Raising the Dead with Paleo Jam

Join host Michael Mills in a captivating live recording of the Palaeo Jam podcast during National Science Week!

Explore the intriguing world of palaeontology and archaeology, two sciences that never fail to ignite the public's imagination. Delve into the mysteries of how ancient artefacts and fossils are preserved, unearthed, and brought back to the lab, even after thousands or millions of years. Discover the secrets revealed by these remarkable discoveries. Listen to Palaeo Jam for an exciting conversation with palaeontologist Professor Kate Trinajstic and archaeologist Dr Sven Ouzman.

Check out Palaeo Jam at https://palaeojam.podbean.com/.

About the speakers

Michael Mills is an award-winning science communicator, writer, producer, and musician known for his captivating storytelling and innovative projects. With over 60 shows under his belt, he has shared the wonders of science and challenged traditional historical narratives.

Professor Kate Trinajstic, a vertebrate palaeontologist, has been contributing to the field since joining Curtin University in 2009. Her research focuses on the development of early vertebrates' skeletons and musculature, earning her prestigious fellowships and awards. With a strong academic background and extensive research experience, she brings valuable insights to her work.

Dr Sven Ouzman, an archaeologist and heritage specialist, has a diverse range of expertise, from studying ancient human occupation sites to contemporary archaeology. He explores rock art, Indigenous knowledge, and intellectual property, shedding light on human interactions with fossils and ancient artifacts. As a Senior Fellow at the University of Western Australia, he shares his knowledge through teaching and research.

-

Episode transcript

Introduction Song:

Let's take a little time to reveal. The pre-historic stories that the earth once concealed. You mix them all together on this ancient land. It's time to spread some Paleo Jam.

Michael Mills:

Welcome to a special episode of Paleo Jam. Thanks to National Science Week, we're in Perth, Whadjuk country, Western Australia, and specifically at the Western Australian Museum Boola Bardip. And there are a whole lot of living organisms, mostly sentient, it seems, in the room. Hello, people.

Audience:

<cheers>

Michael Mills:

Yeah, the people at the back didn't do much, did they? Thank you to the people at the front for being with us. We might try that again. We don't edit this, but anyway. Hello people.

Audience:

<cheers>

Michael Mills:

Thank you for your spontaneity. I'm your host, Michael Mills. And in this episode, I'm joined by a palaeontologist, Professor Kate Trinajstic.

Dr Kate Trinajstic:

Hi. It's great to be here.

Michael Mills:

And archaeologist Dr. Sven Guzman.

Dr Sven Guzman:

G’day everyone. Thanks for coming.

Audience:

<one voice cheers>

Dr Sven Guzam:

<chuckles>

Michael Mills:

That was that was the sole supporter in the audience. The microphone may or may not have picked that up. Okay. So, palaeontology and archaeology are two sciences that regularly captured the public's imagination, whether it's through Hollywood blockbusters such as Jurassic Park or Indiana Jones, there's a very definite fascination by the public. In the recently dead or the long ago dead. The palaeontologists and archaeologists are often confused by the public. And our job tonight is to tell you that they are there are some differences, there are some very clear similarities, but there are some very different, different, differences. Kate, Now, I want to begin by asking you, what is it? Because we talk about two sciences that's so commonly here at the Western Australian Museum, there's an Egyptian exhibition that is going particularly well before that there was a, a Dinosaurs of Patagonia exhibition that was going particularly well. So, palaeontology and archaeology are two of the superstar sciences. What do you reckon it is about palaeontology?

Dr Kate Trinajstic:

I think it's, um, a chance for people to see a whole range of life that was on earth that we don't see today, and people are fascinated by the past, and particularly a past that people weren't part of.

Michael Mills:

Yeah, it's the, it's, it's, it's, almost as if we're talking about real monsters, isn't it? I mean, they're not monsters because there are no monsters in nature. But we, we're, we're thinking about animals, often huge, great big animals that once stopped, swam, flew as well as the tiny ones. But it's that thing of creating a picture of the past sometimes 100,000 years ago, sometimes 100 million years ago, and sometimes in some of the stuff that you work with, Kate, many more hundreds of millions of years ago.

Dr Kate Trinajstic:

Yeah, I, I, I work on fossil fish and people tend to think of palaeontologists as people who only work on dinosaurs. And I think the average six-year-old probably knows more about dinosaurs than I do. But, um, the group I'm working with were the first animals to have jaws and teeth, which we have today, and they were also starting to develop limbs. And so, I'm working in fossils around about 400 million years go to 375 million years ago, and they're the first fossils that have basically the same body plan that we have today.

Michael Mills:

So, we're all fish?

Dr Kate Trinajstic:

Absolutely.

Michael Mills:

Okay. So, what is it about archaeology? Because I went to the Egyptian exhibition today and it was full of people and it's fabulous. And, and, you know, just about everybody, every museum in the world has a whole bunch of Egyptian artifacts. And we'll probably talk about that a bit later as to how that came about. But what, what is it about archaeology?

Dr Sven Guzman:

Thanks, Michael. Well, archaeology is the only discipline to study all of human history in its entirety for, say, the last 3 million years. And the reason for that mostly is because we steal insights and techniques and things from everyone else, really. And, you know, it's ourselves. Where do we come from? Just the notion of an origin is... I don't think we can actually resolve it, but through things like fossil hominins and those kinds of things, we, we both see ourselves a little bit and then don't see ourselves and we, we need people.

I would say this, otherwise I'd be out of a job. But we need archaeologists to figure this all out for us. What people might not realize is that archaeology is the study of the past. As sometimes is said. Everything I've just said is in the past, and so it can extend right to study modern social problems today, for example.

Michael Mills:

So, this podcast will become an archaeological artifact after we've recorded it.

Dr Sven Guzman:

It already is.

Michael Mills:

It already is. I have nothing.

Dr Sven Guzman:

So, archaeology is constantly in production. You know, you're everything you're consuming today and throw away. Thanks very much to keeping the next generation of archaeologists in business. And it's not a frivolous thing because we, we have too much waste, right? So, a lot of archaeologists are looking at climate change and looking at how people disposed of things in the past, how they manipulated the environment. And we even look at things like graffiti and homelessness as modern social issues that we can look at through an archaeological lens.

Michael Mills:

Okay. So, it's, it's seems to me it's very much about getting a sense of who we are, a sense of place, palaeontology, as Kate talked about, you know, the fact that we are at one level, we are all fish. That is also that question of who we are, our sense of where we've come from. And I think more than anything, we're looking with both palaeontology and archaeology. We're looking at stories. We're looking at stories of us as a species. We're looking at stories in natural history, we're looking at stories of individual organisms. And I want to quickly come to the question of what you actually do. What is it? What does it look like for an archaeologist? What is it they look like for a palaeontologist? And maybe we can tease out where there are some differences and similarities. Kate, you've just flown back from being far away. Some other than jetlag. What does your day look like?

Dr Kate Trinajstic:

Well, I guess it depends. So that's the first thing, is that there really is no typical day, which is wonderful and makes it a great job. I would spend most of my time looking actually at the fossils, so trying to work out what they, what they looked like. So, when you're looking at a fossil, you're only ever looking at part of part of the animal. And even with the best preservation, you never get 100 percent. So, you have to try and work out what it looked like in in life. And palaeontology is also very much looking about the environment that it lived in and understanding not just how the animals evolved and change through time, but also how the earth changed through time and particularly how the, the climate has changed as well. Um, also, we would do fieldwork. And so that's very much getting out to the outback of Australia, walking across fantastic landscapes, and hitting rocks with a hammer.

Um, so it's none of this kind of fine paintbrush work for us. My favourite tool is a sledgehammer, particularly because I don't have very much upper body strength, and so I need a big hammer to break the rocks. And of course, there's all the new technology. So, palaeontology is moving more and more to being non-destructive. And so rather than dipping our rocks into acid, we're actually putting them into CT scanners and synchrotron scanners now to see through the rock and do virtual preparation.

Michael Mills:

And we might, we'll come back to, to some of that technology stuff, new technologies for both sciences in a little while. Um, so spend your day. So, is yours more of a paintbrush kind of day?

Dr Sven Guzman:

Well, it depends very much where you work, because archaeology, it used to be you had to be in a museum or a university to get a job as an archaeologist, and you had to wait for someone to retire or die to get a job kind of thing. You could sort of arrange the one, but not so much the other. But these days you can work in all sorts of things. You can be working a native title, you can be working in government entrepreneurship as a consultant, archaeologist in industry, as well as universities and museums. But for myself, it depends which time of year is it? If it's semester, your teaching, your supervising, your fundraising, you're working in the lab from all the things in the field. So, the field, the saying is it's in the field that you find things and it's in the lab that you find things out kind of thing. Then when we go to the field, which is whenever we're not teaching and such like, then a lot of that is depending what kind of archaeology you're doing. Are you archaeobotanist, archaeozoologist or rock art specialist, a lithic specialist. There's, there's an endless sort of list of those. But what's key to those is, is teamwork and group work, not just among archaeologists and fellow scientists, botanist and such like, but a great many communities, particularly here in Australia, Indigenous communities. We see so much history. Most non-Aboriginal Australians are sort of stunningly unaware of the deep history and continuing history of Australia. When I talk about the archaeology of Perth, people look at me like I've been drinking kind of thing. But you know, we've, the whole river is a declared cultural site. We've got 9000-year-old sites in Mosman Park, for example. So, I quite enjoy finding out those things that are really in plain view and bringing them to sort of greater public sort of notice. And then we do outreach in schools and things are, you know, you just make it up as you go along.

Michael Mills:

And that's, that's, that's, that's the cool part of it, isn't it, where you're, you're getting people to better know the place that they live in, the place that they visit. And I guess that's one, we touched on earlier. That's one of the great things about both sciences. It's about getting to know this place. You know, Nova Peris once said, ah, when, when people were concerned about the introduction of Aboriginal stories into curriculums and things, you're not losing, you're not losing the European stories, those stories are still being told. What all Australians are gaining through the telling of these stories, you're actually gaining, we as a people are gaining 50, 60, 70,000 years of stories. One of the great things about living in Australia is that we have a history of people living here for all of that time and all of that is part of the story of all of us as Australians. And this, and we we're talking, we touched on it before the podcast. There's some really fascinating connections between palaeontology and archaeology and Aboriginal Australians. So, in Andyamathanha country which is just north of Adelaide in the Flinders Ranges, there's a story of an animal called Yamati. The story of Yamati is taught, was taught and has been taught for thousands of years to young Andyamathanha kids, to be afraid of this giant angry herbivore. And if you don't think herbivores can be angry, go hang out with a hippopotamus or a rhinoceros or head of cattle. So, some scientists, some, some Western scientists and elders were sitting down, and they've suddenly gone, Hang on a minute. You know that thing in the museum? that's a Diprotodon. And there's bits of it here in the Western Australian Museum.

You know that Diprotodon and that Yamati, it's the same thing, it's the same animal. And so, first nations stories can help inform us about some of these animals of the past. What, um, Sven you were talking about some stories about that.

Dr Sven Guzman:

Yeah. So, there's a scholar, often people say oral histories can't go back that long but there's an established scholarship there for recent publication, ones about ocean level rise for example. In this…. fine…. it's all about stories about translating these different knowledges so that we can kind of understand them. We've got rock paintings of extinct megafauna like Genyornis and Thylacoleo, the marsupial lion across northern Australia. And this fine institution has in its collection a, a pendant collected from the Kimberley, Aboriginal made pendant of Zygomaturus, the large extinct sort of 50,000 year old need to had a couple of zeros for it to come into Kate sort of side of things.

Dr Kate Trinajstic:

<chuckles>

Dr Sven Guzman:

But for me there is that that area where those two meet quite well and people have kept stories not unchanged, no story is changing, but they link to that past and they often talk about these animals and reliably can be linked to extinct animals, particularly in my field, Megafauna.

Michael Mills: Yeah, Kate, are there any paleontological stories that you know of or of working in the field with, with Aboriginal Australians and what sort of issues do you come across?

Dr Kate Trinajstic:

Well, I think the is, um, one of, one of the things we're starting to realize now is that there is a wealth of knowledge and scientific knowledge within the indigenous people that we're just starting to underst… not really understand but, but gain a knowledge of. And one of the things you can also see upstairs in the fossil gallery, of course, the dinosaur footprints from Broome. And there's a wonderful story about the giant emu man that crosses across and leaves these, these footprints and that has actually helped very much with the discovery of where these footprints are, because by following the story, people have been able to actually follow where some of these footprints are. And Steve Salisbury actually said he's gone out and they've kind of discovered some and the indigenous people just look at him as if he's got a couple of extra heads like, well, you know, the stories have been telling us that's where they're there so what do you mean you've just discovered them? We've known you've been there for ages. And so, I think it is about Western scientists appreciating more and engaging more with the indigenous people to actually gain that knowledge and to be able to share that.

Michael Mills:

And it is it's an addition of knowledge. And in addition to the story I wanted, we touched a bit about the question of preservation, and I want to talk about that in terms of, of, of things like there's cave mummies, right? But they're not Egyptian mummies that have been put in caves. But there's that, But up in the collections here, there's this mummified Thylacoleo. So, the process of mummification, there's a there's a natural process of mummification, but there's also a human, although, I mean, obviously anything that we do is natural because are of nature. But then there's the human process of mummification we…we…. through Egypt. So, so what are the similarities? And can I say it open to both of you?

Dr Sven Guzman:

I quite like fossilization as a process. I think that's where we come together sort of. People often say, well, what's the difference between palaeontology and archaeology? Several hundred million years is generally the sort of answer. But the taphonomic processes or the processes by which things preserve both of us only deal with a very small fragment of what there was back in the past. And I often think of fossilization as a kind of place where our disciplines kind of meet. So, it's your sort of meat and drink very often. We don't have it that often in archaeology, it's more in the field of palaeoanthropology, a sort of allied discipline. And it's almost as though when something gets fossilized, it becomes part of that greater human story as you're talking about stories. You know, we're not the first archaeologists or palaeontologists. People have been interested in these things in the past. We find fossils in archaeological layers well after when they should have been there. So quite like those things, the natural mummification people would themselves have noticed these kinds of things. And you sort of wonder when people say, how did they know how to mummify people?

And well, like any scientist, they would experiment, and they would base that on partly what they've observed out in nature and partly what their own capabilities have. And so, we then move into these state level societies where but keeping things for posterity seems to become quite important for me. One of the main things is the sense of perspective the earth sciences gives us in time and place. In most of our history, 99% of human history we've lived as hunter gatherers, not as we live now. That's why you've got gluten intolerance and all of these different kinds of things. So, we'll probably, our bodies probably don't need any preservation because we've got enough preservatives in us as we speak so…

Michael Mills:

The other fascinating thing about the whole preservation thing that I think about in terms of future archaeology and palaeontology is that we, we bury our dead. So, and then I'll come to you in a second, Kate, about the whole question of taphonomy. So, to me is the process by which something becomes a fossil and is then ultimately discovered and taken obviously then taken back to the lab. And one of the first things, of course, to become a fossil, you need to die. The second thing is you need to be buried and hopefully not eaten. We do that in cemeteries and I'm just trying to picture palaeontologists in 100 million years comes across all of the cemeteries around the world where they've got all of these bodies lined up trying to figure out what the heck was going on 100 million years ago to have all of these bodies aligned. Kate, if you're a palaeontologist in 100 million years time and you came across a situation where you had all these bodies lined up, what, what on earth would you think was going on?

Dr Kate Trinajstic:

Mass kill...uh, But one of the.

Michael Mills:

Yeah, yeah, like literally. Yeah.

Dr Kate Trinajstic:

Yeah. But one of the things I learned very early on was palaeontology tells you about where things die, not where they live. So, um, and that's what you have to unravel is, are you looking at a death assemblage or are you looking at a life assemblage where something catastrophic happened and things die in situ? And usually when you find a large number of things dead all, all together, it is something catastrophic that that's happened. Or you're looking at a site, particularly as I work in fish, you might be looking at a lake that... a drought situation where, you know, basically all the water's gone.

Michael Mills:

So, everything's dead!

Dr Kate Trinajstic:

And everything’s dead! Um, where you're looking sometimes at things, where things are, where they lived, you're looking at a landslide. So particularly in the marine system, I work in fossil reefs. Sometimes the reef collapses and then everything's buried where they, where they live. So, a lot of it's unravelling as to are you looking at a situation where things have died in situ or are you looking at something where the animal's died? It's filled with gas. It's kind of floated away a little bit and then exploded and dropped to the, dropped to the ground and there are many controversies in palaeontology, particularly even with dinosaurs. Were they aquatic or were they terrestrial? You know, did they live on land and get washed into the waterways or did they actually live in rivers? And, um, it's a, it's a real puzzle to try and work some of these things out. And sometimes we manage and sometimes we don't.

Michael Mills:

So that catastrophe thing is reminiscent of Pompeii. And Pompeii gives us a sense of, of, of a city a long time ago, but it's a city in the middle of a catastrophe.

Dr Sven Guzman:

Well, catastrophes like that will, will recur and will happen again. You know what we've got to think about. You're talking about death and cemeteries and things, is we need to think seriously about ourselves and, and dying and what we do with the dead. You know, we have to... to declare an interest. I teach a unit on the archaeology of death at UWA. You’re all very welcome. But we have to get rid of about 15,000 tons of human flesh each day. And there isn't enough room in the earth to get rid of that.

Michael Mills:

You know there’s a movie called Soylent Green, right?

Sven Guzman:

Yeah, yeah, we won't. We won't go there so much. And, you know, so it becomes a, it's a major ecological issue that we have. And, you know, what are we going to do about it kind of thing. So, this is where way archaeology intersects with some of the modern things we have. But burial is a very it's one of the hallmarks of humanity. And I include uh, Neanderthals in there. People often get Neanderthals have this bad rap as being primitive and all of that. They had seven different ways of disposing their dead, the same seven ways that we have. We are Homo sapiens sapiens, which is debatable, and they are Homo sapiens neanderthalensis, for example. So, they’re cousins. And it's so it's important for, we’re attracted to burials, you know, the Egyptian mummies and those kinds of things. There's a huge amount of information and we're dealing largely with non-fossilized remains that we can get from isotopes, from the bones, what the environment was like, the grave goods that are with the people, the manner in which, who is and who isn't buried or disposed of, for example. So, um Pompeii is just, you know, the thing there is you don't actually have the bodies, you have the, the negative space. But in that literally the last moments of people, it's a, it's an incredible moment.

Michael Mills:

Yeah. And we see that one of the, one of the one my favourite kinds of fossils were the fossils where you're not just seeing what an animal looked like, you're seeing it in the process of doing something. Kate There are some remarkable fossils that have been found here in Western Australia that you've worked on that are in the process of doing stuff. Could you tell us about that?

Dr Kate Trinajstic:

We have quite a few that have found in the process of eating other animals, so we have a very large fish called Onychodus and it had this kind of, uh, well, it's a tooth whirl, but basically, it's kind of a battery of teeth. We found another little fish kind of lodged in its throat. So, it basically had choked to death. And again….

Michael Mills:

It should have been a vegan,

Dr Kate Trinajstic:

It should have been a vegan it should, it should have chewed it. It was obviously swallowing it whole and bit off more than it could chew. And we have quite a number of fossils that have, have died in the process of actually trying to, to hunt and consume.

Michael Mills:

There was, there was an interesting paper came out recently of a small mammal in the middle of eating a dinosaur. And the media have gone crazy and the paper itself has gone: “Yeah, this, this mammal, and it’s attacked and has eaten this dinosaur. The problem is the problem is it's like you can't tell whether the dinosaur was dead or alive when the small mammal started eating it.”

And that's part of the problem. When you're looking at things that old… the, the, it, it is much more likely that this small mammal is walking past finds this dead thing and has gone. “Oh, I'll have a nibble of that” as it’s had a nibble of that, this catastrophe happens that covers it over and then, you know, 100 million years later people are going, “Oh, look at that lovely mammal. It wasn't all one way.”

Dr Kate Trinajstic:

Yeah. When you actually find a fish stuck in, another fish’s throat though, you could be pretty sure that it choked to death.

Audience:

<laughter>

Michael Mills:

Yes, there is that. We've, we've, we've got about 5 minutes left to go. How crazy is that? I want to go to the dark side for a moment. Both sciences, archaeology and palaeontology, I guess, have suffered from colonialism. There's a really cool series on the ABC called What the British Stole because they knicked a whole lot of stuff without asking the people in particular countries. Theft of artifacts, objects and fossils happens, has happened in both sciences where paleontological heritage has been taken, but also of course archaeological artifacts have been taken from places. We've learned some cool things from them, but we could have learned those cool things in cooperating with the local peoples who had the stuff. Um, where are we at with, with both sciences and how do we do that stuff better? Maybe Sven, start with you first.

Dr Sven Guzman:

Sure. So, there are two things there. The sort of colonial history of archaeology. So, archaeology, anthropology were part of the colonial apparatus of control. When you go to another country, they were figuring out which were those groups of people how to control them, and then taking artifacts, sometimes with permission, sometimes not. It's quite varied. And you've got to avoid you've got to look at things in context, not excusing anything, but you've got to sometimes things were bought fairly or traded fairly. Sometimes they were just taken literally grave robbing. And, you know, sometimes we still have to deal with that legacy. That hasn't happened for a long time. But people have, have long memories, understandably. And so that's why most archaeology today works in this sort of group space. We've got any number of laws, codes of ethics. And anyway, we want to do the right kinds of things. And we've learned from the past. And then the second thing you have is the theft of antiquities and objects and things. And I was challenged when I was curator of archaeology at Iziko South African Museum, to put a dollar value to each of the archaeological artifacts that we had, which is a very challenging thing to do. And you say, “Well, we can't do that” And then I'd say “priceless”. And the auditor’s eyes would light up because they saw priceless as just being a really lot of money kind of thing. And we but we can't benchmark any sort of price because there is a world out there. Just go onto eBay now and type in artifact, either in the US spelling or the English spelling and all sorts of things come up and you can be sure a lot of those are illicit. All of the wars that go on. There, there's a lot of looting that happens actually before the invasions happen. There's a lot of preplanning things we don't necessarily I like to think of. And then, you know, museums like this have-to-have sort of top-notch security as well to prevent the theft. But then there are all the sites out there are millions of sites in both of our disciplines. They can't all be looked after by a law or an authority. And that's where education is really important. For example, selling an artifact for the person on the ground, selling the artifact doesn't make very much money. The middle person does. But stressing the long-term benefits of education and tourism, for example, by leaving those artifacts in situ is much more important. And that's where a lot of our work goes. Our research almost always flips over into sort of management, tourism, engagement as well.

Michael Mills:

Over to you Kate, defend palaeontology.

Dr Kate Trinajstic:

Well, it's, it's a similar sort of thing. I mean, obviously Australia was a, a colony and they've one of the reasons I've just come back from the Natural History Museum in London was looking at Australian fossils that are over there. And again, this kind of pros and cons of these things as well. I mean a few years ago the museum in Brazil burned down, so having artifacts kind of spread across a number of institutions can actually help in their, in their preservation. And I think both disciplines certainly are now moving more to having a greater understanding of removing things from, from country.

And some of the new technologies that we've got now is enabling us, as I said, to look at things non-destructively.

Michael Mills:

On that note, that's a really cool note to finish on. I think a cool positive note for the future. Can we please thank Kate and Sven. My names Michael Mills, you’ve been listening to Paleo Jam here in Perth.

Outro Song:

it's time to spread some paleo jam!

More Episodes

A compelling discussion shedding light on the distinctive narratives of those openly embracing their HIV-positive status and what this has meant historically and in today's world.

Meet Professor Kliti Grice, the West Australian Scientist of the Year 2022, as she embarks on a quest to decipher the Earth's past mysteries.

Join a panel of featured young LGBTQIA+ writers and storytellers as they delve into the fantastical realms and real-world struggles of the exciting new anthology, An Unexpected Party.

Explore Australia's dinosaur legacy with Dr Stephen Poropat as we better understand the science behind the scenes of Australian palaeontology!

As we inevitably move towards cleaner, more sustainable forms of energy, how will a shift away from traditional mining practices transform this economy? A panel of experts explore the implications of this shift with a specific focus on how we see ourselves in a world that increasingly demands environmental responsibility.

Join Megan Krakouer, a prominent Aboriginal leader, as she discusses the nuances of her surprising change of heart on the Voice to Parliament — just a week before the referendum.

As AI rapidly evolves, join our panel of experts in an exploration of these complex issues, including how we can harness its power while ensuring responsible and ethical use before we're outrun by its speed.

Do you know how and why your teeth do what they do? Find out all there is to know about teeth sharpening.

Decoding the language of our written and oral histories in Australia.

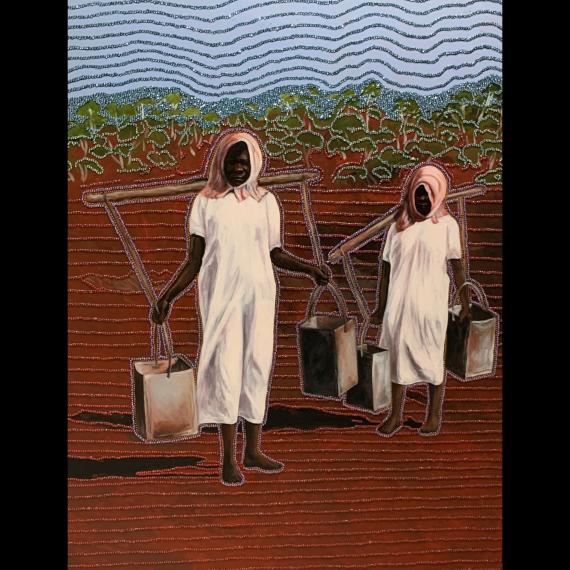

Join us for an insightful talk with the esteemed Professor Henry Skerritt, as he takes us on a journey exploring the captivating art of Jdewat/Ballandong artist Meeyakba Shane Pickett.

No, it’s not a card game but a community initiative helping us further our knowledge of a group of endemic land snails Bothriembryon affectionately called ‘Boths’.

Delve into the way Aboriginal industry professionals are shifting representations, decolonising the media space and creating visibility for Aboriginal people in the industry.

Exploring the debate surrounding the establishment of an independent, representative advisory body for First Nations people.

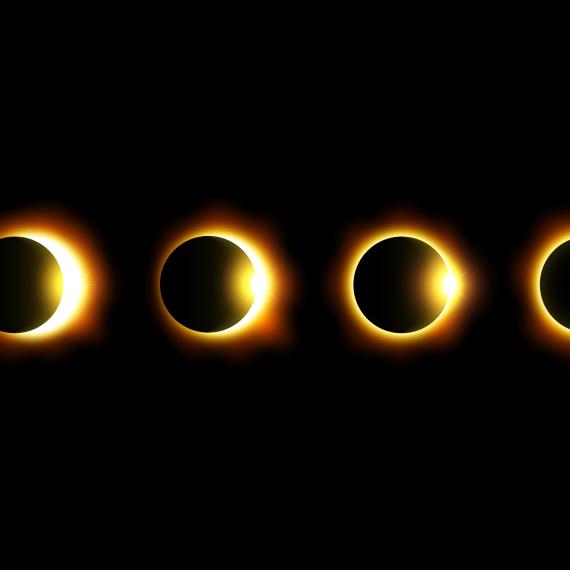

Aristeidis Voulgaris sharesstories from his eclipse chasing travels and discover the complex instruments and tools used in solar astronomy.

Join a panel of experts and community as they investigate the nature of queer bodies, and queer sexuality, in public space.

Join historian Toner Stevenson and astronomer Melissa Hulbert, as they share their tips on how to salute the sun during this eclipse!

Simon Miraudo and Tristan Fidler from RTRFM’s ‘Movie Squad’ are joined by Chelsey O'Brien, Curator at ACMI, as they review and discuss Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland as a foundation for contemporary storytelling in film.

In this one-off Perth Design Week talk, the Museum celebrates the remarkable women in architecture and film in a panel discussion, recorded as a part of its recent award-winning film screening.

Join world expert Dr Chris Mah from the Smithsonian Institution as he recounts his encounters with some of the most unusual creatures on the planet.