In Conversation: “The door” and queer sexuality in public space

Join a panel of experts and community as they investigate the nature of queer bodies, and queer sexuality, in public space.

There was widespread speculation in 2018 when the Western Australian Museum made a nerve-hitting acquisition – a Gosnells train station toilet door with a hole cut into it that was used by gay men in the Perth beat scene for sex, at a time when homosexuality in WA was illegal. A "glory hole", donated by community champion The Blessed Mother Gretta Amylleta of the Holy Vapours of the Perth Order of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence.

The acquisition gained a significant amount of media attention, being deemed “too tacky to display” by some. Despite public intrigue, by the time the Museum acquired the item at the end of 2018, curatorial content for the reopening of Boola Bardip had already been decided. The door was assigned to the Museum’s vast archives and has since become lore.

Logistics aside, what are the remaining social and political barriers keeping such articles, that can’t be separated from their inherent sexuality, out of permanent public displays?

The panel considered the extent to which queer identity has been desexualised to be made palatable in the dominant culture, and what work needs to be done to recalibrate public collections so that they equitably represent the breadth of the LGBTQIA+ spectrum.

About In Conversation

A safe house for difficult discussions. In Conversation presents passionate and thought-provoking public dialogues that tackle big issues and difficult questions featuring diverse perspectives and experiences. Panelists invited to speak at In Conversation represent their own unique thoughts, opinions and experiences.

Held monthly at the WA Museum Boola Bardip, in 2023 In Conversation will take different forms such as facilitated panel discussions, deep dive Q&As, performance lectures, screenings and more, covering a broad range of topics and ideas. For these monthly events, the Museum collaborates with a dynamic variety of presenting partners, co-curators and speakers, with additional special events featuring throughout the year. Join us as we explore big concepts of challenging and contended natures, led by some of WA’s most brilliant minds.

Listen to previous conversations now.

-

Episode transcript

Lauren Butterly: Kaya, wanju, wanju. Hello, welcome, welcome. I'd first like to acknowledge that tonight we meet on Whadjuk Nyoongar boodja, and pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging. And in that, I'd like to particularly acknowledge First Nations LGBTIQ community members who are such an important part of our diverse rainbow community. I'm Dr Lauren Butterly, and I'll be your facilitator for tonight's discussion, “The door” and queer sexuality in a public space. There was widespread speculation in 2018 when the Western Australian Museum made an acquisition: a Gosnells train station toilet door with a glory hole—as we can see here—cut into it, that was used by gay men in Perth's beat scene for sex at a time when homosexuality was illegal in Western Australia.

The acquisition gained a significant amount of media attention, you might remember, not only in Perth but around the world. Articles all over the world, that we're going to talk through a bit more tonight. Despite this public intrigue, by the time the Museum acquired the door, the Museum had already had its curatorial content ready for re-opening of Boola Bardip. It had already been decided. The door was assigned to the vast archives of the Museum.

And tonight, the panel is going to discuss: what are the remaining social and political barriers keeping such articles out of permanent public displays? Now, we've got a fantastic panel with us tonight with an incredible mix of perspectives and experiences based on lived experiences, on queer activism, on LGBTIQ research, and also museum curation.

Just before I introduce our fabulous panel, I thought I'd share a few reactions that I got when I told people that I was facilitating this event tonight. The first response that I got from a few people was, “What's a glory hole?” [audience laughter] And, you know, that's a very fair question because it's kind of a part our hidden history. It's something that not everyone knows about. And I know that, in particular, Graham and Braden are all keen to talk about these hidden histories tonight.

Now, even— Not everyone in the LGBTIQ community might know what a glory hole is. I should add that one of the people that I explained glory holes to was my mother. And you know what? We both survived the experience. [audience laughter] And, in fact, it led to a really interesting conversation about gay history that my mum hadn't really thought about before. So that's one theme today. Our hidden histories and opening them to new audiences.

The next response that I got was, You're not going to put that on your CV, are you, that you facilitated this event? You know, it's, you know... And you know what? That mainly came from people in our queer community. And I really had to sit back and think about that. You know, there was this sense of, kind of, unease, a sense of, you know, maybe discomfort or concern about the fact that I was kind of bringing up parts of our history when we were criminalised and how that made them feel. And I think that's another theme tonight, that, you know, this isn't just a discussion or a conversation about, you know, what a heterosexual perspective on the glory hole and the door might be in terms of how history is represented. It's also about our own queer community and how we police ourselves in terms of how our histories are represented. So, I think that's another thing to note.

Now, I will say that the response that I most often got was how excited people were about this conversation and how important they felt that this conversation was. That was by far the most common response that I got when I said that I was facilitating this. We have an incredibly diverse audience here, and for some people here, the door will be part of the lived experience, of a time when our community was marginalised. And so other members of this audience, they've come because they want to know more about the history. And I hope that also gives a sense of the tenor of tonight. This is a really important conversation, and we need to give it the proper conversation that it deserves because it is about our community’s marginalisation. But we're also going to have some fun because, you know, our gay community, our queer community, we always find humour even in the face of challenging historical circumstances.

So, we're going to have a conversation now and a panel until about 8.15, and then we're going to throw it open to audience questions, so, I can't wait to hear what your questions are. And with that, I will introduce our panel.

Now, first, I'm going to introduce The Blessed Mother Gretta Amylleta of the Holy Vapors, of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence. Now, the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence is a charity protest and street performance organisation that uses religious imagery to call attention to sexual intolerance and satirises issues of gender and morality. Now, Mother Gretta’s alter ego is Neil Buckley, who is the original owner and donator of the door. He's a long-time community champion in WA and beyond, having served as a board member of PRIDE and WAAC, and he currently sits on the Committee of Residents and Tenants (CORT) for Foundation Housing. He was involved in ACT UP at the beginning of the AIDS pandemic, and he has been an active role in reducing the stigma around HIV that is still present in our community. He has been a prominent advocate for expungement of gay historical convictions and successfully petitioned the WA Parliament for relevant law reform. And I'm really excited that we have the owner of the door here with us tonight, and you'll love hearing the story of how the door came to be at the Museum.

Next to me, on my left, I've got Jo Darbyshire, who's a West Australian artist and social history curator. Now, in 2003, just after the WA Government passed the Acts Amendment: Gay and Lesbian Law Reform Act—we’re gonna hear a bit more about that tonight—Jo worked as an artist in residence at the WA Museum to create one of the first exhibitions to queer a museum—so, The Gay Museum: The history of lesbian and gay presence in WA. By researching and including local community stories and something from every department of the Museum, using strategies from visual arts and, above all, humour, the exhibition questioned the prevailing heteronormative paradigm in museums’ collections, and the assumption that everything was straight until proven otherwise. And that's definitely another theme that we'll talk about tonight, and certainly Jo's curating experience is something we're going to really draw upon in discussing how the door fits.

We've got also Professor Braden Hill. Braden is a Noongar Wardandi man from the southwest of WA and is Deputy Vice Chancellor Students, Equity and Indigenous at [Edith Cowan University.] He's also proudly part of Perth's LGBTIQ community. Professor Hill’s research interests include Indigenous education, identity politics, queer identities in education, and transformative learning. He's also the chief investigator on the first national project exploring the lived experiences of Indigenous LGBTIQ people to better inform community health organisations in working with queer identifying Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, which is such an important project. Braden’s research into queer life in public spaces is going to be another frame for some of our discussions tonight.

And finally, Graham Grundy. Graham is a representative of the Gay and Lesbian Archives of WA, having recently assisted in cataloguing the archives over the past year and recently joined the newly created committee. Graham was involved in regional museums and heritage since 1995, and, along with his late partner, John Rowland, Graham was awarded the WA Civic Design Award for Heritage Conservation in 1995. He's [been] an active member of Pride WA for many years and in 2021-22, Graham also created their archives with records dating back to 1993. Recently, he was the regional museum rep at the WA Museum Consultative Committee for the development of Collections WA. And Graham’s got a real interest in how queer representations at the WA Museum then go on to affect regional representations, which is another really important topic for tonight.

And with that, starting with Sister Gretta...

Mother Gretta/Neil Buckley: Mother.

Lauren Butterly: Mother Gretta! Oh, my apologies. You know, I did joke before— I am Jewish. I didn't quite know how to address a nun today. [audience laughter] I had to ask. I had to ask. Mother Gretta, you rescued the door from the demolition one night under the cover of darkness. Can you tell us what happened?

Mother Gretta/Neil Buckley: Yes. Well, we heard that the Gosnells beat was going to close. So, this door had been there for years, and I sort of knew it had some social value. So, a friend of mine, Bill Martin, had a truck, a flat top truck, so we decided one night to go down and get it. And I don't know if any of youse remember the Gosnell beats, but it's right next door to a police station. [audience laughter]

So yeah. So, we go down one night and some people were using it, [laughs] which is very inconvenient, you know. [audience laughter] So, we sort of waited for them to finish and we took it down. This door weighs a ton. It's a beautiful door, actually. It's made out of solid jarrah, but it weighs a ton. And originally when I got it, I was going to hang it on my wall, but it's just too heavy to hang on a wall [laughs]. So, it did end up being a table in my unit and my playroom. Yeah. [laughs] So, I kept the door for, I think 15 years. And then when I realised all the beats had closed, I really started realising that this might actually have some social value. And that's when I donated it to the Museum. But I was hoping the Museum wouldn't put it back into the closet. But they, you know... So hopefully, if they're not going to show it, they could release it to perhaps MONA or the Sydney Powerhouse Museum, but that would be a great shame to have it go out of WA. So, I am hoping that this will sort of promote them, jolt them, into actually doing something.

Lauren Butterly: Now, when you first came to preserve the door, initially you were really thinking about preserving it for part of your own history. When did you decide that you wanted to donate it to the Museum?

Mother Gretta/Neil Buckley: Well, it was like I said, a lot of beats around Perth ware being closed down. They've got those little self-cleaning units now, [laughs] which is very inconvenient. And that's when I sort of realised that this actually might have some value because, I mean– I suppose there are some glory holes around, but I don't know what they are. If anybody does, could they come and tell me later? [audience laughter] Yeah. So. so it was when all the beats— You know, with, now that we have [apps] Grindr and Scruff and all that, they're the new beats. So, it was then I realised that this might have some social history. And also, I am getting older and I know my family would just bin it if something happened to me, so I just wanted to pass it on to somebody.

Lauren Butterly: And when you donated to the Museum, were you surprised by the public reaction to it or not?

Mother Gretta/Neil Buckley: Not really. I knew there'd be a reaction. I didn't realise it would be such an international reaction because the story was written by— The original story was written by David Bell of The Voice newspaper and, um, the actual story went right around the world. So, it was really good publicity for the Museum. But yeah, I was expecting some sort of throwback, you know, about it. [laughs] I was also hoping it was going to be, too.

Lauren Butterly: And this kind of idea—moving on to Braden—of the history of beats and how this kind of came into that, and whether beats are still a thing that we think about in the current era or, you know, how they were viewed upon in the past, that, that queer in public. How does that fit with your research?

Braden Hill: Yes. So, look, it's not a question I ask in my research often, but I think there's certainly a generational difference in behaviours around sexuality, particularly in public. So, I think, you know, the point around the apps, social ways, social apps and ways in which people interact really does diminish it. But I think what was really interesting in some of the qualitative stuff that we found when we were talking to Aboriginal queer community here in WA was that there was a sense that during COVID, things changed a little bit. There was— And there's a lot of research and literature that talks about how glory holes really came back into fashion globally, because there was a sense that it was safer. It was a safer way of kind of having sex in public because it was a clear barrier. Right. So, it's been really interesting, that. The ebbs and flows. But there's certainly a diminishing of it. And I think the fact that we have it in the collection is really important because I do think it's still going to be a diminishing thing. But public spaces are still important for people's sexuality and exploration of that sexuality. So yeah, it's certainly what we see in the literature as well.

Lauren Butterly: I never would have thought that COVID would come into this as a kind of like— [audience laughter]

Braden Hill: I tried not to mention it. I tried not to mention it.

Lauren Butterly: We’ve had a bit of a resurgence!

Mother Gretta/Neil Buckley: But how is it safer? Cos aren’t you sucking on their dick? That’s sort of the whole purpose of a glory hole.

Braden Hill: It was certainly the perception of safety, right? So, the idea you don't have to breathe on somebody else while, you know, getting hot and heavy— [laughing] There's something that's in between, so there was this perception that it might be safer. And so, yeah, the literature really talked to— The study talked to that idea and I think we were talking about it before—

Graham Grundy: Yeah, well, as a matter of fact, I surveyed my friends and one of the comments was they read online that, in Canada they’d actually recommended gay sex be done through a glory hole during COVID. Yeah.

Lauren Butterly: So, there's probably, I mean, elements of kind of another type of illegality to that, isn't there? Because there were times in COVID where we were restricted. Thankfully not too much in WA, but in other places where they would have been restricted from movement. And if it was secret, well then you wouldn't know who else it was. So, there's a kind of alternative form of illegality there as opposed to what the glory hole represented.

Braden Hill: And maybe there are opportunities too, because, I mean, when you think about our lockdown experience, you got an hour where you could go to the beach, and everyone was calculating the distance from the home to the beach. But quick visit to the public toilet, you never know. Might have been an opportunistic thing as well. That might have enabled that.

Lauren Butterly: And that really speaks to this idea that these kind of queer realities in public change a lot over time and a very temporal. And I know that's something that's fed into a lot of your work, Jo, this idea. And you were first involved when we’d just had legal change in 2002. And until I spoke to Jo in preparing for this event, I didn't really realise how much that legal change in 2002 had actually changed, how museums in particular felt about having queer spaces. Did you want to tell us a bit about that first exhibition you put together?

Jo Darbyshire: Well, it's very difficult, I think, for young people now to understand how difficult it was pre-2003. I mean, there had been law reform in 1998, I think, in Western Australia but it was only 2002 when the Government got rid of the last, I think it was— Age of consent became equal with heterosexual youth, and a few other things happened that we were actually considered equal. And it was then that artists and curators could actually then approach museums and art galleries about having something in their buildings about a gay and lesbian presence or history, because before that time it was seen to promote homosexuality and no one would touch it. Well, they were very brave, as, you know, the exhibition could have been closed by the police, for instance. So, yes, as soon as it was legal, I moved in [laughs]. I approached the Museum and said, Let me do something about the history of gay and lesbians in WA.

Lauren Butterly: And what obstructions did you face when you tried to do that? It wasn't an easy path, was it?

Jo Darbyshire: Look, the Museum was fantastic on many levels. And when I look back now, I think, wow, I got away with a lot. I think things have actually got straighter in museums and galleries than it was back there. But there was a lot of family values stuff that came up as a problem that, you know... The people that helped me in the Museum actually had to put out a lot of bushfires, basically. Fires about, oh, she can't do that, she can't do this, but we got it through. Yeah, there was all kinds of adventures I can tell you about.

I mean, one interesting thing was, right towards the end when the exhibition was nearly open, the attendants at the Museum nearly went on strike because they were worried that gay men were going to come into the exhibition and have wild sex [audience laughter] in the exhibition, in the WA Museum, and what were they going to do about it? Because it would be very scary for them. They didn't know how to handle the situation. Now, you know, we laugh to think that that could happen. If only it did. But no, it didn't. I knew that it wouldn't. And so we had to talk. We had a meeting with those attendants and, you know, I took them for a walk through the exhibition and tried to talk to them about, just how, you know, it was interesting, it was history, it was valid, that they wouldn't be embarrassed. And it was only when one of the male attendants actually recognised his uncle on an interpretation panel that the whole thing changed. As soon as there was a family connection, all the attendants were on board because they owned it. They could own it then. So it's quite interesting, the different things that happened with it.

Lauren Butterly: And that kind of, you know, personal connection to it that people were experiencing— Graham, your work in regional museums is really interesting too, because I know you were telling me before that lots of people know lots of queer histories, but they're not necessarily being told.

Graham Grundy: I think that's a fact. We've, we've have regional museum conferences, we've never talked about queer history. Of course, naturally, naturally, we're not going to talk in the country about it because we're 20 years behind Perth. But looking at the archives that I've looked at, there's certainly gay relationships. There certainly, there’s certainly sad gay deaths. There's certainly, that history is there. It just has to be uncovered. And of course, you know, genealogies, they write gay people out of the family trees because they don't reproduce, but still, they should be recognised.

Lauren Butterly: And I know in the context of discussing the glory hole, you had a few conversations around the Gay and Lesbian Archives about, was there ever any objects that were in the archives that people were hesitant to make public?

Graham Grundy: Well, yeah. When I talk to—’cause I'm representing Guy Gomez, who's the coordinator for the archive and he's more knowledgeable of this— so I did ask him that question, and he came up with certain things that he thought could not now be displayed. Interestingly, some of these were from the 1990s, and one of them was a wack brochure which showed an erect penis, which was quite alright then. But it seems that we've moved on from that and we couldn't accept that now. And also, there might be some lesbian material that was specifically made for lesbian eyes only, so that would not be, probably, distributed. So yes, there are certain things you, you have to have some sensitivity about [how] you can display or how you would do that. The point of it is that it's there for researchers and that's the critical thing. At least it's there and kept.

Lauren Butterly: And did you have similar conversations in your museum experience about certain things that there was a bit more policing around whether you put them publicly?

Jo Darbyshire: Look, I'm of the I understand that there are things to be sensitive about. However, I am completely the opposite. I think that every object can have a context in which it can sit. In fact, it can have many contexts. So something like the glory hole, I love that. I mean, I love low life history and so I could, if I was given permission, curate an exhibition about low life history, which is the history of prostitution, of homeless people, of, you know, people that are not considered worthy by society and so their history is not collected. But the other thing is that this fits into a whole lot of history that covers us right back to— Well, you can go back through policing. Okay, so the policing which joins onto vice, the history of vice in the 1950s. So before the 1950s, homosexuality wasn't a vice in that way. It just became very much more policed after the war, and that's when people went to jail—although they did beforehand, before that. But it was particularly bad in the '50s. But police themselves, you know. The whole the glory hole is, the door— You know, I can remember in Hyde Park, as you would if we saw plainclothes detectives in the park we knew that they were casing the beats and they were casing the toilets. And the word went around everyone in Northbridge very quickly. So that police beat, you know, that— This part of our history is part of surveillance and that joins into surveilling our sexuality. And so the larger context of this is sexual liberation, the sexual liberation movement. So, you know, there's always a context for any object, I think, especially to do with sexuality.

Lauren Butterly: Yeah. And I think we’re gonna come back a little bit later to talk about sex and sexuality and what that line is and where that kind of public/private divide comes in. But I want to bring us back to the door again. Mother Gretta, you've told me the door has an energy. What do you mean by that? What does that door bring to you now?

Neil Buckley: Well, it does have an energy. For me, it does. I mean, a lot of sexual energy, but also a lot of energy around discrimination and, like you say, with police violence. That so— [phone rings] Oh, God, that's my phone. Yeah. I thought I turned it off. Yeah, yeah. So I think it holds a lot of energy. I mean, it's been used by a lot of people so, you know, I think in that sense it contains a lot of energy.

Lauren Butterly: And lots of different emotions, I imagine.

Neil Buckley: Oh, yes, yeah, yeah.

Lauren Butterly: And everything from sort of the element of freedom and being able to I was actually I was at World Pride a while ago. Seems like long ago. It's only like, what, last week? Anyway, it was a great party. I saw the play about CAMP, the Campaign Against Moral Persecution and one of the comments that, you know, because I've had glory holes on the brain since, you know, I was facilitating this event. So I have been thinking about them a lot. And so I was at this play and one of the comments that one of the characters made in the play—now this was set in the seventies—was that the public toilets were the only place that this character, this gay man met people like him. And that's an incredible emotion. That must have been an incredible emotion.

Mother Gretta/Neil Buckley: Yeah. Well, I mean, that was a sense of community. I can remember that, you know, you'd go to the beats to have sex, but you'd also go down there to have community and, you know, speak to people. And I remember at Swanbourne, there used to be a beat patrol by the WA AIDS Council. At Easter time they used to come down, you know, with the bunny rabbit ears and pull of barbecue out of the back of their car and set up a barbecue. So, there was that real sense of community too. And I think, like you say, for a lot of people, that's the only way they could connect with other gay people and really find out what was happening in the community.

Lauren Butterly: Yeah, and I know Graham’s done a bit of research about how many beats there are within the sort of Perth metro area historically?

Graham Grundy: Yes. Well, I did download a hook up app, specifically for research, of course. [Lauren laughs] And yes, there are one hundred and, um—let me just get the numbers here—um, yes, one hundred and thirty beats within the Perth region and within thirty kilometres of the Perth region and another fifty within one hundred and fifty kilometres of Perth. So I think it's alive and well and happening.

Lauren Butterly: And we should say, you know, some of you might have been watching Australia on ABC and you know, last Tuesday night at 8:30 pm on ABC TV, they were talking about the history of beats. So, in some respects the conversations—and actually I think really, really recently, like quite recently—about these hidden histories are changing. Right. And why do you think it's important that we're having these conversations now about hidden histories and are we having them have they changed?

Braden Hill: Look, I think that queerness has always been within museum spaces and library spaces, and I think there are some ways in which it's conveyed and displayed that we're comfortable with. Right? So I think queerness in antiquity we're comfortable with because there's a temporal nature to it. It's a long way away. So we're okay with queerness and, you know, demonstrations of queer sexuality as long as it's a long way away. Because I think, my suspicion is, with elements like this, it reminds us that they are artefacts of kind of structural oppression that people have faced that have been within our lifetime. And we kind of— There's a sense of being complicit in that, that I think makes us uncomfortable whether we're queer or not. And I think for straight people particularly, it's a reminder of the fact that their family and members of their community have lived through really difficult times. And it's kind of reflected in the discomfort around this, you know, around this kind of item being in a collection.

So, I think it's a reminder of the fact that we, I think, we've kind of gone for equality and sort of forgotten liberation aspects. That's really interesting. And that's where the discomfort comes in. I think the idea of the nineties brochure being okay but that not being okay now says something about how we've mainstreamed queerness in some respects and it's probably not for the better. But I think this is a reminder of our discomfort, of our contemporary inaction, really, to do what's right in society generally, I think.

Lauren Butterly: And the door has been used, Mother Gretta, for— You've made a movie and that had sort of an element of education, safe sex education, as well. So you've used it for other purposes as well.

Mother Gretta/Neil Buckley: Um, yeah, made a short doco called The Other Side of Glory. I've got it here on USB, but they won't let me show it. [laughs] Yeah, yeah, we used it for that. We also used it with our sister house, as an altar. So, yeah.

Lauren Butterly: And that distinction that Braden brought up there about that kind of, you know, looking at that history and looking at that separation of liberation and things. And it also comes to this sort of sexualisation element as well. And I know that's something you're really interested in, and in particular, you're interested in it, not just from a sort of gay identity ide but also just more generally for heterosexual people. They find sex quite difficult in a museum.

Jo Darbyshire: I think they do. I think the museum finds sexual sexuality and sex difficult to talk about unless it's with animals. [audience laughter] The Museum has what I think is a fantastic object, which is a condom from the Second World War. So it's very rare, and can never be shown because it's falling apart. But when I saw it— It's very old. It's been used. [Graham laughs] But what was interesting was that these condoms were given out to the soldiers when they went to war. They were given a little package with five condoms in, or something like that. Here you go, off you go to war. And luckily they have one of these packets in the Museum. Now, why isn't that on display, for God’s sake? It's so interesting. And because it interrupts the dominant narrative of the Anzac hero. You don't want to know about them going back, going over there and having prostitutes, you know, having sex with prostitutes in France and then coming back with, you know, VD or syphilis, which many of them did. Many, many. So if you've got, you know, family history of a soldier, you look up their World War One records and you'll see that they were in hospital quite a lot where they had VD, and it was perfectly acceptable. So, I mean, why isn't this— I think that this kind of stuff should be part of the museum. I think sexuality in general should be talked about more. And then we have a context to include homosexuality or transgender issues. You know, our sexuality doesn't just start in when we got same sex marriage, it is part of a general sexuality.

Lauren Butterly: It's also quite interesting to think about what has been allowed. Right? So when you go to Kalgoorlie, everyone goes to the brothel museum there. You know, when you go to Kalgoorlie, that's one of the things on the list, that's one of the things that you do and you talk about and that's sort of accepted.

Jo Darbyshire: Well, when you go—and I am with Braden in that, as soon as something becomes mainstream and it's sort of prettified or sanitised, it loses its frission, its power. And I think what you've got here is something that has a lot of power still, because it is it talks about sex, gritty, dirty, you know, as the Premier said, tacky sex. Let's celebrate that. That's what sex is like sometimes. Right? But it's, you know, when you go to that brothel in Kalgoorlie, I've been there and it's just, you know, one pretty room after another. You can't actually imagine anyone having sex in there. It doesn't talk about the Japanese prostitutes that were taken to Kalgoorlie and nearly starved. Well, they were forced to be prostitutes. You know, it doesn't actually tell the dark side of the history which we need to understand how far we've come.

Lauren Butterly: There are different ways of representing. And so, the tacky, the comment by— It was an opposition minister at the time. We've got to be careful about that. “Tacky”— What do you think of that Braden?

Braden Hill: Look, I think following that logic, I think queerness for a lot of people is fine as long as it's palatable, as long as it's respectable, right, so we're comfortable with it. And I think this is what the challenge for a glory hole in a museum would be, is that it's not it's not straightwashed gay stuff, you know what I mean? It's this kind of real depiction of sexuality. And one of our histories that must be told right? This whole place is called Boola Bardip, many stories. That doesn't mean you just include the palatable stories. It's about how do we disrupt what these kinds of institutions should be. They've done a great job in recent times of making them more open, inclusive, and telling those kinds of narratives. But that means talking about sex and being okay with that. And, you know, I think the reluctance is a result of the fact when you look at our education system from primary to secondary, we are still really reluctant to talk about LGBTIQ+ anything in curriculum. It's a nightmare if you're a teacher in that space particularly, and that kind of means you have a whole bunch of graduates who come through the university, for example, who've not experienced any of this. And so where can they learn, if not at school, if not at university? Then maybe museums are space, you know, maybe that can be a really authoritative knowledge space that can that can engage people in interesting conversations. And so, I think the tackiness is great because it's one of our many stories that should be told.

Lauren Butterly: And certainly, you know, in terms of that experience of the education sector and the tertiary education sector as you're in now, what has been your experience of that, of students coming in with different knowledges?

Braden Hill: So, I was a high school teacher. I left teaching in high school because being an out secondary school teacher is tricky and at the time when I was doing it, particularly, I was supporting a queer Aboriginal kid who came out. The principal’s concern was that the parents would view me as turning that person queer. And I remember kind of thinking, Okay, this isn't the space for me. I loved being a teacher. Anyway, a job in academia came up. But there's a lot more openness within academia to talk about this. Absolutely. But I think in the same way we've seen that shift of conservatism around queer stuff, generally, I think universities have gone the same way in many respects. So, I constantly talk about, with colleagues who do jobs like mine, about how we are actually falling behind what is prior knowledge so, around general equity inclusion, queer stuff. We have students who come in now knowing much more than the professors about queer lives, queer histories. We are not keeping pace and I think that's a real problem. And it's a real, you know— People are learning more off Tik Tok than what they are through their schooling curriculum or— I'm not joking, you know. So, I think it's a real failure of our education system to do proper inclusion in curriculum, to talk about the lives of the people that are around them, you know. So, it's a real failure in our education system, I think. But, you know, things like this spark the right kinds of conversations to change that.

Lauren Butterly: Yeah. And thinking about those reflections and reflecting on your museum experience in 2003, how does it feel to look back on 2003 and look at this conversation that we're having today about something in the archives and whether it should be permanently displayed? How does that feel 20 years later?

Jo Darbyshire: Oh, I have a lot of mixed feelings. When The Gay Museum finished, I asked the Museum if they would like anything from it and they said no. Now, that was a terrible, terrible shame. I just didn't have the energy at that time to fight that because they could have had a lot of things in their collection. They do not have hardly anything, but the things that... Um. I don't want to be— Can I just say one thing? Braden talked about a good education and what they've done here with Aboriginal history, I think is fantastic and the approach they took was to take a male and a female curator, Steve Kinane and Michelle Brun, and those people worked with the collection and they— What they did was they embedded Aboriginal history into every aspect of this museum.

So every bit of history has got the Aboriginal connection and history and stories to it. And they also had a separateness to it. So, the entrance over there where you read the video stories, it's great, it's all Nyoongar, right? It's a special element just for them and I really wish that we could have the same thing for gay and lesbian, queer people, where we had the even the word lesbian actually in the Museum. Do you realise that the word lesbian is not mentioned in this museum? I feel so angry about that, that we're in 2023 and I did all that work 20 years ago and we still don't have it. So what we have is the LGBTQI corner. A fucking corner. Now that's not good enough for me. I have complained about it, as have other people. But the money's run out and there's not even any Aboriginal history of queer, which there should be as well, because that's a big history, isn't it, Braden, in this state? So that is a shame in itself. But yeah, I think a lot more could be done to completely redo [laughs] that. But I don't know if that's ever going to happen because... Well, you know. Do you agree with that?

Braden Hill: No, I do. So, I must admit, I didn't have much to do with the kind of discussions about the naming of this place. But I remember thinking, Oh, great, they're just going to slap a Black name on it and be like, look at us being inclusive. But I do remember when I came in and saw that that space and the really intentional and nuanced and complex way in which they integrate it into the, you know, the displays and all the rest of it was really powerful for me. Like all the research still shows that for queer young people, visibility, representation, seeing the flags, seeing themselves in their spaces is still vital. And I think when I walked in and saw Nyoongar people that I recognised, my own community in a space that generally would only have a Black person in it to show ‘em off as an artefact of colonialism, that was powerful for me. That was like, Shit, this is a space that could be a space for my community. And the fact that we lack that for the queer community is a real problem.

Jo Darbyshire: They did it so well, and the fact that they had a woman curator as well meant that the women's perspective, women's business, was on an equal platform to the men's business, which is unusual historically for museums. So, that, they did that so well.

Lauren Butterly: And I know as well, that your idea of, you know, everything not being, you know, straight immediately. You know, it has to, until we have a look at, yeah— And looking at everything through a potentially queer lens. It also lends itself to that conversation about, you know— A corner separates us. A corner kind of puts us into a separate location. Whereas, you know, part of your first exhibition really was to kind of queer the Museum in a sense that you were taking things from all over the place. Does that make a difference, the way that it's integrated?

Jo Darbyshire: I think it makes a huge difference. I mean, initially when I said I wanted to take everything, something from every department, that was just met with incredulousness, because it was seen that, you know, some of those departments, the biology, zoology, they dealt in facts. They didn't deal with, you know, social history. But it was only when I found that little crab. I found a crab that was called a shamefaced crab. And I thought, this is not a scientific fact. Somebody has named this, you know, and I can use it. So, and also, the fact that when I first came, they said, Well, look through the catalogue, put gay and lesbian in and see if we've got anything. I did that. We had one AIDS t-shirt from South Australia. And they said, Oh well you know, you can't really do the exhibition then because we don't have anything. I'm like, Well, what about everything you've got in the in the whole museum? And they said and they just looked at me and I said, How do you know that all those objects belong to straight people?

The assumption in museums is that everything is straight. Everything belongs to a heterosexual person. Even every chair, every everything. And of course, how can they prove that? They can’t. But what they were doing twenty years ago was saying, you must prove, you can't use anything until you prove that that belonged to a gay person, which is impossible. So I just made it up, basically. [audience laughter] I just put things together and said, I'm putting this in and I'm saying it's gay. [audience laugher, applause]

Mother Gretta/Neil Buckley: I came to that exhibition.

Jo Darbyshire: And one of the scientists actually said to me, because I had— And I did do everything properly as well. So, I had a video in there, made in France. It was called Out in nature, and it talked about the dominant narrative by scientists in nature, that they always had to show that animals, fish, everything, was naturally male and female and heterosexual. Which was absolute bullshit, which they now admit. So, this video was talking about this and one of the scientists said to me, This is actually a relief not to have to do this dominant narrative anymore. And he brought out this bee that they have in the collection, and it was called a gynandromorph bee. It was a male and a female bee on— The same bee. One half was female, one half was male. I mean, how fantastic is that object? But that was the only time they've ever been allowed to put it on display or talk about it, because it interrupts that dominant paradigm that every, that homosexuality is unnatural.

Lauren Butterly: Certainly, I mean, the gay penguins are now very famous over in Sydney. Very famous. And it was going to bring us back to what we were talking about before in that interaction of First Nations and LGBTIQ communities and, museums are complicated spaces. And I mean, all of you know that and not just for queer people in queer histories, but very much for First Nations people, too. And it's interesting the language that we’re using tonight about kind of dangerous objects and sort of, you know— Whereas we might say that many museums—we’ll broaden it out to museums more generally—are full of dangerous objects and dangerous ideas. Braden?

Braden Hill: Not just dangerous. Just awful things. Yeah. You shouldn't be putting up on walls and, you know, celebrating— You know, we named spaces after horrendous people, but we can't have a glory hole in a museum. You know, look, I think there's a whole movement around rethinking what these spaces should do. You know, decolonising museums is a really important conversation I don't think we've fully having here in Australia, in the way that's happening in the UK and elsewhere. But look, I think there are a lot of lessons to be learned in the way we approach that, in the same way we’d approach thinking about queer stuff in a space like this. So, I think there's a there's a lot of transferrable learning across those two ideas that I think we need to pay more attention to. And you can do them at the same time. I think your point about having queer Indigenous histories in a space like this would be phenomenal. I think that that would be leading and I'd welcome that. I think your point about the booka, do you want to tell that story? Because I think that's really cool, actually.

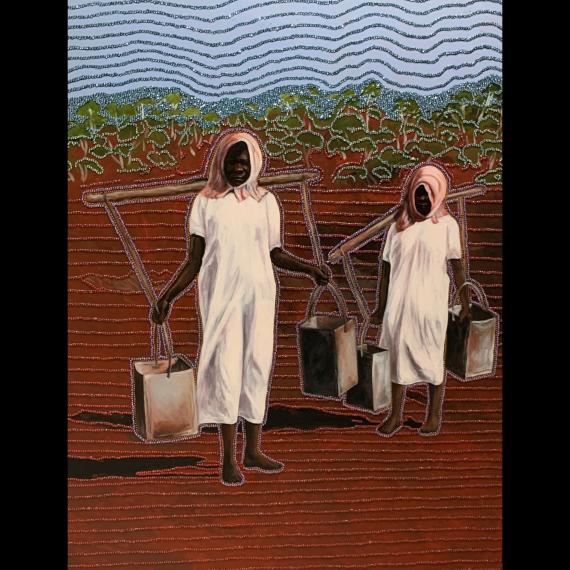

Jo Darbyshire: Well, when I approached Anthropology here—who were fantastic, by the way—they were very nervous about me talking to the Aboriginal advisory group and they did, they were very worried that I was going to offend them by asking if they wanted to be involved in the exhibition. So, it took a long time for them to organise for me to meet that group. And when I did, I was just myself and said, Look, I'm doing this exhibition. I'd really like to have Aboriginal involvement in it and I want to talk about, you know, your history and of course I want to run everything by you that I've found. And I know there's quite a few people in the gay and lesbian community that are of Aboriginal descent. And now, there are some amazing people on that committee. One of them, Noel Nannup, who I'm sure you all know— I don't think he'd mind me saying this, but he burst into tears at the meeting and he said, I can't. I totally want to support you, but I can't be in this meeting anymore. I've got to go because one of my nephews just committed suicide in the country because of his homosexuality. It was twenty years ago. But he said to me, This is very important, I want you to do more about it.

Ken Colbung, who— Most amazing person. Leader in the community and activist for many years. He was also on the committee, and he wanted to support it. At that time, Robert Smith, who had been—I think he just died last year. An amazing Aboriginal activist. He approached me. He was a sistergirl. He approached me and wanted to put his sistergirl outfit, that he'd won some prize for, in the exhibition. Now, Ken Colbung heard about this and he said, I want to make a booka for him. I initially asked if I could have the booka—Yagan’s booka, the famous Yagan’s booka which, you know, has another complete history, but I wanted to use it in this exhibition and he said, You can't use the original one because it's too precious and conservation won't allow it. But I will make you a copy. So, on the images out there you can see the evening dress, Vanessa’s evening dress, with the booka over the top. So that was an incredibly inclusive gesture by an Elder to the community, and which I thought was amazing.

Braden Hill: Yeah. And I think there's always this... Let me just, just speaking back, you know— I’ll take the First Nations microphone while I can. I think there's often a presumption of a lack of inclusion around queerness, especially when it comes to Elders, even within our own community. So, my research kind of shows that a lot of Aboriginal people assume that Elders, community leaders, are not going to be interested in having that kind of conversation. But what I think, what I think has been really important is that in engaging in those conversations with Elders there's been nothing but interest and openness. And one of the things that has always pissed me off as a researcher is, to get things done you have to go through an ethics committee and they tell you whether or not your research is ethical, right. Now, this is research led by queer Aboriginal researchers going to a white ethics body that said, Braden, you can't do that. That's going to be, that's going to be really difficult for you. It's going to upset the Elders. And you kind of— Think about it. If we walked away from that, we wouldn't have the knowledge captured. We wouldn't have the insights of what it's like to be Indigenous and queer in the here and now, because an ethics body got too concerned about what a vulnerable community, how they would respond to difficult conversations. And that's just bullshit, you know. So, that presumption of people's fragility is a real problem, not just in the research and academic space, but in this kind of conversation too. Engage people in dialogue gently and they’re likely to come along with you if you have a good heart and good intention.

Lauren Butterly: Absolutely. And that comes back from that, you know, the hidden histories element of at the beginning— When you actually start having conversations with people. And before this kind of started off, we were having a conversation with a few people around who'd said, they’d also had to explain what a glory hole was to people and they were surprised by how open people were. Starting those conversations surprises you often, what the response— You may have a presumption about what the response might be, but actually those conversations are often openers. And I should say that Jo's exhibition is, some of it, is on those slides as you walk in the door. So make sure you take some time in the drinks after this to have a look at it and perhaps ask Jo some questions. I'm sure she'd love that. Because it's important for us to have a look. Now, one of the slides on there actually has another little story to it, which will lead to another slight discussion point. The oyster, Jo.

Jo Darbyshire: The mussels?

Lauren Butterly: The mussels.

Jo Darbyshire: Well, when I was in, I asked if I could look through all these specimens in, what's it called? The marine biology area. That was fantastic. I was given carte blanche. Yes. Go in there. Have a look. Take whatever you want. Which was absolutely amazing. And when I got in there, I found these incredible mussels. And you can see the image of them up there with tongues and vaginas, and I thought, Oh my god, I have got to use these. These are perfect. I don't even need to talk about cunnilingus. I could just put this up there, right, and it would say it all. So, sometimes you don't have to be, like, hit people on the head. You can find things that are incredibly explicit in a way. And it was really interesting because I talked to one of the older curators, very, quite an old lady. I think she's still here as a volunteer. She told me that the early specimens that they collected were named in about, I think it was, 1819. Yeah, 1818, named by a scientist called Lamarck and they were called vagina such-and-such and labia such-and-such, you know. They were actually named for what they look like. And so we've— And she said, we've sort of censored ourselves over the years as scientists in terms of using these names. So, you know, they were very sexualised objects.

Lauren Butterly: And they were also objects that people instantly recognised and told you as such. Was that right?

Jo Darbyshire: Well, another story about Ken Colbung. He rang me up after he'd seen the cover of the catalogue and said, Oh, can I have a personal conversation with you? I was like, Oh my god, an Elder from the Aboriginal community. What's he going to say? He came and said to me, I just want to ask you, that cover, you know the picture on the cover, is that what I think it is? [laughs] Which was just beautiful. I said, Yes, it is. And he laughed. He said, I thought it was. I think he even said, I think I've won the bet. [audience laugher] So, you know, people did take it with a sense of humour, which is what I wanted.

Lauren Butterly: And I guess that opens up another conversation, because part of tonight is also about thinking about inclusivity of our LGBTIQ community. And so what kind of hidden spaces are there out there? Let's say you particularly focus on the lesbian community. What sort of hidden spaces might be around that might be portrayed in a museum?

Jo Darbyshire: I don't really know what you mean.

Lauren Butterly: You know, in terms of, you know, are there objects akin to the glory hole for other parts of the LGBTIQ community that might meet similar conversations in whether they're displayed or not?

Jo Darbyshire: I think the word dyke is pretty difficult for the museum to use. I mean, they obviously can't even use lesbian, so I don't think they're going to use dyke. So I think, you know, getting the dykes on bikes in here, yeah, might be good. Look, I think things have changed a lot, but I think the sanitisation is the problem. And the Museum itself historically has a problem with the— Sanitisation comes from not wanting to have anything to do with bodily fluids. So, I think that's another thing to do with the glory hole is that it is symbolic of bodily fluids. So, you know, it has to be in a context for it to work, a good context and a clever context. Things like the corset that you saw there, in the image. The Museum never shows a real corset that has blood, sweat, wadding on it where women had to pad it so they weren't in agony the whole time they wore them. They don't show that because they don't want to show that connection to the body and bodily sweat.

I wanted to— I had a fantastic man called Ron Mills, he gave me a book that he'd written about being a rent boy in Melbourne in the forties, 1940s, and in it he had a picture of himself with some red bathers, woollen bathers. So I wanted to get those. I wanted to get an example of those. So I came to the curator here and said, Do you have any men's woollen bathers from the 1940s I can use in the exhibition? She said, Oh yes. She said, Oh, but actually that's so strange because we've just got a pair there that we're not going to accession. And I said, Well, why aren't why aren't you going to accession them? They looked great to me. She said, Well, look at the stain on the front. [audience laugher] And I looked. On the front and, right there, was a fantastic stain and I just went, Oh my god, that is perfect. Because I want to put that in the section about beats. Now, you can just imagine her face. I mean, it's the complete opposite of what they would normally do. And I'm not judging her because I think this is the— That was the Museum way and it probably still is. But things are sanitised in general. So, they don't have a great history of looking at bodily fluids.

Lauren Butterly: And this sanitisation really plays out in the kind of work that you're doing, Graham, heading out into the regions where the kind of conversation that we're having tonight, you hope, can kind of go further into starting some conversations in those regional museums. Tell us how they kind of operate.

Graham Grundy: I’d just like to comment on what Jo said there. I think it's interesting. We probably have things in museums that we have to reinterpret. And a classic thing recently you may have seen the darning tool that was found in Roman Britain is actually a dildo [laughs] but those are the sort of things that perhaps need to be interpreted. But yes, as far as the regions are concerned, I think we really do need help from the WA Museum. We used to get it, you know, with traveling curators and things like that, to help manage museums, reach those small museums. But I think now we need, really help to address this. How are we going to manage these and find, you know, LGBTQI information and how we can do it?

Lauren Butterly: Because how do you feel like a conversation like this one would go down in some of your regional museum committee meetings?

Graham Grundy: Interestingly enough, I've had some conversations with my committee and yeah, they're absolutely over the moon with this. They think this is the greatest thing that's ever been done. Really. They're very, very enthusiastic and very supportive of it. And so... I mean, they know I'm gay. Of course. And it doesn't matter. We work together and we just manage a museum. But we've never really talked about any gay history or anything gay. We never have. So maybe this can open the door to that conversation in regional museums, too.

Lauren Butterly: And the door being more than an object, then? The door being an opportunity to have a bigger picture conversation, not only in Perth.

Graham Grundy: I think it is, yes. I think that door can lead to those conversations. But interestingly enough, Mother, could I just say one thing? We're thinking of this as a gay item, but really, this is really an item for men who have sex with men. And the question is, you know, the gay community has owned it, but does it really? Is it really a real item that belongs to the whole community?

Mother Gretta/Neil Buckley: Well, I mean, if you really look at it, it's something that was created by straight men, because it was the laws that straight heterosexual men made that were actually a reason for this to exist. So you can say the glory hole is straight.

Graham Grundy: Yeah, yeah. I mean, I think people attending sex clinics, only 40% actually identify as gay. Yeah.

Lauren Butterly: And I know for you, you said the door brings up lots of different emotions.

Graham Grundy: Yes, I think I was conflicted about it. You know, it is quite a— Let's just go back to the beginning. When I first heard about it, I found it confronting, you know, that this tacky item was going to be kept. But the more I thought about it, you know, I thought, well, no. Yes, it does represent a certain community and it is important, and even if it's not displayed, it has to be maintained and kept in the Museum collection.

Mother Gretta/Neil Buckley: Do you think in about hundred years they'll bring it out?

Graham Grundy: Yeah. [laughs] Yeah.

Mother Gretta/Neil Buckley: It'll be acceptable in about hundred years.

Lauren Butterly: And also, Mother Gretta, you donated some other things alongside it as well, didn't you?

Mother Gretta/Neil Buckley: Not alongside it, but we donated— I was part of the team that donated the AIDS memorial quilt to the Museum. And that's another thing linked to gay sexuality, and they’ve sort of mothballed that, as well, which is a bit of a shame. They need, they actually do need to show that.

Lauren Butterly: And that's become part of a whole other sort of set of histories that is actually commemorated in a lot of different places and in a lot of different museums around the world. I do want to come back to this idea that I know Jo's really interested in, this kind of public-private idea and this idea of, you know, what is sex in public? What is sex in private? You know, how do you feel about that with the glory hole? Is it a public item? Is it a private item?

Jo Darbyshire: Look, I think this is the interesting thing about sex is that it is both private and public. And I think that's something that, curatorially, you have to think about. For instance, even people that we think of as heterosexual are a little bit dodgy, often. And, for instance, I think I think a lot of things are going to change because of the way that younger people are opening up the debate about sexuality and not accepting any one or the other. And— For instance, you've got, there's a mention upstairs about someone who, I would say, or would own as our most, Western Australia's most notorious lesbian. Does anyone guess who that is? That would be Shirley Finn, who's also our most notorious madam. But the thing is that Shirley Finn is considered, she can, she performed heterosexuality. She performed heterosexuality as a madam, as a prostitute. However, in her private life, she lived with a woman and had relationships with women. So I can't speak for her and say she was a lesbian, although I'd love to. I probably will. [audience laughter] But you can't claim her as heterosexual. She was complex in her sexuality. And I think this is the way that we're all going to have to rethink a lot of people and a lot of things that we're not necessarily straight or gay, we're fluid. Sexuality is fluid.

Lauren Butterly: And that's a conversation that you have a lot in regional areas, isn't it Graham? Where people have these histories that are there but not being represented.

Graham Grundy: Well, absolutely. You know, you can— As I said before, you know, just looking at archives and researching, you can see a pattern in somebody's life. You can't prove it but you know there's something going on. You know, two men living together, you know, for forty years or we're looking at somebody— A young man goes out, you know, to search, you know, to manage the windmills and then shoots himself, you know, on this trip. What's going on, you know? But it's hidden. We don't know. We can't prove it. We can't find it.

Jo Darbyshire: Certainly Trove is opening up a lot of doors. You know, treasures. You know, the newspapers. Because you see a lot of that criminalised behaviour. And some people are doing research on that. In the forties, a lot of young men were sent out to isolated farms to work on them. And there's quite a lot in the papers about, you know, those people being investigated by the police, and abuse, and all kinds of tragic things happening on those farms. There's a lot of hidden history.

Lauren Butterly: Absolutely. And when we think about more contemporary hidden histories, Braden, what do you think in your research are some of the hidden histories that you bring to light? Or maybe sometimes in the tertiary sector, as you said, some of your students are bringing knowledge is beyond what they might be about to be taught at university. What are some of the hidden histories that we're starting to see now?

Braden Hill: Look, I think the obvious hidden history is that, you know, there are Blackfullas who are queer. I think that's a public conversation that is starting to happen. You know, research is very new in kind of that space, so, I think that's an important hidden history. I think, you know, Graham was talking about how, you know, racism and, kind of, homophobia worked in tandem to really criminalise Aboriginal people's lives. We were talking about the one incident in history of two Aboriginal men who were criminalised for, you know, sexual acts when really they just went to the toilet to have a drink because they weren't allowed in the public bar. But the cops did them on sexuality, on kind of sexual grounds, of their sexuality. So, like those sorts of stories are really interesting. But I think, I think there's a— I think our lives are documented in ways they've never been done before. And I think the generation, the younger generation now, there's a very evident narrative that accompanies their real life that's going to be hard to delete, right. It's part of who they are, their identity, their sexualities.

So, it's going to be— I think, I don't know what the hidden histories are. I think we've talked about a lot of them. But I think what's really interesting is, what are those histories going to look like in the future when lives are just so documented now? Those stories about, you know, the lesbian couple, you know, who run the bowls club at the local, regional, whatever, that's going to be the Tik Tok of somebody's life going forward. And I think that's going to be a really interesting... I think there's going to be a really interesting kaleidoscope of those stories that are unavoidable, right, because there's no mistaking what they are. It's very clear and upfront and obvious. You don't have to interpret a tool as a dildo or a dildo as a tool. [laughs] You know, it's going to be very clear.

Lauren Butterly: Instead of the archives of the newspapers, it's going to be the Tik Tok archives. Can you imagine? Do you think that— Yeah, absolutely. Do you think that the—when I say the current generation, I'm not entirely even sure what that means—but there's sort of these newer generations now thinking about sex and sexuality in the same kind of delineation that we've spoken about tonight and that discomfort of talking about sex? Or do you think that it's changing, that narrative?

Braden Hill: So, look, I've worked in universities for fifteen years and it's not a long period of time, but just over that period of time, it's changed significantly. So, we do a lot of stuff. You know, we ask students for their feedback on their teaching and learning, the experience. What I’ve found in that is there's an expectation that you will talk about queer stuff. It's not acceptable anymore, that you have a whole school that's dedicated to medical and health science or nursing and midwifery, and you don't include conversations about the lives of intersex people encountering the health system. That's a clear expectation that wasn't there ten years ago, and I think academics are having to catch up with that, as I said before. So I think I— I don't— My argument is, I don't think that's coming from education. I don't think teachers are opening up that space for dialogue in the public system particularly, or the system at all. There's something else happening, whether it be popular culture, social media, those networks. They're coming with that expectation that they will be learning about that because it's right. And I think that's what's changed. And that's just in my time, that I've noticed, and that's what gives me hope, I think, is that they're going to go off and become our curators, become our doctors and lawyers, and they're going to have that expectation. Certainly not— It's not everybody. We still get the backlash of people saying, Why do we have to do this queer shit? Why do we have to study Indigenous people shit? But it's the minority. And it’s becoming more the case, I think.

Lauren Butterly: And how do you feel about that in the curatorial world? Has that kind of come through in the curatorial world as well?

Jo Darbyshire: Well, you can see the proliferation of queer exhibitions in the eastern states and there is a— Craig Middleton has been employed as a curator at the National Museum and he's a senior curator and he is gung-ho about queer stuff and is collecting for their collections. He's actually collecting for their collections. That's very different to having temporary exhibitions and queer nights where people come and be queer for a night in the museum. And so I think there is a big movement to let queer people into the museum and encourage them to come in. But it's a bit like Aboriginal people. I didn't see many— I have never seen many Aboriginal people coming to the museum on their own, very much. That's starting to change now. But it only changes when things of integrity happen, because you don't go to something for a very, you know, a pop-up queer night and you know that there's going to be a drag queen there. It's like, that’s not really history. People don't want that in the museum. They want real stuff, real history. I think, anyway. So I think to answer your question, it is happening in the eastern states, but I don't know whether it's happening well. I don't know if I've explained that.

Lauren Butterly: Yeah, I know. I mean, I think— So, Mother Gretta, you talked a little bit about the international response, and I know that you spoke to The Voice this week as well, just as a kind of follow up, a newspaper about what was what was happening. And is there anything else like the glory hole in the world, that you know about? Do you think that is why it got the international press?

Mother Gretta/Neil Buckley: Um, I'm not sure whether there's anything else. But like I said it was great international press and great press for the Museum, so I'm bit surprised why they want to keep it in the closet, because it's such a positive international response. It was huge in the UK, the US, Cuba of all places. I had a friend who went to San Francisco and [someone] said, Oh, your photos in the local gay newspaper. Oh, okay. So yeah. So I'm a bit surprised by the Museum— As you know, when you think about it, you know, like one of the most searched things on the Internet is sex. So if the Museum had something about sex, just imagine all that. The men that would come, you know, you'd have a creche downstairs. They could drop the kids off at the creche and go up to the sex exhibition. Attendance.

Lauren Butterly: Well, I mean, that's something that that Jo thinks is an interesting idea. Sort of having kind of an exhibition more about sex and sexuality for everyone.

Jo Darbyshire: I think there should be an exhibition about sex. You could call it Sex in the City but we'd have to include the country. But, you know, sex generally is interesting. And as I said before, you could then explore everything instead of just, instead of just sexual identity. Right. So it's easy to be out on a gay march, but it's difficult to talk about how we have sex as gay, lesbian, queer people. It's very difficult to talk about that private part of it, which often is connected to love and humanity. So, that's where I think it's just too hard for the Museum, unless they get specific people and put a lot of money into it and think about it. It's hard work, you know, because it's difficult for any of us to even talk about it openly, let alone the Museum do something that is for the general population.

Lauren Butterly: And I know, Braden, you've just come back from WorldPride as well. Do you have any reflections on the way sex and sexuality was represented at WorldPride in relation to this conversation?

Braden Hill: Um. Look, I think, as we observed, I think it's interesting being in a bit of a bubble where you're the dominant majority and that's fantastic for somebody like me who doesn't get to experience that very often. But just seeing matter of fact queer lives expressed in a really important way, celebratory way— I think the way they managed to curate the history of Mardi Gras, the politics around it, was really fantastic and I think even just doing that in WA— We don't see it very often or very well done. So, I think they were, yeah, they were kind of reflections that I had. But I'm looking at your lapel with the Progress Shark who became a bit of an icon, right?

Lauren Butterly: Progress Shark was a bit of an icon.

Braden Hill: It was.

Lauren Butterly: An awkward icon. Yes.

Braden Hill: But again, a museum, kind of slapped a progress flag on a shark. But everywhere you went, you kind of saw these superficiality of queerness that kind of popped up. So the BW-Yaas. And like, all these other things where you thought, is that, is that like the best we can do guys? You know, but it was interesting. It was interesting. But it's not that authentic kind of telling of stories or celebration of queerness that I think we'd like to see. But I think the program of events that they had, the exhibitions they had, the histories they told, the presence of Indigenous queerness, a huge piece of art on the side of the building; that's just fantastic, I think, to do that, but it's nice to see that. But we just need to take threads of that and intertwine it everything that we do and not be afraid of it and not be scared of it.

Lauren Butterly: And I think one of the things they did do, they had a dyke bar and it was called a dyke bar. So that's one of the things—

Jo Darbyshire: The Museum could rename [indecipherable].

Lauren Butterly: And Mother Gretta, you also were at Mardi Gras and WorldPride. Do you have any reflections on that?

Mother Gretta/Neil Buckley: Yeah, it was great. It was a really good space. A lot of people. Yeah, just had a fun time. [Lauren laughs] I lost my phone at a certain place. [laughs] I won't go to that. [audience laughter]

Jo Darbyshire: Look, I noticed that in London at the moment they've just opened, in the last six months, I think, a gay and queer museum. And I have really mixed feelings about it. I haven't seen it, but while I think we need our spaces, our queer spaces and I don't want to see them go, it's like if they— But I also noticed that the Welcome collection, which is another big museum in London, is collecting things about prostitution, pornography, all kinds of things, so perhaps they are working towards having a big general exhibition about sexuality. But I don't know why we have to wait for the Welcome collection in London to do it. I mean, we could do it.

Lauren Butterly: So with all these, you know, fascinating topics of conversation— We've had quite a variety over the last hour and a bit. I am going to open it up to questions. Does anyone in the audience have a question relating to our discussion, to WA queer history, or about the door in particular? We should say that the door is actually very heavy. That is one thing that we know about the door.

Mother Gretta/Neil Buckley: It is. It takes two people to lift it.

Lauren Butterly: So and when you were planning, your getaway with the door. How did that go?

Mother Gretta/Neil Buckley: Well, we weren't planning on it to be so heavy. [Lauren laughs] And when you actually unscrew the hinges, of course, we buckled one of the hinges because it's so heavy. So we had a problem getting the hinges off the walls.

Lauren Butterly: It nearly didn't want to come. Nearly didn't want to come. Was there a question down the front here? Now, we do have a microphone coming from the back. It's okay. We're not going to make you run.

Audience member: Hi, my name's Gina. My question is for Graham and I noticed that when you were speaking, yes, you were talking about how, you know, you had a good relationship with the folks out in the regional areas and that was good, but I couldn't help also hear that perhaps you weren't seen in that circumstance. That you weren't seen— You were seen as a gay man, but it wasn't like your life was acknowledged in the things that were being talked about. And I just would be interested to hear your reflections on that, whether your sexuality and your life and, um, queer lives might be spoken about as you, as you pointed out, but whether or not there's a bit of a gap to there?

Graham Grundy: I was very fortunate that I had a lifetime partner who was born in Western Australia and dragged me back here. And so, we were the only gays in the village—that we knew of—but we had a wonderful life. But we never were out gay. You know, I'm talking ‘90s, 2000. We never out gay. We never talked about gay. We never expressed gay. We were just community people. And so, yes, I don't think my homosexuality was ever really acknowledged by anybody, to be honest with you. But it is now. You know, I'm clearly out and proud to my committee. I don't live in that community any longer. I live in Perth now. And as a matter of fact, I spoke to one of the committee people today, talking about this, um, the door. And she said, Oh yes, I'd seen it on the news. It's very interesting and I just think it's fantastic. And she said, As a matter of fact, I mean, she said, My husband was just amazed, to be able to work with gay people because he'd never experienced that before. He had this other idea what gay people were. But now he said, You—and this happens to be another member of the committee that's also gay—she said she sees how, you know, he's seen how you work and what you do. And I have that respect. Thank you.

Lauren Butterly: Any other questions? Oh, we've got a question down the back.

Audience member: Hello. Thank you very much for organising this event. It's been a real pleasure to watch it, especially for me coming back to Perth after some years away and to see this happening here in the Museum is really reassuring in some sense. I guess my question is more of a challenge, I guess, for the panel is, you know, thinking about the door, what it represents to me, I think, is probably shame. There's an aspect of shame there. There's an aspect of hiding. And I think reflecting on where we are now as a country, I guess, in terms of sexuality, there's this sense of openness. I, too, was at WorldPride the other week, and there was that real sense of openness in an international sense. But I guess, I've come back to Perth and I've noticed a real, real issue in the community around, around shame and around drugs and around, you know, some real deeply seeded issues of hiding. So, I guess, I guess I just wondered and wanted to get your perspectives on whether there was, you know, an element of this that is a bit darker than just pride. It's a bit darker than, you know, the openness of sexuality, that it's actually perhaps more so having to do with, you know, internalised feelings of shame, if you like.

Lauren Butterly: We'll give everyone a chance to have a go at this, because I think that this is something that we've come up with again and again. And we started by talking a little bit about Mother Gretta’s views on the kind of energy behind the door, which is really complicated energy and shame is a real part of that energy; and then these, kind of, other issues of context and time that we've discussed along the way. So why don't we start with Mother Gretta and then we'll move back to Jo and then back to Braden and Graham.

Mother Gretta/Neil Buckley: Well, I think a lot of a lot of the objects that you see like this, because we were so criminalised, perhaps this object does possess a bit of shame because when people look at it they just see a negative thing. Yeah, I suppose it does represent shame. It represents a lot of things which— And I think, and to actually be able to tell that story think is really important.

Lauren Butterly: I know for you, Jo, context is a really important thing.