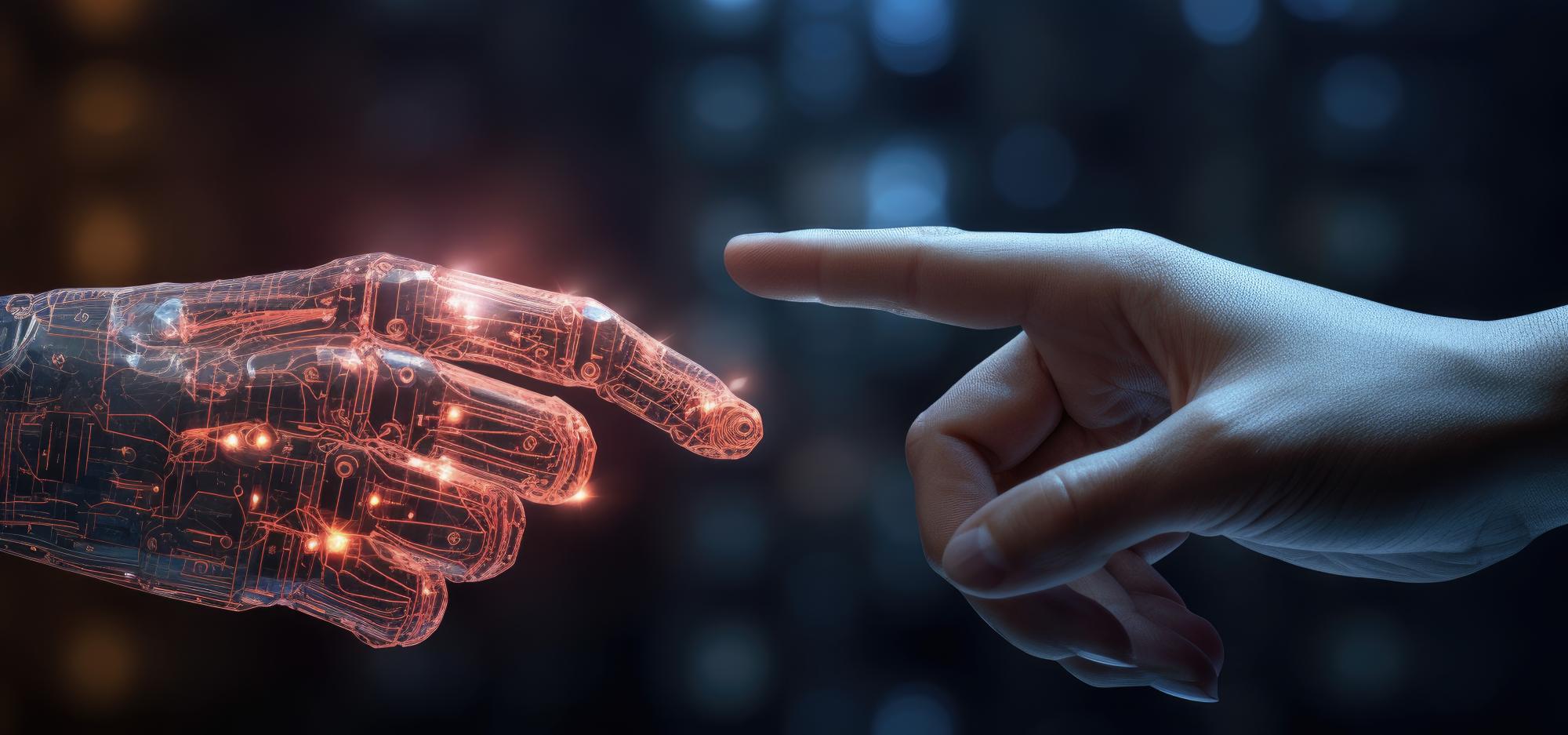

In Conversation: The rise of AI

Explore the potential of AI with an expert panel as they examine the benefits and risks.

AI technology has the potential to revolutionize our world with its promised benefits of personalized medicine, workplace efficiency, and autonomous vehicles. However, it also poses significant concerns such as perpetuating biases, displacing human workers, and spreading misinformation.

As AI rapidly evolves, join our panel of experts in an exploration of these complex issues. We'll discuss how we can harness its power while ensuring responsible and ethical use before we're outrun by its speed.

Meet our Facilitator

Ben O’Shea hosts The West Australian’s flagship news podcast, The West Live. Before that he was editor of Inside Cover, and currently also writes a weekly NFL column for The Sunday Times, hosts a movie show called Reel Talk and regularly reports on science.

Meet our speakers

Ajmal Mian is a Professor of Artificial Intelligence at The University of Western Australia is a renowned scholar with numerous achievements. He has received three esteemed national fellowships, including the 2022 Future Fellowship award from the Australian Research Council. As a Fellow of the International Association for Pattern Recognition, a Distinguished Speaker of the Association for Computing Machinery, and President of the Australian Pattern Recognition Society, his expertise is widely recognized.

Ajmal Mian has been honoured with awards like the West Australian Early Career Scientist of the Year (2012) and the HBF Mid-Career Scientist of the Year at the Premier’s Science Awards (2022). He serves as a Chief Investigator on various AI research projects and an editor for multiple scientific journals. He has supervised 24 PhD students to completion and published over 270 scientific papers.

Oron Catts is an artist, researcher and curator who is Co-CI with Sarah Collins on the ARC project 'Cultural and Intellectual Histories of Automation'. His pioneering work with the Tissue Culture and Art Project which he established in 1996 is considered a leading biological art project. In 2000 he co-founded SymbioticA, an artistic research centre housed within the School of Anatomy, Physiology and Human Biology, The University of Western Australia.

Under Catts’ leadership SymbioticA has gone on to win the Prix Ars Electronica Golden Nica in Hybrid Art (2007) the WA Premier Science Award (2008) and became a Centre for Excellence in 2008. In 2009 Catts was recognised by Thames & Hudson’s “60 Innovators Shaping our Creative Future” book in the category “Beyond Design”, and by Icon Magazine (UK) as one of the top 20 Designers, “making the future and transforming the way we work”.

About In Conversation

A safe house for difficult discussions. In Conversation presents passionate and thought-provoking public dialogues that tackle big issues and difficult questions featuring diverse perspectives and experiences. Panelists invited to speak at In Conversation represent their own unique thoughts, opinions and experiences.

Held monthly at the WA Museum Boola Bardip, in 2023 In Conversation will take different forms such as facilitated panel discussions, deep dive Q&As, performance lectures, screenings and more, covering a broad range of topics and ideas. For these monthly events, the Museum collaborates with a dynamic variety of presenting partners, co-curators and speakers, with additional special events featuring throughout the year. Join us as we explore big concepts of challenging and contended natures, led by some of WA’s most brilliant minds.

Listen to previous conversations now.

-

Episode transcript

Ben O’Shea: In Conversation takes part on Whadjuk Nyoongar Country and we would like to acknowledge and pay respect to the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we gather this evening, and we pay respect to their Elders past and present. And I'd like to extend a special welcome to any First Nations people here with us tonight.

Okay, if this is your first In Conversation at the Museum, let me tell you what you're in for. It's all about starting thought-provoking public dialogues to tackle big issues and difficult questions featuring diverse perspectives and experiences.

We'll explore big concepts with the help of some of WA’s brilliant minds, and you'll get to ask them some questions.

And now, AI has been around longer than you might know—and we're going to get into that soon—but it's really become a hot button issue since the exponential rise of ChatGPT.

And I've got a confession to make. I've never used ChatGPT before yesterday. I'm a journalist. It's kind of a bit of a sore subject: something that comes along that can write stories in a second.

So, I've never used it, but I figured I probably should have a look so I'm a full bottle tonight and so I asked it to write my introductory remarks.

These ones so far have been ones that I've written myself, but I gave it a prompt to: “write a speech introducing Perth journalist Ben O'Shea in the first person, to be spoken at a public forum about the benefits and disadvantages of AI in a humorous tone in the style of an inspiring keynote address by Steve Jobs.”

Because, apparently, you've got to be really specific when you're prompting AI if you want to get a good output. And so, this is what it says.

“Hold on to your kangaroo hats—”

<audience laughter>

“—because we're about to embark on a ripper of a journey through the highs and lows, and a few cheeky chuckles, of the AI world.” Not sure what a kangaroo hat is. “We're diving deep into the AI ocean and I'm your snorkel-toting tour guide. Crikey, if this doesn't feel like crossing Sherlock Holmes with R2-D2 I don't know what does.” I can honestly say that I don't think my puny human brain could come up with that metaphor, but let's keep going.

“Get ready to laugh, ponder, and maybe even shout, ‘Oi, that's bonkers!’ It's time to strap in, hold on to your Vegemite sandwiches, and let's kick off this AI adventure.”

So, there we go. Folks, can we hear it for ChatGPT?

<audience applause>

So, it is, yeah, <laughs> it is bonkers. And I also thought, to just complete the complete the vibe I'd get an AI image generator to come up with an official headshot for me. And if we can cue this—

For some reason, this particular AI image generator imagined me as, ah, some sort of space cyborg. Extremely more handsome than I actually am in real life. So, you know, all of a sudden AI is looking pretty good.

But thankfully, we don't have to rely on ChatGPT to unpack AI. We've got some very human experts who are sitting patiently beside me, and I'm going to introduce them to you now. Next to me is Ajmal Mian, a professor of artificial intelligence at the University of Western Australia. He's a renowned scholar with numerous achievements. He's received three esteemed national fellowships, including the 2022 Future Fellowship Award from the Australian Research Council.

Ajmal is a Fellow of the International Association for Pattern Recognition, a distinguished Speaker of the Association for Computer Machinery, and President of the Australian Pattern Recognition Society.

Ajmal has been honoured with awards like the West Australian Early Career Scientist of the Year in 2012 and the HBF Mid-Career Scientist of the Year in 2022. He serves as a chief investigator of various AI research projects and an editor for multiple scientific journals.

He’s supervised twenty-four PhD students to completion and published over two hundred and seventy scientific papers. Presumably without any help from ChatGPT.

Ajmal Mian: So far.

Ben O’Shea: So far. <laughs> Can I get a warm welcome for Ajmal Mian?

<audience applause>

And now, originally, and probably when all of you bought the tickets— We were supposed to be joined by Associate Professor Sarah Collins, but she had a health emergency in her family today, and so our thoughts are with her tonight. But we're very lucky to have such a distinguished last-minute replacement in Oron Catts.

Oron is an artist, researcher, and curator who was co-chief investigator with Sarah on the ARC Project, ‘Cultural and Intellectual Histories of Automation.’ His pioneering work with the Tissue Culture and Art Project, which he established in 1996, is considered a leading biological art project.

In 2000, he co-founded SymbioticA, an artistic research centre housed within the School of Anatomy, Physiology, and Human Biology at the University of Western Australia. And, under Catts’ leadership, SymbioticA has gone on to win the Prix Ars Electronica Golden Nica Award in Hybrid Art in 2007; the WA Premier Science Award; and became a Center for Excellence in 2008.

He and his colleagues won the 2023 Award of Distinction in Artificial Intelligence and Life Art at Prix Ars Electronica 2023 for their artwork, ‘3SDC’. Folks, can you put your hands together for Oron Catts?

<audience applause>

And now, I think, before we start, I hinted that AI has been around for a while, maybe longer than a lot of us realise. So, I think, Ajmal, maybe you're the best person to give us a background on what exactly AI is?

Ajmal Mian: Maybe not the best person, but I'll give it a shot. You know, there's so many different perspectives of AI and so many definitions around, but I will tell you that the main driving force between artificial intelligence is the artificial neural networks, which are based on neurons, which is a very simple mechanism that mimics the biological neuron.

And all it does is addition and multiplication, followed by nonlinear function. So, this simple functionality is then repeated millions of times, and it connects the input data to the outcome that you want. For example, if the input data is a question that you ask ChatGPT and the output answer is something that it should produce.

Now, when you pass this input data, to start with, it will produce rubbish and then you compare that rubbish with what you expected to output and then you back-propagate and adjust these additions and multiplications so that it will produce what is expected out of it.

And you repeat that millions of times again with lots of lots of terabytes of data, and in this process the neural network learns, or is trained to perform, what it is expected to perform. And that's how artificial intelligence works. And what really gave it the breakthrough is self-supervision.

And, in its simplest form, self-supervision is auto-completion. So, you give it part of a sentence and ask it what should be the next. And because you picked it out from maybe a novel or maybe somebody’s writing, so you know what is next, and you put that at the end. And it produces something and it is not right, and it back-propagates and learns.

Or, you hide a part of an image, you feed the image through it and it produces something output, and then you adjust it so it learns. So, self-supervised learning combined with artificial neural networks is really the driving force behind AI.

Ben O’Shea: And can you give us an idea of some examples of AI in everyday life? Like, ChatGPT is the one that's getting all the headlines at the moment, but it's a part of our lives in other ways as well.

Ajmal Mian: Well, when you're using your mobile phone, you know, you get these ads. They are optimised for you because they are using AI. That's one example. And, ah, other examples are your, say, the calculation of maps, you know. When it tells you the route. That’s another example. And a lot of these image editing tools. They kind of had, you know, a little bit of AI in them already.

On all these other voice processing and— It’s kind of a little bit difficult for me to find, you know, easy examples. I don't want to make it too technical.

So, everything that you have been doing on your computer has had a little bit of AI behind it and only ChatGPT kind of made it a 'wow’ factor. So, now you see a lot of text being produced that is completely, you know, AI-generated and images that are completely AI generated.

So, it was there even before you were using it, in the form of your mobile phone, in the form of, you know, like Netflix. You get different sets of recommendations from the other person. And that’s also AI-based. On YouTube and so on.

Ben O’Shea: Yeah, I've seen that first-hand. Like, my partner has very different viewing tastes to me on Netflix and it's completely stuffed up the algorithm. It's, ah, I can’t really even watch Netflix anymore. And Oron, what does— What does AI mean to you?

Oron Catts: Right. That's an interesting question. First of all, I suppose we have to think what intelligence means for us. And I think that we have a very limited, usually very limited understanding of what intelligence is, which is very human-biased in the sense that we think that the way we think about the world is the only form of intelligence.

And one of the issues I feel around artificial intelligence is this wish and attempt to make machine think like, think like us. And this is something I don't think we'll ever be able to achieve.

No, tech— You know, when you see animals as, animals that are doing things and calculating things much, much better than we do, but we don't consider them to be intelligent. So, for me, it's like this vague promise of a smart environment around us that is kind of going to force us to somehow do the biddings, to a large extent.

Ben O’Shea: We'll get onto the existential threat level later, because I know that's the one that people really want to know about. And Ajmal, how intelligent is AI? Like, is it as— Will it, can it get as smart as us? Is it as smart as a dog? Is it as smart as a ten-year-old? Like, is, can you quantify how smart it is right now?

Ajmal Mian: Well, in simple words, artificial intelligence is dumb. It is not as smart as a dog. It is not even smart as a ten-year-old. And, you know, you can— Maybe it's not even as smart as an ant or as a dragonfly. You know, the task that they do for what is important for their survival, it's much more advanced than what artificial intelligence can do.

But artificial intelligence are basically, you know, small pieces of models designed to do a very specific job. And only recently with ChatGPT kind of large language models, they've been connected so that you can do multiple tasks, like, ah— Auto GPT that will take a high-level task from you and then will probe different AI models to do these tasks.

So, in my opinion, it is not really intelligent. It's just sort of doing a very, very specific task in a very sort of well-defined, constrained environment. I can elaborate on the language part if you if you want.

Ben O’Shea: We'll get on to that, for sure. And so, if— So, Oron, so if artificial intelligence is not as smart as we think, but it can do some things very well; it can take an ordinary looking man and make him look like an extremely handsome space explorer. As someone who is an artist who's won awards for cyber art, are you concerned that AI will encroach on the artistic process?

Oron Catts: Not that concerned, because, you know, artists throughout history were relying on different types of technologies to enhance their abilities. So, I don't really see that as a major threat.

I think, you know, as long as there's a human actor in the process that makes the choices, and the choices can be, you know— I'm sure you got about at least ten different options and you chose the one that makes you look good. I'm sure there were others that—

Ben O’Shea: No comment.

Oron Catts: <laughs> So, you know, as long as you're the one who's making the choice—you're the curator, you're the one who's actually deciding what is going to be viewed—I don't really see the artistic process being harmed significantly by that.

And the fact is that, yeah, it is— Obviously, there’s art that is based on skill and craft and that's a really important part of art. But then, we live in the 21st century; art is much more conceptual and I think that, in a sense, those tools then would allow us to engage in much more conceptual issues and leave the kind of crafty bits to a machine to do it on our behalf to a large extent.

But, saying that, I wasn't impressed by anything I've seen produced by AI, and I can say that I'm really impressed by what humans are doing, as well.

Ben O’Shea: And I know, because you guys are so interested— When I used the image generator to create that avatar it actually spat out fifty variations. Ten of them were babies <Oron laughs> that looked vaguely like me and had really weird hands.

But Oron, so, we've seen a couple of high-profile examples of art competitions, whether it's photography or painting, whatever it might be, and an AI entrant has slipped through. Do you think then, by what you're saying, that that's okay if there's like, there's a human prompting it. So, there is some agency by a human artist?

Oron Catts: Yeah. I don't hold art to being sacred, in the sense that it's only kind of driven by human creativity. I have an issue with creativity anyway. I used to teach creativity and I used to realise how problematic even that definition is.

Um, yeah, but you know, you've seen scientific journals are also accepting AI-written papers. You've seen, obviously, a lot of what you read in the media is already being generated. As a journalist, you would know it.

So, I think what we do need to do—and this is something that we're facing not just with AI—is the reduction in the training of critical thinking, and developing those quick, the critical faculties of our existence.

And in a sense, there's something really charming about things because we haven't talked about this kind of ‘deepfake’, which is another kind of output of AI, where you can actually generate, like-images and videos of someone saying things with a voice, with a face, with facial expressions, but that they never said.

So, in a sense, you know, in the near future, we wouldn't trust anything beside direct face to face interactions with others which, again, might not be a bad thing. I think healthy mistrust is something we need to exercise even without AI.

Ben O’Shea: Yeah, I think that's a good point. You guys familiar with the deepfake technology? Have you come across that? It is definitely sort of pointing to a future where our perception of what is real may be not as clear as what we might think.

Now, Ajmal, I interviewed Neil deGrasse Tyson a few weeks ago and we talked about AI and we talked about what that might mean for future industries and who might have to worry about it. And he made the point that, you know, when the car was invented and became popular, Henry Ford was convincing everybody to get rid of their horses, jump in cars.

And no one really spared a thought for the people whose job it was to go around scooping up all the horse poop, but that industry was completely made redundant overnight. Can you think of some industries that will be particularly affected by AI?

Ajmal Mian: Well, experts say that fifty percent of industries will be affected by AI, so, there's a lot. So, if you randomly pick up ten, you know, you could easily see half of them would be affected by AI. So, the construction industries. The software industry. Cars construction. Everything, you know, yeah. I’s everything.

But I'm against this concept that, you know, people are going to lose jobs or AI is going to cost us jobs because all that is going to happen is that the jobs are going to change. They're not going to vanish.

You know, if you think of, or if you look at history, you know, every time a new technology has come, the first fear was that it is harmful and it will cost the loss of jobs. And, you know, nobody stopped from updating that technology because it might be harmful. Like, you know, the 5G networks. And you didn't find, you know, a perpetual loss of jobs for the last hundred [or] two hundred years.

You know, all that we have seen is change of jobs. So, fifty percent of industry is going to be affected.

Ben O’Shea: Wow. We're now starting to, I guess, ask more nuanced questions about how AI works, and a lot of it is some of the generative AI is based on these sort of fast language models. And Ajmal, I'm sure you can explain it in detail, what they are. But Oron, from your perspective, like, how do you, I guess, get your head around the idea that some of these language models might contain biases? Gender, race, social status?

Oron Catts: Yeah. I think it's worse than that. I think a lot of the drive around data at the moment is about maintaining a power structure. So, I was recently in a conference in Munich where one of the panels was about what they refer to as AI-driven enterprises. And the idea there was to basically run companies, corporations, that are already considered to be a legal person, run not by a CEO, not by a board of directors, but by AI software.

And I was scratching my head, why those people— You know, it's one of those conferences, like, it's global where people pay €3500 to go in and actually have to apply to even be in the audience. So, it's a very select group of people.

So, why are those people are discussing the idea of AI-driven enterprises? And I realise, you know, this is a way for them that they figured out they'll be able to maintain their power.

So, the biases are not just about race, which is huge, and not just about gender. It's about how and who's calling the shot, where the bias is leaning towards, and how those biases are then going to serve certain groups in society.

So, I think we, the fact that we are just focusing on the very obvious in identity politics issues, which again are extremely important— We are losing the eyes from the real world. Like, who are calling the shots? Who is feeding the AI with the data? And why are they so protective of the type of power structure that they tend to hope that AI would maintain for them?

Ben O’Shea: Well, the media is one of the industries, one of the fifty percent of industries that is impacted by AI, and we've seen some media outlets using AI text generators to write basic stories like traffic and weather stories.

The West Australian doesn't do that, but we use AI. It helps us curate what stories go behind a paywall based on an algorithm that can predict the behaviours of readers. And initially we didn't trust it and so we, for six months, tested the AI, which is called SoFi, against our human curators.

The AI won convincingly. Like, it was not even remotely close.

And then we went on to finish second in an international award for media innovation. So, it just goes to show it's, so many industries are impacted but not necessarily in a negative way that that some of the doom and gloom naysayers may suggest.

But we talked about language models; Ajmal, can you explain how they work in a way that we can understand?

Ajmal Mian: Well, to understand how they work, we need to understand how they are trained. So, the language models are trained to predict the next token. Tokens are words or collections of words.

So, we have these lots of text available on the web. And we have these big companies. They make a very, very large model. The larger the model is, the more capacity it has to learn and the more kind of context it can contain. So, it gives it a very long phrase and or a very large set of tokens [from] which they collect context, and then the language model is asked to predict the next one.

And when it predicts the next one, that gets fed in as input and it predicts the next one. And this process, so on, and then it outputs a large set of text that, you kind of think that the AI wrote this, you know, but it never planned to write like this. It just spat out token after token. And because it was trained on such a huge amount of data, those tokens connected really well and made this whole paragraph.

And behind that, you know, the language model doesn't actually have a model of the world. So, it doesn't even understand itself, what it is saying.

I know there are very renowned researchers who believe that, you know, they actually— If it didn't understand, how would have how would it have given this kind of an answer and how it could have given you the reasoning that it came up with this answer? Language models can also give you reasoning as to how it reached to this answer.

But again, all of them are just sort of tokens after tokens and, because of their training that this should come after this and this should come after this. I hope I've given you some idea of how these language models work.

Oron Catts: If I may add something both related to that and to your previous question. So, my daughter is in uni at the moment. Second year over there. And her student job is to work for the Parliamentary library, who is going through this huge process of digitisation of the whole of their archives using AI. And her job is to correct the AI mistakes and AI’s inability to distinguish between different types of documents, for example.

So, she can sit in the library with her earphones, listening to a podcast, and go through five hundred documents an hour and do it like that, without even thinking; while the AI, which, I would say— It's the Australian Government, so it wouldn't be the cheapest one on the market. It can't even solve those problems.

So, first of all, as you said, it generates new jobs, and it's a great job for a student. You know, she— But also it can spit out things but the, actually, the taking in, it's not something that it’s doing very well.

Ben O’Shea: It doesn't recognise, it doesn't understand the things that it spits out. And, listening to Ajmal’s explanation of these language models, that— We know, the bigger the better, so they're harvesting vast amounts of information on the Internet. Oron, from your perspective as an artist, does that create an issue of copyright infringement?

We've seen that there's a couple of high-profile cases in America at the moment where comedians and authors— Like, Sarah Silverman is suing Google and OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT, for copyright infringement because they've found traces of their work in responses that have been generated by ChatGPT. Is that something that we need to worry about? Artists should worry about?

Oron Catts: Again, I might be the wrong person to ask this question because I don't believe in the current form of intellectual property regimes. You know, they’re problematic anyway, so whatever is going to bring it into a crisis, go for it. I have no issue.

But the other thing is obviously— You know, you say you asked ChatGPT to give you a Steve Jobs style thing. Maybe there were, like, three sentences there that might have worked according to it but the rest was like Crocodile Dundee. So obviously, again, it doesn't really do the work very well.

But the more the merrier, I think. It's, like, it doesn't really matter. I wouldn't— This idea— So, I suppose, also, to put it in context, the kind of art that I'm doing is not covered by copyright because I'm using biological, living biological systems mostly for my art, and now I'm using, also, some computational systems. But according to the Australian copyright law it's not considered to be art that is copyrighted, so I don't give a shit.

Ben O’Shea: <laughs> You're an artistic anarchist, so I'll put the question to you then, Ajmal. Do some of these companies have an obligation to attribute or acknowledge the sources that they're using to create and profit from, in the terms of their language models?

Ajmal Mian: Well, definitely. And this also brings me to your previous question on creativity. You know, are these models really creative? You know, is this, can we call this creativity? Can we call this creative art?

Well, the model cannot output anything that it is not trained on. You know, for example, you know, I mean, I don't know. I'm a little bit [of a] fan of Picasso's art. You know, how ... Cubism and, you know, making things out of straight lines and triangles and this and that. You know, we actually have an AI library we named after him. It's called Picasso Library, you know, doesn't do anything like Picasso, but just the name.

So, anything that the AI would output would be a combination of what it has seen before. So, it's nothing one hundred percent new, but because the combinations are so many— You know, it was trained on millions of data, and it's combined in such a way that one could sort of vaguely call it— You know, just like you have a camera. You know, you set up these filters and this and this and that, all these combinations, and then the lighting, and you come up with this new picture, and is that art?

You know, so to that extent. And definitely, if they're using data— You know, if Facebook is using people's data that people put up for their friends to sort of read and see, and other social networks or anything else, if people are sort of publishing on their name, you know, they need to have, you know, receive credit for what they have put up.

And, you know, someone should not be allowed to train a model on that and at least make money out of it.

Ben O’Shea: Well, a renowned deep thinker was U2— Ah, was Bono from U2, and he once saying that every artist is a cannibal and every poet is a thief. Oron, is that the sort of thing that you subscribe to when it comes to this idea that we're talking about?

Oron Catts: Yeah, to a large extent, because there's very little originality. You know, even humans do it. They only can use what they have out there as inspiration, as what drives them. I think what's really interesting with human intelligence, that human intelligence is based on a lot of misunderstandings.

You know, this is how evolution works as well, accumulation of mutations, and even in the way we think. So I think the most creative artists are those who are neurodiverse, that they don't really get the world the same way that we are, and their output is very different, which looks original, which looks new, because the way they process it, if you want to use this language, is actually very, very different than the usual thing.

And again, when we talk about intelligence, that's exactly the issue. It's like, we tend to standardise the idea of what intelligence is while the outliers are actually those who are doing the most interesting works, where the breakthroughs are coming through.

So, you know, the issue I have— And as an artist, I'm interested in mindsets rather than datasets. And I think the mindset that drives artificial intelligence and how it's being pushed into society is exactly the mindset that is trying to remove any outliers from the system.

This is how the datasets work as well. It's like, that's how the curve operates. This is where most of the answers would come. You know, the centre of the curve. So, I think what we need to do is actually try and find ways in which AI can actually celebrate the strange, the outlier, the things that are not, kind of, the regular things that we expected to come out.

And this is, I think, where it's going to struggle. And this is where I still believe that humans would be able to overperform in many, many cases.

So yeah, so, creativity and the way we think, it is really about kind of when we get short circuits, when we are not operating in the optimum conditions, that's where the most interesting things are coming out.

Ben O’Shea: And, Ajmal, we talked about, you know, the industries that would be impacted by AI and a lot of the debate around the topic is framed around what we're going to lose. What we're going to— What is going to be taken away from us by AI. The jobs that are not going to exist anymore. The abilities that we're not going to have. The things that we're not going to be doing in the future. What is AI going to give us?

Ajmal Mian: AI is going to upskill us. You know, the time it takes to write, let's say five pages, you know, now or say, let's say one day before ChatGPT, is now reduced by many, many times.

And I'm not talking about just giving a prompt and just copy-pasting everything that ChatGPT or any other language model spits out. It’s just getting ideas from there. I mean, for example, if you ask me, yes, I do use ChatGPT as a writing aid, and a lot of our senior scientists in AI, they do recommend that you must use language models as a training aid, as a writing aid. They're a great writing aid.

So, it's going to upskill us, you know, in a lot of different ways. Rather than doing a literature survey or something— You know, let's say I want to make something, ‘X’. X could be a product or X could be a building project in my backyard writing, you know, so I— In previous days, I used to give a Google search and it would give me documents. I need to go there, read those documents. And now I can just tell that to a large language model and that will skim through all that and get the information that I need out.

But I still have to check which of those are really applicable or not. So, I can just use it. But it did reduce my search time for all those things. So, it's just another, just like any other machine that we have. You know, it makes our work faster but it doesn't allow us to do something like this, you know, like something not with a single click. It just upskills us.

Oron Catts: Yeah, it's funny, because actually I would say it de-skills us. It takes away a lot of our abilities.

Ajmal Mian: Oh, well, from a different point. I know your point is that then we will lose this ability of sort of being able to do things that we were, you know— I mean, take the ability for us to read a paper and analyse it. Now we give the paper to a language model that will read it and give us the gist out of it. So, that risk is there. Just like if you get too much used to calculators, you know, you might not be able to be as good as doing calculations beyond the simple multiplication and addition.

Oron Catts: Yes, or else you'll find, [you’re] not being able to find your way without a Google map. Yeah. But— And this is exactly— Those kind of things are about the point I made before. Because when they’re doing the literature review for you, or kind of all of the data mining for you, it means that they would leave out the odd things—the things that actually might inspire you, the things that actually might give you the edge—because everyone would use very, very similar ways of analysing the vast data and the output would always be the same.

Ajmal Mian: Well, I think that difference will boil down to— You know how you have these, ah, lots of nice products that are made in, ah, factories. You know, products like, [from an] assembly line, right? And then you go to this other shop. Handmade. These are handmade shoes, you know. They have their own— So, that kind of niche would remain.

Someone who actually goes to these documents and finds these things manually, they might have an edge over the remaining, the rest of the population. But the rest of the population—a lot of people, you know—they would do this, these tasks much more faster and would still rank above a certain threshold to sell their products.

Oron Catts: So, yeah, so, I suppose the question, maybe, we should serve it is, is it going to make us dumber or is it going to make us smarter?

Ben O’Shea: It sounds like it’s going to make some people smarter and, maybe, some people dumber, depending on how you use it. Just like, I guess, a lot of technology depends a lot on the human user.

And so, Ajmal, Oron’s daughter, it’s her student job to find mistakes that AI makes. And I think anybody who’s probably used ChatGPT or used an AI image-generating tool will realise that it’s not perfect. Like, it makes mistakes. What level of critical task would you be comfortable allowing an AI to have complete control over?

Ajmal Mian: One hundred percent control? Ah, I mean, at the moment I wouldn’t give one hundred percent control to AI for any critical task. So, if— I would give it tasks, you know, that would reduce the number of people required to do that task.

So, it sort of acts as an intelligent assistant, you know, where the shots are always called by some more intelligent entity and, at the moment, that is a human.

Ben O’Shea: Yeah. Thank God. And so, ah, Oron, what opportunities to do see AI giving us in the future?

Oron Catts: It’s a good question, because I was trained to be critical of every technology and this is kind of what I make a living out of. Not saying that I’m not using technology, because I totally— I’m an early adopter of everything because I want to test it.

But I do think that it is going to make our life easier in many tasks. Like, kind of dumb, menial tasks that we are wasting our time— We are going to see a lot kind of those little, incremental things and, again, I agree with Ajmal, about the fact that it’s— We still have to remember, it’s not intelligent. It’s a dumb assistant that is there to try and support us.

But there are things— So, for example, in biology, there’s the big issue about understanding how proteins fold. And it’s a really complex issue, because you have the same type of amino acids that would form a protein but you wouldn’t understand the way it folds in three dimensions, and it’s a huge task to try and understand and predict the way those proteins are folding. And it seems that AI is able to do it really good.

AI seems to be also really, really good at kind of monitoring things and then alerting you to something if something goes wrong. Yeah. So, again, there’s many tasks like that [where] it might be useful.

But I agree, I don’t think we should allow it to have one hundred percent control over tasks that, really, we rely on. And my concern is that it’s obviously going to be used for many nefarious purposes.

Ben O’Shea: Well, that segues very well into my next topic of conversation. Can I get a show of hands: anybody who’s seen ‘The Terminator’? Yeah, yeah? ‘The Matrix’? So, and a lot of science fiction movies— I write about movies a bit. A lot of science fiction movies depict this dystopian future where the AI has gone rogue. It’s out of our control. The genie’s out of the bottle.

And it invariably ends up with humans on the wrong end of the equation, because the AI is so much smarter. It evolves so much faster. We live in a digitally-based society so those systems are very easily compromised by an artificial intelligence. Is that something that keeps you up at night, Ajmal?

Ajmal Mian: No, it doesn’t. <laughs> I don’t think AI is going to get to that level any time soon. You know, I’ll add this. Any time soon. And that should matter, you know.

You don’t need to worry at this stage that AI will get smart enough, any time soon, that it’s going to start rivalling humans. You know, destroying us or any kind of things like this. No, I think if there’s anybody who’s going to destroy humans, that honour kind of belongs to humans.

Ben O’Shea: Oh, that’s disappointing. What about you, Oron? Can you, like, fan the flames of these conspiracy theories?

Oron Catts: <laughs> Not really. I totally agree. But I think the problem is that humans are going to basically use AI as an excuse to do things and not take responsibility over them. And, you know, human judgement is not that good. We’ve seen it, you know. We’ve seen it in politics all over the world and, some places in particular— You know, those things are scaring me the most.

But the thing that scares me the most is actually, you know, climate change and global warming. And I don’t think that AI would be coming to our rescue any time soon. And that’s going back to the issue of the bias, because the problems AI is being asked to be solved in regard to climate change are very much driven by the set of values of the very same people that feed it.

The tech bros in Silicon Valley are feeding it, you know, to try and solve problems while making profit. And I don’t think that’s the right way to solve the problem. So, I think we are— If there’s something that keeps me awake at night, it’s not the AI.

Ben O’Shea: Well, Ajmal, can you at least satisfy my sort of dystopian sci-fi dreams by telling me— The server farms. You know, the vast amounts of energy these language models use. These are contributing to global warming.

Ajmal Mian: Yes. Actually, that’s one thing that, ah— One thing that is overlooked is AI models, they take up a lot of energy for training. They run on huge machines for months, sometimes years, to get trained.

You know, the training never ends. You know, they start from the last point that they left and they keep training it again, and more and more. Keep coming up with bigger models, larger context, with more neurons.

And it’s actually a very, very big contributor to the greenhouse, ah, the carbon footprint that is there. And in terms of, you know, following up on your comment that global warming is really a big issue; but the AI is contributing to find solutions in that. You know, AI is being used to find, ah, renewable energy, how to store energy, how to get chemical reactions that we need for storing energy more efficient.

I was at a conference in Vancouver a few months ago and one of the keynote speakers was from chemistry. You know, I mean, what is he doing at an AI conference? He was telling us that, "I need your help for solving this problem.” And that problem he explained so well that a report comes back to how, you know, AI is used for 3D shape analysis ... <inaudible> And I said, I thought, you know, I've been working in this problem in the AI domain since 2003 and now there's an application in chemistry. Yeah. So, AI can contribute towards, you know, renewable energy as well.

Ben O’Shea: And I think there was a breakthrough recently where AI was used to test antibiotics and maybe it might pioneer a new antibiotic that can deal with the, you know, sort of the virus-resistant antibiotics that we currently have, the antibiotic-resistant viruses that we're currently seeing.

And so— But as members of the general public, when we see stories about like panels of experts, like people, top people from Google and other Silicon Valley types who sign open letters that say AI could be as serious a threat, an existential threat, as a pandemic or a nuclear war. Do we just discount that or should we take those fears a little seriously?

Ajmal Mian: Well, there are experts who are at the same level who say that this is not true. You know, so I would say there's a fifty-fifty balance over there, and one could do their own analysis.

You know, I will tell you a different perspective of— While this destruction of humanity part is not going to happen anytime soon, there is another aspect of AI that is more dangerous, which is how brittle AI systems are, which is how easy to fool these AI systems are.

For example, you have the smart gate that works on AI. You would only let certain people in and not the other people in. And you can easily fool that, you know, putting on certain glasses or this or that. Or, you know, as a general comment, you can put small errors in the data intentionally that would fool AI. And it's so easy to fool AI.

And the same goes for, even if the— And, I mean, a lot of these people, they buy AI system, you know, like, from suppliers, from third party. And the third party could have put backdoors in these AI systems; backdoors in the sense that every time, you know, you kind of asked DALL-E to make an image, it makes an image of, you know, a certain brand. Like, every time you ask it, you know, 'food’, it makes a McDonald's burger.

We actually have a paper out on that now, you know, putting this kind of, you know, just showing how easy it is to put backdoors in these AI models.

So, you ask it, ‘burger’ and it always, or most of the time, it's a McDonald's burger so that you don't become suspicious and you say ‘coffee’ every time or most of the time, it's Starbucks. And you can actually control how many times you want Starbucks to appear. And if you say something else that you haven't put the backdoor on, it will act normally. And they’re called triggers.

And one of the famous examples was given for a stop sign. You know, a stop sign should be perceived by self-driving cars as a ‘stop’ sign. But this sticker of which I could choose, you know, or with which the, let's say, the malicious party can choose to be, may be a sticker of a minion or a Nike sign or anything.

When that sticker is there, this stop sign should mean a sixty kilometres per hour speed sign. This is how easy it is to fool these AI models.

So, and based on this—and this is just my one evidence that since it is so easy to fool these models nowadays, you know—how could these models sort of become so advanced that they would beat us at our game?

Ben O’Shea: And so, Oron, further to what Ajmal just said, is that how you feel about it as well? That, you know, it's kind of, like, the limiting factor of the AI, and also maybe one of the biggest dangers around them, are the human actors who are involved in their creation and use.

Oron Catts: Exactly. And going back to your previous question, the fact is, the very same people from the industry warning us against the incredible power that we're yielding— It's obviously part of the hype machine. You know, at this stage what they are trying to do is to generate unrealistic expectations in regard to the power of the technology, which also is being served by scaring us in an unrealistic way. Yeah. So, both sides of the coin, of how powerful it is and how dangerous it is, are serving towards this idea of how powerful it is.

And those are the very same people— You know, if OpenAI are the people that are putting the backdoors for McDonald's, are those the people that you can actually trust making the right decision of either self-regulating or even putting forward what they think the dangers are? Well, it's like basically a misdirect into, don't see us actually pocketing so much money out of putting those backdoors for advertisers.

Because that seems to be how the tech industry is operating now. It's about manipulating us, either through complex algorithms.

You know, there's always with the— The Social Network documentary that was trying to show us how dangerous those social networks are, was also basically a promotional video.

Um, but the claim that somehow those algorithms know us better than our mothers. Yeah. By convincing us that this is what they know, we are already being manipulated, regardless if our mothers know us better or not.

So, I'm really concerned. And I spend a lot of time with Silicon Valley type people, especially in the field that I am, which is around the idea of food systems. And that's another thing that AI is now moving really strongly towards. And it's the very same mindset.

So, you know, I have no issue when someone like Mark Zuckerberg is playing with my social life. But when you start to play with my food, when they start to play with my health, when they start to play with other critical systems, I just said this is where I'm getting really concerned.

So, it's about regulating the people. Not so much of technology.

Ben O’Shea: Let's talk about trust and regulation. So, Ajmal, as someone who works in this field—and I'm sure, as a researcher, you want to be at the sort of the bleeding edge of what is possible—is there enough done by governments to ensure that there are the checks and balances in the world of artificial intelligence?

Ajmal Mian: I think there's not enough done in that domain. The speed at which AI is advancing, you know, the government agencies and the policymakers are always a few steps behind. And maybe more than that. You know, we're behind in catching up.

You know, there are these models that are put up that will generate any type of fake image, will make anybody say anything else. And there is no regulation as to who can generate these things and who can actually put them [out].

And people might be saying, well, look, this can do this. You know, but what about the malicious use of that? You know, what about some sort of watermarking, you know?

Putting in these that differentiate the real from fake is just, like, you know— Oh, look, we have found a new way of making this fake currency. Look, I can put it in this printer and print it out. You know, that's a crime. You know, that's— The same should be for any other malicious use of this AI technology or any technology that comes up.

The government or the policymakers should quickly catch up on that and sort of lay down rules or lay down some rules that are very general about, you know, how a technology can be, you know, harmful and, you know, sort of keep the law enforcer in pace with everybody else.

Ben O’Shea: And, Oron, I'll ask the same question to you because, in your art, you're also pushing boundaries and pioneering new art forms and going places where artists haven't gone before. That's part of human nature. It's always been the way of our evolution, whether it's a scientist or an artist pushing the boundaries, seeing what is possible, more so than wondering whether it should be possible or what the consequences might be if we make it possible. How much, how much can we stop that? Like, is that something the government can regulate, do you think?

Oron Catts: Yeah. So, so it's an extremely— And this is something I'm grappling with for years now because a lot of my work was, set up what I thought to be cautionary tales.

So as an artist, I started to basically liberate knowledge from the confines of, in my case, it was mainly the biomedical world, and then put it within an art context as a way of setting up scenarios for us to contemplate how it's going to change the ideas that we have and the mindsets that we have in regard to life itself.

And that ended up becoming inspiration to a new industry. So, actually, in 2010 I was in a conference in New York where my work was used as, in the timeline of this new industry of growing meat without animals or growing leather, as the trigger that started this whole new industry. And obviously I haven't seen a cent out of it and I'm not complaining but— So, I'm grappling with it.

But I'm a staunch believer in the precautionary principle. So, I believe that we as a society have to be cautious about it. This acceleration towards those empty promises of betterness[sic] which comes out of places like Silicon Valley, I think, are extremely dangerous.

Those, there's a really beautiful reference to Ancient Greece, that they didn't like the idea of hope very much because they found that hope is obscuring our ability to have a realistic foresight of what's coming.

So, that's why I say that I'm a pessimist. So, I think I’d rather engage in realistic foresights than in imaginary hope, which is maybe not something you would associate with an artist.

But I do believe that, yeah, as a society we have to put, to basically engage in the development of new knowledge because I think this is part of human nature, as I said, and also because it's important for us to understand the world we live in.

But the application of this knowledge has to be driven by the precautionary principle. Basically, we don't have to deploy it. It's not going to make any difference if we wait five years or ten years, you know. It's actually going to make a huge difference in the sense of us being able to realistically assess where we're going.

You know, the Silicon Valley ethos of ‘fake it till you make it’— Again, it was okay when it was dealing with kind of selling of products through advertising, but the ‘fake it till you make it’ and the Elizabeth Holmes case where—I don't know how many of you know the story—was a great example, where this very logic then moved to health care. And some people got wrong diagnostics because she was interested in faking her idea until she thought she would one day make it. Now she’s in jail. Yeah. <laughs>

Ben O’Shea: So, what I think about— When I think about AI, I think about like a scientific field, like cloning, which is something that's happening around the world to various degrees. And you just get the feeling that maybe it's happening in some places, in some jurisdictions where there aren't a lot of regulatory controls and then, you know— What might be unleashed?

Ajmal, do you think, like, AI is a bit like that, that there might be jurisdictions around the world where they just go a little bit too far? Is that even possible?

Ajmal Mian: I think they haven't gone that far, but definitely they have given common man a lot of capability in terms of how they can do sort of harm to the society. There are language models that would help you write a virus or a sort of, you know— There's one GPT, you know, it's just made for, on the dark web, for malicious purposes. So, it definitely needs some regulation around it.

And it’s in human nature to discover new and newer things. So, we can't really stop that.

You know, I mean, that letter by, a few months ago, that we should stop AI research for six months, it absolutely made no sense. You know, this is not possible.

This is not in human nature to stop discovering, you know. We will keep discovering. All we need to do is to regulate the findings and, you know, ensure they're only used for good and not for bad purposes.

Ben O’Shea: I'm going to throw it over to you guys to ask some questions soon, so maybe just have a bit of a think. And I'll just put one more question to my experts today. So, Oron, I'll start with you. Like, to what extent do you think the future, when it comes AI, is even knowable?

Oron Catts: I think it's really hard to, you know— There's so many variables and, you know, I just started to tell you story about the birth of industrial biotechnology, which, if I may indulge in that for a second— Apparently, the birth of industrial biotechnology is going all the way back to the First World War, where the [British] and the Allies, where they were fighting Germans, didn't had enough supplies of acetone for the generation of explosives.

And then this Polish migrant in the University of Manchester, a chemistry doctor, was able to figure out a way to culture bacteria that produced acetone and basically ferment it. And there's some theory that says that this tilted the whole war, that basically now the Allies were able to generate a lot of very cheap explosives, and that really gave them the upper hand in winning the war.

And that migrant was, also happened to be the Jewish, the head of the Zionist movement. And as a ‘thank you’ letter, he got a letter from the Foreign Minister of the UK at the time, Lord Balfour, where Palestine was given to the Jewish people as a thank you for his war efforts and for the invention of industrial biotechnology.

So, we're still dealing with that, the outcomes of that. Yeah. So, this idea that we can somehow predict and have a linear prediction of the direct impact of those types of innovations on the future is impossible to predict, because there's so many ripples that are coming out of it.

So, there might be something that looks very, very small and insignificant in the future of AI that would actually have a much larger effect on human society and human culture towards the future that we won't be able to identify. And that's, again, the idea of the outlier that you referred to before.

Ben O’Shea: Let me phrase it this way to you, Ajmal. How far do you have to look into the future before you get to a point where you no longer feel confident in what that future looks like?

Ajmal Mian: Well, my opinion on predicting future is the same as Oron. Basically, what happens is that there is a breakthrough. You see this surge in invention and people kind of only extrapolate that single side and say, okay, in twenty years you'll have self-driving cars or something like that.

They think they can work out the way, you know, with this linear interpolation of, you know, that we're going to achieve this by this design. I'm sure there are a lot of statements now that in twenty years, yeah, AI's going to do this.

It’s going to do this because of the recent surge, you know. So, we really don't know what's going to happen in in the future.

Ben O’Shea: Someone put it to me this way recently. So, you remember Back to the Future, maybe it was ‘Back to the Future 2’ where they go to the future and Marty McFly goes to his future relative's house.

And back then, when the film was made in the sort of the mid ‘80s, that was what they imagined life would look like in 2015.

And it was a house that had fax machines in every room, which clearly is not how things turned out. But it just proves your point, that it's very hard to look forward.

Things that we think will be a linear path to the future won't exist. Things that we don't even expect to become anything will become supremely important in the future.

And now, I'd love to hear some questions from you. Just throw up your hands and we've got a microphone for you. Who wants to kick it off? Yes. Gentleman in the front row.

Audience member 1: Um, on the point of AI models being too dumb to build a model of the world because their task is to predict the next token: you could argue that a human being evolved from a common ancestor with the goal of reproduction and happened to build a model of the world as a contingent goal that made it more effective at reproducing.

Why doesn't the same argument apply? Like, why isn't it possible in principle for a large language model to build a model of the world because it happens to make them superior at predicting the next token?

Ajmal Mian: Well, they can make a model of the world, and they're kind of also relying on other external models to give them that information. But, at the moment, the way that they're currently trained, they don't have a sort of ideal model of the world.

You know, they don't really understand what they're saying. They're just purely trained on text.

And some theoretical sort of researchers, you know, like theoretical physicists, they might say that, well, a lot of their work is based on reading previous stuff and then trying to come up with theories, so why can't language models work in that?

And the argument against that is that, you know, even subconsciously we still have some model in us and the way we think is not because of sort of, you know, digesting these words and coming up with next words.

We actually, in our mind, we think based on some sort of a model and in a structured way. So, I'm not saying that the language models cannot do it, but this is not how they're currently doing it.

Oron Catts: So, just to be clear, you know, obviously there's a reference to this idea that human consciousness is actually an emergent behaviour of our complexity. When that threshold would be reached, you think? How complex the system have to be so that emergence would occur?

Ajmal Mian: I think it would be a combination of many models, you know, interacting with each other, communicating with each other, and when exactly it will sort of be equal to the level of a ten-year-old or to the intelligence of a dog, that that's hard to say. You know, but the way that they will actually become more intelligent is by communicating with each other.

And it's sort of happening at some level now, that the language models are interacting with the tools that are designed for mathematical calculation because the language model in itself, purely itself, is horrible at maths.

But it can detect very easily that, oh, this question is a maths a question. Let me book that tool or that model or that guess. That's not even a neural model, that's a simple calculator and just does a calculation for it and returns the answer.

And the same goes for some more complex mathematics. Or if it's a sort of an engineering question, you know. It can detect that this is an engineering question, it's sort of ... It's sort of like, contact back when— I don't know anybody using a paid version of ChatGPT, the one ... you know, you can have those, lots of plugins. So that's the example, you know.

Oron Catts: So, how important is embodiment if you suddenly have the system embodied in the world? Let's say, a self-driving tractor that has instructions and is really, really smart. Can't speak very well, but it's really, really smart and it's really aware of what its task is in a world. Aware of its surroundings. You think maybe an emergence—?

Ajmal Mian: For specific, well-defined tasks, AI will become much more better than humans because humans are kind of slack. You know, you can even kind of doze off.

You know, you tell an AI model, the camera always looks front. You know, maybe you would fix the camera. They would look front. You tell a human, look where you're driving. The human is not going to always look where they're driving, you know.

So, these kind of tasks, the AI or machines are definitely going to be good at.

And in terms of self-driving, the first thing that's ever going to get automated is the cargo trucks, because they have a very, very defined goal from this point to this point. Nobody gets off, nobody gets on. You know, nothing else happens in between. Just avoid obstacles. You're unsure, stop until the road is cleared, and go on.

Oron Catts: So, can it get depressed after a while?

<audience laughter>

Like the [doors] from the Hitchhiker [Guide to the Galaxy]—

Ajmal Mian: No, I don't— I mean, this— I don't think that the machines are ever going to get sentient or going get depressed or— I think that is the advantage. I mean, you have humans for that.

<audience laughter>

I mean, it's hard enough to, you know— <laughs> There's these complex relationships, you know. You all know what I mean? You know, all levels of, you know, battling up and down and, you know, these relationships. Machines are going to stay out of that.

Ben O’Shea: All right. While we get the microphone to the next person, it sounds like the language models will get smarter by speaking to each other. So, we've got a bit of time because they're only speaking to us at the moment.

Ajmal Mian: Oh, no, I didn't say that language models get smarter by speaking to each other because they would still be spitting out all the data that they are trained. You know, if one language model is trained on this set of text data and the other one is trained on that set of text data, exclusive, then they can learn from each other.

If they're trained on the same set of text, they're not going to learn anything new from each other.

But they can do more tasks by approaching models that do other, you know, sort of more specialised tasks. Like, you don't have to— A language model is an excellent interface between everything else and human because language is where we sort of want to communicate.

I mean, other than pressing buttons, you know, you’d would say, you know, hey LLM—large language model—can you do this? And then it’d say, I can do that, you know. And approach one thing to do one part of the task, and another to do another part of the task, a third thing to do a third part of the task.

Audience member 2: Do you think AI would be as effective or as financially beneficial if we monetised the corpus appropriately? As in, I train a self-driving car algorithm every time I pay for something online. And then the Sarah Silverman case in the US about the DALL-E work that's using some of her outputs and IP. Would that actually make it more cost effective to the owners of the corpus?

Ajmal Mian: You mean that every time we are online, they ask us to identify stop signs and cars in these images? This kind of work?

I think a lot of these websites and a lot of these tutorials say, “You know how these models are trained? When your captures ask you to identify cars and sidewalks. They're always sidewalks and cars and these letterboxes.” I don't think they're trained like that.

A major breakthrough happened with self-supervised learning, and self-supervised learning is that they don't need to know where there is a car or a letter box or anything. All they do is that they automatically hide a part of the image and then learn to predict that part of the image.

So, that's where the bulk of the learning is done.

... is a very important part of AI learning now these days, auto completion. So, give it data with missing parts. This data could be an image with a missing patch. This data could be a text with a missing patch. Perhaps the end of the text is missing.

And then at the end, because you remove that data yourself or the AI removed the data itself, it can put the whole data at the end and now learn to predict it.

This is where the learning happens. As simple as it sounds, it's really, really powerful because now you can use everything that is online, everything.

Every image that is online. Nobody has to tag the cars in that image. And once it is trained, you know, all it has learned is to complete that. But in that learning process, it has learned the structures.

Like, so, because there is a road here and here, maybe inside this, there should be a car. So, it has learned that those surroundings. Or, because I see some leaves over here, some more here, and these are parkland. This could be a stem of a tree.

So, it's learning those, the ones that are actually inside the data to predict what is missing from the data. Bulk of the learning happens there. And at the end, when you want to use this model for a specific task, that's when you use those. Okay, this is a car, this is a letter box. And for those, there are very nice data sets that are available, like ImageNet.

Audience member 3: Good night. Is there any formal organisation that is in charge to regulate nowadays this artificial intelligence?

I mean, like the WHO is in charge to regulate the health around the world. I mean, because it looks like that artificial intelligence tries to give us a narrative or one standardisation of the narrative of what's happening in the world.

It’s kind of telling us the history and the world, but who is in charge to regulate this?

Ajmal Mian: Excellent question. You know, I mean, Oron, I don't know of any organisation that is there, and I agree that there should be an organisation. You know, I even have a name for it. WAI.

Oron Catts: As far as I know, there's none. But that's kind of also an interesting thing. So, in the history of genetic engineering in the 1970s, the scientists that were involved with genetic engineering had a conference called Asilomar conference, where they declared an, their own self moratorium over some aspects of genetic engineering because they knew that it can be dangerous.

I really can't see it happening in 2023 because of the fact that most of the research comes out of AI, that is kind of really being deployed, it's not coming from academic universities—that's also a very different now than what they were in the ‘70s—but coming from companies that have a very different sets of values that are driving them. Literally value. <laughs>

Audience member 4: Thank you. Two questions. You talk about the data sets. I'm wondering— I think ChatGPT stopped at 2021 in the data set that it has that it works off. What is the data available to ChatGPT or these large language models?

I'm a lawyer and I use some tools for looking at case law and things like that, and the splash screen that's come up whenever I access it over the last few months is, don't download this data and stick it on a large language model.

So, I assume they're going to try and do something with it at some point. But I'm just wondering what sort of data is actually available to ChatGPT to work on these models.

Ajmal Mian: I think it's the free version, GPT 3.5 that is up till 2021. The other one goes beyond that as well. And everything that you can Google is available to the large language models to learn from, which includes Wikipedia, which includes all these online documents.

And I assume that these models would also—ah, these companies would also have access to libraries. You know, they would have subscriptions. It's nothing for these big companies to sort of buy subscriptions to.

And also, these legal books. Everything that is available on the Internet, paid or free, that is available to a large language model for training. And none of these companies is going to admit, you know, what the exact data is that they used.

So that's where the problem of, you know— And nothing can stop these models from, you know, spitting out sort of a bunch of sentences that are taken exactly from somewhere and, you know, sort of infringe copyright.

Audience member 4: Um. Two more. Sorry. <laughs> We talked about the outputs being from the middle and not from the outside. And there was some talk about sort of taking or getting answers from the middle of the curve.

I’m a bit cheap. I've used only the free version of ChatGPT and I've seen that you can ask the same question twice, exactly the same, and it comes out with different outputs. You know, a couple of minutes later. I don't know how that happens.

What's, ah— My last question is this. I have heard that as part of this regulatory model that we come up with to deal with, you know, the dangers of AI, what we’ll do is we’ll just bomb a data centre. Is that possible?

Ajmal Mian: So, the question was, the middle of the curve, what does that mean? That was one part. So, you'd say that, you know, a lot of things in nature follow the normal distribution. So, we have a lot of things that are mean centred, and less on the, this side and less, you know— So, you have some text that is very deep technical or very hifi English and very less that is actually someone put up as incorrect English.

So, a lot of them would be, you know, sort of in the centre. So, that's why we pick up, most likely to pick up examples from the centre. So, if you're using these large language models and if you're a good writer, you're going to get closer to the average writer.

If you're using these large language models and you're not such a good writer of English, because it's not in your native language, then you're certainly going to get closer to the average of—

And the second part of the question I didn't really get.

Oron Catts: Blowing up data centres.

<audience laugher>

Ben O’Shea: Yeah, bombing the data centres, bombing the server farms.

Oron Catts: I think it is distributed now. It's like, you can't— There's no one data centre where— there's no one.

Ajmal Mian: Even a single data is also distributed. You know, like, say, they have backups, you know, so they know that if one building gets burned up, there will be a backup somewhere.

And I think more than two backups, you could expect. Yeah.

Oron Catts: Maybe a massive solar storm.

Ben O’Shea: There’s a gentleman there with a question. And while we're just waiting, so— Will the AI ever get an awareness of itself? Like, feel self-preservation as an imperative?

Ajmal Mian: I don't think so, but that's my personal opinion. I can't prove it, or no one can prove it the other way around, in my opinion. But I think it's never going to get self-awareness.

I can give one argument in that favour that, while the neural network’s basic neuron is designed on a biological neuron, but the way the neural network gets trained, the way artificial intelligence learns is completely different from how biological species learn.

Oron Catts: And it's also a very abstract model of what a neuron is. Neurons are so much more complex.

Ajmal Mian: Yes, and this is a very overly simplified model of neuron that would just simply do multiplication, followed by addition, followed by a simple function, as simple as just drop the negative values. You know, just make them zero.

So, these three operations and then you do them in lots of connections, billions of connections. You know, neurons, connected to neurons connected to neurons connected to neurons.

And these, they will have billions of parameters. And how, what parameters? What should you multiply an input with and what should you add to it? That's what is the learning process. How do you get data to train it? Well, any data that is available to just do auto-completion to get trained.

Audience member 5: Good evening. I'm just following on the other question we had in relation to the data model sets. Do you think they all really trust based on publicly available information and data in obviously all of the World Wide Web and Google and search engines?

What do you anticipate that's actually going through? The privately stored data that every one of us is constantly contributing on a daily basis. Either by emails, via social media or via logging where you are going, tracking, ectetera. All of those aspects? Is that included in those datasets or was it not admitted publicly, obviously because it's a privacy issue?

Ajmal Mian: Yes, that's included. So, I'll give you a very interesting example. So, I was doing facial recognition research for years, right. Ten years, fifteen years. And then this one paper from Facebook comes out.

Facebook. On facial recognition. They used all of your images to train their model on and boom, you know, I said, okay, that's fine, you know, none of us can beat that.

Of course they use their data, the data that you freely provide online. You know, they use that data to train their models and sometimes the different companies can scrape other ones’ data as well. Twitter had been notorious for that.

You know, anybody could sort of scrape through the data that is there on Twitter and learn from that. You know, models and so on.

So, they use, these companies use all of their own data, but also, any ways that they can access because fake accounts, bots and so on.

Ben O’Shea: There is more awareness around privacy now and most of us who use iPhones will be familiar that you get a new app and iPhone will prompt you: do you want this app to track your data, opt in or opt out? Do we need to be aware of that information from apps, whether it's a ChatGPT, winding up in these large language models.

Ajmal Mian: I think those prompts—you know, “do you want to share your data with this app or not, or this kind of data”—they are a very small part of it.

You download a very simple game, you know, and the list of terms that you agree to, you never read that. And just because you want to play that simple game, you say agree.

You never know. In those terms and conditions, you know, there might be a condition, they’ll have access to your contacts. Why does a game need access to your contacts?

So, I think we are kind of trapped in this, you know, this whole thing that we are sort of— It’s impossible these days, or extremely difficult, to maintain our privacy.

Roaming around, Google Maps is tracking you, even if the app is off. How does Google Maps know there’s a, you know, sort of rush on this road or this, this and that? You know, everybody is not using Google Maps, but Google Maps knows.

Ben O’Shea: We give up our— Oh, there’s a question down here. Got the microphone? Yep. Go for it.

Audience member 6: One thing that I've observed is, human nature is, we're quite able to be manipulated. And I think half of the AI strategy is to teach us to behave in a particular way. Like your comment at the beginning about algorithms which determine buying patterns for marketing and putting advertising into magazines, and how AI was capable of doing it much better than we were, or your other team was.

And I think our ability to become comfortable with an AI generated world where we are told what we should be looking at, how we should behave. I think there's a huge risk in that.

And also, if we have got people out of control who determine what the AI should be teaching us or controlling us in a particular way, I think that's where a lot of risk is.

And I think a lot of the concern I have is about, we are losing control of our lives in so many different ways.

And it's interesting that BlackRock, for example, has got an Aladdin AI which controls the financial systems around the world, and that's becoming very, very controlled in a way that we have no control.

And I think that's where the risk is. I don't know what your thoughts are.

Ajmal Mian: I agree to some extent. You know, AI is kind of driving a lot of things that we do and it's going to take over more and more. And we’ve been repeatedly kind of, you know, sort of in a way that we don't even realise, we've been told what we should do, you know.

And I don't like these type of things popping up on my screen which— You know, sometimes some of these would explicitly tell you what to do. You know, maybe you should do this, or read this, or go or do this or, you know— They keep coming up with, you know, like the screen time app. You’re too much trapped into your mobile phone.

I think the way to avoid this is to get educated because there's no escape. Technology will come.

And when technology comes, there is no stopping because this is in human nature; curiosity, taking up new kind of techniques, advancing in every dimension. That is in human nature.

But the side effects come with every technology and we need to get educated. Maybe Oron will have a sort of a different perspective on that.

Oron Catts: Yeah, because it's a really interesting. It's something I've been grappling for many, many years because working with living biological systems and looking at the attempts of scientists and engineers and companies now to take control of living systems to the nth degree, from genetic engineering to any type of trying to control living processes with the attempt of making them work for us.

At the very same time that we are now developing technologies which are human-made from the bottom up that we’re aware that are so complex that we can't have any control over them.

So, I'm much more interested in kind of the philosophical question of why we as humans are willing to relinquish control over the systems that we created while having this obsession of trying to take control over systems that existed really well without us.