Dr. Henry Skerritt: The art of Meeyakba Shane Pickett

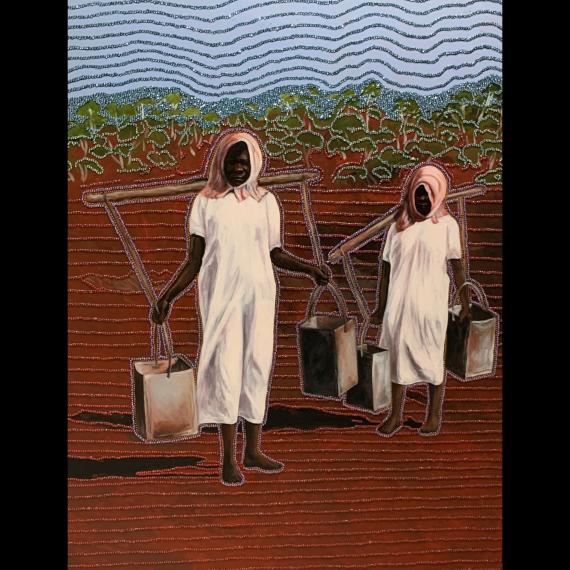

Join us for an insightful talk with the esteemed Professor Henry Skerritt, as he takes us on a journey exploring the captivating art of Jdewat/Ballandong artist Meeyakba Shane Pickett.

With a career spanning over three decades, Pickett explored various styles and subjects, but it was his persistent muse, the Six Seasons, that remained his most profound motif.

To coincide with Pickett's exhibition Six Seasons at WA Museum Boola Bardip, Professor Skerritt delves into the artist's fascination with this subject. Through extensive interviews and conversations with Pickett, Skerritt argues that in the cyclical change of the seasons, Pickett found a way to not only celebrate Nyoongar life and culture but also to present the complexities of living across tradition and modernity.

By capturing the essence of the six seasons, Pickett found a way to represent both the situated nature of Indigenous knowledge and the landscape's ability to bear witness to the unfolding of time. His images are powerful and enduring, speaking to the specifics of Nyoongar culture while highlighting our shared humanity.

Delve into the cultural perspective of Meeyakba Shane Pickett's art and discover the beauty and depth of the Six Seasons.

About speaker Henry Skerritt:

Henry Skiritt is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Art at the University of Virginia and Curator of Indigenous Arts of Australia at the Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection of the University of Virginia. He has curated over twenty exhibitions in the United States and Australia, including No Boundaries: Contemporary Aboriginal Australian Abstract Painting (Nevada Museum of Art and touring); A World of Relations (Hood Museum of Art) and Irrititja Kuwarri Tjungu | Past and Present Together: Fifty Years of Papunya Tula Artists (Kluge-Ruhe and touring). Since 2015, he has worked with Yolŋu artists and knowledge-holders to curate the exhibition Maḏayin: Eight Decades of Aboriginal Australian Bark Painting from Yirrkala. Along with W. Waṉambi and Kade McDonald, Skerritt edited the major bilingual catalogue to accompany the exhibition. Skerritt has written extensively on Aboriginal art, contributing to major exhibition catalogues for institutions including the National Museum of Australia; Harvard Art Museums; and the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Skerritt holds a Ph.D in art history from the University of Pittsburgh and a Masters in Art Curatorship from the University of Melbourne.

This program has been organised in collaboration with Sheridan Institute of Higher Education and the Indian Ocean Research Centre.

-

Episode transcript

Welcome to the Western Australian Museum Boola Bardip Talks Archive. The WA Museum Boola Bardip hosts a series of thought-provoking talks and conversations tackling big issues, questions and ideas, and is delighted to be able to share these with you through the Talks Archive. The Talks Archive is recorded on Whadjuk Nyoongar boodja. The Western Australian Museum acknowledges and respects the Traditional Owners of their ancestral lands, waters and skies.

Mark Fielding: Well, good evening, everyone. Welcome, ladies and gentlemen. My name is Mark Fielding. I'm one of the directors of the Indian Ocean Research Centre at Sheridan Institute of Higher Education, and together with our wonderful partners here at the Western Australian Museum Boola Bardip, it is my delight and pleasure to welcome all of you to this presentation on the art of Meeyakba Shane Pickett, by our special guest Dr Henry Skerritt.

Ngaala kaaditj Whadjuk Nyoongar moort keyen kaadak nidjar boodjar. We acknowledge Whadjuk people as the original custodians of this land, and we pay respects to their Elders past, present and emerging. The Indian Ocean Research Centre was was recently established at Sheridan Institute of Higher Education in order to create a teaching, collaboration and research focus on human activity, past and present, in this very important region, particularly for us here in Perth. It is curious, however, that when you look at other such academic centres and policy initiatives on the Indian Ocean region, there is often little, if any, attention given to one of the oldest and most stable cultures of the region, namely Australian Aboriginal culture of the western part of the continent – to almost imply that Indigenous Australians of the west somehow don't quite fit into the people of the Indian Ocean region. We think this is an omission in an era of scholarship and interpretation and we think it needs to be corrected.

We know the Indian Ocean had a significant impact on Indigenous peoples and cultures, particularly those living adjacent to it. For example, we believe during pre-colonial times, for many thousands of years, the Indigenous cultures of the Shark Bay region, namely the Malgana, the Nhanda and Yingkarta people, interacted closely with the coastline and the bay, trapping fish, collecting seafood and naming significant parts of the region.

Our approach at the Indian Ocean Research Centre is a multi-discipline engagement with all human cultures and activities on and around the Indian Ocean, whether it be East African, Red Sea Arabic, Indian Subcontinent, South East Asian, or in this case, Western Australian Indigenous culture. So it is appropriate and a delight to host this talk by Henry Skerritt on Meeyakba Shane Pickett, one of the most significant Nyoongar artists of his generation, and I would argue one of the most significant artists of the Indian Ocean region. Dr. Henry Skerritt is an Australian born scholar who now resides in the United States. He is currently assistant professor in the Department of Art at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, and curator of the Indigenous Art of Australia at the University's Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection. If I'm not mistaken, this collection in Charlottesville is one of the few major Australian Indigenous art collections outside of Australia, and that's an outstanding outcome, isn't it?

Henry holds a doctorate in art history from the University of Pittsburgh, and in addition to curating many exhibitions in the United States and Australia he is an active researcher and writer in his preferred field of Australian Indigenous art. Henry is here this evening to share with us his research and his understanding of the art of the late Meeyakba Shane Pickett. Henry will speak for around about forty or fifty minutes and afterwards there may be an opportunity, some questions for the roving mike, which you'll notice our assistants will have.

Ladies and gentlemen, we are so privileged to have such a leading scholar in this field with us this evening. Please join me in welcoming Henry Skerritt.

<applause>

Henry Skerritt: Brilliant. Well, thank you Mark and all of the staff at the Sheridan Institute and the Indian Ocean Research Center, along with the West Australian Museum, for inviting me to give this lecture in this extraordinary space, surrounded by these amazing paintings of Shane Pickett's. And I'd like to, really, to thank you all for coming tonight. I think the last time I did anything in Perth with a $10 cover charge, it was probably at the Rosemount Hotel back when I was mis-spending my youth playing in rock bands. But it's great to be back here in my hometown of Perth, the lands of the Whadjuk Nyoongar people, and I would like to pay my respects to their Elders past and present, as well as those of the neighbouring fourteen clans who stewarded Nyoongar boodja since time immemorial.

On the topic of Elders, this is a wonderful event because I get to speak to my parents, Paul and Margaret Skerritt, who are in the front row, ah, second row. My sister told me that meant I wasn't allowed to swear. I'm not quite sure what she was expecting. And I'll tell you, there's a little bit of pressure delivering a lecture on the art of Shane Pickett to a hometown crowd. It's certainly very different to my recent experiences working in the United States, because I'm sure that there are many of you here who knew, loved and respected Shane during his lifetime. So, for all of you, I would just like to acknowledge your presence, acknowledge any friends and family of Shane, as well as Diane and Dan Mossenson, his long time advocates and gallerists.

But I have had a little bit of experience talking about Shane recently because between September 2018 and October 2020 the exhibition Djinong Djina Boodja (Look at the Land that I Have Traveled) made its way across the USA, traveling to Washington, DC; Charlottesville, Virginia; Reno, Nevada; Knoxville, Tennessee; and Peterborough, New Hampshire. I was lucky enough to get to go to most of these shows, and in speaking to American audiences, I was tasked with explaining the relevance of Shane's work in a global context, revealing the nuance of these paintings and their subtlety to people who didn't know him and to people who would likely never even see the landscapes that are so lovingly rendered in his work. Returning to Perth, it would seem like there's very little need to explain Pickett's importance. His work seems almost omnipresent. It's an interesting moment. We have exhibitions of Shane's work here at the WA Museum, across the road at the Art Gallery of Western Australia, and there's many public works around the state that Shane completed. Since his tragic death in 2010, his profound influence on a younger generation of Nyoongar artists has seemed to come quite sharply into focus. Indeed, when I was growing up in Perth, Shane was something of a local legend with his impish smile and sense of humour. People warmed instantly to Shane, and there's a, there's a video in this exhibition in which Richard Walley very aptly describes Shane as someone who was a millionaire in respect.

And yet being familiar with this work and indeed the country that inspired it, there's always a lurking danger that familiarity breeds complacency. Those who knew Shane will remember him as a deep thinker, a patient teacher, and a restless intellect. You might recall how he always cleared his throat <clears throat>before launching into lengthy poetic discourses on art and culture. In long, winding sentences he would circle around ideas. Conversations would snake around themselves, beginning in one place before heading in several different directions, before reappearing unexpectedly where they began, often several days later. And this wasn't because Shane was unfocused, nor was it because he was trying to confuse. It was because he was chasing ideas that were extraordinarily hard to pin down. And it's for this reason that we must return to his paintings for, as sophisticated an orator as he would become, paint was always the primary platform for Pickett’s philosophical endeavours. So tonight, I'd like to take you on a short journey through Pickett's career in order to try and do justice to some of the complexity of ideas put forward in these works.

In doing so, I'd like to argue that while rooted in the landscape, language and lore/law of the south west, Pickett's work is planetary in its ambition. Beyond being strikingly beautiful, the enduring power of Pickett's paintings are their ability to balance with the culturally specific, i.e. the Nyoongar cultural worldview, within a universal context of shared humanity. By capturing the essence of the six seasons, Pickett found a way to represent both the situated nature of Indigenous knowledge as well as the landscape’s ability to bear witness to the unfolding of time. In the cyclical changes of the seasons, he found a way not to only, not only to celebrate Nyoongar life and culture, but also to present the complexities of a world of tradition and modernity.

The son of Dorcas and Fred Pickett, Shane was born in 1957 in the farming town of Quairading. For those of you that don't know, it's about 160 miles due east of here, ah, 60 kilometres— 160 kilometres. I've got to get out of my American brain. Since the mid-19th century, these lands have been stripped and cleared by the invaders. Renamed the Wheat Belt, the region became central to agriculture in the southwest, leaving little trace of pre-colonial topography that had long sustained the Nyoongar people. Despite this, Pickett grew up in a uniquely Nyoongar milieu. Living on the Badjaling Mission, he belonged to an extended community in which Nyoongar phrases still peppered the speech, and hunting, fishing and camping remained cherished pastimes. Surrounded by athletic siblings but suffering from rheumatoid arthritis, he gravitated to art from an early age. In fact, he reminisced, “I can't recall a time when I didn't have a pencil or a brush in my hand.”

After moving to Perth, a chance encounter with the art dealer Tai Ward-Holmes led to his first solo exhibition in 1976. The exhibition was a sellout and launched Pickett's career as a producer of popular, picturesque landscapes and magic realist dreaming tableaus. Important thing to remember here is that in 1976, the Aboriginal art market was very much still nascent. Pickett was an urban Aboriginal artist more than a decade before the success of east coast artists like Gordon Bennett and Tracey Moffatt brought cachet to that label. In forging a career as a full time professional Aboriginal artist, Pickett was very much pioneering an uncharted path. If this path brought him some financial security and local fame, it was only in the final five years of his life that Pickett was able to break from these provincial confines and ascend to the upper echelons of the Australian art world.

There was, however, one precedent for Pickett to draw upon, and that was the school of landscape artists that emerged in the mid 1940s out of the Carrolup Native Settlement near Katanning. By the 1970s, artists such as Revel Cooper, Parnell Dempster and Reynold Hart had a significant local reputation and had created a template of visualising the landscape of the south west. This rather fantastic untitled work of Pickett's from 1976 fits recognisably within this genre, with balga trees framing a foreground that quickly recedes to a flattened schematic background, very characteristic of the Carrolup School. But Pickett would soon find his own voice as an artist, as can be seen in the complexity of this landscape from 1979, in the collection of King Edward Memorial Hospital.

That's worth, kind of, spending a bit of time looking at this painting. The crispness of the light and the sharp colour contrasts of the Carrolup style remain, as does the slightest hint of the theatrical schemata that defines painting from Carrolup. At the same time, there’s a delicacy of paint handling and an accomplished sense of recession that shows Pickett expanding the range of his influences, drawing upon two of the most important Australian landscape traditions: the Heidelberg School of Australian Impressionism and the School of the Central Desert watercolor paintings that emerged from the Western Arrernte community, Hermannsburg, particularly around Albert Namatjira. These two influences are poignantly married in this composition, for the haunting ghost gums that clearly are inspired by Namatjira, which frame the image. But the view itself in both style and subject matter seems much more like the late works of someone like Arthur Streeton. And here’s a good example of one of those. Sort of worth kind of doing a little bit of visual analysis of them.

So in Streeton’s image here you can see on the left, the landscape is positioned as a sight of prosperity and national pride. It's really in the title, Land of the Golden Fleece, and in taking on that influence, Pickett's work evokes this sort of nationalist sentiment but it's, the sentiment is slyly subverted by his reference to Namatjira, which acts as a haunting reminder of the Aboriginal dispossession that underlies Australian nationhood. And the political tension that Pickett's painting creates between these landscape traditions is, I believe, far from coincidental. Arising roughly contemporaneously, the Hermannsburg and Carrolup traditions represented very specific historical responses to mid 20th century colonialism. They were, we might say, the first blossoms of a tentative, growing resistance to colonisation that was taking hold among the Indigenous communities globally. In an era in Australia in which assimilation remained official policy, Carrolup and Hermannsburg styles allowed for the communication of Indigenous connections to Country, camouflaged within a palatably European medium. For many years, the spiritual and cultural underpinnings of Namatjira’s work went largely unnoticed, but it was precisely in the late 1970s, the time that Pickett painted this landscape, that critics began to discern the subtle ways in which Namatjira used mimicry to present a concealed Indigenous vision of the landscape.

Through this tactic, theorists such as Ian Burn and Ann Stephens argued that Namatjira created a double vision which articulated a crisis of authority in which the hierarchies of Western vision were disrupted. In Namatjira’s art, they declared, for the first time the landscape looks back at us. It meets us and deliberately crosses the viewer's gaze of possession. By the early 1980s, as issues such as land rights and Aboriginal self-determination started to gain momentum, Pickett, like many of his peers, began to seek a more assertive version of Indigenous identity. His confidence in his Aboriginal identity was matched with his increasing visibility in the local community. He moved in a circle of supportive and ambitious young Nyoongar men, which included the writer Richard Walley, the actor Ernie Dingo, and the artist Tjyllyungoo Lance Tchad. Using the skills that he learned as a landscape painter, Pickett moved into the realm of magic realism.

Many of you might know this painting from the Art Gallery of Western Australia. I think it was one my son quite liked. And this painting Waagle - Rainbow Serpent shows his mastery of this genre. Swathed in atmospheric layers of paint, the work is a lurid visualisation of the Waagle in the act of creating the Nyoongar people. I don’t know where you can see it, but you've got all of these figures sort of emerging out of the rainbow serpent. If Pickett's landscapes suggested a double vision, magic realism provided a platform through which to bring Indigenous cosmology to the fore. No, there's nothing kind of subtle or hidden in that. The Dreaming narrative is there right on the surface of the canvas. And yet, despite the clear visibility of Nyoongar subject matter in paintings like this, magic realism did not address the deeper challenges of portraying a Nyoongar understanding of the world in paint.

In later years, Pickett often contrasted his paintings to photography, and in, and he said, “In the works that I have made and the life that I have lived, I have been very much honest to nature. Nature is honest, and I try to bring that out. My career has been a journey expanding in scope. As I have grown in maturity my work has become less like a photograph and has tried to explore the deeper meaning of the landscape.” Now, many, many commentators, including myself, have interpreted statements like these as indicating that there was a direct relationship between Shane's abandonment of figuration, and the kind of abstract works that we see here, and his desire to find deeper, more intuitive spiritual meanings in the land. And while this is broadly correct, it does need some elaboration because Pickett's art practice did not flow in a straight line or teleology from figuration to abstraction. He went back and forth constantly. Pickett's 1986 landscape Three Faces of the Sun, which would be awarded the Museum and Art Galleries Award at the third National Aboriginal Art Awards in Darwin, shows him pre-empting many of the same concerns that would dominate his later abstract paintings.

In a delicate wash of landscape, a delicate wash of watercolour and acrylic, Pickett depicts a characteristically bristly south west landscape. The composition is divided into three vertical sections so that the passage of the eye from left to right matches the passage of the sun from dusk until dawn. It's a technique that's designed to make up for the limitations of fixed perspective. In suggesting the movement of the sun across the canvas, Pickett attempts to picture both permanence and change. Now, as successful a strategy as this is, Three Faces of the Sun also recognises its own limitations. As Pickett knows, the passage of the day has more than three faces. Notably, he does not attempt to seamlessly merge the three phases, but rather accentuates the searing heat in the middle section, creating a glowing foreground that pulls the eye to the centre of the image. This is in contrast to the slow cyclical movement of the day. So, I think this is a tacit acknowledgment that the best that a photographer can capture is a series of frozen instants.

Since the invention of photography, ah— Well, since its invention, photography has caused certain conceptual dilemmas for painters. One group of painters who felt this very acutely were the French Impressionists who had built their entire practice on the idea of capturing an instantaneous impression of a scene. Following the rise of photography, the Impressionists were faced with the obvious realisation that any work produced over a period of time and viewed in time necessarily transcends the instant that it ostensibly claims to capture. One solution to this was to paint the weather or atmospheric effects that the Impressionists termed ‘on the low,’ this tangible, unifying atmosphere that surrounds objects.

In 1890, the painter Claude Monet would declare, “For me, a landscape does not exist in its own right, since its appearance changes at every moment, but its surroundings bring it to life. The air and the light, which vary continually.” This line of thinking would eventually lead European and American, and indeed Australian, artists to increasing levels of abstraction as they strove to produce artworks that were nothing but autonomous aesthetic experiences utterly devoid of external references and detached from any connection to the outside world.

This was simply not the case for Pickett, who even at his most abstract, continued to describe himself as a landscape painter and for whom Country remained the defining source of his identity. In weather, Pickett found the solution as to how his works could be both universal and locally specific. We just need to think about how we experience weather. A storm or a cyclone might be experienced in one place, but it's also a demonstration of how larger climactic forces are manifested in a place. Weather systems cannot be separated from the place they are experienced, but they also move across Country. The experience of weather is thus highly specific to place, but it's also relational. It's experienced individually by people and places but shared with those both near and far within the local, national and global meteorological system.

And in fact, that's a really good reason to think about oceans, right? Oceans do the same kind of thing. Currents that connect disparate places and peoples. This idea mirrored Pickett's understanding of place, as he's beautifully quoted in the forecourt of this museum, “For Pickett, Dreaming constituted the bedrock of existence.” And for this presentation, I'm going to use the term Dreaming, because that was the term that Shane used.

And you'll see in the quote downstairs, it’s this quote, it's, it's something that he referred to often— He described it as this. He said, “Every river, every tree, every rock is important as the Dreaming runs through all of them, connecting all things, including mankind. These are the energy paths of the Dreaming. And they are never meant to be broken. They are never meant to fail.” Accordingly, places are not understood in isolation but through their intersections and connections. These energy paths reveal themselves through the songlines that run across the country and reflect the ancestral knowledge of the Dreaming, when spirit beings travelled across the Earth, creating all things and leaving their presence in the land.

This essence remains discernible to those attentive to its power, those who have learned, in Shane’s words, to read the songlines by careful observation of the natural world. The visual activity of the landscape – the shimmer of a dried waterhole, shifts in light and colour, the blooms in spring – are all tangible expressions of ancestral presence. They are the literal bridge between the phenomenal and luminal realms, the realms of what can be experienced with the senses and what you have to experience with your mind. They are the ways in which Dreaming is made visible. Even in the face of environmental damage and loss, Pickett argued that this Dreaming energy persists, and it's almost worth considering that Monet's first Impressionist painting, which I showed earlier, was itself inspired by pollution. Right? Like, he's responding to the polluted atmosphere of industrial Paris. So it is, in its own way, a kind of response to environmental degradation.

But to quote Pickett: “For thousands of years, Aboriginal people have lived with and understood the connections between ecology, meteorology and songlines that bring as well as disperse the rains, and in practicing this form of culture, we find we have a part to perform in maintaining the balance of life.”

But there's something else at play here, because if Dreaming is observed through this acute sensitivity to changes in the landscape, there's also a sense in which Pickett's paintings are themselves manifestations of Dreaming or embodiments themselves of this ancestral power.

Here is how Shane described the process of starting a painting. He would say, “I get into a rhythm that's within the spirit, and then I get up and I walk around and I get an energy happening inside that allows me to follow a rhythm or a pattern.” In that sense, painting is not a case of representing specific Dreaming narratives or specific sites, but rather a translation of the spirit. This act of uncovering the enduring presence of Dreaming. As Pickett said, “A lot of my artwork is neverending in ways of finding subject matter, and at the same time it's done in ways where artistically it can't be repeated in markings or dot works or whatever brushstrokes I've put on the canvas.” Painting, for Pickett, then becomes then a regenerative act, both literally and spiritually, of keeping the songlines strong by their repeated embodiment, by this repeated act of painting, while allowing future generations, in his words, to live, live and sing their identity.

And so the point I'm trying to get at here is that, rather than depictions of the landscape, these late works of Pickett’s begin to inhabit a space of becoming: this channelling, this energy of Dreaming. This, this rhythm and spirit that he talks about getting into when he starts painting. Take, for instance, one of his best known paintings from the National Gallery of Australia. In On the Horizon of the Dreaming Boodja, delicate beams of light break through an abyss of white impasto, signifying, again, in Pickett's words, he says, “It depicts the birth of life, the breaking through the warmth of eternity, bringing the beginning of the Dreaming boodja, a place mankind calls Earth.” So what it's doing here is visualising this moment when everything is born from the vacuum of nothingness. And in doing so, he creates quite a profound meditation on the nature of being. The viewer, us, is held in suspense, we’re literally stuck in the space between existence and nonexistence, suspended for ever on the horizon.

Again— Deep, right? It’s— <laughs> And although Pickett clearly stated that he did not paint body markings, there is a physical presence to these paintings that invokes both the ritual scarification and ceremonial body painting designs. And it's worth thinking a little bit about what body painting designs constitute, as these sort of designs that you see here in this magnificent 1909 painting of Monok[?]. Unlike Western cosmetics or makeup, in ceremonial body painting— Ceremonial body painting is designed to create a connection to the ancestral realm. It's not about covering the body, covering the external self, but it's about bringing out the inner self. The selfhood that is designed, derived from connection to Country and ancestors. So one of the things that you often hear when Indigenous people talk about body painting is that they're bringing out their essence. It's about bringing out their totemic relationships.

In his final years, the pace and consistency of Pickett's progress was astonishing, pushing to ever greater levels of confidence and sophistication. In Djilba Calling the Sun for Warmth and Spring Time from 2008, which you can see for yourself at the end of the corridor, Pickett's characteristic horizon line begins to be warped upwards in a straining presence. As the large sections of white at the bottom of the canvas rise to a crescendo of opaque green, blue and orange, the entire landscape seems to pull itself upwards, rising to meet the promise of spring. The calming sense of anticipation that's present on the horizon of Dreaming Boodja, is given here a strained urgency, this very breathless sense of coming into being.

But perhaps the most radical departure in Pickett's late works was his full scale abandonment of the horizon line, which had until this point provided the characteristic foundation for most of his works. So, now, this kind of stark horizon line was something that really dominated Shane's works for a number of years. But around about this point, 2007, 2008, those horizon lines themselves began to disappear. This painting, Medicine Grounds That Become Ready During Bunuroo swirls with a turbulent depth. Wisps of translucent electric blue offset against gestural areas of opaque white and gray. That, the most subtle pink and orange highlights seep through the chaos, lending warmth to the play of paint that hovers above the emphatic black ground. At the centre of the canvas, the dark ground takes hold, drawing the eye inwards, which is tantalisingly led there by a delicate trail of dots. It is as though the Earth is thrusting from within, shedding its skin in readiness for this healing function. The philosopher Edmund Husserl said that the horizon presents a limit, but not boundary. It was, he argued, a determinable, but never fully determinable in determinateness. Ah, God, philosophers, what do you do with them? It was a deter— They just make shit up, don’t they? Oh, no! Swore!

The horizon is always expressed as a beyond, something we can see, we can sense, but it's always receding. It's always beyond reach. Right? That's what Husserl means when he says it's a determinable but never fully determinable indeterminateness. Right? The horizon, it just keeps kind of going backwards. It's like the pot at the bottom of the rainbow. You never quite catch it. Pickett’s move in puncturing the horizon is to go from a state of anticipation to one of presency[sic]. Right. We don't, no longer have that sense of anticipation that we're on the cusp of becoming, but rather there’s this happening. Right. That's a very phenomenological kind of distinction between becoming and happening. Pickett's paintings move from capturing this instant, as in the photographic record, to existing in a sort of a state of everywhen.

Nick Tapper has noted the pivotal role that the lines of dots play in Shane's late paintings. Unlike many Western desert artists, Pickett's dots operate as independent lines rather than as border or infill. Pickett referred to these dotted lines alternately as travel lines or as the path of the stars through the night sky. Tapper argues that given the centrality of astronomy to Nyoongar sense of navigation and place, these two readings need not be separated, but they’re braided together in the resonance of being at once in place and all places, in place and between places.

But the question I have is whether it's even appropriate to call these paintings landscape paintings. Although Shane asserted repeatedly that he was a landscape painter, in the final years I believe he transcended the boundaries of the scape. Abandoning the horizon allowed Pickett to create pure climatic events. Paradoxically, as arthritis crippled his body, making holding brushes increasingly difficult, he became increasingly physically involved in his canvases. Using his hands to push and smear paint across his works, it was as though he would excavate the Dreaming from the canvas to find its hidden stories, to uncover these truths. The paintings became indexes of Pickett's movement in much the same way that the landscape is indexical of the ancestral travels during the Dreaming. Taking on the power of weather, his paintings become an invocation of both Country and Dreaming. I'm inclined to think that in his paintings, Pickett found a way to connect himself to the landscape. That, as he matured, he no longer saw a division between the artist, artwork and Country, but rather realised that they were conjoined.

This strikes at the heart of Pickett's call to the truth in landscape. Rather than merely seeing beyond the skin and hair, he was sensing that there was no separation between the inside and the outside of the landscape. His identity came from the Dreaming, something that flowed through him just as it connected him to every other being on the planet. As a Dreaming subject, Pickett had found a position that was both situated and relational, in which our differences are not erased, but rather connected like disparate nodes of these flowing energy paths.

I last saw Shane Pickett in the week before his death, and he was busy putting the finishing touches on a series of delicate, figurative landscape paintings that were destined for a solo exhibition in Melbourne. The spindly gum trees and gently undulating hills glowed with an outback haze against the white walls of the studio. There could be no mistaking these paintings as Pickett's. They bore all the characteristics of his mature hand and the same hand that rendered Three Faces of the Sun nearly a quarter of a century earlier. But there was something different. There was an incredible mystery to these works. They were no less precise, but they were breathier, as though the land had become shrouded in a translucent veil. When I look back upon these paintings, I can’t help wonder whether Shane realised that his time on the Earth was nearing a close. There is certainly an elegiac quality to many of them in breaking through light after the rain – which I’ve shown here – a gust of paint moves in from the right. It is as though the land might be lifted from the canvas, as though it could be blown across into space, sucked into the flux of the songlines.

Pickett was seeing place, but he was also looking across it in both space and time. In 2008, he was quoted as saying, “My paintings create a window onto the past. I travel through this window and I bring back the markings of my ancestors into the present day.” Smearing paint across the canvases in his final years, Pickett became so involved physically in them. He described that process as a very, very ancient, old technique: the healing manner used to spread ochre on the body during ceremony. But Pickett's struggle with paint was not at the service of revealing its autonomous material essence, which is something that Modernist painters in the wake of Clement Greenberg often talk about. It's rather to point at the inherent connectivity of all materials.

It was a struggle to unite the pictorial and the physical worlds. Like ceremonial body painting, which manifests ancestral energy, uniting the wearer with the ancestors in their Country, the performance of Pickett's late canvases represents his becoming one with the ancestral realm. Revealing the truth in the landscape was not about seeing beyond the horizon. It was about healing this rift between the Earth and our understanding of it. As he matured, I don't think that Shane saw a division between the world, between his art and himself. They were, they were all a single part of his experience. These late works record his attempt to connect himself to the Earth of Dreaming. His identity came from the Dreaming, and it was something that flowed through him just as it connected him to everyone else.

So I think then it is only fitting to end with Shane's words. “For the dreams do flow strongly through the views of my life.” Thank you.

<applause>

Audience member 1: Oh, so, thank you. That was wonderful. Um, could I ask for your, if we could know your understanding of songlines, the meaning of songlines? When Shane, you mentioned calls them travel lines and lines of the stars, but we're familiar with the term songlines. What, what is your understanding of that?

Henry Skerritt: I think that's two questions. But let me kind of say, for the sake of this argument, it doesn't really matter what I think, but I'll go with what I think Shane was talking about. So, <clears throat> if we think about Dreaming in the sense of, you know, On the Horizon of the Dreaming Boodja, right, the world coming into being. The world comes into being in a very specific way, and that is that the world is an amorphous place in which ancestral beings move across the Earth and they, by their actions and their movements, create various places. They create the lore/law of those places. They create the songs of those places. They create the narratives that go with those places. But by virtue of the fact these ancestral beings move, they create linkages across— So that's what I would say is the songline, right? Literally the lines of the songs that all connect up because these ancestral beings are moving across country.

And so when Shane looks at paintings of the stars, so when he says that they're, you know, the songlines, he's thinking about these travels across space, but he's also thinking about their continuation of place, the fact that the ancestral essence remains in those places and can be linked up. All of those places can be linked up. I remember one fella from Arnhem Land describing it as that the songlines were like the world's most beautiful GPS because if you knew all of the verses of the songlines, you could move across the country any way you wanted.

Audience member 1: Thank you.

Henry Skerritt: I suspect that doesn't make it any more clear, but it's a very, just a very complicated thing.

Audience member 1: So we've always heard is that it's, it's the people moving across the land that, that are the songlines. You said ancestral beings: that’s ancestors or creating, ancestral creating, creative beings, creation beings?

Henry Skerritt: The, yeah, the latter, the powerful ancestral creation beings. But you see, everything that the ancestors, you know— Everything that an ancestral being does gets replicated by their descendants. And so the act of painting is a regenerative act, it is a renewal of all of those things. It's a keeping, it's a maintaining a constant connection to those ancestral beings. So, for instance, you know, when we talk about body painting, and this is particularly the case for artists at the top end when they talk about painting their bodies for ceremony, they're talking about wearing the marks that their ancestors created on the landscape in the first instance. So they're uniting themselves both with the ancestor and the place that the ancestor created. So, you really have to look at these things in a kind of a triangular way, in which they're all connected. Then they're not necessarily separated.

Audience member 1: Thank you.

Audience member 2: Thank you for a wonderful talk. We've certainly lost a great artist. And he was at one with the land, but he was also a person in his own right and had his own experiences through life. Looking at those last works, it looked like he was at peace, ready to depart. Those very last works, 2009, that you said were going to Melbourne—But the works in 2008 where the, the horizon line got morphed into a much more chaotic sort of representation on the canvas: was that something that he was going through personally, with his own experience perhaps recognising that, the end of his time on the, on the Earth?

Henry Skerritt: Yeah, I don't know the answer to that. What do you think Diane?

Diane Mossenson: I don't think it, the horizons in turmoil reflected where he was at personally. I think it was just him exploring artistically the direction he wanted to go in, be— And I don't he felt the mortality of life at that point because he was embarking on new directions and had new projects ahead of him. So, I think his untimely death was really unexpected for all, and he just wanted to keep pushing the boundaries of what he did artistically. And the reason he returned back to the landscapes in the last show was that in 2010 he was planning to embark on a sculptural practice and leave painting behind. So he kind of was doing those landscapes as completing the circle of his artistic career and sort of ending where he began. And then he was going to go on to new things. And perhaps he finished those landscapes, perhaps with some more sentimentality and mysticism, I think, around what he was doing.

Audience member 3: I'm afraid this question isn't quite as intellectual as your presentation, maybe a little bit more historical, but it's about dots. I have a— Shane’s paintings in my office with a row of dots across it, which I ponder quite often. My understanding—maybe quite wrong— is that dots are regarded as almost ubiquitous in Aboriginal painting, except that they really came from one particular area where they've spread around. And they appeared relatively late in Shane’s career. Little, little tiny dots wandering across. I wondered if he picked that up from the rest of the, the history of dots in Aboriginal painting?

Henry Skerritt: So that's a really, that's a really long and complicated answer to that and part of— I think there's another story that runs through Shane’s career, and I was thinking about this today, looking at the sets that he produced for Kullark - The Dreamers, a Jack Davis play in 1986. And if you think about the 1980s and that emergence of Indigenous identity, of which Shane is a part, and plays like Kullark - The Dreamers are really very evocative of— You know, Shane was trying out a lot of ideas. He was doing a little bit of crosshatched X-ray style kangaroos. He was doing a little bit of dot work. And he was very much pulling together a kind of a pan-Aboriginal toolkit of iconographies and styles. Having said that, I mean, dots are a very human thing and, and whilst in contemporary Aboriginal art they do tend to get associated with Western desert painting, they do appear in all sorts of art. They're not exclusively Western Desert painting. And so, I mean, I think even if you looked at that picture of Monach[?], he probably had some dotting on his chest as well. So, you know, I think, I think the answer to that is a complicated one. On the one hand, I think, yes, Shane is definitely using dots as a sort of a symbol of Aboriginality, that they fill the space of allowing his paintings to have something that is noticeably Aboriginal. He's certainly doing that, right. He needs that. He needs that to kind of assert the Indigeneity of the paintings. But they become less and less present in his work and he— They become, they, they begin to be very much a formal device for thinking about movement, for thinking about these ancestral travels.

But also, I mean, they're also used formally. He's using them to move you, move the eye into certain parts of the canvas. I don't know that that entirely answers the question, but it's a very complicated question. I mean, the shows were incredibly well received and I think, you know, a lot of that speaks to, you know, one of the key points that I was making here, is that these works, I think, were intended— You know, on the one hand, there's a journey in these works that is, is Shane sort of deepening his own understanding of Nyoongar culture and, you know, trying very hard to produce these very characteristically Nyoongar paintings, and paintings that could then be taken up and influence younger artists. I think on the one hand he's doing that, but he's also doing something that is very cross-cultural. There's a lot of, there's a lot of cross-cultural work being done here where he is trying to use these paintings to explain these ideas. Shane quite liked explaining his ideas. He would, he would talk at length about his philosophies. And so I think that that dual element of paintings that are actually strikingly beautiful— You are meant to enjoy, right? You are meant to get lost in. Your eye is meant to move across the canvas in interesting ways. I think that is, you know, something that appeals universally while still being very specific. I mean, that's the thing that makes these paintings great is they are these two things simultaneously. They're very, very specific and from a very specific place but at the same time, they're also, every— Anyone can love them.

Audience member 4: ...early work. Sorry. I grew up in the Pilbara and my memories of the Pilbara are exactly what, sort of, he, he's painted. The red dirt underfoot and getting the spinifex out of my, you know, the bottom of my feet. So, you know, it resonates with me. And thank goodness that we've got artists like him and others who can sort of keep those memories alive.

Henry Skerritt: Think that's a nice spot to end.

Mark Fielding: Well, wasn't that wonderful? Henry. A wonderful presentation, Henry. Absolutely fantastic. And, you know, Henry has met Shane, knows Shane, has interviewed Shane and brings with that personal knowledge the expertise that he's developed over many, many years. What a fantastic presentation. You know, the thing that— I mean, there are many things I could take away, but the one that I'm going to keep, and I wonder whether you can identify with as well, is Henry's comment about the emergence of Indigenous identity in the 1980s. And if you think of Shane's career, just as an amateur like I am, it kind of, it kind of mirrors it, doesn't it?

You know, his artistic expertise and presentations kind of generated from that time. And then we saw them evolve over time as well, just like we've seen the development of Indigenous culture evolve into what it is in the 2020s. So in many respects— I mean, he was his own person, there’s no doubt about that. But in many respects for me, listening to that presentation, there was a great parallel to the development and, and renaissance of Indigenous culture. A fantastic presentation. I hope you enjoyed it. I have a little gift on behalf of all of us to Henry, but please thank him again for coming and sharing that with us. This is a little thank you. <applause>

Thank you so much for coming. I hope you enjoyed it. I'm sure you did. Thank, my thanks go to the WA Museum for hosting us. Very, very, you know, Ruth's done a great job, and the team. Thank you so much. <applause> Thank you so much for coming. God bless you all. <applause>

Thanks for listening to the Talks Archive brought to you by the Western Australian Museum Boola Bardip. To listen to other episodes go to visit.museum.wa.gov.au/episodes/conversation where you can hear a range of talks and conversations. The Talks is recorded on Whadjuk Nyoongar boodja. The Western Australian Museum acknowledges and respects the Traditional Owners of their ancestral lands, waters and skies.

More Episodes

A compelling discussion shedding light on the distinctive narratives of those openly embracing their HIV-positive status and what this has meant historically and in today's world.

Meet Professor Kliti Grice, the West Australian Scientist of the Year 2022, as she embarks on a quest to decipher the Earth's past mysteries.

Join a panel of featured young LGBTQIA+ writers and storytellers as they delve into the fantastical realms and real-world struggles of the exciting new anthology, An Unexpected Party.

Explore Australia's dinosaur legacy with Dr Stephen Poropat as we better understand the science behind the scenes of Australian palaeontology!

As we inevitably move towards cleaner, more sustainable forms of energy, how will a shift away from traditional mining practices transform this economy? A panel of experts explore the implications of this shift with a specific focus on how we see ourselves in a world that increasingly demands environmental responsibility.

Join Megan Krakouer, a prominent Aboriginal leader, as she discusses the nuances of her surprising change of heart on the Voice to Parliament — just a week before the referendum.

Join host Michael Mills in a captivating live recording of the Palaeo Jam podcast during National Science Week!

As AI rapidly evolves, join our panel of experts in an exploration of these complex issues, including how we can harness its power while ensuring responsible and ethical use before we're outrun by its speed.

Do you know how and why your teeth do what they do? Find out all there is to know about teeth sharpening.

Decoding the language of our written and oral histories in Australia.

No, it’s not a card game but a community initiative helping us further our knowledge of a group of endemic land snails Bothriembryon affectionately called ‘Boths’.

Delve into the way Aboriginal industry professionals are shifting representations, decolonising the media space and creating visibility for Aboriginal people in the industry.

Exploring the debate surrounding the establishment of an independent, representative advisory body for First Nations people.

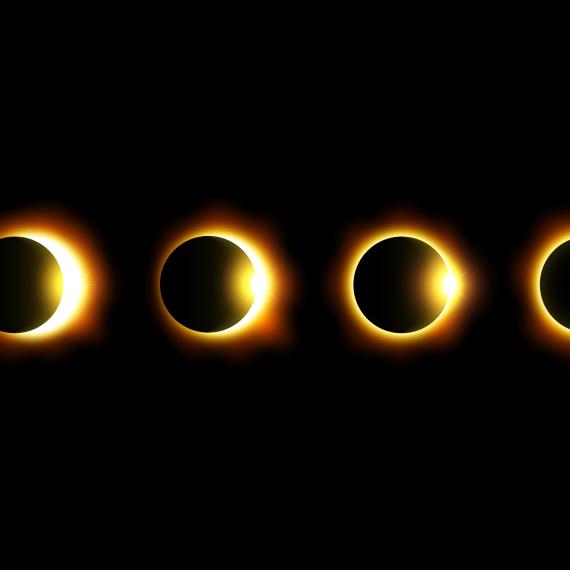

Aristeidis Voulgaris sharesstories from his eclipse chasing travels and discover the complex instruments and tools used in solar astronomy.

Join a panel of experts and community as they investigate the nature of queer bodies, and queer sexuality, in public space.

Join historian Toner Stevenson and astronomer Melissa Hulbert, as they share their tips on how to salute the sun during this eclipse!

Simon Miraudo and Tristan Fidler from RTRFM’s ‘Movie Squad’ are joined by Chelsey O'Brien, Curator at ACMI, as they review and discuss Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland as a foundation for contemporary storytelling in film.

In this one-off Perth Design Week talk, the Museum celebrates the remarkable women in architecture and film in a panel discussion, recorded as a part of its recent award-winning film screening.

Join world expert Dr Chris Mah from the Smithsonian Institution as he recounts his encounters with some of the most unusual creatures on the planet.