In Conversation: Decoding the language of colonialism

An exploration of the importance of calling it as it is.

Many would argue that Australia is only now reaching a point in its history where the dominant culture is willing to make space for the possibility of raw and authentic truth-telling, specifically as it relates to Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander and South Sea Islander people’s experiences of colonialism.

We are in the long process of coming to terms with the country’s darker histories surrounding the treatment of Aboriginal people, a legacy which has deep roots in contemporary social and political structures. In the name of truth telling, when comes the point in this process where we start to replace words like “stolen wages” and "indentured work” with less illusive, more realistic words like "slavery".

Join a panel of experts and community as they discuss a hopeful new path forward in decoding the language of our written and oral histories in Australia and the importance of calling it as it is when it comes to the past and present.

Facilitator

Professor Alistair Paterson is an ARC Future Fellow in archaeology at the University of Western Australia. His research examines the historical archaeology of colonial coastal contact and settlement in Australia’s Northwest and the Indian Ocean. His key interests are Western Australia and Indian Ocean history, Aboriginal Australia, Dutch East India Company, colonialism and exploration, rock art, and the history of collecting in Western Australia in collaboration with the Western Australian Museum, State Library, Art Gallery, and the British Museum.

Speakers

Dr Carol Dowling Carol Dowling currently freelances at Noongar Radio 100.9, previously holding a Senior Research Assistant position with the National Drug Research Institute at Curtin University. She has worked as lecturer for over 27 years at Curtin University, Edith Cowan University and University of Western Australia specialising in Aboriginal arts, indigenous research methodologies/postgraduate studies, Indigenous human rights, politics and culture. Carol holds a Bachelor of Arts (Aboriginal & Intercultural Studies) from Edith Cowan University and a Master of Arts (Indigenous Research and Development) from Curtin University. Carol holds a doctorate in Social Sciences from Curtin University. Her area of PHD research is an auto-ethnography of five generations of Badimia women in her maternal family.

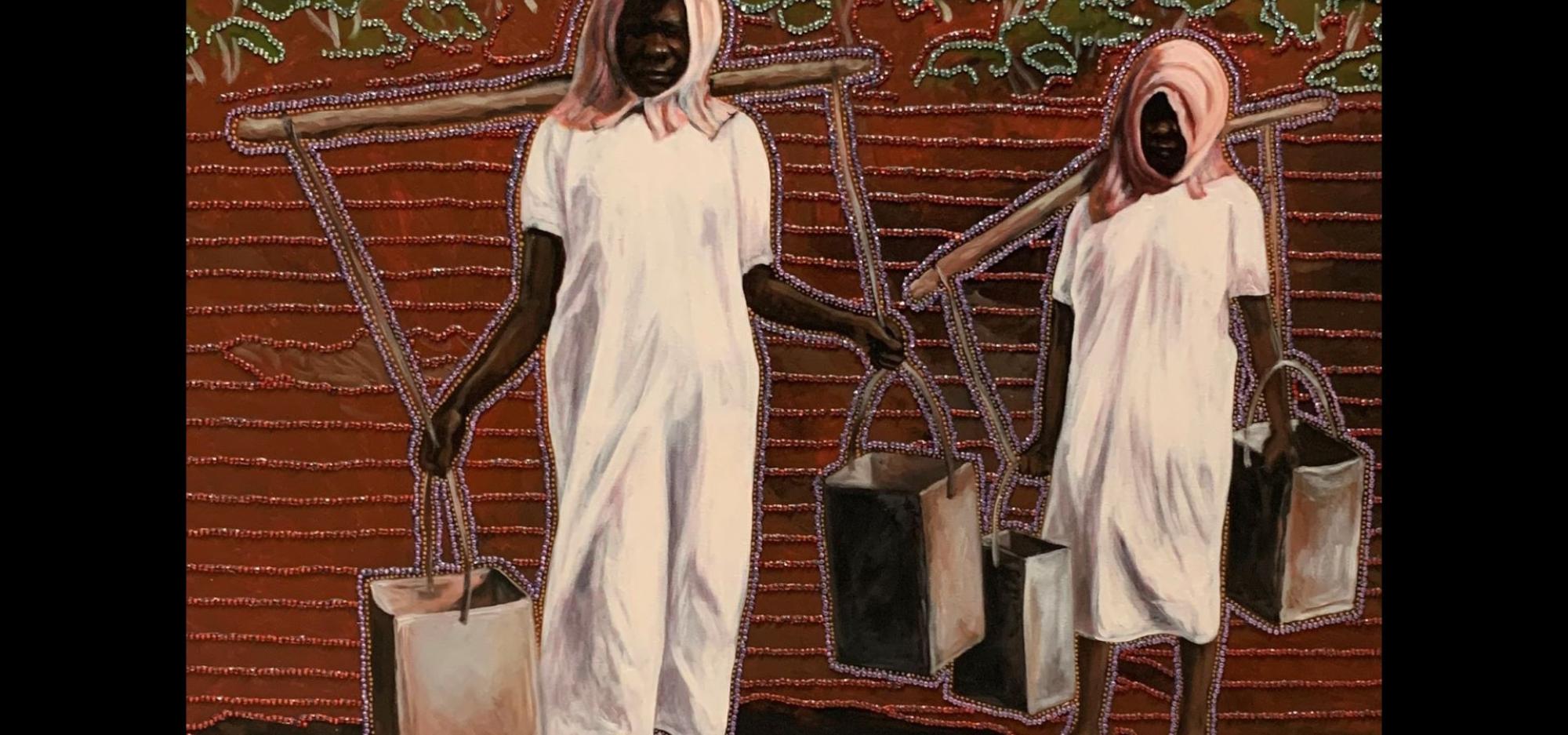

Dr Julie Dowling is a renowned Artist who works in a social realist style. Dowling draws on diverse art traditions including European portraiture and Christian icons, mural painting, dotting and Indigenous Australian iconography. Dowling works like an ethnographer, recording the deep-seated injustices in the Indigenous community. The featured image for this event is a work by Julie Dowling titled Dyilima Gabi (Carrying Water) and is described by Dowling as "...an image of two unknown young women walking water from a well or river for the use of their white boss men or lady. They carry tins full of water over their shoulders. This was a common job for many First Nation people as it was deemed a menial job for slave labour. This style of slave labour had already been universally outlawed in the 1860’s throughout the world but was still in effect in Australia up until the 1970’s. It could be argued that modern slavery of First Nations people still continues today.

Professor Jane Lydon is the Wesfarmers Chair of Australian History at The University of Western Australia. She is concerned with the history of Australia’s engagement with anti-slavery, humanitarianism, and ultimately human rights. Her work has contributed to decolonizing heritage and academic practice, with a strong impact on debates regarding colonialism and Australian legacies of imperialism and slavery. She currently leads the 'Western Australian Legacies of British Slavery' team project, which seeks to analyse Australian legacies of British slave-ownership by tracing the movement of people, capital and culture from the Caribbean to the settler colonial world. Her most recent book Anti-slavery and Australia: No Slavery in a Free Land? (Routledge, 2021) explores the anti-slavery movement in imperial scope, arguing that colonization in Australasia facilitated emancipation in the Caribbean, even as abolition powerfully shaped the Settler Revolution.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice

In late 2023, Australians will have their say in a referendum about whether to change the Constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice.

Be ready for the conversation, become informed at Voice.gov.au

-

Episode transcript

In Conversation: Decoding the Language of Colonisation.

Thursday 13th July 2023

WA Museum Boola Bardip

Facilitator: Professor Alistair Peterson

Speakers: Dr Carol Dowling, Dr Julie Dowling, Professor Jane Lyden

Pre- Recorded Introduction:

Welcome to In Conversation. A series brought to you by the Western Australian Museum Boola Bardip. In Conversation is a safe house for difficult conversations and passionate and thought-provoking public dialogs that tackle big issues and difficult questions led by some of WA’s most brilliant minds. In Conversation is recorded on Whadjuk Nyoongar Boodja. The Western Australian Museum acknowledges and respects the traditional owners of their ancestral lands, waters and skies.

*Recording starts part way through*

Professor Alistair Paterson:

….. is described by Julie as an image of two unknown young women walking water from a well or a river for the use of their white boss or lady. They carry tins full of water over their shoulders. This was a common job for many First Nation people as it was deemed a menial labour or slave labour. This type of labour has already been universally outlawed in the 1890s throughout the world, and we'll talk a bit more about that slavery in particular. But was still in effect really as a form of labour in Australia, well into the 1970s. It could be argued that modern slavery of First Nations people still continues today. That's Julie talking about the work. In 2002, Julie was awarded an honorary doctorate in literature from Murdoch University, and in that same year was named by Australian art collector magazine as Australia's most collectible artist. So, it's wonderful to have Julie here tonight and I've always really admired her work.

To my left, we have Dr. Carol Dowling, who currently freelances at Nyoongar Radio 100.9. So, we should be able to talk. Previously holding, um no, holding a senior research assistant position with the National Drug Research Institute at Curtin University. She's worked as a lecturer for over 28 years at Curtin University. Edith Cowan University and UWA, specializing in Aboriginal art, Indigenous research methodologies, postgraduate studies, Indigenous human rights, politics and culture. Carol holds a B.A. Aboriginal Intercultural Studies from Edith Cowan University and a Master of Art in Indigenous Research and Development from Curtin, a Ph.D. in social sciences from Curtin University and that research was an auto ethnography of five generations of Badimia women in her maternal family. So obviously, I just want to say that it's wonderful to have the perspective of these two sisters while they've worked in very separate fields. They've been a constant support to each other. And Carol reminded me as Badamia women that they're all about family and community. So, despite decolonization and healing, there remains racism and oppression that many communities continue to struggle with daily.

Finally, we have over at the far side of the stage, Professor Jane Lydon, the Wesfarmers Chair of Australian History at the University of Western Australia. Jane is concerned the history of Australia's engagement with anti-slavery, humanitarianism and ultimately, human rights. Her work has contributed to decolonizing heritage and academic practice with a strong impact on debates regarding colonialism and Australia's legacies of imperialism and slavery. She currently leads the West Australian Legacies of British Slavery Team Project, which will hear more about which seeks to analyse Australian legacies of British slave ownership by tracing the movement of people, capital and culture from the Caribbean to the settler colonial world. Her most recent book, amongst many, is Anti-Slavery in Australia. No Slavery in the Free Land, published by Routledge in 2021, which explores the anti-slavery movement in imperial scope and argues that colonization in Australasia facilitated emancipation. Emancipation in the Caribbean, such as abolition, powerfully shaped the settler revolution. So really interesting work coming of relevance to Australia.

And finally, I'm Alistair Patterson, your facilitator. I'm actually an archaeologist based at the University of Western Australia. As you're probably aware, there are many different types of archaeology. My interest is in the modern world and its roots and how heritage sites and landscapes and material culture allow us better to understand the human journey over recent centuries that lead to this moment in time. I spent most of my time looking at histories of globalization, such as through the Dutch East India Company, the kindly left four shipwrecks on our coast, or thinking about the nature of resource extraction from Australia's waters and lands and the ways in which labour was provided to underpin these industries.

And I should note that all of this work requires solid partnerships with communities, but also the West Australian Museum and its wonderful staff. All right, so that's everybody. So, here's how it's going to work. I have some conversation points and questions which I'm going to put out to the panel. This should allow them to explore the themes of tonight's discussion and as pointed out by our host. Basically, planting a seed and seeing where it goes. And after we've spoken for about 40 minutes or so, then we'll open it up to the floor. It's your turn. So please, with keep your patience to the end, I hope you'll have some questions for our panel as well. We have a range of ages here tonight from the very young through to the less very young. So, I invite people from each generation to ask questions and to make a comment by any request really is for everyone to be civil and respectful in those questions. Great. Okay, so let's get going. Umm, I'm going to start just with a little anecdote, because I want to start with the word to talk about terminology in this first part. And for me, you know, I've already mentioned slavery a few times, and it's a very powerful word. Um, I recently published um, a paper on the pearling industry in the Pilbara in the 1980s, uh, oh, about the 1880s and 1890s. I'm looking at some sites on Barrow Island where we published a paper with Professor Peter Veth with the word slavery in the title, and there was a bit of a media spin as there normally is with these events. ABC Pilbara picked it up, they ran it on their Facebook page and then I get a call the next day and it was from the ABC and they're just like,

“Are you really comfortable with the word slavery in the title?”

And basically, they were getting, you know, a lot of intense feedback on the are on their, on their Facebook page, which, you know, hadn't gone quite direction that they were hoping for. And I was very comfortable in saying,

“Well, yes, if you read the paper, we'll actually say that we've. The term slavery was used in the 1880s by people such as government registers in places like Roebourne.”

We said, you know,

“This is akin to slavery. What is happening in these workplaces is like that. So, I said, don't worry, it's in the historical record. You just point people in that direction”,

and thankfully they didn't actually change it. But it does remind me of the ongoing power of these words that something such as terrible as slavery can still kind of find such controversy in the present. So, I'll hand it over to the panel. You know, slavery involves incarceration. It's not you know; we see these photographs of Aboriginal people in chains in places like Roebourne and think about those places in the colonial era where those experiences occurred. So maybe we can just start with some terminology about, kind of, for our audience about these terms. What's the difference between slavery versus a more common term, indentured labour? I might say that with Jane on, on a terminology issue, and then I'll open it up to the others.

Professor Jane Lydon:

Okay. Well, thank you very much, Alistair, and can everyone hear me? I just want to, before I do respond, just pay my respects to the traditional owners of Whadjuk Nyoongar country, pay my respects to the elders, past and present. And I think that is particularly important. It's always important, particularly when we are talking about issues like these tonight and also to say what an honour it is to be on this panel with Julie and Carol. So, to answer your question about terminology, I just want, to as a historian, just want to go back to that moment in 1833 when the British government abolished slavery. So, for the British, that was a great triumph and a celebration. But I think what it means is that ever since we've had this binary between slavery on the one hand and freedom on the other, and that has obscured the spectrum of different labour forms that actually proliferated, that actually increased after 1833. So, you know, the great sort of self-congratulation and celebration of abolishing one form of unfreedom in some places meant that we have subsequently overlooked indenture and other forms of coerced labour. So that would be my answer. I guess that sometimes there wasn't very much difference at all. So, I'll hand over now.

Dr Carol Dowling:

Well, when you're experiencing oppression [laughs], you don't really care about the terminology and [laughs] okay, [laughs] I'm so glad to have my countrymen here. Thank you for coming…. you guys…. In Badimia country, ummm, the, the push for, for, you know, from from my understanding anyway, because I did this this little thing called a PhD, it took me 14 years and it was driven by my nana and she was 93 when she passed, uh our Nana and she started with me researching when she was 89 and very much brought me and Julia, uh, Julia and I up with these strong, very perplexing and for us, powerful oral histories and stories about survival of particularly the women in our family. And those stories in the scheme of things really shaped who me and Julie were. And she was thoroughly convinced that because we were fair skinned blackfellas that we'd be okay, we wouldn't have to experience anything. But the reality is we were witnesses, we were witnesses, we questioned, and we knew that, umm and in lots of ways, I feel that we we were able to have the freedom to comment on what really happened. And and I find that in the, in the PhD process, which took a very long time, 14 years. Umm, never research, your family...

Audience:

[laughs]

Dr Carol Dowling:

You basically, uhhh and plus you know, writing is not the same as painting. Okay. Julie is a fantastic painter and what takes me like and I 8000 words or whatever, she can just whip that up in an icon. But I often find that, you know, the stories that we were brought up with were so perplexing. I mean, I mean, one story in particular was so powerful was the one that our Nana told us about Her grandmother, who was the first, was our apical ancestor, as they call them, who was the first person in our family to have contact with white people in… up in our region, which was the central west WA, in Badimia country. Ummm. It was around about, you know, the, the, the first ventures up there was around about the 1870s. So, Lord Forest was trundling through there and all that sort of stuff but…. In that whole process, our apical ancestor was plucked out of the bush by her white master, and I referred to him as my master, even though he is my great, great grandfather. And he named her, and he said,

“I'm going to…. I like the look of you. You're going to come with me and I'm going to call you after my favourite town”,

which was Melbourne. So, he called a Melbin, m, e, l, b, i, n. And, and that story became even more potent to us when Nana said what she did because he, he took her on a boat and took her to England and they were there for a year and she, he brought her back and basically…. I always, it would always mess with my head, what Nana said then was the words that she said to him when she got back. She said to him,

“Go find one of your own kind”,

and to me, it raised so many questions, not only she did, did she have the courage and strength to say that to a white monster that time, which was very you know, we're talking 1880s. In that time, that period of time. And I often say this to my students, I would often say to them, you know, what do you think was the most valuable thing to Badimia people around about that time? You know. And you know, a lot of them, you know, little millennials would respond by saying,

“Awww their spirituality”, [in a mock whining voice]

things like that,

Audience:

[laughs]

Dr Carol Dowling:

No, it was actually western clothing. It was western clothing because if you didn't wear western clothing, you were shot. And the little faces would be going, Oh! So, her saying, go find one of your own come was quite a powerful thing and in context, do you realize that she saw his world, didn't like any of it, and she paid the ultimate price, which was she left her daughter with him as a servant. So, she their little daughter, Mary Oliver, at that time became his servant. And that's that painting there. See this picture there? That's my great grandmother as a little girl.

So, she's, she's working for her father. He ran an inn up there; Edward Oliver was his name. And they had an inn, and it was called “The Shadow of Death”. And it was always running out of, you know, fodder for the horses and, and, and alcohol because it was mini goldrush at the time. But I imagined, we imagined her, Julie painted. So yeah. See what I mean! This is me, I had to write a chapter about this and then she puts it in a painting that internal longing for country you see inside of everybody body. But she was a servant. She was, you know, she would… he did eventually go on one of his kind. He went off and married a young… I think it was 20 years younger than him from Dongara and they had a mess of kids. And who do you think was looking after the kids? Granny? So, she became a father's servant, literally, and looking after her own siblings, really. But ummm, one of the very first records of Granny were ummm, she got in trouble with the police because she gave too much brandy into the milk and got her half siblings, who were her charges, drunk. You know, they’d do that back then to make them go to sleep. But she got…. in my thesis, it’s her getting jailed up by the police for, you know, making her siblings drunk. But the thing is, you know, there was this, there was this real power differential. And we were constantly taught and brought up with this feeling of like, you know, how strong Melbin was to say that to him. But there was always this price, you know, this sort of I don't know if this is answering the question, but, you know, the lived experience was always about being aware of power, you know, the power differential and and trying to question it, you know,

Professor Jane Lydon:

And I think actually you've raised a really central issue for historians, which is on the one hand, how do you acknowledge the dehumanization of chattel slavery, where one person is owned by an by another on the one hand, but on the other hand, the humanity and the resistance and the, the kind of survival resilience, you know, the kind of life of people like your family who who fought back. So, sorry just to jump in there.

Professor Alistair Paterson:

Yeah. There's a great, there's is a great book on, on, on South Australia called Survival in Our Own Land. A very early kind of piece, pulling together some of those sources that really brings that home and also the language of the legislation at the time. So, you actually have the master that you talked about, the master, so the master and servant act was an attempt to kind of…. was a direct recognition in the colonial world about the nature of the work of both men, women and children in industries like pastoral industry, in the pearl industry and, and I think what's an interesting thing about the work, Julie, and just jump in, Julie, when you need to as well.

Dr Julie Dowling:

Um, you want me to start talking or…?

Audience:

[laughs]

Professor Alistair Paterson:

Yeah, go for it! please, that’d be great.

Dr Julie Dowling:

It's interesting when we talk about the word slavery, when you know, when they were doing all that stuff with Wilberforce and everything in England, they were still negotiating land and the doctrine of discovery in America. And they'd just finished a big war over there for American independence. And it really was a well, it was a land grab. No, no other word for it. The idea of slavery, though, there's a great documentary you should get. It's called “Racism the History”. And in that it describes the trajectory of Wilberforce and everything else was that anyone that wanted to not be a slave had to conform to be a Christian. So, you had the terminology wrapped into an ideology. And so, if you think there's any kind of you know, the thing about it is that you think there's no kind of strings attached. There was. And that meant that anyone that didn't conform to that idea of being Christian, that was whatever. They were still subject to the ideas of elimination. And that's why you see things like happening in places like Tasmania and Namibia. So, my idea of what slavery is, is being stuck with an ideology that you either have to defy in a rebellion or resistance or conform to it and live. So that is a slavery of ideology. And the idea of what slavery really is to me is, is having no option. You know, it's either do what I say or die. And also, that goes for the idea of indentured servitude because they had no other option. They couldn't quit, they had no option to go to another gig somewhere else, although they were moved around a lot by the missions. So, the terminology is really based in history. And the other thing when you think about it is that our mob don't regard linear time. So, when we talk about our ancestors, if we really want to talk about the truth, we still feel them with us with the stories that they've told us. So, we are constantly code switching, which is actually, actually turns up to actually give us a bit of trauma in the in turn of that. So now we're dealing with two kinds of trauma. One of them is epigenetic memory, which actually gives us a lot of these funny diseases. It actually literally is in our genetics that we don't live as long. And you can see that the closing gap. You see, the new records that are coming out and none of that's evidence of, well, we can have epigenetic memory for 17 generations. So, a lot of preventable diseases or strange things happening in our genetics that gives us like a double double whammy of trauma in our and our response to basic things that we, you know, people that have never had to go through things like massacres to deal with. So, if we ever go for…. I’m sort of talking too much but….

Professor Alistair Paterson:

that’s alright.

Dr Julie Dowling:

If you, if we really look at like going for compensation for slavery, it would really be a good thing to go towards because it helps us live longer. Just the basic’s you know. And it's interesting when you talk about the Caribbean, because a lot of their mob are going for like compensation for slavery and then terms that are based on healthy, healthy outcomes and every now and again, I sort of think a lot of that was based on an incredible kind of aggressive narcissism, meaning that they had a network of codes that you had to comply to in order to be, quote unquote, civilized. But then they, they, they started that with the noble savage, right, which I'm reading about at the moment. And the noble savage….

Dr Carol Dowling:

You told me you were going to talk much tonight.

Audience:

[laughs]

Dr Julie Dowling:

Sorry. So, the noble Savage was one of the big things when it hits W.A. Yeah, because they had an engagement already over east and did a lot of dancing with each other, which is great. But when they got here, it was sort of like the noble savage was very romanticized, and then somehow some Scottish guy took it off the hands of Rousseau and turned it into something else. And his name was Crawfurd, it’s a weird guy's name. So, a lot of my research goes into the emotions that can go into paintings because then I'll be able to translate these literature parts and trajectory of history into these images, which also relate to the language of my mob. So that's it. That's all I want to say,

Dr Carol Dowling:

No, it ain’t.

Professor Alistair Paterson

We're going to, we're going to get to some of your paintings as well in the next section as well. Julie So…

Dr Julie Dowling:

Alright ok, yeah,

Professor Alistair Paterson:

I wouldn't mind just kind of just staying in the deeper colonial past because, you know, one of the things that everyone here and other historians are revealing are all these new understandings of the past, and particularly the work that I know that, for instance, I refer to your project before, Jane. The thing that I found really surprising about that we're sticking a little bit with slavery here of the ways in which Australia was connected to those bigger global stories of, of slavery. Can we just go global just for a few minutes? And then before we we come back to, to Western Australia and explain how those discoveries, I think, of what your project has done, how they relevant to, to Western Australia.

Professor Jane Lydon:

Yeah. So, thank you so very relevant. I think I've mentioned that slavery was abolished in the British Empire or most of it. Not if not all of it, not Sri Lanka, not the East India company properties and so on, but most of it in 1833. So, when you think about it, W.A. was established in 1829, 1830, so that was four or five years before slavery was abolished. And so, if you go even further back to the establishment of the Australian colonies. You know, New South Wales was invaded in 1788 by the British. Slavery was in full swing. Britain was the world's leading slave trading empire at that point. So that's 50 years where the slavery system overlaps with colonization in the Australasian colony. So that's really quiet an interesting conceptual shift for many of us. It's only recently that we've really begun to ask that question. Well, what does that mean? And I think in a big picture sense, to answer your question now, that means that as Britain was debating the end of slavery and many, many people argued more and more strongly that they had to outlaw slavery at the same time, the slave owners were looking around and thinking, well, we're going to lose money here and they were putting up a fight. And so, over the decades, you know, as we get up to that kind of turning point of 1833, supposed turning point, they were saying, well, you know, what can we do to replace that that loss, that loss of our property and that, of course, is when during the 1820s we see them start to turn towards the Australasian colonies. So, during the 1820s, instead of saying, okay, they're just a convict dumping ground, they're starting to say, alright, there are opportunities here for new forms of exploitation, new ways to make money, and that's where the colonies, the settler colonies became the answer. So, I think that's really how we should be seeing that that global history. It's one of the movements from the first empire, the so-called Caribbean colonies, to the second empire, which is the so-called settler revolution.

So, in a way we can see that…. And I'll just, just very briefly make a couple of points, big project based at UCL, in University College London published a database online in 2013 where slavery compensation that was paid to the former slave owners, not the enslaved, but the slave owners was paid in 1833. And we have a record. So that was all recorded in Hansard and that was put into a database which went online in 2013. So, you can go to that date database and type in your own family's name or any family name and find out whether they were awarded compensation at that time. By the way, that that compensation was paid by a huge loan worth billions of pounds that was only paid off in 2015 by the British government. It's quite mind blowing.

So, what our project has done is to say as a starting point that compensation money, can we follow the money trail? Where did that money go? We know that two hundred and thirty hits in that database ended up coming to Australia, two hundred and thirty claims. And of those anyway, I can talk more about that later, but that is really the link and the starting point for us. So, by following the movement of people and money and the investment in the Australian colonies, just think about what came with those people in the money. It was practices, it was practices of incarceration and violent punishment. And by the way, that term punishment really implies that there was something legal that people had done, had breached, you know they had done something wrong in order to be to have this kind of physical torture inflicted on them. And these are things that we know were being brought from the Caribbean slave colonies out to the Australian colonies. So that's a bit of a long answer to your question.

Professor Alistair Paterson:

Yeah, I think it's astounding some of that work, though, the way it kind of gets us to revisit these places. Julie

Dr Julie Dowling:

Um, I just sort of think in terms of, of what happened to grassroots mob across WA. I mean, when anyone committed a crime, no matter how small it was, right up until the late, late fifties. Right. They had to, if they had to present themselves in court, they had to do it in chains, even a serial killer, right, didn't have to do that. So, if you see that, then you always think that, well, there must be a general kind of fear of us resisting in any way, even if the crimes might have been small. So, there was a real kind of, I don't know, a paranoia based on, you know, these kinds of rebellion. And I mean, people talk about Daisy Bates as one of those people that brought that into the realm of the newspapers for the first time, saying things like we were cannibals and that, you know, that we would start rebellion with the Irish. That was another strange sort of thing that happened in WA at the point of, you know, when WA was going to secede from the rest at some point, which was around about, I don't know, 1900 or something, and they were really looking at the fact that how were they going to keep this colonial state together and they saw indigenous people, First Nation people was a problem If they hadn't already, you know. So, we seemed to be like we've always been scapegoated, you know, and in a sense, unless we comply. And and the thing about that is internationally, we've, we've actually found a better way internationally to be recognized for who we are. It just happens that, you know, it's very different to try and translate that with so much media involved and that was right back in the early days of newspaper too. So, you know, it's a very powerful thing, newspapers. I mean, when John first came through our country, the first thing he said in a newspaper was flippantly that all these Badimia people are cannibals and yet, there's no scientific evidence of that. There's no historical record. It's not in our culture, nothing. So, they went for it anyway and what that caused is a ricochet effect to anyone that was looking for gold and then just come through and, you know, treated our mob like vermin, basically. And that's recorded, isn't it? So, you know what I mean. You had that, uh, what was it, the preacher, what was his name, Gribble! Who came through and, and said,

“Look, this is wrong. You can't treat these people like that.”

You know what I mean? I read all the accounts….

Dr Carol Dowling:

Yeah, yeah. Gribble…. Gribble is, you know, sent ripples.

Dr Julie Dowling:

Yeah

Dr Carol Dowling:

Gribble sent ribbles. Anyway, I quoted Gribble quite a bit because of the way that he gave account of what actually happens up and particularly up in places like Cossack, you know, which was the pearling town. The pearling centre, it wasn't Broome, it was Cossack. And we know from Badimia story is that our mob were men, women and children were walked from Badimia country to Cossack and chucked off boats. You know, they also, particularly at a cruel way of thinking that pregnant women were better to be chucked off these boats because they had less lung capacity.

Professor Alistair Paterson:

This is as divers, you're talking…

Dr Carol Dowling:

As divers of these, these pearling boats. The other thing, too, is we cannot underestimate the significance of Rottnest Island. When you list you see the list of what these mob were actually charged with and where they were from. Usually they were showing, um, resistance, you know, and often they were in there for like stealing a sheep, stealing a bullock, you know. So, they're really trying to get our men controlled, our men away from any position of proper retaliation. And what was left was our women. And in fact, that's what I found in my thesis was that, you know, what role could women play?

They're very vulnerable in that, in our, in our, in our country, because there was no law up there. You know, there was no checks and balances by any anyone in this squattocracy. We called it. It really was a bunch of squatters up there taking however many Badimia wives they wanted, producing however many Badimia children they wanted, and, um, you know, we didn't really actually see real, um, freedom or not really freedom. What's the word?

Dr Julie Dowling:

Well.

Dr Carol Dowling:

There was no change until white women went up there because…

Dr Julie Dowling:

Well… [inaudible due to Dr Carol Dowling speaking over the top]

Dr Carol Dowling:

They looked around and saw kids that were for are products of those unions and so if they wanted to be a part of the establishment in Perth, these people that had established vast areas of country, I know in particular Edward Oliver and his brothers as well as Francis Latham, who married Granny were became exceedingly wealthy on the back of female Badimia labour. Because you could plop them out in the middle of nowhere to, to, to be self-sufficient anyway, because they could eat bush tucker or their family would feed them, their family would come and feed them. But they would be able to tend through thousands of heads of sheep. So much so that day, I think it was Francis Latham, had three hundred thousand hectares of land. This is my, my, who married my, my great great grandmother. And they had nine kids together.

Dr Julie Dowling:

Yeah. And he married her.… [Cut off by Dr Carol Dowling]

Dr Carol Dowling:

And while she was still pregnant or whatever. She was droving sheep for him, you know, making him exceedingly wealthy.

Dr Julie Dowling:

He was reluctantly married to her at the, by the policeman at the Coorow siding, you know, railway siding, because the local constabulary figured out that she wasn’t married to him.

And another thing… [cutoff by Dr Carol Dowling]

Dr Carol Dowling:

And there were weird things that happened. Weird stories. Like, for example, one of the things I found in the research was that there was a reverend that would go on the train, literally on the train, all the way up through, you know, Wubin, Latham, all the way up there. And he would marry these white men to the aboriginal women.

This was around about 1906, because the 1905 act came out, which was a horrible, all controlling legislation that really, I think, targeted women. You know, the 1905 Act. And this guy was marrying, you know, these white men to Aboriginal women because, you know, they didn't, you know, these white men didn't want their kids taken off them.

So, Frances Latham ah, who married Granny, they already had five kids when they got married on the siding, in Coorow and then he jumped back on the train this, this reverend and went on to the next one and married more. You know, it was like there was like this sort of tidying up of, you know, of, of the morals or something going on up there. You know, it was very strange.

Professor Alistair Paterson:

Can we, can we just talk a little bit about kind of evidence around these periods of time? Because, you know, as Jane mentioned and you've alluded to, there were these vast networks of incarceration, whether it's chains or places like Wadjemup or Roebourne jail or, you know, a boab tree in Derby, or these networks. And then we have the police and police records and equally we have the newspapers and, you know, the terms that we're using here tonight, um, are actually turning up in newspapers. I'm sure we have quite a few historians or amateur historians, um, here in our audience who might use, you know, sources like Trove. Where you can now go and actually, you know, look up these key words and suddenly, you know, all of these experiences which come pouring out of the newspaper. So, these are words that are actually used, you know, throughout history as well. So, it's actually a really interesting time to kind of delve into those histories. But, you know, how do… in terms of… how do you all find your way through to the past? Is it just through oral histories and talking to people, Carol, for your PhD…

Dr Carol Dowling:

No

Professor Alistair Paterson:

Or for your work Julie, how’s it done?

Dr Carol Dowling:

No. Well, you know, there's academic rigor, isn't there?

Audience:

[laughs]

Dr Julie Dowling:

Yeah, but I don’t have to deal with that.

Professor Alistair Paterson:

We like academic rigour.

Audience:

[laughs]

Dr Carol Dowling:

We like academic rigor and anecdotal evidence is not appreciated. So, you know, it's trying to in some way trying to make our lives, our reality, our strength of oral histories fit within the, within the academic environment. So, so, yeah, I, I went and did the search. I thought, how am I going to handle this? You know, you know, I, I needed to. So, I wrote a chapter for each woman. So, I wrote a chapter about Jules and who, who she was as a person. And then I've moved right back to Melbourne, what was happening with her and then granny, and then and, my nana and then my mum and, and every which way, you know, it all actually does have this thread of slavery or, you know, indentured labour. It was all riddled in my thesis. It was just, you know, um, one of, one of the, one of the most powerful things I've found with, um, the story of, um, my grandmother is how well the squattocracy, even in the thirties, had it all stitched up with the Catholic Church. We were having a yarn about it just before, about how you could lay £50 down to the Catholic Church and say, is my little daughter here who has an Aboriginal mum.

You can have her, and you know, she, she, um, can be educated or you know, um, kept away from marrying the town blacks because that's what happened to Granny and Aunty Dot, um, to Nanna and Aunty Dot, my Nana. And when it came for me, the granddaughter to come in there and try and find out what happened to her while she was in St Joseph's Orphanage, they said.

“Ahh, nah, nah, you can't access any material. The only thing we will tell you is what we agreed with her father was that you can see the registration when she got there and a baptism.”

No record from the time she was twelve until she was twenty-one. The fact that she worked in the laundry the whole time for the Catholic Church. No record of her health or education, nothing. Not a damn thing. And we know from family and our own experiences it was traumatic. You know, when I came to interview my, my grandmother about being separated from my mum at twelve, which is to us, that's, that's, she's a woman. She's a woman there. She's very conscious of herself as a Badimia person at that age, and probably speaking fluent Badimia, that it would have been an extremely traumatic experience. And, and in my research I had to I had to not just, I had to just forget about that brick wall and look at the documents that were written about these triumphant white men who were my ancestors and Trove, and I found many newspaper articles about the local police going to Francis Latham and how he was abusing her, granny, and and weird things like their divorce event, where the judge literally said to Francis Latham,

“She couldn't be a wanderer”.

You know, he was claiming that she was wandering around everywhere and, you know, she would never, you know, stay at home and stuff like that. And the judge said to him,

“Well, she couldn't have wandered too far, you had nine kids with her”,

you know. So, there was, there was this a fascinating juxtaposition of, of that, native welfare records, which we got that were just so brutal about the way that they spoke about the women in our family and, and, and they were even questioning Francis Latham if he was a black fella because he was too concerned about his kids and the orphanage. You know, that was thinking, I must be a blackfella. Yeah. So, they investigated right back to the local cop to find out, you know, it was just so many bizarre twists.

Dr Julie Dowling:

[inaudible due to mic distortion] …. there’s a whole kind of, um, like a real kind of religious paranoia that it's, it went from we were related too closely to demons, right, because the colour our skin and then somewhere it got demonized into us being somehow communists. And even now they still think we're communists because people like Karl Marx and Engels and all that referred to us as primitive communists. But we're not. We believe in a single creator. A lot of us, you know, can't understand why we get relegated as that. I mean, that's the reason why in reconciliation that they used to called Fred Chaney, “Red Fred”, because they thought that he was dealing with a bunch of communists. So, you see, there's still that sort of stigma going on, and it's really led by newspaper and stuff. But I had to, when I was doing research, a lot of my stuff was look at these…. When I when I actually got out of high school and we were basically probably the only the second person apart from Aunty Liz, I think, who graduated out of high school. Um. It was the same time that we got the Freedom of Information Act in 1986, which was begun by a guy named Ralph Nader, who viewed that information was not necessarily power, but it also represented peace and he was right because it's a part of the United Nations to talk about peace, is that you have the right to find out who you are. So, we went back into these institutions to look literally for family. So, a lot of the photographs, like the one in the picture that's there at the museum is of unknown people. So, what I did was get those pictures and find out who they were by happenstance, maybe. Hopefully this nation family will come across it and say, that's my auntie or uncle or whatever.

Dr Carol Dowling.

It's happened many times, by the way.

Professor Alistair Paterson:

Well, you’ve, you’ve just jumped, you've just... Julia have just jumped to exactly where I wanted to take the next part of the conversation.

Dr Julie Dowling:

Oh, right right…

Professor Alistair Paterson:

So, um….

Dr Julie Dowling:

Well well, I’ll tell you one last thing I found too is that, there was kind of, um, there was a lot of, there was an element of it which was based on opportunistic kind of organized crime against First Nation people because it was a rationale of exter, exterminating religious practices for a start and I can describe that by looking at A.O.Neville's alias list. He has a list of alias people, and I tracked this one fella who was obviously a journeyman, like, well, an Iritja like, a a person that was engaged in sending messages across songlines and they tracked him and then somewhere along the line, someone cut his leg off. Some wadjella got him and stopped him from walking. So, he travelled, used to travel from the coast into Badimia country and beyond and that was really what our commerce and our, and our, um, our…the people used to leg it basically. Like all the early kind of, um, roads, they were actually our mob sending messages between each other. That was our that was our government rationale was to send messages. And there's a famous, um, you know, there's a famous kind of well, um, ah, well at least for our mob anyway, grassroots about how the colonials had never gone up to one of the earlier tracks and was actually following this track with the horses and stuff and an Iritja ran past them in full gear, like, traditional gear, and didn't even look up at them. He was too busy in the task of getting a message to somewhere else, and then they, they, they freaked out because they’d never saw a, that kind of thing going on. But when the next one came along, they shot him, and then looked in his bags and everything else. So, we had a very active, polit, political system in our countries and that still goes on now. We use, we use the back of our cars to send trade and then people sort of think about us having, you know, position in the Australian state or whatever. But we have a different sort of government going on at the same time and our grassroots systems are very solid, thank you very much. So, what I've pained about is trying to get the information out there that we still have systems that need to be respected as well as, you know, negotiate things like, you know, a history that shared and not one that's based on like, you know, them trying to cause themselves self-harm by saying that, you know, that these things don't exist or

don't, didn't exist. Because when you deny history, you deny your own freedom. That's basically it. I mean, if you look at South Africa, they've already figured it out. And other countries all over the world. So, when you look at that stuff, you're actually saying, I'm not going to do that anymore. Yeah. Okay. Sorry. Off my soapbox. Yeah.

Sorry, we, me and Carol argue all the time.

Dr Carol Dowling:

You have no idea.

Dr Julie Dowling:

Yeah, yeah. No idea [laughs]

Dr Carol Dowling:

Yeah, Jules and I live together, so I'm her long suffering, unpaid art assistant.

Professor Alistair Paterson:

We could have put two TV screens up here and had you argued against each other.

Audience:

[laugh]

Dr Carol Dowling:

Would have been an art installation.

Audience and Dr Julie Dowling:

[laugh]

Dr Carol Dowling:

The, the thing is, we. You know, the story is so important to our family. The only reason why I wrote my thesis was for my family. Um, and, and also, I was competing against Julie because she already had a PhD and I had to get one.

Dr Julie Dowling and Audience:

[laugh]

Dr Carol Dowling:

But it took me a long time. But I finally got it, and we made the, our mom proud. So yeah, it was fair. The thing is that, you know, when you, when you think about the processes of representation, it becomes really important for our mob. Julies has always been about trying to, to let people delve deeper. It's not just the superficial, you know, you might. She messes with people's head all the time and she'll correct me with this anyway. But, you know, Julie uses lot of glitter and sort of…. but it's not, it's not expensive stuff. It's really, it's really trying to create a painting that really entice the viewer, the, the eye. So, you [inaudible as Dr Julie Dowling speaks at the same time] pretty, pretty, pretty, pretty and then you realize all holy shit it’s about colonialism, you know? So, the paintings are really powerful.

Dr Julie Dowling:

A lot of a lot of my family are sight impaired because of, you know, we've got different issues with sight because didn't have really good diets growing up and stuff. So, I like it when they're shiny and my mob can look at them and feel them as well. So, it is an intrinsic kind of, um, you know, it connects people to the story. But, you know, my family can get the materials as well.

Dr Carol Dowling:

So now we'll just let Alister do his job.

Professor Alistair Paterson:

No, no. Well, I'm just I mean, well, we’re already talking about, I wanted to leave words behind and think about images, and we're now talking about your art, Julie. So maybe, could you just talk a bit more about the process? I think about how, you know, you said you encountered some images and you decided to respond to them. How does it…. how do you respond to, I guess, a historical record and then bring your art into creation and maybe you go through the method a little bit more?

Dr Julie Dowling

Well, my family are trackers and it's a part of our role. We used to send messages, like I said before. So, we used to have a message track that used to go from Badimia country right down through to Nyoongar country down to Pinjarra. So, we used to travel to Bruce Rock, across Maddington, down to Matagarup, which is like Hindmarsh or whatever they call it island, you know.

Dr Carol Dowling:

Um,

Dr Julie Dowling:

…. You know the one….

Dr Carol Dowling:

Heirisson, Heirisson Island

Dr Julie Dowling:

Yeah, and then travel down to try goods and information down south. So so, when I do that, like I know that, right, I also do that with images. Sometimes I'll find one and then there'll be an image there. I'll say, “Hang on a minute, this is something that is too familiar or not familiar, but it's a part of… it's like either a… it's not necessarily a roadblock, but it demands kind of a reflection. So, when I look at that picture of those two women, I sort of realize that my family is… not only used to do that, but I used to do that. And I mean, my family grew up really poor. So, there's, there's like sort of bits about that where I also heard that you can come across women that have got like internalised misogyny about women and that they'll work for people, um, to, you know, make women feel less empowered to have even a voice. And that's the term for that is carrying water. [laughs]. You know, like carrying water for misogynists. And then I was looking at that picture and I thought they're not doing that [laughs]. You know, these people, these, these women probably were taken there very young. And the image itself starts talking about, well, how come I don't know where that where that is?

And so, they've become sort of like…. you know, um, you’d like to think that this family out there might know it. So that's becomes sort of like a, like a language and trade currency to find them. So…. I don't know. Sorry, I'm an artist, I never stop.

Dr Carol Dowling:

She rambles. You have no idea.

Audience and Dr Julie Dowling:

[laughs]

Dr Carol Dowling:

It's great, though, because, you know, you sit there and all of a sudden, she's producing an exhibition.

She has an exhibition on right now in the, in uhhh.

Professor Alistair Paterson:

Niagara

Dr Carol Dowling:

Niagara galleries, in, uhh, Melbourne, Richmond. So, she's done fifteen works that are based about Badimia country, but it's actually a celebration about our mum because, umm, we're still in sorry business. We lost Mum last year in August to motor neuron disease and, umm, but when she passed, goddammit her twinnies had both PhD’s. She raised us up, single parent and on welfare. She’s the bomb.

Audience:

[applause]

Dr Carol Dowling:

Yeah, very, very strong storyteller our mum and so she. she made granny story alive to us like we almost she died before we were born, but we knew, we… it was like was alive to us. And when it came for me to go back to do my, my thesis on country and being connected with family there, the things she told us about were there, you know, it was such a powerful process.

Professor Alistair Paterson:

I've got a question for Jane, who's done a lot of work on historical photography of and by Aboriginal people and written about it. How much do you see, um, people, how, how… the different ways in which people have responded to me guess some of the ways that, you know, those historical images of Aboriginal people that you've encountered.

Dr Jane Lydon:

Yeah, yeah. Great question and just listening to Julie talk about her work, I think there's something about all images that is very powerful and accessible and kind of concrete. And I, I, I was at a conference when some people were talking about colonialism and, you know, people were feeling quite upset, I think, and then we started talking about art and showing art and in fact…. Tasmanian Aboriginal artist Julie Gough was there, and she sort of said, she said, I think art just….

Dr Julie Dowling:

I went to Uni with her.

Dr Jane Lydon:

But? you did? Yeah? So, she said….

Dr Carol Dowling:

They went to Uni together.

Dr Julie Dowling:

It was the same year, we went together, [inaudible as Dr Carol Dowling speaks over the top]

Dr Carol Dowling:

The two Julies.

Dr Jane Lydon:

Ahuh,

Dr Julie Dowling

[inaudible continued from the previous entry] … major and I was doing painting.

Dr Jane Lydon:

Ah, ok, so, so you probably know, you've probably heard her say it, but she said,

“I think art does something to help us emotionally engage with these questions and move on in a more, you know, we can communicate through art and images.”

So, to answer your question about historical photographs, which is what I've focused on in my work, I think there's something very satisfying about images, photographs of the past, because they have that sense of weight and authority. You know, they show us something that really was there, but at the same time as images, they're accessible and everyone can engage with them and form their own views and interpretation. Even though we know that images and visual meaning are often, you know, that meaning is shaped by words or context or a caption. So, so your question is, you know, what do images do? I think they really allow us to engage with the past in those ways.

Professor Alistair Paterson:

I mean, that really sort of truth telling.

Dr Carol Dowling:

[Tries to speak but Professor Alistair Paterson continues]

Professor Alistair Paterson

Sorry, I just did that to you. Sorry, I’ll hand over to you.

Dr Carol Dowling:

You're right.

Professor Alistair Paterson:

You go.

Dr Carol Dowling:

Um, so there I was up in Badimia country and, ahh, you know. I went to a place called Ninghan because we'd heard Ninghan station. Ahhh you guys probably wouldn’t know Ninghan, Ninghan station. It’s run by, it’s a, it's actually an Indigenous protected area now, has massive biodiversity there and it's run by Badi, Badmia people, and I know the family very well, um, Leah and Don Bell and their son, umm, Ashley. Who's… we've served, served on a board together. But, um, biscuit tins, you know, when they pull the biscuit tins out and they're full of photos. And one day she said, “I know exactly who you're talking about”. So, she came, and I was sitting there and, um, she opened the tin and there was a picture of, this one particular photo of this…. Um, you could tell something was powerful going on this picture because it was a little tiny little Badimia woman in the front, and she's holding a wana, which is a digging stick. She's holding it right there. And behind her is a whole group of other Badimia people, and particularly this very tall woman that I recognized immediately as being from the Galbraith assembly.

And I knew exactly who she was because five of her daughters married, five of my nannas’ brothers. And that's proper ways, Badimia ways. They, you know, some of them stuck together, some didn't. But when she said to me, that woman in the middle there is a lady called Shepherd Dinah, and I went, oh my goodness. See, back in the day they were they were called Shepherd, you know, because that's what they did. They didn't have a real name. It was called Shepherd. So, her name was Shepherd Dinah. And at that time our Nanna was still alive, and she was, she was bedridden at this time, and I took the photo to show it to her and straightaway she pointed to it and said that old girl birthed me. And I'm like, straightaway, my whole perception of my great grandmother giving birth to my nanna. Umm, I thought she did it alone. I thought she went out there with a knife and a horse and dog went out there and birth the baby herself. No, it was, she was tended to by Badimia women, and all of my nanna and her siblings were all born proper ways in the bush. But because of that photo, it brought back so much power because, you know, when she said that, my nana said that she said that old girl birthed me. She spoke as a Badimia woman, you know, not as a woman that went to an orphanage. You know, very powerful.

Professor Alistair Paterson:

Umm, Can I, you go Jane. And then I'm going to go open it to the floor.

Dr Jane Lydon:

I just had to say thank you for that fabulous story. And in fact, quite often, I mean, I think this is really the great outcome of working with photographs like this in the wake of the Stolen Generations, when so many families have been fragmented and lost relatives. The photographs over and over again become this fantastic link where people find their family again. So, yeah, just want to say thank you.

Dr Julie Dowling:

I mean, can I just add a bit in there? Because when we got the Freedom of Information Act through, which was international, really, it was a, it was actually trying to give people the right to look at the records, everybody. And we, we thought, well, my family were courageous during World War Two and all these other things that had to pick up some courage and go in and look for family. But there was a kind of a sad stigma about these images because when mob use to get lined up anywhere, then someone would go missing based on the colour of their skin, or if they were old enough to get worked on them, that was sent away. So, there was a stigma to these images. So, we went in there and thought, Right, well, how can we, how can we take a negative into a positive? So, we look for family members and say, do you know where this person went? And we literally became like private investigators or, in a sense that we were looking at it in terms of empowerment. So, these images, these images have currency in as much as a healing process. And our mob in Badimia, that's what our country is. It's like a hospital, it’s like healing.

So, you know…

Professor Alistair Paterson:

Can I…

Dr Julie Dowling:

...when we look at, we look at the images, but we also have connected to… we actually are trying to track the family again and you just got to find people that are generous enough to help you find them. So, and we're still missing family so… yeah. I just sort of wanted to say it like that.

Professor Alistair Paterson:

I'm going to open up to the floor, because of this. I'm sure there might be someone who has a question they want to ask of our panel. Yes, here in… you just have to speak up. Oh…

Dr Carol Dowling:

We got a mic coming.

Professor Alistair Paterson:

We have a roving mic. You don't think you need it, but you do. Oh, no, there's one. We’ll do you and then you. It's all right. Thank you.

Audience Member 1:

Hello. Sorry, I'm just earlier on.You were talking about slavery. I think my brother had a question about slavery. And with us, it was the Stolen Generation. She said something about that, what was it? You said something about slavery and Stolen Generations in England. Was it in England? Where the slave owners or whatever got compensated it?

Dr Carol Dowling:

Um,

Dr Jane Lydon:

Yes.

Audience Member 1:

Here it's Stolen Generations compensation. And ah, also a little bit about, um, I don't know if we could go for slavery compensation, but I'm just a little bit about my mum, who's Badimia.I grew up thinking I was Nyoongar Whadjuk [chuckles], but I've had a lot of people telling me, you don't look Nyoongar Whadjuk, you look like Yamatji [chuckles] And so when I look at my background it is, we are more Yamatji than Nyoongar Whadjuk. This is what the putting the children in the missions did because my mum was put in a mission when she was very young. That was Roland's mission. But before Roland's mission there were in New Norcia and at the time, they were told the government, A.O. Neville said that the parents shouldn't have a home and they didn't have a job, so they couldn't have their children. And then when I did get a home and they did get a job, they still weren't allowed to get their children back because the children were being taught to become slaves, to become servants, sorry, servants to the station owners. And so, children were sent from the mission to the stations like up north. And my mum was one of those.

Dr Carol Dowling:

and they looked after their wages, which they were going to give them, their wages eventually.

Dr Julie Dowling:

Yeah right.

Professor Alistair Paterson:

Jane, did you want to say something specifically about the compensation issue.

Dr Julie Dowling:

Um, we got family members, right?...

Dr Carol Dowling:

Hold on Jules, someone’s talking.

Dr Julie Dowling:

Sorry,

Professor Alistair Paterson:

Yeah, we’ll come… Jane and then, and then Julia, if we can.

Dr Jane Lydon:

Oh look, I mean, I think that's a really good point you've made because that's exactly what happened. They, you know, they, these children were taken from their families, and they became a source of labour. And so, a lot of, actually, there are a number of historians now working on histories of domestic servitude. You know. So, if anyone's interested very well come to get in touch with me. But that's exactly what it was. And the same techniques that we've seen in many times and places were applied to keep them in one place. They couldn't leave. They had no control over the out, you know, the outcome of their labour and, their so-called wages and so on and so on. And I think Julie and Carol have been talking about exactly that experience tonight.

Professor Alistair Paterson:

We've got a question here in the front row.

Audience member 2:

Thank you so much to everyone for sharing their stories. It's been incredible. Um, Carol, I had a question for you.

Dr Carol Dowling:

I don’t know, I don't know anything.

Dr’s Carol and Julie Dowling:

[laugh]

Audience member 2:

I was just wondering about your experience in the writing work that you do, and I guess writing in the colonizers language and then also writing about, I guess, nonlinear understandings of time in the, you know, I guess in a way that people or, you know, we now know…. Westerners see as linear if that, you know, do you translate it how do you work with that?

Dr Carol Dowling:

Oh, it was hell, it was hell. I think the first thing that was really worrying for me was losing the richness of oral history into the written word. How finite it becomes. And I come that across with a lot of other First Nations writers that how can you, you know, how can you be so arrogant to think that you can write this stuff? That's the feeling I always felt when I was writing it. Because when you're little from a little age, up, going older and it gets to the point where you're actually able to recount these stories yourself. you often have the old…. like always had mum there or someone else would all be yarning, and they would correct me and say, “No, no, no, it wasn't really like that.”

And then, but they still be very patient about me being able to make it my own story and then being able to put that into writing became a really difficult process. But because of, um, the field of autoethnography, I don't know if you guys are aware of it, but autoethnography is auto, you, ethnography, a culture. So, you are within the culture writing about it. And the analogy I always use is like, you know, imagine for, for dec, for centuries anthropology has been used as a tool of colonialism. So, it was is all based on this idea of cultures in a petri dish. So, you they're going poke, poke, you know, but when you're doing autoethnography, you're in the petri dish. And not only that, you're trying to smash the petri dish. So there's not just, it's not just writing. It's a, it's actually a political act, act as you're doing it. And the worst thing about it is, as a writer, because I do, I've done many forms of writing, not just some academic writing, but writing for radio and all these sort of, you know, script write, all this sort of stuff.

But to, autoethnography demands that you do poetry, demands you do prose. So, when you're going through, like the experience of learning about your history, the process of learning about your history in various forms and on uncovering stuff, Autoethnography demands that you say, well, how the hell do I feel about this? Because you have to. How can you how can you be devoid of emotion when you find out…. Like I remember once I found that Badimia people were taken to the Greenough historical site. Greenough is now and old…. you can go there and literally go to Greenough Township there. It’s an old historical site. And I found in my research that my one of my ancestors, my white ancestors, was a jailer there. And then I also found out that my, some of my Badimia ancestors, some men were taken there.

So, there I'm standing in the middle of the actual jail, realizing and looking in to, because when you go to the Greenough jail that you've got, you see the individual prison cells that they've got holding cells for the white prisoners. And then they have the ones of the the black prisoners, which is literally straw on the floor of an iron bar on the wall where they used to chain them by the neck. And then I'm standing there realizing I'm actually a product of the jailer and the inmate. So, I had to write about it. I had to have, how could I not? And then there was other incidents where, you know, I was just, I was just trying to make sense of what it must have felt like for Melbin to be taken to be taken to England from the desert, because our mob was desert people, semi-desert. to go on a steamship, because at that time steamships were so new to Perth that we were sending things so much quicker to and from, from England. So, it was more likely that, you know, that, that, that, you know, a trophy of the colonial conquest, a.k.my apical ancestor was was taken back to England because they were doing it to so many other indigenous people from all over the world. You know, it was the Time of the World exhibition, you know, in Paris. So, they had gentlemen's clubs and conversation parties where they had, you know, indigenous people from all over the world being photographed and poked and prodded and and the same with exotic animals. So, we were exotic.

So, but at that time was so powerful at that time, is that's when whiteness became a concept. That there was the the colonized other. They had it, they were able to create a sense of themselves. And then knowing that, you know, she was gonna, she was leaving country and probably never coming back. And to actually imagine what it was like for her to look over the side of that boat and that limitless water, you know, a Badimia woman going all that way, you know. Um, and then, and then finding the ship's manifesto in my research of Edward Oliver, coming back. They recorded him coming back and in the ship's hold, they recorded twenty-seven natives, twenty-seven coming back. How the hell did they get there? You know, like, you know, and then reading and thinking, how do I process this as a, as a First Nations person today? But it's evidence, goddammit! It's proved it happened. He did come back, and she was in that hold. She was one of the twenty-seven. But I bet you she was thinking, I'm going to ditch this guy. I’m not having him in my life anymore. So yeah.

Dr Jane Lydon:

And I just wanted to jump in there because you mentioned evidence. I wanted to just give Alistair, your research a bit of a shout out because as a historical archaeologist, you've investigated these sites of pearling and found evidence for people being abandoned on islands, that’s their labour source.

So, I think, you know, we're seeing this ethnographic approach really yielding fruit because you've got the documents, and the archives and the images and, the oral histories and this archaeological evidence.

Dr Julie Dowling:

I've done paintings of those, of the pearling industry, about four of them.

Professor Alistair Paterson:

Yes, I’ve seen those.

Dr Julie Dowling:

I know because I've got a great uncle that lived up there and he's got a big mob of descendants all there.

And his name was Arthur and, umm. I've done, you know, everything from when they first brought in the Malay mob and there was a lot more concern about their welfare and how that might project out to the world as well because they were dealing with Malay subjects. It's interesting like, each boat was their own, was like an own, their own island. Every boat had a different...

Professor Alistair Paterson:

Culture.

Dr Julie Dowling:

Culture, yeah, and a different way of handling the situation very much like the Pirates, sort of, buccaneer type like,

Dr Carol Dowling:

Let Alistair talk now, he’s the one that’s done the research.

Professor Alistair Paterson:

Oh, no no, I’m here to let you guys talk tonight. Um so do we have any more questions from…. We've got one more here helping us decode all these things.

Dr Carol Dowling:

That was a deflection away from your stuff then that we’re seeing. You’re very very impressive.

Professor Alistair Paterson:

I'm trying, you know, my family tell me I mansplain far too often, so this is an opportunity tonight for me to park it.

Dr Carol Dowling:

Oh, do you? [laughs]

Audience member 3:

So, Julie does these beautiful artworks that are in the public world. And Carol, you've written your story with the memoir of the five generations. Would you consider putting that into the public world?

Dr Carol Dowling:

Oh my god, yes. [laughs] Yeah, no, people have said to me that I've got to write, um, make each chapter a book, actually, because the, it's riveting! I mean, even, you know, and the weirdest thing is they, they actually said the people who have actually written it, Julie's actually only written one, read one chapter of my thesis. But, you know, I'm not sore about that.

Dr Julie Dowling:

Nah I’ve read it all.

Audience:

[laughs]

Dr Carol Dowling:

Um, she knows though, all the machinations of that stupid… anyway it took so long.

Dr Julie Dowling:

[inaudible as she was talking at the same time as Dr Carol Dowling]

Dr Carol Dowling

But they said the best chapter was the one about my mum. And yes, because she was a child of the sixties, she was a surfer. She managed a rock band, but she was the one in our family that witnessed the breakdown of Badimia lore and language being passed on. So, she saw her mother and grandmother arguing together as to the benefit of learning Badimia culture and, you know, being able to actually hear my mother's voices, it was it was a very powerful process.

Dr Julie Dowling:

That was during the fifties.

Dr Carol Dowling:

Yeah. Yeah. But, you know, the main thing for, for, for writing, though, is it's not the only thing I do. I'm actually a radio producer as well, so I sort of like won couple national awards. Here’s Aunty Liz, oh gosh! Yes

Aunty Liz:

Is, is it true...

Dr Carol Dowling:

It’s my Aunty Liz people.

Dr Julie Dowling:

Our Aunty Liz.

Aunty Liz:

Is it true that you taught Narelda Jacobs everything she knows?

Dr Carol Dowling

Yes, I did, yes, I did. And she was very nervous.

Professor Alistair Paterson:

But it's probably good to finish off with, with a, on such a heavy topic with some laughter I think, and I said we'd go to. We've got one more… maybe we'll just do one more question and then I think I've, I'm over my allotted time so Okay go for it.

[extended silence on the recording for several seconds]

Professor Alistair Paterson:

Did you hear that, Julie?

Dr Julie Dowling:

No,

Professor Alistair Paterson:

the question was really how do you reconcile all your ancestors, both white and Aboriginal in your art or do you? Is that a theme that comes through your own story?

Dr Julie Dowling:

Oh, that's an interesting one. Umm, I well, art is language, and I suppose I try not to code switch in my language too much, but I am a Badimia woman. I'm not Irish, I'm not whatever anything came into it. As much as I love my grandfather, who was in World War Two and helped defend this country. He became [indecipherable] to my nanna. He basically [Inaudible as Dr Carol Dowling speaks over]

Dr Carol Dowling:

He was not indigenous.

Dr Julie Dowling:

So, I, I'm Badimia, I can't be like, I can't identify in my work other than that, even though I use lots of different bits in there. It’s kind of like kind of like embroidery or, or a quilt sort of, you know, you get what you can find to try and say what you need to say. I wouldn't… I, I get a lot of people saying, well, what kind of art do I do? And someone was trying to say, I'm a maximana… maximalist or something. And I don't really like defining any of that because in order to have a comment as an artist, you need to have artistic freedom. And that's really to deba, debatable in a country that sort of, you know, has a hard time with what subject matter might be and I do get a lot of trouble for what I paint about. So…

Professor Alistair Paterson:

Look, I reckon that’s….

Dr Julie Dowling:

…one day, when I'm not here, they can argue about it.

Professor Alistair Paterson:

Well, I'm going to give you and Carol something to argue about because I'm going to let you... have finished with you having had the last word. So, guys can talk about that later on.

Look, I want to thank everybody for helping us decode coloni, colonialism, using language, art, history making and narrative. So, I hope you've enjoyed the panel. Thank you for coming along tonight. And I'm sure if you have any more questions, you can ask Carol and Jane here afterwards as well.

Dr Carol Dowling:

I just wanted to actually, I didn't actually get a chance to acknowledge that we are on Whadjuk Nyoongar Boodja and we have my, my, my son, my foster son and his family are descendants from Yagan, and this is their country. And I'm very proud of them. But I did want to say a little bit of some words in Badimia because it's an endangered language. And, you know, it really means a lot to us to bring that spirit into this space.

So, I just wanted to share that with you,

[speaks in Badimia language and then translates below]

G’day, I'll give you my good wishes and spirits. Our grandmother and mother's sacred country is far away from here. It's Emu and Wedgetail Eagle Country. Our sacred country is abundant with many flowers, food and waterholes. And it's good magic there. And tonight, we return there in our mind and so we think about that place all the time, our country.

Professor Alistair Paterson:

Thank you.

Audience:

[applause]

Professor Alistair Paterson:

Alright, we’ll finish there, thanks to WA Museum. And I just got to say, those kids at the back you brought with, you have been the best-behaved members of the audience tonight. After sitting through all of that, Thank you.

Dr Carol Dowling:

They better be.

Outro

Thanks for listening to In Conversation brought to you by the Western Australian Museum Boola Bardip to listen to other episodes from this series, go to https://visit.museum.wa.gov.au/episodes/conversation where you can listen to a range of talks from past and current seasons of In Conversation and more. In Conversation is recorded on Whadjuk Nyoongar Boodja, The Western Australian Museum acknowledges and respects the traditional owners of their ancestral lands, waters and skies.

More Episodes

A compelling discussion shedding light on the distinctive narratives of those openly embracing their HIV-positive status and what this has meant historically and in today's world.

Meet Professor Kliti Grice, the West Australian Scientist of the Year 2022, as she embarks on a quest to decipher the Earth's past mysteries.

Join a panel of featured young LGBTQIA+ writers and storytellers as they delve into the fantastical realms and real-world struggles of the exciting new anthology, An Unexpected Party.

Explore Australia's dinosaur legacy with Dr Stephen Poropat as we better understand the science behind the scenes of Australian palaeontology!

As we inevitably move towards cleaner, more sustainable forms of energy, how will a shift away from traditional mining practices transform this economy? A panel of experts explore the implications of this shift with a specific focus on how we see ourselves in a world that increasingly demands environmental responsibility.

Join Megan Krakouer, a prominent Aboriginal leader, as she discusses the nuances of her surprising change of heart on the Voice to Parliament — just a week before the referendum.

Join host Michael Mills in a captivating live recording of the Palaeo Jam podcast during National Science Week!