In Conversation: The Uluru Statement from the Heart

Why does Australia need a First Nations Voice in Parliament?

Change through action is needed to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to have a say in laws and policies that impact them, however, the debate around the details continues to create tension. As the referendum, inches closer, the people of Australia have been invited to start thinking about the decision they are going to make towards the constitutional recognition of a First Nations Voice in the Australian Constitution.

Join us for In Conversation as we explore the invitation of the Uluru Statement from the Heart, and hear from our expert panel as they delve into the principles around the establishment of Voice and why Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples need a First Nations Voice to Parliament.

Meet our Facilitator

Glen Kelly OAM is a Wardandi Noongar man from the south west of WA with 30 years’ experience in Aboriginal affairs and native title. Currently a Member of the National Native Title Tribunal, Glen served as CEO of the South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council (SWLASC), leading the development and negotiation of the South West native title settlement. Glen has played a prominent role in Aboriginal Affairs and native title across Australia, serving on a number of national and State boards and advisory roles. Glen was recognised as the Western Australian of the Year in the Aboriginal category in 2019.

Meet our speakers

Kyra Galante (Bonney) is a Guburn (Kupurn) woman from the Goldfields region of Western Australia, having connections to Noongar Country. Kyra has over 20 years’ experience delivering Indigenous community engagement, recruitment and mentoring strategies in civil construction and mining. In over two decades Kyra has increased Indigenous employment across those sectors through policy advice, program management, community engagement and candidate selection. Kyra’s recently undertaking a role as a WA Ambassador for the Yes Campaign.

Emeritus Professor Simon Forrest was born and raised in Wadjuk country. His mother is Nyungar and father is Yamaji, Wongutha. He trained as a primary school teacher and worked in schools in Aboriginal communities and rural towns in Western Australia. Simon is WA’s most established Aboriginal academic commencing in 1983. He was the first Aboriginal person in WA to be appointed to a Head of Department position at a university. He retired in December 2019 and in recognition of his contributions to reconciliation and teaching of Aboriginal studies and Aboriginal education at Curtin University, Western Australian and internationally he was awarded a Curtin University Fellow and Emeritus Professor status.

Emeritus Professor Colleen Hayward AM is a senior Noongar woman with extensive family links throughout the south-west of WA. She comes from a teaching family with her father having been the first Aboriginal teacher, and Principal, in WA. For more than 35 years, Colleen has provided significant input to policies and programs on a wide range of issues, reflecting the needs of minority groups at community, state and national levels. She has an extensive background in a range of areas including health, education, training, employment, housing, child protection, family & domestic violence, and law & justice as well as significant experience in policy and management.

Megan Krakouer is the Director, National Suicide Prevention and Trauma Recovery Project. Megan holds an LLB and this year was awarded Perth’s Citizen of the Year. Megan has also been involved in various human rights campaigns, the latest being the class action against Banksia Hill Detention Centre with class action specialist Levitt Robinson Lawyers – that is now in the Federal Court. Megan is dedicated to the plight of her people living below the Poverty Line and to those also in proximity to the Poverty Line. Megan is seasoned with expertise working among our most vulnerable First Nations families. She has contributed through knowmore Legal Service two and half years to the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, visiting 30 remote communities and 27 adult prisons. Megan has worked with the most marginalised and vulnerable in the community with issues including suicidality, deaths in custody, homelessness, child removals, domestic violence. She has long standing work within government and the private sector. Her philosophy is saving lives and improving life circumstances for all brothers and sisters.

About In Conversation

A safe house for difficult discussions. In Conversation presents passionate and thought-provoking public dialogues that tackle big issues and difficult questions featuring diverse perspectives and experiences. Panelists invited to speak at In Conversation represent their own unique thoughts, opinions and experiences.

Held monthly at the WA Museum Boola Bardip, in 2023 In Conversation will take different forms such as facilitated panel discussions, deep dive Q&As, performance lectures, screenings and more, covering a broad range of topics and ideas. For these monthly events, the Museum collaborates with a dynamic variety of presenting partners, co-curators and speakers, with additional special events featuring throughout the year. Join us as we explore big concepts of challenging and contended natures, led by some of WA’s most brilliant minds.

Listen to previous conversations now.

-

Episode transcript

In Conversation: The Uluru Statement from the Heart

Wednesday 24th May

Epoch Café, WA Museum Boola Bardip

Facilitator: Glen Kelly OAM

Welcome to Country: Betty Garlett

Speakers: Kyra Galante, Emeritus Professor Simon Forrest, Emeritus Professor Colleen Hayward AM

CM: Good evening, everybody. Thank you for coming tonight to In Conversation at WA Museum Boola Bardip. My name is Ciaran. I'm a creative producer here at the museum. I'd just like to start off tonight with an acknowledgment of the traditional custodians of the land on which we gather this evening, the Whadjuk Noongar people. I'd also like to extend an acknowledgment to any First Nations people joining us in the audience this evening, including anyone joining online.

Tonight is being live streamed and recorded as well. If anyone would like to access this session post event, it will be available after midday tomorrow on the museum website. Some housekeeping: bathrooms are just across the way behind the bar and in the unlikely event of an emergency, just follow the directions of our front of house staff.

If everyone could, please help me welcoming Betty Garlett for a Welcome to Country.

BG: Kaya everyone. My name is Betty Garlett, my maiden name is Collard, and I am one of the traditional owners, elders and custodians of the land. Today I would like to acknowledge elders past, present and emerging. I would also like to acknowledge the Whadjuk boordiyars, on whose land that we are meeting here this evening.

I pay my respects to all who are present here also. Yakai marmuns, yorgas and koolangkas. I've said hello ladies, gentlemen and children. Today we continue to acknowledge connection to the land, water and the culture. Wandjoo Noongar Boodja [pending translation]. Greetings from the Aboriginal custodians. We welcome all people here to the land of many. [pending translation]. I said, ‘over the green grass, the bobtail roams, and like the flight of the boomerang, the magpie flies across the river and feeds on the sweetness of the banksia’. When you go home this evening to your camping grounds, go slowly. So naatj nidja, what is this? This is the land of the crow and the cockatoo dreaming. [pending translation], the bad spirits to go away and calling the good spirits in.

I'd just like to say thanks to the museum for having me at the last minute to come and do the welcome, which I'm quite honoured to do. I just want to say I'm glad I'm here. My son whose about six foot three, he says, “Mum, are you a dwarf?”, so I like to tell that little joke! I'd also like to say that this always was and it always will be Aboriginal land. I'd like to acknowledge my boordiyars here, who will have a very good conversation with you. I thank you very much for having me here. Thanks.

CM: I’d like to introduce our facilitator for tonight, Glen Kelly, and I'll let Glen introduce the rest of the panel. Thank you, everyone, for being here tonight and for taking time out of your week. Glen Kelly is a Wardandi Noongar man from the south-west of WA, with 30 years experience in Aboriginal affairs and native title. He is currently a member of the National Native Title Tribunal. Glen has served as CEO of the South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council, leading the development and negotiation of the South West Native Title settlement. Glen has played a prominent role in Aboriginal affairs and native title across Australia, serving on a number of national and state boards and advisory roles. Glen was recognized as the Western Australian of the Year in the Aboriginal category in 2019. Thanks for facilitating tonight, Glen, and I'll hand over to you.

GK: Kaya wandjoo Boola Bardip nartj djiripin Whadjuk boordiyar, Whadjuk boordiyars, Nyoongar boordiyars. Baal Koolangka [pending translation] boodja. [pending translation] Wardandi Nyoongar. I come from Wardandi country, I’m a child of the big tree country in the Southwest, from the lower South West of WA. My role here tonight, I say i’m djiripin for boordiya here, which is not quite the true way of saying it, but its saying respect for our elder and thanking you for the welcome to country.

My role here this evening is to facilitate the conversation. We all know why we're here. We're here to have a discussion, to hear from these distinguished panellists on The Voice to Parliament and what it might mean, and to have some discussion once they've set their views out to the floor. I'll run the conversation once we get there, but I would encourage if I can that once we have an address from each of our panel members, that we have some discussion and have some questions, to make sure that we get really good value out of the evening. Just before I introduce them, though, I wanted to run over what the referendum question actually is and what the proposed change to the Constitution is as well.

The speakers, of course, will talk about things with deeper meaning than the words that are on this page. Nonetheless, it's probably useful to remind ourselves of what is actually being proposed. On referendum day, voters will be asked to vote yes or no on a single question subject to the Parliament's approval. The question on the ballot paper will be A proposed law to alter the Constitution to recognize the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voice. Do you approve this proposed alteration?.

The alteration will be this; Section 129 of the Constitution In recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Peoples of Australia, there shall be a body to be called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice may make representations to the Parliament and the Executive Government of the Commonwealth on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws with respect to matters relating to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice, including its composition, functions, powers and procedures. That's the full text of what's been proposed to be inserted into the Constitution. I'm not sure if everyone's familiar with the Constitution. It's quite surprising when people first get hold of it to see how extraordinarily small it is.

What I'll do now is introduce the speakers and perhaps I might, instead of introducing everyone, I might go one by one so that we can get the conversation rolling, if that's okay. First of all, Kyra Galante (Bonney) is a Kupurn woman from the Goldfields region of Western Australia, having connections to Nyoongar country. Kyra has over 20 years experience delivering Indigenous community engagement, recruitment and mentoring strategies in civil construction and mining. In over two decades, Kyra has increased Indigenous employment across those sectors through policy advice, program management, community engagement and candidate selection. Kyra has recently undertaken a role as the WA Ambassador for the Yes Campaign. I'll hand over to you.

KG: Thanks for the introduction. Every time you hear people talk about you, it still doesn't feel like it's you, it just feels really weird. I've been involved in the campaign since early last year, and one of the reasons I decided to come on board when I was approached by the campaign, is because of the work that I do in employment. Education plays an important role as well as health for our people to be able to get employment. I work with a lot of community members and stakeholders. Stakeholders could be job active providers or Aboriginal corporations wherever Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are on their database looking for work. A lot of these corporations also have training and development to help them to transition seamlessly into work.

A lot of the work that I've done has been through those pathways. However, a majority of those contracts are with mainstream companies, not indigenous companies. A lot of these mainstream companies do get contracts from government to help Indigenous people to get into employment, to help train them and develop them and help with making sure they've got literacy and numeracy to be able to get into employment and then come into the industries. I found that it was a struggle of having to always advocate for my people to get access to what they should be getting access to, which is what the contracts should do. Just for training, just for them to do a TAFE course or qualification, which is a requirement for them to go into the role with a lot of the companies. A lot of our people, even though they may not have worked, they may have been caring for family members for example, but they have transferable skills. Caring for someone, being able to look after them, take them to their doctor's appointments, to the hospital, whatever that might be, there's transferable skills there. Being able to highlight that on their CV’s, to help them to transition into employment for the roles, I just found that it was a constant struggle just trying to advocate with a lot of these mainstream contractors, just to get access to employment for our people.

We know that employment also increases quality of life. A lot of our people, if you look at the average Australian wage, are living in poverty in comparison to Australia being in the top ten wealthiest countries of the world because of the resources that come out of this country. Our people, who are the minority groups, are living in disadvantage. Our kids don't get equal access to education. Our people don't get equal access to health services or are experiencing racism or discrimination at a higher level. This then affects them having the right diagnosis. I've lost a lot of family members because they were misdiagnosed and they should have been caught in the early stages to get the same treatment as everybody else, but that has not happened.

So just a little bit about understanding the journey that we're on here, this journey of our people, our ancestors asking for a voice for Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people isn’t the first ask. This has been ongoing for four decades. There is a history here in this country. The difference between asking for the Voice this time, is that we're not asking government because all we’re asking is to give us that voice because we know what the solutions are for our people. Having our input and being engaged, we know what works around policies and laws that will deliver effective services to our people on the ground. If there’s one thing that I want you all to take away here tonight, it’s that we are the people from your community. We've got vast knowledge and experience of working with our people. That's been all part of our journey, it's our lived experience. Open your hearts and open your minds to ask the questions, to be well informed of what you need to know. To feel comfortable, to listen to us and vote for the voice of our people in our communities.

I'll let Colleen or Simon talk about a bit more in depths around the Uluru (Statement from the Heart), but if we were to get the voice, what would that look like? We will, first of all, get acknowledged and recognized in our rightful place in our own country, which is important. It says that Australian people do acknowledge us, recognize us, but we're able to walk together as one nation and celebrate this country to what we know it could be for us and for future generations. Not just our children, but all of your children and grandchildren who are going to carry it forward. What we're asking for is really, really important.

The reason why putting us in the Constitution, besides acknowledging and recognizing us, is also making sure that when we get that voice to Parliament, it doesn't matter which government comes into play, they can never remove that voice. We know, that to have an impact in changing a lot of the disadvantage of our people is going to take time, it's not going to happen overnight, but we can be guaranteed to see the impacts of that over the next decades and generations moving forward. To know that they're still going to work on what those policies and laws are, and improving the quality of our young people's lives, our people's lives and elders lives, so that we could actually live a long life just like our Australian brothers and sisters, because that's not the case today. I might just hand it over to Colleen.

GK: I'll introduce Colleen. Emeritus Professor Colleen Haywood AM is a senior Nyoongar woman with extensive family links throughout the south west of WA. She comes from a teaching family with her father having been the first Aboriginal teacher and principal in WA. For more than 35 years, Colleen has provided significant input to policies and programs on a wide range of issues, reflecting the needs of minority groups at community, state and national levels.

She has an extensive background in a range of areas; including health, education, training, employment, housing, child protection, family and domestic violence, as well as law and justice. In addition to significant experience in policy and management. Colleen.

CH: Thank you, Glen and thank you, everyone. Usually in these conversations, I find it quite useful to share with people how the Uluru Statement actually came about. I do that because of almost a vacuum in the knowledge around that and coming from that, an inability to counter the untruths that have been told about it. Several years ago across the country there were a series of regional dialogues, that's what they were all called. In Western Australia we had two, essentially dividing the state in half, so there was one for the bottom half of the state and the top half of the state. In each of the regional dialogs, not only in WA but across the board, there were 100 delegates. Of those hundred, sixty were nominated by the local Aboriginal Land and Sea Councils. The majority focused on traditional owners who could speak for country. A further twenty were nominated by key Aboriginal organizations, legal services, medical services and the like. There were a final twenty that came from people in academia, corporate and other places who might not have been nominated through an organization or the Land Council, but nevertheless it was important to have them and their views in the room. So it was really representative, and had a focus on traditional owners and who could speak for country.

We workshopped for three days solid with lots of people. We've talked about the Constitution, most people haven't seen it. They don't know how small it is. Many have never voted in a referendum, and one of the questions that I've been asked lately in terms of whether or not corporates come on board and make a statement is, well, they really backed the same sex marriage in that plebiscite. Shouldn't they come on board now? What people don’t recognize, is that there's a big difference between a plebiscite and a referendum.

We're not well informed as a community. We're not well informed about our legal processes. A lot of that workshopping was about that. If we say we want a change to the Constitution, what the hell does that mean? What does it mean when you have a referendum? Within that context, how can things be taken forward? We had a look at the struggle, for decades. In fact close to 100 years worth of formal requests from various people, various native title groups, nations across this country that were seeking something better from government, that were seeking a voice. A voice, I might add, is really what we all want, not just in this context. To me, if we strip it all back away from the complexity, if something's going to impact on us, do we want to be consulted? Do we want our views known before the decision is made? Well, you know, actually we do. That's kind of what we all want. That's what this is about.

From each of the regional dialogues, people were elected. Twenty from each of the dialogues went to Uluru to workshop once again, taking the views from their region there. Once again, it was very representative. I want to dispel a couple of untruths. I've heard several different people say, “the people who were at Uluru, more than 60% of them weren't even indigenous”. That's not just an untruth, it's an out and out lie. Everyone there was Indigenous, and they were elected and they were represented to speak from their dialogue and to speak for country. One of the other untruths coming from that national convention where the Uluru Statement was formulated, was that there was a ‘mass walkout’. I'm never sure how you can use figures to explain that maybe ten people out of 250 leaving a room is somehow mass. That's all it was, a handful of people who didn't get their way. That is not what's been portrayed in some media coverage. One of my nephews was there and remains irate, because he saw himself in this apparent walkout. I might add it was the end of the day and he was heading to the dinner line, as were we all! That’s how that misrepresentation grew legs.

It was representative. It was informed. It was damn hard work and it was collective with leadership from those who could speak for country. That's a pretty damn good thing to support. On the question of ‘why can't we do that now?’, ‘Why do we need constitutional recognition or constitutional change?’. A, It’s a long time coming and B, we used to have that until the Prime Minister of the day decided we wouldn't and put a line through it. If it is not in the Constitution, there is no safety for people going forward. They’re the comments I'd like to make, Glen, just to get us started. Thank you.

GK: Emeritus Professor Simon Forest was born and raised in Wadjuk country. His mother is Nyoongar and his father is Yamatji Wongatha. He trained as a primary school teacher and worked in schools in Aboriginal communities and rural towns in Western Australia. Simon is WA’s most established Aboriginal academic, commencing in 1983. He was the first Aboriginal person in WA to be appointed to a head of department position at a university. He retired in December 2019 and in recognition of his contributions to reconciliation and teaching of Aboriginal Studies and Aboriginal Education at Curtin University, Western Australia and internationally, he was awarded a Curtin University Fellow and Emeritus Professor status. Simon.

SF: Thank you, Glen and kaya everybody. So, before I start, there's only two Aboriginal Emeritus Professors in this state, and they’re sitting right here. Colleen, correct me if I'm wrong, it's our first gig together as emeritus professors. If everything was equal in terms of our participation in the community, there would be at least 20 Emeritus Professors that were Aboriginal. No, there's only two.

Let me start in terms of the Voice. I believe the referendum is a most important point in our nation's history, a really, really important and significant time. However Aboriginal people vote, and we might vote as a bloc, all of us across Australia, 300 to 400,000 people, if we all voted yes, that would make no difference to the outcome of the referendum. It's entirely up to the non-Aboriginal population to decide our fate once again and hopefully for the last time. So it's a really, really important thing.

When Anthony Albanese made his victory speech after the election in May last year, I think Ronnie, my wife, was in tears watching him and I was jumping up and down, “What can I do? What can I do? I need to do something now. I can't just keep sitting around!”. So I put it out there to people that I was willing to go and talk to whoever I could about the Uluru statement from the Heart, including the welcomes that I do. I included bits of information about Uluru since it came out in 2017 in all of my welcomes, and since May last year, it's been in a bit more detail. So I kept a count and it's around near 30,000 people I've spoken to since May last year, including year 12’s, community groups who have contacted me, a company of electricians I think they were. Everyday Australians contacted me to come and talk about the Voice. It's not just talking about the Voice, I put it out there that I'm an advocate for ‘Yes’. So if you want someone to give an alternative view or a ‘no’ view you need to go and find someone else. A couple of government departments engaged me to come and talk. Their senior Aboriginal person engaged me to come and talk to their staff about the Voice, but I got a cancellation from the Director General for me to come and talk about the Voice to staff in a government department.

So I started yarning to groups of people, the most recent one was at Scotch College to all the year 12 boys, last week I think it was. About 50 percent of those boys will be voting for the very first time at the referendum. So I asked for a show of hands “who's 18 and who's going to register to vote and who's going to be voting in the referendum in October?” About 50 percent put their hand up. I said you’re voting in one of the most important times in our nation's history.

So when I started talking, I developed this PowerPoint, as you do in academia, about ten slides or something, but I don't use that anymore. I use about one or two slides from that PowerPoint and I carry around two things, three things, actually. One is the Constitution, this is what it's all about. We talked about how small it is. The body of this constitution is 30 pages long, 128 sections in 30 pages. It's dated, it's got my name and its got ‘1976’. I knew it would come in handy at some stage (laughs). I use a couple of passages in it. What's really good about it being from 1976, it actually shows in the text the wording prior to the 1967 referendum and then what happened to that text, and I'll refer to it later in terms of that change.

The other piece of paper that I use, in terms of what's led up to this event, are all these sorts of things that have happened in our community. I don't include things like Mabo or reconciliation, I refer to things that are directly related to the outcome of this referendum. Oddly enough, it starts in 1901 with the Constitution. One of the first questions I ask groups of people is “hands up those that have read the Uluru Statement from the Heart”, and it's generally around 10 to 15 percent of the audience that raises their hands.

CH: I think you should ask them!

SF: Hands up if you've read the Uluru Statement. Well, that's a bit more than 10 percent. Interestingly enough, going to schools, that's where you get more than 10 percent put up their hands. Then I ask how many times have you read it? Twice? Have you read it more than five times? Generally there's no hands up. So hands up if you read it more than five times. If you're voting, and it's going to be non-Aboriginal people that determine the outcome of this referendum, you need to know what's in there, what you're voting about.

This other sheet of paper, giving these sort of dates and things that happened. One thing I've got is Article 19 of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People, where Australia was the last country to sign and endorse. Article 19 states that nation states shall consult and co-operate in good faith with Indigenous peoples concerned through their own representative institutions, in order to obtain their free, prior and informed consent before adopting and implementing legislative or administrative measures that may affect them. That's the Voice. It's clearly the Voice.

The other main point that Glen read out, the question and a couple of additions on it, I refer to Section 51 of the Constitution has all the powers of the Commonwealth, so when the Commonwealth of Australia was created, the states or the colonies got together and said these will be the Commonwealth powers and there’s thirty nine. Thirty nine powers, all of them are one sentence or less. Some are one word. Everything that the Commonwealth had responsibility for in Covid-19 for three years was based on one word; quarantine. That's section 51, subsection nine. You’ve got census and statistics, two words. Naturalization and aliens, two words. Marriage, one word. Divorce is a few more words… about ten (laughs). But marriage is one word. Invalid and old age pensions, external affairs, and the rest of them are three, four, or one sentence long. There is no detail. The detail of these powers are left up to the Commonwealth.

What are we voting for? You’re voting on a principle. All this is, is a set of principles and guidelines for how governments and democracies are to operate in the Commonwealth of Australia. That's all it is. A set of guidelines or principles. So the Voice is about voting on a principle; yes or no. The detail comes later. There's no detail in this thing, otherwise it'd be 10,000 pages long. There is no detail. There's no detail in defence, which is about three or four words, no detail in there about $10 billion submarines. That detail comes later. So we're voting on a principle. I add to that, that we vote on a principle of First Nations voice to the parliament. Yes or no? Do you agree to that principle? Then I add to that a value proposition. And the values proposition is, is it the right thing to do to give First Nations people a voice or is it the wrong thing to do?

GK: Okay, before we go into open discussion, do any of the panellists have anything they'd like to add, considering the words? Do you have anything more that you'd like to say, considering the round of conversation.

KG: I'd just add that the Uluru Statement of the Heart that’s coming from our people, nationally across all parts of Australia and the Torres Strait is a gift to all of you here. That's an amazing thing. If you get the chance and you haven't read it, read it. It's a gift. We're extending the invitation to all of you here today to understand who we are, our ancestors, our connections, our ties to this land that all of you are now tied to. This is your country. We're all part of you. You're all part of us. If there's one thing that each and every one of you can do is now we need your voice. That's all I'd like to say. Think about that.

GK: Okay. I might stand down here so I'm not in the way of the panellists. They're the Main show, not me. We'll open to a discussion, I think it's really worthwhile. We've got the opportunity to really work into the soul of this, into the heart of it, you know, we've covered a variety of topics, I’ve read the questionnaire and all of that sort of stuff, but there's more to it. There's a heart and soul of this thing, to invite all sorts of different views and to say that we'll be respectful of all sorts of different views. Whether you support this idea or not, it's a good opportunity to discuss those things deeper, or to raise doubts or seek clarifications if you would like them, given that we have a really esteemed panel in front of us. It's a really useful forum through which we can have a conversation like that.

Is there anyone who would like to make a comment or anyone who has a personal comment or something that they'd like to express in relation to this proposal overall, irrespective of whether it might be a question?

Audience Member 1: I'd like to talk to the point that was very important to bring up. I understand the difference between a plebiscite and a referendum, and legally, that means everyone has to vote. My big concern was for the plebiscite. Being a queer person, it was very difficult to tolerate and understand the idea that the majority of the population was voting on my right or privilege to be married or not, and what if they voted no? In my ideal world, only queer people should have been voting in the plebiscite for marriage equity, because that's just us defining what we want, what we need, and how we want our future to be. It felt very dangerous and risky to have the majority of the population, who are not queer, voting and 35% of people did vote no and that was really damaging as well. To think about that, and the arguments that we had to listen to and tolerate, it was very tough. I feel for the Aboriginal people now that again they're in that situation, where the majority of the population are deciding their fate. For me that feels very helpless and very unfair. I just want to acknowledge that.

GK: It's a pretty poignant comment.

SF: We want it in the Constitution, and Colleen mentioned something before about there having been two Voices previously. In 1973 or 1974, Gough Whitlam set up the National Aboriginal Conference, a voice, and then ten years later in ‘85, Hawke got rid of it. Same political persuasion, but he got rid of it. Maybe he had other ideas in play by developing ATSIC a number of years later, another Voice, through legislation creating the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission. Which was more than a Voice, and did a lot of other things more than a Voice. Then Howard disbands it! He didn't like what was happening and there were certain things around fraud and dodgy things, but Medicare is going through the same thing, look at robodebt! It's not disbanded. They make it better. Why didn't they do that to ATSIC? No, they just got rid of it. So those legislative voices are at the whim of government. One government giveth, another government taketh away. So the only way to get it there on a permanent basis is through the Constitution, and that's a risk we have to take.

I've been asked about if there's a no vote, my first reactions were, I don't even want to contemplate a no vote, which is really hard to do at the moment. What am I going to do? Well, I've got a few things that I'll do. The recent treatment of Stan Grant brought that forward. All the openly racist remarks towards Stan Grant, they're all the no voters, I would have thought. I know what I'm going to do if a no happens. But I'm very hopeful that a yes will happen. It has to happen.

CH: I think for me, I've been in the same boat. Without having a plan to go forward, I just don't yet want to contemplate that the answer might be no. I empathize because the situation is very similar in terms of others deciding the fate of. That's the system in which we're caught, quite frankly. I think for me, as Simon was running through the ‘who were players in terms of establishment and then dissolution’, no major political party is exempt. For too long Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander affairs have been a political football. My recollection, hopefully correct still, at the time when ATSIC was disbanded Mark Latham, of all people, was the leader of the Labor Party, leader of the Opposition, and came out and said “if we get elected I’ll disband ATSIC”, like that's supposed to win your vote. To which Howard responded, “Well, I am Prime Minister, I'll do it now”. Not ‘this isn't happening, this can be made better’, no - political football. It's not how this country should run. It's no indicator of maturity as a nation. That is what we've got to get to. To me, this is an important step on that journey.

KG: I'll just add on the back of Colleen and Simon, that this is to the Australian people. We're not asking the government. There's a reason why we're asking you, because in the past all those asks to government have not worked for four decades. We're constantly having to bury our people young, way before their time. So we're constantly grieving. We're living in a world of grief. We don't even have time to grieve for one person when another one in our community passes away.

You talk about wealth creation, people have opportunities before us. We're trying to do catch up. That's why myself and others are in roles of academics to help our mob get the qualifications needed to get into employment and create wealth. These are all the flow on effects that are not happening. As a matter of fact, the latest data says that Australian people's quality of life is increasing, and so we’re falling further behind. If you know how much a funeral costs to bury one person, we're constantly having to bury our people. All our money is having to chip in to Go Fund Me pages to help us bury our loved ones.

This could not be the country of the fair, because that's not the lived experiences of us. We’re the minority, we’re the First Nations people. We extend our culture to you. We are the oldest living culture in the world. This is what you get to celebrate. This is something you take to the platform as Australian people. We're not asking a big ask, but the impacts that it has is in your hands. That's the power you all hold here, not just with yourselves, but with your families and your community, anyone within your sphere of reach. That's all we're asking. Help us, so that we can help our people and not have to be that country.

GK: Okay. Yes. There’s a question over here, so we'll just need to get you the microphone. Thank you

Audience Member 2: I was just wondering if it was possible to read out the Uluru Statement? To be able to understand how did the concept of the Voice come from the Uluru Statement?

SF: Well, what I normally do when I give my sessions, I get five people up the front to read a paragraph or so each of the Uluru Statement. I'm not sure that will help. If you've read it, that's good. If you haven't read it, maybe you should go away and read it and listen to other people here because it actually says there that we need constitutional reform and a voice, that's there! I would suggest we leave that for the last thing, for a group of people. I carry around five Uluru Statements from the Heart here, I give them to one person each to read through it and it's a good ending. That would be my suggestion.

CH: Can I add, that as well as the statement, you'll know that the three words; voice treaty truth, came from that national convention. There was a whole lot of dialogue, once again over days, about the order of those three words. We know that some of the opinions that have come back from Indigenous people have been, “I don't want to vote yes, because I think we should go for a treaty first”, so some of the objection, if you like, is about that ordering, though the order itself was decided by that democratic process. I must also say from a personal perspective, if you were going for a treaty, I would think it'd be a hell of a lot easier if you had a Voice with which to develop the treaty. That's just how my brain works.

GK: Or indeed, that a voice would be a natural result of a treaty.

CH: But yes, strongly debated.

GK: Okay. Yes.

Audience Member 3: A couple of words were taken from the statement tonight. ‘Gift’ was the one that sort of resounds. The section where they talk about the children, so our children walk in two worlds and their culture will be a gift to this nation. That's one of the ones where I'm talking to colleagues and people I encounter every day. I wonder if we can get our esteemed panel to talk on that concept of giving? This culture and the absorption of this gift into, I guess, the mainstream society we live in. What would that look like, particularly on behalf of our children as they give it forth. This unique ability to appreciate the land beneath our feet, in the sky, above our head, and the unique way that we love, and all that sort of stuff.

I wonder if I can get our panel to maybe comment on that. What that gift notion would be like.

SF: I've had four experiences internationally where other First Nations have actually said it or through their actions. I’m talking about Ainu in Japan, Sami in Norway and various groups in North America and South America, They refer to us Aboriginal Australians as the first of the first people. All the first Nations people around the world refer to us as the first. If you take that a step further, that's the first born of all peoples, first born of all modern human beings on this planet is us. From that, that's where the statement about the oldest continuous knowledge system on this planet comes from. That's us.

Internationally, other First Nations people recognize and see that, but that doesn't happen in our own nation. It is a gift. Our gift is that we are the first. Our culture has evolved here in Whadjuk Noongar boodja for 40,000 years, and is still here. That's our gift to the people. All that knowledge, all that information, how we work with the environment, all those things are a gift. I just can't keep saying that other First Nations people recognize and acknowledge that, but we're still in a situation of actually saying to us mob, first people, “oh we don't know if we’re going to give you a voice or not”. We aren't even at that stage to recognize and acknowledge our gift to the nation, we aren't even there yet. Hopefully the outcome in October might suggest otherwise.

CH: If I could add to that, I know that there are varying ‘guesstimates’ about our longevity. There is some research now in Western Victoria that suggests up to 120 thousand years established they I can prove. I find it interesting if we just, for the purposes of round figures and ease of reference, if we take 60,000 years and liken it to a clock. On the 12 hour clock, each minute is a thousand years. Western Australia hasn't had its bicentenary yet, so non-Indigenous Australians have been in Western Australia for a fifth of a minute. We're talking seconds! It's nowhere near a minute. Surely for the rest of those tens of thousands of years, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people must have got something right. That's part of the gift. That's what Simon is talking about. We heard about it a couple of years ago with massive bushfires down the east coast of Australia and then in the south west. “Oh gee, maybe Aboriginal people know something about fire management, Maybe there's something we could learn here”. It almost takes a catastrophe before people recognize that their practices can be informed by ours.

That's what we want to give. It's what we want to share. And for the general conversation, not related to this, but about ‘what is Australian society?’, ‘what are our values?’, you know, those sorts of conversations. I remember a couple of years ago someone saying to me, “what is unique about Australia?” and the answer is, us. We're the bit that's unique, and we want to partner. This is about letting us, and providing the facility to enable it.

GK: I have a question of my own, if that's okay. The proposition for The Voice has invoked a response amongst the broader population. There are many people who may support it and there are many people who don't. One of the arguments that I've heard come forward is that, if we provide this special measure for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, we're dividing the nation on racial lines. The philosophy being that this is one nation of people which is not segmented, so therefore a special measure shouldn't be required or isn't in any way warranted.

What would your response to that type of argument that's revolving around the country be?

CH: This is being recorded, and we have to be careful with our language? Okay (laughs), I'll let Simon go first.

SF: Thanks, Colleen. It’s a really interesting question. If you look at the Constitution, I’m quoting the Constitution back to section 51, subsection 26. Prior to 1967 referendum it stated this: The people of any race, other than the Aboriginal race in any state for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws. Race is already in the Constitution! It’s there, it's black and white. What that meant was that the states had the power to make laws for Aboriginal people. They made laws about taking children away, they made racist and restrictive legislation in what we could do, where we could go in and around the city, of who we could marry. They were all the states that created those laws, and the 1967 referendum struck out these words; other than the Aboriginal race in any state. What that enabled was the Commonwealth to make special laws for Aboriginal people and the people of any race. Race is already in our constitution, so don't bring forward this idea about race and separation. We didn't start that, whitefellas did. Whitefellas invented the concept of race. Whitefellas, in terms of Western European countries, developed the concept of race as a scientific sort of concept, which has since been debunked. That was about power. Power of Western Europeans over others, people of color. People of Asian and Middle Eastern descent or look, and it's reflected in our Constitution about power. That's what it's about. They are totally false misinformation and misguided arguments to misinform people. What do people do if they're misinformed? They're more likely to vote no.

CH: I think Glen and Kyra have alluded to this, especially in her introductory comments, that every state as well as the Commonwealth have equal opportunity legislation that in part recognises that not everyone is treated the same or treated fairly. There’s the equitability argument. I must say that (in the creation of) the Constitution, all blokes. Not just white, but all blokes, because women weren't allowed then either! There is a whole lot of stuff that we don't consider.

To put it into context, some of Simon's comments about how wrong the states can get things over time. Being the age that I am, I well remember the demos and marches against apartheid in South Africa. Some of you will remember, or have also been involved. The story that is not told in Australia, is that before apartheid legislation was introduced in South Africa, government officials from South Africa came to Australia to find out how to do it. The two states they took most from were Queensland and Western Australia. This has not been an even playing field for a very long time. This is part of getting it to that point where everyone not only can belong, but knows that they belong.

KG: I just want to add on to both Simon and Colleen's comments. In that time and era of the Constitution being put together, it had been designed and engineered to exclude people of other races, and to actually control those coming into this country, including controlling us. Just to give people a bit of understanding of what that felt like, when COVID came to Australia, laws were put in place all over this country. The effects that it had on people such as where they can go, whether they work, what they can do, if they can travel, if they can see their loved ones, if they can attend funerals. We're still dealing with the mental emotional effects of that today. Imagine having that for 250 years of your life, because that's the life that our people live.

Audience Member 4: Thank you. Glen, you sort of started my question a bit more eloquently than I probably would have phrased it, but I take it from this audience, without wanting to put words in people's mouths, that most of us are convinced. Presumably our job when we walk away from here, is to help people we know understand this better and perhaps give them some simple messages about why they should vote yes. It's obvious to me, but I'd be keen on understanding from your travels and from your advocacy, what arguments you're hearing from people who might be on the fence like us. How may we be easily able to overcome those with some simple messages?

It’s so easy for me, this is not something I have to get my head around, but I will probably know people who don't know enough about it, or who don't know quite know what they're not overly convinced about. Can you help us with those messages?

CH: I don't know if I can help. I say that because some of my comments this evening, I've tried to dispel some of the untruths, through to out and out lies. I think we all have in our commentary. I'm getting really weary of the “oh I don’t know”, “oh, there's not enough detail”. There are so many places that you can go to on ‘Dr. Google’ to find out what it means. Right now, I want people to know, and actually take a stand enough to go and find out. Instead of sitting back and waiting for the information to come to them. It's time. It’s actually time for people to take a stand and ensure for themselves that they are informed enough to vote properly. Regardless of which way, be informed enough to vote properly, but don't sit back and ask to be spoon fed. I'm over that.

KG: I will give you some of the resources (audience laughs). We have the Uluru Statement from the Heart website.

They have plenty of resources on there, information fliers. We also have ‘Yes 23’. So sign up, volunteer. You will get real information from both of those places in real time. It'll have fliers, so you can go out and you can engage. It’s just simple language that's used on what this actually is. It’s not complex or anything. If you sign up with the ‘Yes 23’ site, you will be part of organizing a Day of Coming Together for Yes, which is 2nd of July, to celebrate the up and coming referendum. There'll be a lot more information around the tools that you will need to do that, to participate and engage and share that with everyone throughout Australia.

They're the main two sites. There's also another site called ‘Together Yes’. Go on there. They are hosting events all around Australia, I believe it's here in Fremantle, face to face and online. Reconciliation WA, have free online zoom events that you can attend. It's free for all Australians who want to inform themselves, be able to feel confident, to go out and have conversations that are so simple really. I believe we're an intelligent race here, you know, in Australia. It's so simple and anyone can do it. They're the main ones.

SF: While in my yarns with people, that's what the 20 Powerpoint slides were about, you know, “go and see this site, this site”, but it's changed because it's about amending our Constitution, which is a set of principles. All that is required is a yes or no. All the detail, the 200 page report by Marcia Langdon, it's all there. People can access it if they want. The prime thing is, voting on a principle. Yes or no to a First Nations voice. Once again its that values-based proposition. Is it the right thing to do to give our First Nations people a voice or is it the wrong thing to do? I would challenge people who say it's the wrong thing to do.

I think it was mentioned earlier about all the corporations. I think the Dockers did it today. I'm a West Coast Eagles supporter, we did it a couple of weeks ago and beat you mob.

CH: That was only to divert from the losses! (laughs)

SF: Thanks Colleen! I spoke to a CEO of another organization, who have put it out there about supporting a voice as it aligns with their values around equity, around respect, around reciprocity. I ask you how many organizations have come out, and not supported it publicly and said that. How many have said no? The only organizations or groups are the Liberal Party and the National Party. The conservative side of politics are misinforming you. They're telling outright untruths to misinform you to create confusion. If people are confused, if we go back to the republic (referendum), are you going to vote no?

It's up to us to tell you that you're being misinformed. It's a political strategy. The whole issue is political. Colleen talked about a ‘political football’. When you think of the leaders of the government, if he gets a yes, he’ll be a hero of the world, or of Australia. If the Leader of the Opposition gets the no vote, he'll be the hero of Australia. It's all these political things coming into play, but it's about us First Nations people asking you non-First Nations people to give us a voice.

GK: Yes. Question

Audience Member 5: Can you share any other jurisdictions or countries where a model like The Voice has taken place and tell us a little bit about what has changed and what's happened in those settings?

SF: In Canada, the Inuit have their own state. They govern their own state, province or whatever they call it in Canada. The Sami people have their own parliament, as a voice. They can't make laws for the Finnish or Danish government, but they have a parliament and they've got buildings and representatives and all that to provide a voice to the Finnish and Danish parliament about issues that affect them. It's in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Why haven't we done it? The Maori, they did it way back when in the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi a couple of hundred years ago, that's their voice. They've always had it. Why has it taken us so long, still us asking you to give us a voice?

GK: Yeah. The Maori having dedicated seats in parliament

SF: Yeah, as part of the treaty.

CH: Yeah, I should say too, “Oh no, we don't need a voice! Look at how many Aboriginal Torres Strait Islander people are in Parliament right now”. That's one of the arguments. However, for too long and most often, there's either been not one Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person or only one. Right now there are more, and that's fantastic. Come the next election we might go back to zero and that's a chance. This takes us beyond that. In New Zealand, (Maori) have designated seats as Simon and Glenn have alluded to. That is not to say that Maori can't stand for other seats as well, but that voice through the designated seats is guaranteed no matter what else happens. This (The Voice) is a guarantee through the Constitution.

KG: Just to go on from what Colleen’s saying about don't be confused about our Aboriginal politicians. They represent their parties. We know what that looks like. As an example, Ken Wyatt. He was in his party, but when this didn't come through it didn’t align with his personal values, because he did play a role in the Voice in the beginning. The voice came about when the Liberals were in, so it was liberal for quite some time before we came into Labor. Labor have executed now on that promise to the Uluru Statement of the Heart on the back end that was started with the Liberals. Don't be confused about what you hear and what you see through the media.

There’s another industry that I talk a lot about, because that's the space I work in, that not many people actually know or hear about. It's called the Aboriginal industry. It's a money making business and there's a lot of companies that are profiting of our disadvantage. I'll talk about prisons; our children being incarcerated, our women being incarcerated, our men being incarcerated. They're all privatised companies. The people who are funding that, I wonder who's behind that door.

Audience Member 6: Thank you so much for what you've presented so far. It's been really enlightening. I come from a rural town that's quite conservative and this issue has become so contentious that it's actually a banned topic of conversation on our local social media pages.

I guess my question is, how do we support the Aboriginal people within our communities in the lead up to the referendum? I'm concerned that advocating, and going onto the websites and getting the brochures and doing that sort of work in the community, might open up some really awful rhetoric that I feel could be quite damaging.

How do we do the work in promoting the Voice without causing more harm?

CH: I'm not sure that there's an easy answer to that. I think we've seen high profile cases like Stan Grant, taking a conscious and deliberate step back from all the racist comments that have been thrown in his direction. I don't know about you guys, but I'm seeing so much more of it. Talk about people, cockroaches coming up through the floorboards. It has given license to people with negative views, that all of a sudden it's okay to portray what those horrible things are. It's one of the reasons why I ignore social media. It's so damaging to people's psyche, and not just as individuals, but our whole society. Lots of that stuff should never be said. It shouldn't even be thought, but it definitely shouldn't be said. I think the quiet support of Aboriginal people in your community, from the more people, the better. Trust me, they're going to know about those comments, they're going to be internalising it, it's going to be eating at their souls and they will need support.

SF: I think in this country town, and I've taught in some country towns and things like that, I think if this was happening way back then (laughs)… You've got to be careful yourself in terms of giving out those messages. Sometimes I challenge students that I teach about this information, but do you sit at a barbecue and let those comments go by or do you challenge people? I think you've got to be aware of how much information you have to challenge people who say the wrong thing, and are you willing to do that? You've got to pick your fights and if it’s going to cause you serious harm, then don’t worry about challenging that person or persons. But I think an effort is worthwhile in taking some of this information you may have heard from me around the values proposition of ‘is that the right thing to do or is the wrong thing to do?’.

You get the conservatives and Leader of the Opposition saying that its bringing in these issues of race and it's going to create this division in our society. Well, the Solicitor General of Australia, who provides legal advice to the Government and the Parliament, he stated that this will enhance our democracy and make it better. Which is contrary to what the Conservatives are saying, but this is a top legal officer in our country. Even the former Chief Justice of the High Court, Bob French, talks about high return, low risk. For me, its about highlighting those messages that are incorrect. Whether people are saying that in a strategic way, or whether they're misinformed themselves, to me they're purposeful. If we're going to have a no, what's that saying to us? That’s saying from the non-Aboriginal population, “we don't trust you, we don't believe you, we don't think you should have control over your own affairs. We non-Aboriginal people will make that judgment.”. That's what they're saying, is that they don't believe us or trust us. To me, that’s the messages around, again, how you pick those times to speak up. You've got to be careful yourself too.

KG: Just to add on the back of what Simon saying. When you hear people talk where they're misleading Australian people, listen to whether its factual, do they talk about facts? First of all, because we know we talk about facts. We've got more than enough research out there demonstrating those facts. We have a history here where we've asked for this for more than four decades. That is fact. So when they talk, do they talk about facts, or do they keep it very generalized? We're all coming from a fact base of truth, and we have reasons behind that as to why we want this to change. Do they give reasons?

To answer your question, some of the stuff I do is I don't go on social media. I have friends check in on me, to make me feel supported. They are Australian people, friends, just saying, “how are you? How's everything going”. But I know that I'm responsible for managing my own mental health. I connect with country. I go off the grid, because all of that noise out there I know is not good for me. That's not the stuff I'm focusing on. All I'm focusing on is what I'm doing and making sure that I'm informing our people, in our communities and Australian people with the facts and giving the reasons why.

Audience Member 6: Thank you

CH: I do want to reinforce Simon's comment about making sure that you're safe in terms of any challenge. I think for me, in any debate, take this question and take the referendum out of the equation, there is still too much racism within our communities. I always reference the backyard barbecue because somehow that's where it all happens. Always make sure that you are safe, always make sure that you are supported. So long as you are, you don't have to have an out and out argument. It's okay to quietly say to someone, “I have a different view or I'm not comfortable with you expressing that view in front of me”. I think its about the words that you use, so that you can challenge honestly, but not in a way that puts you in the firing line. That is my advice on everything to do with race and racism.

GK: We might have time for one last question. Nope. Okay. I might do a little summary if I can then, and then as a as a last action, we’ll read the Uluru Statement. I won't pick people from random, you can self nominate.

I think just reflecting on the conversation over the last hour and a half, it's been it's been sort of interesting in a way that the conversation has run and the types of things that have been said. I just wanted to reflect on that for a minute. First of all, we've heard from the panel a fair amount of information about the Constitution. The fact that Aboriginal people were never involved in its development. The body of oppressive laws that it allowed because it kept that responsibility to the states. The lack of ability or agency that Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islander people have had in laws that affect people's lives throughout history. They’re all really important things, but they're not what I want to highlight.

My observation, is that we're here talking about the Constitution and laws and various different things, but I guess in the same way as that original question, what we've heard is a lot of heart and a lot of feeling. This is quite different, I think, from a normal discussion that you might get out of a law or a change in the Constitution. I think what that does is show that there is, in a similar way to what you expressed earlier, more meaning here than perhaps a dry, simple legal change. I think that deeper meaning was explained by the panel as we've gone through. Given the lack of agency around laws and that systematic oppression through the generations which we all feel, and we all understand.

I just wanted to reflect on that point, that while we're talking about something, you know, the Constitution and voting and yada, yada, yada, what's actually been conveyed in addition to that is this depth of feeling which is derived from something quite deep and intergenerational. Whether you felt that, whether you recognized that along the way, whether it makes any difference now, I don't know. It may, or may not, but I just wanted to highlight that there's deeper significance here for the people that it impacts upon.

Now, The Uluru Statement. Who are our five people?

SF: Get six.

GK: Ok six people. I think there are six people

Six audience members enter the stage

Audience Member 1: Thank you panel. It was and it's just great be here.

Our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tribes were the first sovereign Nations of the Australian continent and its adjacent islands, and possessed it under our own laws and customs. This our ancestors did, according to the reckoning of our culture, from the Creation, according to the common law from ‘time immemorial’, and according to science more than 60,000 years ago.

Audience Member 7: This sovereignty is a spiritual notion: the ancestral tie between the land, or ‘mother nature’, and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who were born therefrom, remain attached thereto, and must one day return thither to be united with our ancestors. This link is the basis of the ownership of the soil, or better, of sovereignty. It has never been ceded or extinguished, and co-exists with the sovereignty of the Crown

Audience Member 8: How could it be otherwise? That peoples possessed a land for sixty millennia and this sacred link disappears from world history in merely the last two hundred years? With substantive constitutional change and structural reform, we believe this ancient sovereignty can shine through as a fuller expression of Australia’s nationhood. Proportionally, we are the most incarcerated people on the planet. We are not an innately criminal people. Our children are aliened from their families at unprecedented rates.

Audience Member 9: This cannot be because we have no love for them. And our youth languish in detention in obscene numbers. They should be our hope for the future. These dimensions of our crisis tell plainly the structural nature of our problem. This is the torment of our powerlessness. We seek constitutional reforms to empower our people and take a rightful place in our own country. When we have power over our destiny our children will flourish. They will walk in two worlds and their culture will be a gift to their country.

Audience Member 10: We call for the establishment of a First Nations voice enshrined in the Constitution. Makarrata is the culmination of our agenda: the coming together after a struggle. It captures our aspirations for a fair and truthful relationship with the people of Australia and a better future for our children based on justice and self-determination. We seek a Makarrata Commission to supervise a process of agreement-making between governments and First Nations and truth-telling about our history. In 1967 we were counted. In 2017, we seek to be heard. We leave base camp and start our trek across this vast country. We invite you to walk with us in a movement of the Australian people for a better future.

GK: In closing, could you please thank the panellists. Can I also acknowledge and have you thank the museum staff, the organizers of the event tonight, for allowing this space to be used for this conversation and particularly for this panel. It's greatly appreciated and I'm sure that will hopefully everyone's felt welcome and have enjoyed the event.

SF: Thank you Glen, for being our moderator tonight. Good on you mate.

More Episodes

A compelling discussion shedding light on the distinctive narratives of those openly embracing their HIV-positive status and what this has meant historically and in today's world.

Meet Professor Kliti Grice, the West Australian Scientist of the Year 2022, as she embarks on a quest to decipher the Earth's past mysteries.

Join a panel of featured young LGBTQIA+ writers and storytellers as they delve into the fantastical realms and real-world struggles of the exciting new anthology, An Unexpected Party.

Explore Australia's dinosaur legacy with Dr Stephen Poropat as we better understand the science behind the scenes of Australian palaeontology!

As we inevitably move towards cleaner, more sustainable forms of energy, how will a shift away from traditional mining practices transform this economy? A panel of experts explore the implications of this shift with a specific focus on how we see ourselves in a world that increasingly demands environmental responsibility.

Join Megan Krakouer, a prominent Aboriginal leader, as she discusses the nuances of her surprising change of heart on the Voice to Parliament — just a week before the referendum.

Join host Michael Mills in a captivating live recording of the Palaeo Jam podcast during National Science Week!

As AI rapidly evolves, join our panel of experts in an exploration of these complex issues, including how we can harness its power while ensuring responsible and ethical use before we're outrun by its speed.

Do you know how and why your teeth do what they do? Find out all there is to know about teeth sharpening.

Decoding the language of our written and oral histories in Australia.

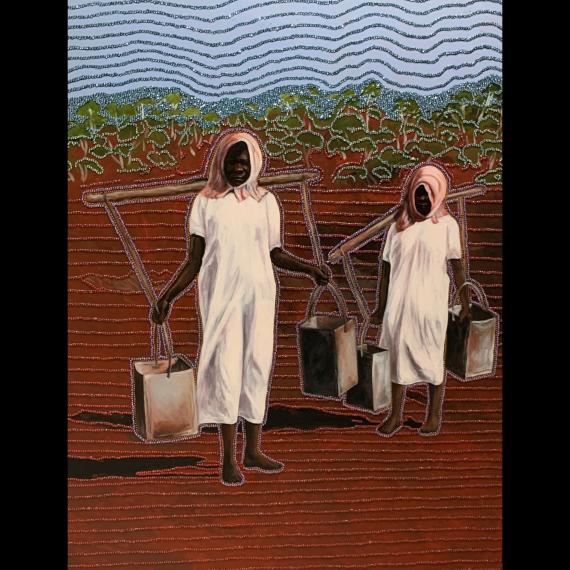

Join us for an insightful talk with the esteemed Professor Henry Skerritt, as he takes us on a journey exploring the captivating art of Jdewat/Ballandong artist Meeyakba Shane Pickett.

No, it’s not a card game but a community initiative helping us further our knowledge of a group of endemic land snails Bothriembryon affectionately called ‘Boths’.

Delve into the way Aboriginal industry professionals are shifting representations, decolonising the media space and creating visibility for Aboriginal people in the industry.

Aristeidis Voulgaris sharesstories from his eclipse chasing travels and discover the complex instruments and tools used in solar astronomy.

Join a panel of experts and community as they investigate the nature of queer bodies, and queer sexuality, in public space.

Join historian Toner Stevenson and astronomer Melissa Hulbert, as they share their tips on how to salute the sun during this eclipse!

Simon Miraudo and Tristan Fidler from RTRFM’s ‘Movie Squad’ are joined by Chelsey O'Brien, Curator at ACMI, as they review and discuss Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland as a foundation for contemporary storytelling in film.

In this one-off Perth Design Week talk, the Museum celebrates the remarkable women in architecture and film in a panel discussion, recorded as a part of its recent award-winning film screening.

Join world expert Dr Chris Mah from the Smithsonian Institution as he recounts his encounters with some of the most unusual creatures on the planet.