has been an advocate since she was first diagnosed in 1986 and has been part of many public campaigns, including the latest by WAAC, Step Forward Fight Stigma. Diane is passionate on issues for women and people that use drugs.

And then finally, Rhys Ross is a HIV peer educator for WAAC. Ah, He’s a compassionate and dedicated HIV support worker with experience, providing essential care and support to individuals living with HIV. Passionate about empowering and improving the lives of those affected by HIV through comprehensive support services. Skilled in fostering a safe, inclusive environment, promoting education and advocating for positive living. Committed to making a meaningful impact in the lives of individuals and the broader community.

I'll stop reading now. The rest of this is going to be a conversation. And, uh uh, for myself, I'm a new appointment at Curtin University. I'm based in the Faculty of Business and Law there in a new position, which is Dean of Applied Ethics. And as I said, I've been there for about eight weeks, having come from Adelaide, where I've been living for a considerably longer period of time.

So we're going to have a bit of a conversation this afternoon till about 3:30pm. And I thought I might just start actually since we're sitting in front of this amazing quilt panels by asking each of our, uh, what shall I call you?.... each of our discussants. That sounds a little bit too academic. Each of our speakers, each of our friends up the front here for any reflections that they might have on their knowledge of the history of these quilts or their experience with them, or the contemporary response to them in in an environment that we live in today, which is very different from when the quilts were first called into existence. So, Mark, would you like to, to lead off..

Mark Reid:

Umm, the quilt are complex in a lot of ways, because they really disappeared about five years ago from from being seen by people. And there's actually a procedure you should go through when you're opening the quilts and the way that they're then put away, which is about respecting the names of the people who are represented on the quilts. The first one that's right behind me came from was created by people here in Perth, and it was sent to be part of the Australian quilt. So the Australian quilt, which the Powerhouse Museum holds, which is many, many panels. When it went to the Powerhouse Museum, we asked for this one back, so we had it here so we could display it. And the one behind that is a local one that was created because we wanted to have something that could be shown at different things that we were doing as a community to remind people that whilst we're moving forward, we've lost a lot of people along the way and we need to always remember the people that we've lost. And that was an opportunity for local people who struggled to put the big panels together to do something locally, to remember family members, lovers, friends who died.

Dianne Lloyd:

Yeah, I got here quite early and I'm glad I did because, you know, for the whole week. I've done quite a few events.. and you know… talking and stuff and, you know, I've been all good about it. But then when I came here today and as I said earlier, you know, it's fairly well the only person in the room except for a couple of the guys sitting up and did have a cry. It wasn't just tears, but a cry because for Mark and I, you know that we know a lot of people that are the names on there and we don't just know them, but we know them well. We knew them well. And I was talking to the young girl that was here before and sort of like, you know, a gatekeeper and watching as people came in and giving her the history about it. And I was sharing a couple of the stories about a few people. And I said whilst it's, you know, can be very heartbreaking looking at it, but I was sharing a few of the funny stories of people, you know, of names back there.

And one of them, Luke Coomey, hidden, the one at the back. His crowning glory was his hair. And if you wanted to go somewhere and be there at eight, you were telling Luke that we were leaving at six because if, God forbid, that his hair wasn't right, it would be another shower, wash the hair and redo it again until he was happy with it. So you were hoping on the first round. Most likely wouldn't happen, so you’d be like “oh come on!”. So, yeah, sharing those funny stories. And Mark and I were talking about a couple of guilt trip stories of a couple of people and that. So it does, like, for us because we know people to, you know, remember and share the stories. But for the general public coming in who don't know them personally, but it's a different way, I think, than having just names some where which, you know, and for a lot of the quilt panels and I really you know, some are funny, some are really touching, some are like, you know, they've got their drag dresses sewn to it. And, you know, I've got the best sequins and whatnot, you know. So, yeah, it's a really lovely personal way of seeing people's stories in a very small piece of material.

Anthony Langlois:

Rhys

Rhys Ross:

Hello. Today was actually the very first time I've ever seen the quilts. I've heard a lot about them over the years. I guess for me, I don't have that emotional attachment to the names that are on there. But after seeing the quilt, it does, it does feel a bit more emotional than just going to their memorial at Robertson Park because of the sort of character that you see in the quilt. You sort of get a sense of who those people were, what they meant to their loved ones. Ahhh, so it is it's a very humbling experience because it does actually make me feel very grateful that I didn't have to live through those times, which I'm very appreciative for. But it is very nice to, to be here and see it. You can feel the very like sombre atmosphere that's in here. It's really nice.

Anthony Langlois:

And this raises some of the questions or ideas, I suppose, that we might come back to about the intergenerational experience of thinking about, and living with, understanding HIV and how that interacts with… most obviously with artifacts like these quilts, but also people's relationships, people's working experiences. And, you know, for new people who are, who are coming into awareness around issues, you know, how to how to think about those and so on. So that's a little bit about the quilts and the context we're sitting in here immediately I read out the bios of the three people here, but I thought it would be interesting to get each of them to talk in their own words. You would remember from what I read out that they, they all have these very extensive histories and experiences of, of living and working in the community across intergenerational lines, which is part of what we want to come back to. But I thought I would give just each one an opportunity to talk a little bit about their own work and life experience in this, in this space. And Mark will start with you again if that’s alright. Okay?

Unknown:

*laughter*

Mark Reid:

It's so, it's, it's interesting because I was thinking about this because I don't do it these days because I'm semi-retired. I don't don't talk a lot about the lived HIV experience anymore. And thinking back about the last nearly 40 years of being involved in the epidemic here in Western Australia, it, it, it's interesting to see how far we've come, but how far we've still got to go.

In those early days when we were gathering as a community for the very first time to deal with this unknown virus that none of us really knew how to deal with and having meetings where we had 1500 2000 people in community coming together because they recognized that we had something that we needed to deal with, and we really weren't sure what gay related immune deficiency was going to be all about. And then making the choices we made about getting…. learning about information about safe sex and condom use, but also understanding, trying to understand what the epidemic could potentially look like. And we had these really interesting notions about waves that were going to hit the community and the thousands of people in Western Australia that were going to be infected and affected by HIV.

But the response from the community was so quick, we were so on the ball with it that we were able to stop those waves from happening. We grabbed it, we got the information out there and we took the community on a journey with us to educate them, to inform them, and to let them know about what this new disease was, how we could care for each other, how we could look after each other, about how we could stay safe. Australia was at the at the forefront of needle syringe exchange programs, which again I think saved so many people's lives. Moving forward. But then in those early days, we also had to deal with, with the people that are dying too, which is something which of course we've moved away from now, chronic, manageable illness and we're all getting on with our lives and moving forward.

So those early days were all about how do we educate community, but then how do we care for the people who are unwell? You know, And we did something again in here in Western Australia and it was the WA AIDS Council in those days is we were training people up to create care teams, to look after people in their homes. Because one of the things we did… you know, I remember going to the hospital one of the first times and having to be put in a hazmat outfit to go in to see to hold someone's hand.

And we just went “We need…” it wasn't me. But the boards of of the AIDS Council and community said, “we really need to empower our community to give some dignity to people wanting to die at home”. So they're in their own environment, they're safe, they’re cared for. So we had 24 hour teams, care teams go into people's houses. So they were cooking, they were cleaning, they were washing, they were doing everything for a person so they could come home and have some dignity in their last months, weeks, days, to get them out of that environment, being up at the hospital. There are so many more stories about those early days. You know, we , we had a candlelight vigil started as a great way to remember our community. And we started up at the church. I didn't even know what the church was called.

Max:

St Mary's.

Mark Reid:

Thank you, Thank you, Max. St Mary's. And the reason that we had it there was because up on the ward ten was where all the HIV AIDS patients were, and the nursing staff could bring them on the balcony so they could be a part of the vigil. And those first couple of years we had four or 5000 people, all with candles, all walking all the way to Forest Place, where we would have people talk and lay candles and those sorts of things because we were dealing with people dying. We were dealing with an epidemic that was whilst we were being really good at educating community, we, we were certainly also dealing with, with toxicity of the drugs to start with that made people not hesitant to start on them. But they did start on them because they thought it was the only hope they had. And we also had a lot of ignorance in community. So I remember when a really close friend of mine died and he had lived with his partner for 20 years, but the families didn't know that they were a couple. And so when he died, his partner of 20 years had to walk with us behind, while the family was in the limos and at his funeral, his partner was not mentioned once, and then the family sold the house from under him and he just got a bit of money and was sent on his way.

That's what we were dealing with in those days because we had such ignorance and such naivety around HIV and just even about queer relationships, you know, because people were just not comfortable coming out and add the queer and the HIV, and it created all sorts of problems. So look, I could know, there's a lot of stories from the early days,

Anthony Langlois:

Lots of things to come back to and tease out a little if we have the time. But Rhys, I want to go to, to you next. So we've just heard from Mark, some of this sort of historical context and some of the origin stories and so on. So you're working with WAAC today. So this is sort of bringing in the intergenerational theme that is part of the title of today's talk and some of our earlier discussions. Can you can you perhaps just start by talking about what, what you what you do now in your role and your experience there and as you see fit kind of linked perhaps back to some of the things that Mark's been reflecting on?

Rhys Ross:

Yeah. So I've been a peer worker at WAAC now for just over a year. I guess the reality that the people we support now, the struggles that they're facing a quite different thankfully, the sort of stigma is definitely the thing that links them all together is there still is a lot of misinformation out there and myths, I suppose, about HIV.

I'm very grateful that I've heard a lot of stories from other people, but when you would work with these clients, it would become very overwhelming when they would pass on. I'm very grateful that I have never had to lose any of the people I'm supporting. They're all still with us. The main thing I try and do with them is I just try and show them as much kindness and compassion as I can because I might be the only person that does that for them that week, particularly the people I'm supporting that are from that generation that were diagnosed in the eighties and nineties. We are seeing a lot of social isolation. The, the people that they grew up with are not here anymore and they've sort of been left behind. And so I like to just come in and give them a big smile. The other thing that we're sort of seeing is, I guess with the people that are newly diagnosed, they are definitely sort of managing to get on with their lives. It's not something that they are thinking about too much, but it is something that they are not wanting to talk about. It is, discretion is definitely at the forefront of everything that we are doing. It's… the fear mongering is something that's definitely still stuck around, so that presents its own challenges in a way. We've got to work around that, but we make it work. But yeah, again, I'll probably say this every time. I'm very grateful that I live in the generation that I do, and I was diagnosed in the time that I was because I can't even imagine what that would have been like. That would be absolutely terrifying. And I've got so much empathy for anyone that had to live through that.

Anthony Langlois:

Do you have any more thoughts about, I mean, we have this interesting situation where there's been both social change and change in the medical and technological elements of, of managing illness. And you're working with people, presumably across a range of different age groups who are either being newly diagnosed or who are, you know, have been living for quite some time and perhaps the treatment regiment has changed or the social context has changed, perhaps as a, maybe this is a completely unfair question. But as, as a, as a younger person working with those, how do you, how do you find that interface with the, with the differences and your own experience and the experience of your clients in kind of coming to terms with those differences?

Rhys Ross:

Yeah, for sure. The, the client, the people that I do support that were diagnosed in those earlier days, sometimes, it can take a little while to build that connection, that relationship. There is a little bit of a disconnect because my journey looked very different to theirs. The… what they were facing when they were diagnosed is nothing like what I was facing when I was diagnosed. There can be, a bit of a… I’m trying to think of what the right word would be, ummm, but, ummm

Anthony Langlois:

We are being recorded. But feel free not to be so polite.

Panel:

*laughs*

Rhys Ross:

Yeah, there has been times where I've sort of been made to feel like my hardships are not as valid because my reality is not the same as what theirs was when I was diagnosed. So that is definitely something that we…… But, you know, it's always good to talk it out and I just listen to them and I just make them feel heard. I just try and understand the best I can, everything that they have to say. It is something that I think works…. Um the….. I've even heard from people that were around in the eighties, nineties, that don't live with HIV, they sort of look at people my age that don't live with HIV and are very envious of the fact that we can just have unprotected sex and sort of not have to worry about it because of medical advancements with things like prep. So I think it is…… does work in both streams, I suppose.

Anthony Langlois:

Thanks very much. Di, if I can come, come to you now. And so we talked quite a bit when we were talking earlier about your work with women and in particular, and as I mentioned in the bio, your earlier presentation from twenty-nine about the invisibility of women. Can you speak to that a little bit for us and about the ongoing sort of continuing issues there?

Diane Lloyd:

I just want to backtrack a little bit about when first diagnosed. I, too, are very grateful that if it wasn't for men who have sex with men starting up the AIDS Council, that I wouldn't have had the support that I had. However, I was often and for many, many years the only woman that would be attending different things, whether it be a retreat or the support group or the dinners or whatever, and I would often be mistaken for either one of the other counsellors or a volunteer or yeah, I can remember many stories of like, you know, be lining up to get a meal, “Excuse me, but it's people with HIV first, not volunteers”. And so, yeah, I had to explain that I too….. I just going to say somethings and you said we’re recorded. That I too… that.. people with vaginas get HIV as well. So, which I also had to remind the medical profession about because the questions were often very just generic and never would ask about when was my last pap smear or menstrual cycle questions and all that sort of thing. So yeah, I had to remind even the medical profession that, you know, you need to look at issues specifically for women. Um, I just want to share one really funny story again about Luke at the memorial up at St Mary's. There is us two and another guy who's still around and we were planting a rosebush and somehow…. I'm going to blame it on them… and it really wasn't me, but it caught fire and we were trying to put the fire out with anyb… but without anybody noticing that the rose bush had caught fire. So yeah, so for women… *laughs* Umm I know *laughs*

*Another panellist says something inaudible* so when you were talking about that, I was actually smiling and you were talking about something very serious. And I was remembering that story.

Umm, with um, there was often benefits of being the only woman like going to retreat. I shared this story with… there was one that we were and it was so hot and the venue we were at didn't have any aircon and the guys were all in shared rooms. So I got my own room and then I also got my own fan because I was the only woman there. So there was some benefits. But, you know, and then I'd say, I wish more women would be around. So it's always like, careful what you wish for, because then I had to share all those things. So again, you know, very grateful for, you know, to the gay guys starting up the AIDS councils and the support, because otherwise I wouldn't have had the support that I did either. However that.. for women we were still very much invisible and had to fight for things and to be recognized. And if I heard one more time “but there's only a few of you”, and I said “well you let me know when we get to the magic number for getting support or, a woman's worker or things like that and I'll be happy. But you need to let me know the number, what the magic number is”. And so it went like, you know, today we still got to fight through any support that we need. Um, again, I know our numbers are lower, but we're still here and do have different needs to the rest of the community. Um, the other thing to do, that, well hopefully another 20 years, you're still going to be sitting up here saying, yeah, I'm still carrying the flag. But people like Mark and myself have been doing this work for a very long time. There's not a lot of people that are prepared to stand up and be the face of or the voice of. And especially for women across Australia, there is only a very small handful of people, so we go through that burnout and think like, you know, we want other people to be stepping up. But for women they get on with their lives looking after the children and working and HIV becomes a lot smaller part because they have more pressing issues of like getting the kids off to school. So and as in general, even if, you know, everybody in the family gets the flu, everybody else gets, you know, like the men are dying, you know, I've got the flu. Whereas women, it's just cold, you know, get up and got to do everything else and get on with it. So to have other women to, to be the face and the support has been a fight over the years. And then because you're one of maybe only one or two in the state, not just here, South Australia, Victoria, New South Wales have all had the same thing that you get burn out and you, you know, it's like you want other people to step up, but then it's a guilt trip because I've done it myself. I've stepped back, but then nobody else steps forward.

So you come back again, which is exactly what I’d be doing, what I am doing now, come back home to WAAC to do things for the women's group. So it's, it's the passion, but also the guilt trip do you think? Yeah, a little bit?

Mark Reid:

But it is the passion. I think the reason that those of us that have stayed involved are still involved is because we're still passionate about trying to make the world a better place for people with HIV, trying to deal with the needs that are emerging as we we're becoming an aging community. Seeing that there are still issues that we've got to deal with in 2023, that some of them have… we've certainly moved on, but we're still, there are still things every day that we've got to deal with. And, you know, when I look at at WAAC and look at the complexity now of the clients that they're dealing with, because the reality is 80 to 90% of positive people in Western Australia are now out there in the suburbs getting on with their life. It's really easy. It's a chronic, manageable illness. They can take their medication, they can go and see their doctor every three or six months and they can move on. The majority of them are working or studying or in relationships, having a good old life out there. Hallelujah. We've moved from the days when at the start of the epidemic to now, and we've got so many people out in the community.

And I think that's one of the other reasons why it's tough for us to engage with new people, because HIV is not front and centre for them. It's just part of the picture of who they are. It's one aspect of a bigger picture of a complex human being. And so they are out there getting on with their lives.

So we have this discussion all the time. You know, we have it at meetings and we have it in groups and we have it at board level. How do we engage with positive people? I think a better question is do positive people want to be engaged with? Because if they did, wouldn't they be putting their hand up looking for things from different groups and different organizations?

Diane Lloyd:

I was just going to say that, you know, it's a wave of like the support, like when you first diagnosed, of course you need a lot more support and then you get to a point where you just get on with things and then, you know, there'll be some bumps in the road just as it is for everybody in life.

But the difference between HIV and everything else and Angela spoke of this yesterday is the stigma. You know, other chronic illnesses. I've got diabetes and a whole other list of things as well, that the stigma isn’t attached although, little bit with diabetes because they say

“if you eat properly,” *joke whinging tone*

Audience:

*laughs*

Diane Llyod:

but it's probably not the best of examples, but you know that… it's the stigma that is the difference.

You know, And so I guess that people get to…. for me on, you know, looking at that, I've always been very open. So there's nothing that people can use to throw back at me because if you're open and like, well, it's not going to bother me. It's like, well, I can't really say too much then, but you know, it takes a while for some people to get to that point. Some people don't, you know. So yeah.

Anthony Langlois:

Rhys, can I bring you in there on something that I think Mark said or was alluding to before about the, the relationship between people who are living with AIDS in the community and what we might think of as the activist community or, you know, sort of bodies like WAAC or whatever who are trying to reach out. From your vantage point, both as someone working in one of those organizations, but also as a younger person, Does that sort of chime with you in terms of the way in which people who, who are, just as it were, living in the suburbs, getting on with their lives despite their diagnosis and so on, think about themselves and their lives and the broader social networks that they may or may not belong to?

Rhys Ross:

Yeah, I know that I guess personally speaking, before I started working with WAAC, I had never engaged with WAAC, so I was living positive for about five, six years before I started working at WAAC. I do remember when I was first diagnosed, Royal Perth did offer to put me in contact with a peer worker at WAAC and they sort of gave me a vague description of this person's demographics and my immediate thought was not relatable. I can't relate to this person.

Mark Reid:

Because it was probably me,

Rhys Ross:

probably,

Audience:

*Laugher*

Mark Reid:

and we're just a few years apart.

Rhys Ross:

So that was something for me that was like, I don't think I'm going to see myself there. So I'm, I'm not going to bother. I sort of just seeked out, I guess, counselling through different services. But once, once that initial process was over, I never really, I guess, felt the need to engage because I was literally living in the suburbs, getting on with my life. There was just never, I never felt like there was a need for it. For some people, there definitely is sort of…. like what Mark said, because most people are getting on with the lives of people that we do see engaging, have very, very complex needs that need a lot of support. But yeah, if you are just sort of getting on with your life, your physical health isn't affected, it's not affecting your mental health. I guess you wouldn't feel the need to engage. You don't feel the need to surround yourself with other people who are living with HIV because it's… really …it's not something that, you know, because we're not really going through much hardship because of it. It's not something that fully connects a lot of people any more compared to what it used to be. That's how I feel anyway.

Anthony Langlois:

So. So can I ask then about that

Diane Lloyd:

can I ask… sorry

Anthony Langlois:

You said… Sorry Di, I'll come back to you in a second. But both Di and Mark referred earlier, and this is something that I want us to talk a little bit more about, but referred to stigma and discrimination. But in that scenario that you're describing there where, you know, sort of it is possible for people to just sort of live out their lives in the suburbs or as a we’re of describing it. What do you what do you think people's perception of or experience of stigma and discrimination is then in that context? I mean, from what we've been saying before, it hasn't gone away, but it's obviously being experienced or managed in a different kind of way, to, to, you know, what it was in the eighties and nineties at the beginning of the epidemic and so on.

Rhys Ross:

I think for myself, I'm very open about my HIV status, so no one can really use it against me to make me feel bad. But with other people who are open about it, I don't think they're even opening that door to let any stigma and discrimination in. Whereas if you are a bit open about it, I think the worse stigma I've personally received is probably from medical professionals.

I think it definitely hits very different compared to the everyday person. You sort of have this, it's sort of ingrained into you from a very young age, Doctors and medical professionals are people to be trusted and then so when they break that trust, it cuts a lot deeper. But I know that a lot of, a few of my close friends are similar age to me who are positive, they don't tell their GP when they go. They, if there's anything related to it, they just wait until they go to Royal Perth or Fiona Stanley. They're in.. all the ones I know are in long term relationships, so their partner knows, but they don't feel the need to really tell anyone else that they're involved with sexually. And so it's just a very and because they're undetectable, there is no need for them, for them to tell people it's a very different ballgame now.

Anthony Langlois:

You know, the, the medical and technological differences of… have really significantly change that side of things. But it's interesting the way it feeds back into the social relationships and the kind of siloing or bifurcation and the question about what the… you know, if we if we're thinking about stigma and discrimination, you know, what the impact or experience people would have if they if they were, you know, just disclosing in all those contexts and what that might say about levels of acceptance or understanding in the population more broadly. And I mean, I suppose I might come back to that with you, Di and Mark, particularly in relation to World AIDS Day that we talk about on the 1st of December, which… a significant, a significant part of which is around the education piece and public awareness piece. I mean, how, how do you think that feeds into these questions of ongoing stigma and discrimination? Di? Do you want to?

Diane Lloyd:

Yep, also I want to bring up another point and then I'll get onto that and Mark can follow through. Sorry. I, I said that the problem that you would have is shutting us up. That we've not spoken about a few of the subgroups and especially amongst women, that the only thing we may in common is that we've got HIV. And then you'll have people from the CALD (Culturally and Linguistically Diverse) community, from the African community, from the Aboriginal community, and to be able to try and give support within that as well, because that again brings up its own issues.

Then, the other group that we also haven't mentioned is that men identify as heterosexual, have always been saying, What about us? You know, it's like, where are you going to have to do what everybody else has done? What gay guys have done, what the women have done is start your own group. So it's only a very relatively like recent like support that people have started doing as well.

So for the community and World AIDS Day, because, you know, look, we all know because of funding and the money and everything, but I don't think the general community is aware of things like, U equals U, the changes. It's a chronic illness. I think they are starting to maybe have a bit of an understanding between the difference in HIV and AIDS. But even just that, that simple point, you know, I still hear people use the word AIDS when it should be HIV. And for people like us, that makes a, it’s a really big difference, those two words on how you feel about things and where you see the future and all of that sort of thing. So I think the community, the general community is still very uneducated on changes and there's been so many over the years that they're just not aware of.

Mark Reid:

I think it's also because it's dropped off the agenda. It's not front and centre anymore. You know, in the very early days when we were dealing with people being very sick and being in hospital and in our community, it was very, very visible. You go to Connections and there might be two or three guys on the dance floor with copies of Kaposi sarcoma lesions on their faces or on their bodies and you actually…. HIV was right in your face. In the last 15 or 20 years, HIV has dropped off the agenda. It doesn't impact general community in their eyes. It's not in the newspapers, it's not in the media. So if you're not reminded that something is in community, you're not necessarily going to think about it or engage with it. And so it drops out of people's consciousness and their thinking. And it's not until they're faced with dealing with it that those prejudices and that lack of education come to the forefront and that stigma discrimination plays out. So I think we've been very good. We were very good very early on in educating people, but it's now very difficult to sell a story because we haven't got a death and dying story to sell to the media anymore. They're not really interested. They don't want to have a happy story about, you know, two gay boys living in the suburbs happily living a gorgeous life with a picket fence and a dog and a cat and, you know, getting on with their lives. That's not good front page, West Australian media. They want a hospital bed with an emaciated looking person, taking their last breath, unfortunately. And so we haven't got that as a central plank to be selling to meh…. And that's really sad, quite frankly, because it's the celebration stories of the fact that here we are with a chronic, manageable illness and not a death sentence. So we're able to move forward with our lives and that's what we should be celebrating. But unfortunately, the community doesn't see it.

Anthony Langlois: Rhys does that chime with you as someone from a different generation?

Rhys Ross:

Yeah, I guess, um, like, so I turned 18 in 2014 and I guess by that point it was definitely not at the forefront of people's minds. I do remember learning about, like in high school and I think I would have been 16 when we were doing all this extra health stuff, a little bit more in depth. But when it came to HIV, I did go to religious school as well, but the teachers just sort of said this is something that killed a lot of gay people and, you know, do worry about it, and then showed us the Grim Reaper ad. But really that advert would have been about 25 years old by that point that they showed us that and they didn't really go much more in depth about it. So that was sort of the limited knowledge I had. And even coming out for me, the first thing people did say was, you know, very wrongly, “you'll get AIDS”. And it was like, ummmm, so even then, like the fear mongering was still there and I didn't know the difference between HIV and AIDS. They were just sort of interchangeable for me.

And that was, yeah, about ten years ago. It was only really after I got diagnosed, I actually learned what the difference was. And you know, there is effective treatments. The quality of life is a lot different. But none of that was really taught to us in schools. And considering I wasn't in school that long ago, I think there's definitely still a lot of room for improvement there. Yeah, it's definitely not, umm because yeah, you sort of hear about all these candlelight vigils that Mark and Diane spoke about back in the day where thousands of people would come. I've never really seen any of that. Again, so it just wasn't there for me to see. So it's just not something I thought about at all until I got diagnosed.

Mark Reid:

Look, it's interesting because in the very early days, Di and I, along with Luke Coomey, used to go into public speaking, so we would, we would do regional tours, Wickepin, Darkan, Geraldton, Kalgoorlie, down south anywhere because the AIDS Bureau, that was the precursor to the Health Department response, thought rightly, that putting a face to the epidemic would actually let people understand what living with HIV was all about. And we're fortunate that Luke, Di and I were all comfortable enough within our own skins with our HIV status to be able to go and do that. And it had an impact, you know, because people were engaging with the education, because it would be a facts talk where you learnt about the epidemic and then somebody with HIV would get up and talk about their lived experience. And putting a face to an epidemic has an impact on people, which is why the current campaign that WAAC have just done, which is about trying to reduce stigma and discrimination, I think is going to be so successful because it puts a face to the epidemic again. And what it's doing is it's educating community to understand that HIV, these days is just like any other chronic, manageable illness. Hallelujah. We've got to that stage, but we've got to maintain that to keep engagement with community, to let them understand the issues that are still around. Now, you know, because we've done enough of the going to schools talks, really, you know, and we used to do weeks of country visits to things, the three of us. And whilst that was successful then we've moved past that now. And you know, we've got to look at things differently.

Anthony Langlois:

Yeah, it's a really, really interesting kind of development. The, the impact of the, combination of the, you know, the change in medical treatments, the changing broader social attitudes and this kind of intergenerational changes so that the community is actually a bigger and different community to what it was originally. And then the ongoing challenge I think. Um, might be a good point for us to open up to the community that we have here in in the room. We've got about ten or fifteen minutes left. So if people would like to ask some questions, I'm not sure if we have a… yes, we do have our roving microphone. If I can just remind people that we that we're being recorded. So please be aware of that in what you're asking. And we have a question down here at the front. Thank you very much.

Maxine:

Question, who knows? Might be more than a question. I'm Maxine. One of the things I one of the reasons I think we still do this is because we know that holding a secret inside yourself is damaging. Yeah? That to be able to be open is, is liberating. And that the reason we need WAAC is that at least if people can know, they can go to one place, that they can feel some safety and security and you're, you're the embodiment of that. When you go into their homes, you might be the one person I think I can let this drop. I can let the, the, the, the, it drop. Because we know we know that there's, you know, gay AFL players out there that aren't coming out. So we know the damage of, the harm that a secret can do and the and the stigma internalized which can, can, become toxic. So, thank you for doing it. Thanks for showing that you can live, you know, you can live publicly, with it. But, I think the liberation that comes from being able to be open, you can't even put a price on it, can you? Can you Rhys?

Rhys Ross:

Not at all.

Maxine:

It's gold, to work at a place like that. It gives you a bit of cover. You know, you can sort of. Yeah. Let it out when you do and when you don't. But yeah. To, for you to be going to people's homes and giving them at least one safe person that they can be free with I think is absolutely beautiful. So thanks for doing that.

Rhys Ross:

Thank you.

Mark Reid:

It's what WAAC's been so good at from the very beginning. It's engaging with community and being with people. You know, I know that work currently has sixty-three clients that they’re seeing regularly. That's a huge caseload for only four or five workers to actually be there to hold someone's hand. Whether it's about care and support or whether it's about having a listening ear and peer support. Whatever it is, that’s a huge difference. It's keeping people well, it's what it's doing as well. Because you're right, the facade drops and they can just be themselves maybe for that one hour a week when they're with somebody that has the ability to just be there for them in their wholeness in who they are. I just want to tell a Luke story, too,

Audience:

*Laughs*

Mark Reid:

Because the interesting, the interesting thing. Way back when, when my daughter was born, the midwife assistant was Luke Coomey.

Diane Lloyd:

Really?

Marke Reid:

You didn't even know that, did you? So the person who taught me how to bathe my daughter when she was born was Luke. And then a month later, we were doing talks together. Small…. Just a just a bit of an aside. Small world, but, you know. Yeah, Yeah.

Diane Lloyd:

I just wanted to say that for people in the room and a way for you to, like, you know, have a small window to how we have felt over the years, the stigma and discrimination, is COVID. It brought up a lot of issues that we went through and I'm talking about when it really first hit and there is the fear of like people wearing the mask, not wanting to, you know, if somebody sneezed, you'd be like crossing the road and all that sort thing. You know, we really did live through those things. So, for when COVID hit and all that started, it actually brought up issues for me because my CEO said, “I want everybody to have your own cup and, you know, knife and fork and all that at your desk.”

And all that. You know that because of COVID and that wasn't a joke. We, we had families that made us have our own cup and knife and fork and would be washed separately and all that. So yeah.

Mark Reid:

I remember when I started work at the Attorney-General's Department and they found out that I was a homosexual before I walked in the door in my apricot ensemble on the first day and within three days they had changed the policy on how lunch was done and how the room was done, and I hadn't even come out of as HIV positive at that stage, even though I was fairly well known in Perth as being openly positive.

But everybody was told to bring a cup in from home and that was the cup they had to use. There were times when you could use the microwave to heat your lunch up and there were specific shells on in the fridge that I could put my food on. And it was like that basically for the whole time that I worked at the Attorney-General's Department.

So exactly right. COVID It brought a lot of that stuff back to the forefront of those days when we were dealing with all of that fear. You know, that was happening in community about not knowing how to deal with us.

Anthony Langlois:

I think part of what's interesting about that too, is that, I mean, COVID is still with us, and in many parts of our society, there is a there is a preparedness, though, to pretend that it has gone or to not want to, you know, face the consequences of how we continue to live with it. I think my personal views about it would be that notwithstanding the success in managing the pandemic, there are enormous failures in the educational piece, in the health management piece and so on, at the national level. And the difficulty in having ongoing public conversations about these, I think is also something where there's an interesting parallel with the, some of the things that we were saying earlier about the way in which, you know, people just get on and live their lives in the suburbs or whatever, because we can now manage it. We don't actually need to talk about it or we don't need to, to come together and think about the consequence of it in our silo, our relationships, rather than sort of break down the barriers between our relationships.

And perhaps that's also reflected in your observation, for example, about, you know, gay AFL players or other elite sports persons and so on, many of whom in a social location would be in a very different kind of position to the kind of people who Rhys was talking about working with, who are often, you know, sort of the most marginalized and, least privileged people, but probably not always, but some of them. And so we have this, you know, complex situation where you have people who have, you know, are in receipt of very generous salaries, you know, high public profiles and so on, who are still unable to, you know, sort of participate in a public conversation or perhaps even in their personal lives, in relationships and so on around this. So it's a very complicated kind of pattern that we still, that we still face. And those questions about stigma, stigma and discrimination sort of intersect with that at every point. I think. Other questions from the floor perhaps. Up of the back there, please?

Guy:

Hello, Um, my name's Guy. Um, I run with some other people, a whole committee called West Pride Archives. Um, I also am the admin person for a Facebook group that's been going for ten years called Lost Gay Perth. So there's um, and there's also another group called Campaign of Moral Persecution Re…Reunion Group as well. So I came back to Perth about ten, twelve years ago and it was a very different city then. It was quite dead to be quite honest, and it's changed quite radically in those 12 years. And I was looking for my history and so it took me ages to find this archive called the Gay and Lesbian Archive WA, and I eventually did gain access and now I'm the Co-Convenor along with Graham is the Treasurer and a really great committee. There's seems to be like a huge amount of cultural slippage in our community. It seems to have a ten year cycle maybe?

It was really interesting listening to Rys talk about your experience and only ten years ago and not having any knowledge of the candlelight vigils that occurred about the hu.., the huge amount of loss that the community experienced. And so it's, I think I've got the answer to the question, but the question is, is how do you connect the younger generations with the previous generations experience? Because it’s,,,, how I see is that there's like ten years, there's a new generation comes up. A friend, Strykermeier, some of you will know, will know him. He's a, a gay man, a queer artist, openly HIV positive. He actually put a post up yesterday, and it was about the names of people who had died from H.. from HIV and AIDS. And the response was incredible. There was, I think there was about a hundred and fifty people listed there and yeah, it was incredible. And we've kind of seemed to have lost our cultural practices because that was, it was called, The Named Project”, and that was a practice that we, that used to occur. I'm not sure if it still does, or, but yeah, and so the names of all the people would be called out, would be spoken to keep them alive. Yeah. So I think we...

Yeah. So the question is how do you, how do you, kind of, I think I know the answer. But how do you connect the younger generation with the older generations experience without traumatizing them and without making them, you know, making them feel bad that as Rhys, you explained, you know, it's such a different experience becoming HIV positive now compared to 20 years ago.

Anthony Langlois:

Can we, can we go to you on that first Rhys?

Rhys Ross:

Yeah look, It's a really good question. And if I had the answer, *Laughs*. But yeah, it can be a bit of a jarring thing when you when you do meet with people that were diagnosed with such a big age gap. Because I, as heartbreaking as I find that their journey and their experience, I don't really relate to it.

And so finding that connection can be difficult. But it's, you know, it's one of the things you've sort of got to look past. There's more to this person than they've just got HIV. There's more to me than that, I've just got HIV and you can just find other ways to connect. And I just try and show them as much compassion and empathy as I can.

Anthony Langlois:

Rhys, can, can I ask on that? So you're talking about the person, which is really, really important. But the other part of Guy's question is kind the broader community historical kind of knowledge and awareness. So can I can I ask you, when you started thinking about these things in your in your own life and your own experience. I mean, did you have any awareness of a sort of a broader community here in Perth or any idea how you would, or even any interest perhaps to how, how you connect to those historical stories or, you know, beyond actually meeting with particular individuals.

Rhys Ross:

Not particularly. Umm.

Guy:

Theres a real parallel, between how HIV hasn’t become a, has, is not a death sentence anymore and how, um, we have gone through decriminalisation, and marriage equality. And so the newer generations, don’t understand what… the struggles, and the rubbish and the crap and the hatred and the violence and everything that we had to experience. Well, not everyone experienced, but many people did. So they kind of take it.. I don’t want to use the word, but they kind of don’t see it. They don’t see the struggles and good on them you know, it would have been amazing to not have to go through that.

Mark Reid:

But we haven’t been very good as a community of keeping that history alive either.

Guy:

Exactly, Exactly,

Mark Reid:

When Maxine and I were part of a long table discussion a couple of years ago at the art gallery, you were there I think.

Guy:

Yeah I helped…

Mark Reid:

And it was an incredible discussion but one of the things that became really apparent to me was, our early history…. there were people around that table who thought that queer politics and activism started with the, with the start of the Pride committee which is so totally wrong. It was much much further before then. But we haven’t been very good at seeing our history, documenting our history, and then telling people our history. It’s like young queer people don’t understand the whole queer movement and where it came from and the history of it. And we’ve gotten to decriminalisation and marriage equality and all these incredible things but they forget the struggles we had to go through to get to this point.

And so rightly or wrongly, they’re focused on moving forward and see , seeing that we’re in an incredible opportunity moving forward with our lives, forgetting the struggles we’ve now got with trans folk and the trans community right now. But we’re st.. you know, they’ve lost all of that and I think it’s the same with the HIV-AIDs epidemic. You know, we haven’t as a community been very good at documenting our history, of what we went through to get to where we are now. And with the incredible increases in medical knowledge and treatments and, you know, now going into injectables and the notion of potentially only having to have two injections a year and that’s your treatment. You know, hallelujah and look at where we’re going to. It just means that chronic manageable thing the focus for people and we forget where we’ve been.

Guy:

So that’s, that’s some of the work that I and Graham and the other committee members are doing with West Pride Archives. We’re try… we’re making sure that all of that history is found and put into one place and we’re also.. I mean I’ve been researching the Perth community for the last eight years and um, the first response was actually from, “The Campaign of Moral Persecution”. They were the first group who went… I think it was eighty-two, when they put out a leaflet, a pamphlet for this new disease out, and there was no name for it at that point.

Anthony Langlois:

So that, that’s a terrific resource that is being produced, and the work that the Pride Archives are doing. I’m just mindful of the time and if there are maybe one or two other questions. I don’t, I don’t know if one of the things the people in the audience has observed about the people up the front here is that we have two generations, a young, a very younger one and an older gen.. an older generation…

Mark Reid:

Thanks! Old! Thanks!

Audience:

*Laughs*

Anthony Langlois:

I don’t know if there is anyone in the middle who might like to ask a question or make an observation um, before, before we go to the next questioner I’ve noted. But, umm, No? Ok Graham is it?

Graham:

Thanks, Thanks, I’d just like to talk about education, peer education and go back to that subject. I lost my partner about ten years ago and Mark may remember, the AIDs council was running wonderful education programmes for “MSM” in those days. Well, I just want to thank you for that because being in a long-term relationship, I’d never been out in the community, and that was just a fantastic experience for me. And, erh, thankyou WAAC for that. And I’m still friends with many men from that period and who are equally grateful. The other point I want to make is about education, umm, and PrEP. Do you know that so many men still believe when you say you’re on PrEP, that you have HIV. Even my GP, when I told him I was on PrEP, did not know the difference and, so, there is this massive ignorance still in the community and WAAC, you, you, as you mentioned Mark, you still have a long way to go.

Mark Reid:

Yeah yeah, look, the whole.. thank you for the stuff around the workshops. I think that one of the significant things from a very early time until probably five years ago, when WAAC stopped doing workshops, was, if you’re a certain age and you’re queer in Perth, you’re limited in how you can engage with community. We’ve all go these apps on our phone where we can connect with people but that’s not for social outings. That’s for one thing and one thing only, that’s for sex. So the ability to do workshops that were connecting people who had found themselves isolated and alone, and this is not people with HIV, this is just people who are queer. So we ran a range of workshops, “Men on Men”, “Nitty Gritties”, “Loving Our Way”, which was about relationships that enabled people to come together and learn, educate and get support. And I know, like you, people who had, have done our workshops, who are still in those friendship networks today because it enabled them to connect with community. Because they were of an age where they didn’t want to Connections, or the Court Hotel. They wanted to be able to connect with other human beings.

PrEP has, is an interesting thing to add onto the end of that because, a lot of community, is a… One of the things that I’ve noticed with PrEP is that HIV negative men are using it as an excuse to still not have sex with HIV positive men. Even though HIV positive men with an undetectable viral load are much safer to be having sex with then somebody on PrEP. That’s fine, people are still choosing. In the old days we used to call it serosorting. They’re still choosing to.. who they want to have sex with, absolutely, and that’s everybody’s choice to do. But, the information and the education whilst its getting out there, I think what gets lost, especially with GP’s is and having talked to a couple of doctors is, they get bombarded with new information every single day about things and there are only certain things that they stay on top of and things fall through the cracks. And its not until someone comes in and says “Hey I’m on PrEP”,

That the questions, and the, and then they’ll hopefully then go find the answers to be able to then work with the rest of their client base on giving them the right information about PrEP and what its all about.

Anthony Langlois:

Thanks, thanks very much. Look we are out of time uh. I thought we’d just close of, I just give each, each of the panellists a chance to say one more thing that you might like to think and perhaps is the provocation from, from my point of view is, sort of, looking forward um, both in your, ah, you know, your social networks and your, uh, professional networks uh, in relation to these questions. What do you, either what, what do you hope for or what do you think is the most important kind of next steps that we can take as a shared community addressing living with HIV. Di do you want to go first?

Diane Lloyd:

*Says something inaudible*

Anthony Langlois:

Or you… no? No? *laughs*

Mark Reid:

I…

Anthony Langlois:

Mark can go first.

Mark Reid:

I’ve always got something to say. Look I think…

Anthony Langlois:

*laughs* Rhys prepare yourself.

Mark Reid:

I think, sti.. stigma and discrimination are central. I think that one of the things we need to deal with is the criminalisation of HIV. That’s what we’ve got to deal with. And I think that moving forward, we’ve got to look at the laws and how they’re written. And we, and luckily, the new HIV-AID…. National HIV strategy has just been launched and one of their central themes is around decriminalisation and finally recognising that such a huge proportion of positive people have an undetectable viral load so are not a risk to the community anymore. And we need to bring the laws in line with that. And that’s something central that I think we need to do moving forward.

Anthony Langlois:

Thanks Mark. Di

Diane Lloyd:

Ok I might just talk specifically on women’s, um, issue then. I’m really pleased that things have changed where women, um, can have children. Oh, you’ve always been able to have children. But the risk of, of, you know, like, passing it on from mother and baby. Um, and also just from the Queensland conference a couple of weeks.. a couple of months ago that its now acceptable, um, for women to breastfeed their children, um, which was a really, you know, huge, um, step forward. So we keep on saying that there are, you know, huge steps that are happening but we still got other, ah, things that we need to, um, keep on working on. The stigma, discrimination is still out there and I experienced it just very recently myself and had to educate, again, the medical profession. Um, and yeah, all we can do is.. hopefully be an example for our young ones and to keep it going, you know, to keep the education, the support and, you know, to, we want you to take over. Yeah, yeah.

Mark Reid:

We do need to absolutely retire.

Diane Lloyd:

Yep *laughs*

Anthony Langlois:

Rhys, its over to you then. *laughs* you get the last word.

Mark Reid:

No pressure

Diane Lloyd:

No pressure

Rhys Ross:

I just want to say I am very grateful for people like Mark and Diane who have advocated since the very beginning. Because if it wasn’t for people like that, there might have never been the medical advances that we have gotten, the community perception, and I wouldn’t be able to live the life that I do now without people like these two. So I’m very grateful for these two, I’m so glad I got to meet them. I would also sort of second what Mark said about the decriminalisation. That’s something that I definitely think should be pushed more going forward. And I would just want to see more education still on HIV. I see it every day with people I support, they are running into people that have made them feel stigmatised or discriminated against them and its purely coming from a place where that person that’s done that to them is just misinformed. And so there’s clearly still a lot of gaps where education on HIV is just being missed and I think it starts closer to the top, like, the medical teams and then it sort of trickles down from there. Um, that’s what I would like to see moving forward.

Anthony Langlois:

Great, thankyou very much. So yes, can you join with me in, in thanking Mark, Di and Rhys for a really interesting conversation this afternoon. And thankyou all for coming, ah, to support events like this and please take some time as, as we close to take a look at the quilts, ah, that are here on, on display and, and talk amongst yourselves and, um, thankyou once again.

Outro:

Thanks for listening to In Conversation. Brought to you by The Western Australia Museum Boola Bardip. To listen to other episodes from this series, go to https://visit.museum.wa.gov.au/episodes/conversation where you can listen to a range of talks from past and current seasons of In Conversation and more. In Conversation is recorded on Whadjuk Nyoongar Boodja. The Western Australian Museum acknowledges and respects the traditional owner of their ancestral lands, waters and skies.

More Episodes

Meet Professor Kliti Grice, the West Australian Scientist of the Year 2022, as she embarks on a quest to decipher the Earth's past mysteries.

Join a panel of featured young LGBTQIA+ writers and storytellers as they delve into the fantastical realms and real-world struggles of the exciting new anthology, An Unexpected Party.

Explore Australia's dinosaur legacy with Dr Stephen Poropat as we better understand the science behind the scenes of Australian palaeontology!

As we inevitably move towards cleaner, more sustainable forms of energy, how will a shift away from traditional mining practices transform this economy? A panel of experts explore the implications of this shift with a specific focus on how we see ourselves in a world that increasingly demands environmental responsibility.

Join Megan Krakouer, a prominent Aboriginal leader, as she discusses the nuances of her surprising change of heart on the Voice to Parliament — just a week before the referendum.

Join host Michael Mills in a captivating live recording of the Palaeo Jam podcast during National Science Week!

As AI rapidly evolves, join our panel of experts in an exploration of these complex issues, including how we can harness its power while ensuring responsible and ethical use before we're outrun by its speed.

Do you know how and why your teeth do what they do? Find out all there is to know about teeth sharpening.

Decoding the language of our written and oral histories in Australia.

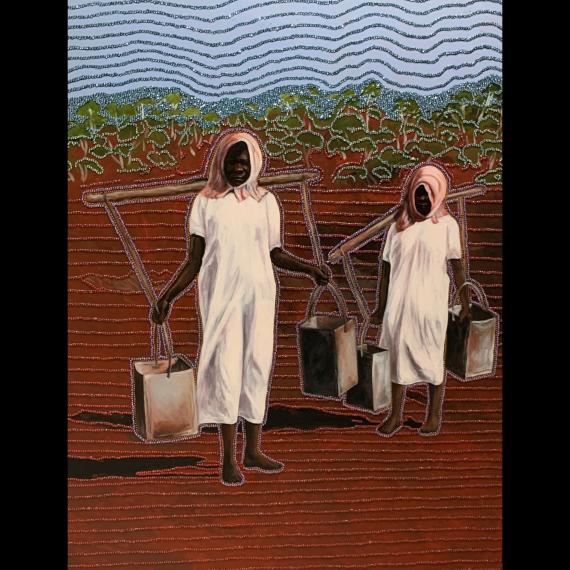

Join us for an insightful talk with the esteemed Professor Henry Skerritt, as he takes us on a journey exploring the captivating art of Jdewat/Ballandong artist Meeyakba Shane Pickett.

No, it’s not a card game but a community initiative helping us further our knowledge of a group of endemic land snails Bothriembryon affectionately called ‘Boths’.

Delve into the way Aboriginal industry professionals are shifting representations, decolonising the media space and creating visibility for Aboriginal people in the industry.

Exploring the debate surrounding the establishment of an independent, representative advisory body for First Nations people.

Aristeidis Voulgaris sharesstories from his eclipse chasing travels and discover the complex instruments and tools used in solar astronomy.

Join a panel of experts and community as they investigate the nature of queer bodies, and queer sexuality, in public space.

Join historian Toner Stevenson and astronomer Melissa Hulbert, as they share their tips on how to salute the sun during this eclipse!

Simon Miraudo and Tristan Fidler from RTRFM’s ‘Movie Squad’ are joined by Chelsey O'Brien, Curator at ACMI, as they review and discuss Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland as a foundation for contemporary storytelling in film.

In this one-off Perth Design Week talk, the Museum celebrates the remarkable women in architecture and film in a panel discussion, recorded as a part of its recent award-winning film screening.

Join world expert Dr Chris Mah from the Smithsonian Institution as he recounts his encounters with some of the most unusual creatures on the planet.