Thegosis

The science of teeth sharpening

Do you know how and why your teeth do what they do? Find out all there is to know about teeth sharpening. Join Professor Mike Archer from the School of Biological, Earth & Environmental Sciences at the University of New South Wales as he explains all there is to know about the process thegosis. Learn how and why most animals from sea urchins to guinea pigs, including humans, use and maintain their teeth through the process called thegosis. This enables their teeth to serve as lethal weapons as well as sharp food processors. Find out more about the relationships between teeth, human aggression, beards, smiles, dog growls and many other complex but fascinating animal behaviours that are too often seriously misunderstood. Understanding these might even help to reduce the likelihood of major world wide conflicts such as wars. Looking for more interesting Paleo talks in July then visit the Palaeo Down Under 3 website for more details.

-

Episode transcript

Speaker: Professor Mike Archer – School of Biological, Earth & Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales

Host: Arlene Moncrieff – Learning and Engagement Officer WA Museum Boola Bardip

AM: Welcome to Meet the Museum, our monthly event that takes a behind-the-scenes look at what we do at the museum - not only here, but obviously in other museums and places around Western Australia in particular. Tonight we've got a very special guest to come and speak to us, who used to work at the museum at one point I found out this evening!

For those who I haven't introduced myself to, my name's Arlene. I'm a Learning and Engagement Officer here at the museum, and my colleague Sarah over here, likewise. It's a pleasure to be here and work with you this evening. There's a few bits of housekeeping, if you wouldn't mind me just going through that, which we need to make sure. The first thing is an acknowledgment of country, so I'd like to pay my respects to the Whadjuk Noongar on whose land we meet and learn today, and pay my respects to the elders, past and present. I also pay respects to any other First Nations people that might be joining us this evening, too. Welcome.

For Meet the Museum tonight, or this month, I’m delighted to be welcoming Professor Mike Archer. I've got a bit of a bio that I'd like to read out and he's been quite happy for me to do that because it shows you where Mike's been for a good space of time. Mike was born in Sydney but grew up in the USA and after graduating from Princeton University, he returned to Australia. He did his Ph.D. at the University of Western Australia, became curator of mammals at the Queensland Museum, a Lecturer at the University of New South Wales, Director of the Australian Museum in Sydney, Dean of Science at the University of New South Wales and now Professor and Member of the Pangaea Research Center at UNSW. Round of applause for that, I think!

I'm almost done, Mike! His research focuses on the deep past; such as the world heritage fossil deposits at Riversleigh, the fragile present; such as conservation through sustainable use of native resources, including keeping native animal pets, and, securing the future based on the wisdom of the fossil record and trying to bring extinct species - e.g. the gastric brooding frog and the thylacine back into the world. So, without any further ado, I’ll hand over to Mike and I look forward to this wonderful presentation on Thegosis. Am I pronouncing it properly?

MA: You are Arlene. Thank you, Arlene, and thank you to Kenny for helping to organize this talk. I should preface this by saying now for something utterly and completely different for any of you who have been at the conference. That's not my dentition, despite what it might imply there, but it would explain some of my bizarre interest in teeth.

I'm a palaeontologist, primarily, but interested in Mammalogy. I love to watch living animals do their thing, and every now and then these two zones interact. Is there anybody in the audience who's a dentist? I'm safe! Otherwise I've got a suit of armor over there (laughs). I have a problem with a lot of dentists. Not all of them. Many of them are smart, but everybody's got a problem with dentists at some time or another. They're good at administering pain beautifully, but it's not those issues I have. It's whether they really, frankly, understand the way teeth work. Some of them do, a few of them do, my own dentist in Sydney does, and we have collectively been trying to work with other dentists to figure it out. I've even given lectures in the University of Sydney's Postgraduate School for dentists. One of the professors there heard me have concerns about what Dentist seemed to understand about how teeth work, and he got me to give a series of seminars to them. They were sequenced over a few years, and the first time I gave a talk, which is what I'm about to give to you, I was introduced as “Mike Archer is going to talk to you about abnormal dental activity”. No! It wasn't abnormal, what I'm trying to say is it is normal. Slowly I got him over the hump and by about the fourth year, he finally said, “now Mike Archer is going to give you a seminar about paranormal dental activity” (laughs). Progress, you know!

I know there's a coterie of dentists out there who’ve heard these arguments, but basically what has to happen is, while we make the logic of the case here, we have to get into experimental stuff to start to demonstrate the reality of thegosis, and it is something that has to be taken seriously. Not just by us and by palaeontologists, but by dentists. That's my main point. You have some issues that you have to deal with occasionally, and you have dentists you have to deal with occasionally. It's really prudent to try and pick the dentists carefully.

If you want to try all this out, it might not be good for you but, next time you're sitting in a dentist's chair just say, “What do you know about the thegosis?”. If you feel their hands freeze, you know, while they're attending to you, you may drop the topic straight away. But if they happen to know about it, we're probably sitting in a good chair!

All of us in this room know this, Charles Darwin deduced it a long time ago, but there's no question about it; Human beings evolved from other great apes. If you were ever in any doubt about that, Tadah (gestures to self) I'm absolute proof! Because dentists started their profession before Charles Darwin started his big deal, a lot of them don't feel the need to understand the evolutionary history of humans before they sit you in their chairs. They have some preconceptions about how humans use their teeth or how any animal uses their teeth, that I want to address first. These preconceptions need to be rethought. The first one, and it seems kind of intuitively sensible, is the idea that the way your teeth are, just before they erupt, is the perfect tooth. If we’re thinking about a couple of hundred years ago, the belief was God made those teeth that way, so they must be the perfect form of the tooth. Any alteration of that form was a degrading of the tooth form. That’s a kind of subliminal preconception that they have to work with, and it's actually not true.

Here's an example: These are three lower molars of the human jaw, that's the wisdom tooth. I'm just curious because I asked my students this, but how many people here have a wisdom tooth? How many people don't have one? How many people know that they do not have one at all - not that it's been removed? You're the advance guard of humanity, because that's what's happening. Our jaw, our face has been shortening, neoteny and so on, so there is less room to get that third molar up. There are people now who are not developing it at all. It's uncommon, but it happens.

Anyway, there's that third molar, the wisdom tooth, and I draw your attention to the back of it here. You can see that it's lovely and bumpy and rolling. Well, that's the way it looks like when it erupts in your mouth. Look at the teeth in front of it, that have been doing work before this tooth finally finished erupting. Already they're showing dental wear, but look what's happening. These bumps couldn't cut food, they couldn't even cut butter. They’re just rounded stumpy bits on the teeth. It's only when those kind of rolypoly things like that are starting to wear and the enamel wears off and it exposes the softer dentin in the tooth, then that scours out and it creates all kinds of blades in the enamel where there weren't blades before. The irony of this whole thing is, the more worn the tooth is, the more functional it is. It's not the unworn condition we should be striving for. We need these teeth to wear in order to work properly.

We are what are call ‘horizontal segmented biters’. When we process food, we're moving our lower jaw across our upper teeth. If there's food trapped there, any of those horizontal blades, everything in the lower tooth is matched by a blade on the upper tooth, sweeps across each other and snips food into tiny little bits. It works beautifully. The second thing that they're absolutely convinced of is that all wear features on your teeth result from chewing food. I know a lot of my colleagues still think that's the case, that somehow the only thing causing wear on your teeth is the food that you're chewing. Again, it's not true. A lot of the wear that's on our teeth occurs when there is no food there. This is where the thegosis comes in - its tooth-tooth wearing. It creates a very special kind of wear across the teeth. That's extremely important for us.

The third thing that they're convinced of, and we have a lot of paleontological colleagues who are convinced of this as well, is that the key features you need to pay attention to in understanding how teeth work, is the cusps of the teeth. In reality, that's not true, again. Cusps are important and they’re useful for working out maps and looking at comparing cusp patterns in different animals. But the functional part of the tooth is not the cusps, it's the blades. These are the cusps of a tooth. This is a portion of a tooth of an insectivorous marsupial. You can see these cusps. They are important because they puncture into the food that you're trying to eat. But it's the blades that follow right behind them that’re the most important thing, they're the things that cut the food into smaller bits.

We have lots of paleontologists who study aspects of this. This area here was originally worked out by Crompton and Hemi as being a tremendously important thing to compare animals about. They were looking at the ‘shadow zone’ of what's important. It's the blade, the cutting blades, and if you study the blades, you'll understand how these animals cut. These guys, that particular one, is cutting vertically. We cut horizontally, but blades are the key features that make this workable.

The fourth preconception is that molars engage in mortar pestle grinding. It's as if when they’re talking about tooth grinding to a dentist, it's as if they're expecting you to put your food in a mortar and then grinding it around. They think that's what your teeth are doing, grinding the food. That's not what's happening again. What's happening is the blades - in the case of carnivorous or insectivorous animals, they're doing these blade cuttings vertically. As the teeth close on each other they slice the food between these blades. On the upper tooth there, there's an opposite V-shape that's matching the one that traps food and snips it into bits. Even in humans, when you get an old human like that, a geriatric lad, he's still perfectly capable of cutting a piece of steak up because he has horizontal blades as he moves his upper teeth across his lower teeth. Those hard enamel edges, all that's left now, of those teeth, still meet each other upper and lower and cut the food into bits. Blades are the things that are the important feature of how this works.

The fifth preconception has to do with the muscles. When you put your fingers on the side of your head here and you clench the teeth, you'll feel a muscle bulge out there. That's the temporalis muscle. If you clench your jaw here, that's the masseteric muscle. Those are two standard masticatory muscles. They're really important and they're the things that create the force enclosing your lower jaw on the skull. All mammals tend to have this kind of feature. There's a third set of muscles they regard as masticatory muscles and these are things called the pterygoid muscles, and they actually attach to the inside of your lower jaw and move over to your skull. These are muscles that are traveling in a very different direction from the temporalis and the masseters. That's the point. All three of these classes of muscles are not just muscles of mastication or eating. That series of muscles here, particularly this muscle called the lateral pterygoid, is attaching to the inside of your lower jaw and then moves over into the skull. The fibres are moving transversely or obliquely, they're not even moving the jaw in the same way that these muscles are doing. It's a different kind of a muscle. The temporalis and the masseteric muscles have a sharp snapping motion. They act really quickly. They're fast acting muscle. The pterygoids are slow acting, powerful contracting muscle - different.

What are they doing? They're primarily moving the jaw sideways. Now, for a lot of herbivores, that's important too, they are using that to move the jaw sideways. For people like us, animals like us, that's moving our jaw sideways at a time when thegosis is also occurring. It's the muscle that drives teeth against teeth. More about that in a minute. So we have five anachronistic ideas here, what do we do with them? No problem, trash them! But for dentists to do that is almost impossible because they're really foundational concepts that a lot of dentistry is based on. I know because I've seen what they're teaching.

There is a sixth one, and the sixth one is the one I really want to focus on. The idea of tooth grinding. The dentists regard that behaviour to be abnormal. They think it's dysfunctional, and if there's any way of dealing with it, they think it should be stopped. Here we have a major disconnect between what I'm trying to suggest, and what they presume. There was a time when we did understand a lot about this and it was common knowledge. Homer, 1850 B.C in the Iliad, described what happens when hunters were out hunting boars. You know, big, ferocious pigs. They're quite lethal. They knew when they had dogs and horses and they were chasing these pigs, the pigs would seek cover in the crops of vegetation and then they would listen. They would wait and then they would hear what sounded like “whack whack whack whack”. At that point, what they knew was happening is the boar was sharpening its teeth. It was ramming its lower jaw hard against its upper jaw, and razor sharpening its teeth getting ready for battle. The moment they heard that sound, the wisdom was to brace your spear in the ground, because that boar was going to charge out. They knew all about it, it was quite common knowledge.

There are some old paintings which are wonderful that actually demonstrate where painters are showing battles. If you look carefully at a lot of these older paintings, you'll find people who are savaging other people with their teeth, knowing full well that they have their teeth as weapons. Just like that pig knew. My point, and this is what dentists don’t think, that magically teeth sharpen themselves, get themselves ready for function. That when we eat, somehow that sharpens our teeth and it's simply not true. As we know, use dulls tools. All those tools on the left have to be sharpened. Once they're used, they start to dull. Teeth are tools. So again, if you're going to use them, it's going to dull them. Use won’t sharpen them. You have to have another mechanism to actually sharpen those teeth.

This is where Ron Every, who I'll introduce to you in a second, came up with this term. Thegosis is a Greek meaning for sharpen’. As he said, it's sharpening a tooth, beak, or bill by deliberately and forcefully grinding it across the surface of an opposing tooth, beak or bill. If an animal has two hard parts, upper and lower, whatever the animal is, it can use those two sections to actually sharpen as well as to eat.

If you've ever had a parrot sitting on your shoulder, you may have heard this sound (sound of parrot sharpening its beak played). That's a parrot sharpening its beak. Why does that bother you when you hear that sound? It just makes us shiver, doesn't it? And why? Because instinctually, like those hunters that Homer talked about, some animal is sharpening its teeth, getting ready for battle. It's an instinct, we can't avoid it. As soon as you hear that horrible sound, you know what's about to happen. If you're sleeping in bed and your partner's starting to do that, you know, there's an animal under the bed! It's going to savage your foot when you put your foot out on the bed. I don't have any recordings of turtles doing the same thing, but they will be doing that as well, using their beak in another way, to sharpen the beak, to restore the cutting edge of their beak.

This is the guy who came up with this concept. A wonderful man, Ron Every. He was a New Zealand dentist who was very smart. Unfortunately, he's gone, but I met him when I was in Perth years ago. He was trying to explain to one of your former directors, David Ride, who was a paleontologist, that he didn't understand how teeth work. David didn't take well to that. I remember this meeting being somewhat stressful, but I was listening to what he was saying and what he was saying made so much sense to me. I spent more time with him. I went over to New Zealand. We had lots of interactions, and he's the guy who actually began this whole game. If you're going to sharpen your teeth, if you have opposing hard parts, whatever your animal is, you can use those to do that.

That's not the only way you can get sharp teeth. The losers are the other ones, like sharks and crocodiles. As paleontologists, when we go to a fossil deposit that’s producing a shark tooth, you'll probably find thousands of shark's teeth. There are many more shark's teeth than there are sharks, because they're constantly shedding their teeth. That's how they maintain tooth sharpness. As one tooth wears and breaks off, another one rolls up and replaces it. Crocodiles do the same thing, only the teeth erupt from directly under the preexisting teeth. If you can thegos, you do. If you can't, you lose. Two simple systems. The problem with the losers, is that the teeth for most of these groups alternate, so they don't tend to contact each other.

I know, Steve, there is a couple of groups of crocodiles who have misbehaved! We have heterodon crocs. Some of them do probably have teeth that contact, and it would be really interesting to look and see what they're doing with their teeth. For every generality I'll come up with, there'll be exceptions. Sorry . Yes, that's another one.

Audience Member: Unintelligible comment

MA: That's another easy way of doing it. If the teeth don't actually touch each other, one way or another they can't be used to sharpen the other teeth. Here's how a thegoser does it; what you're looking at here is a boar, a big boar's skull. We're looking at the boars upper canines and the Boar's lower jaw with its big, lower canines. This is why they were so feared by people who used to hunt these things. Those lower canines are lethal. I mean, the second or third most common thing that kills people in Africa is hippopotamuses, right? They have the same kind of teeth. When they put those lower canines up into you, you're gone. These teeth are not born that way, they manufacture those teeth. They manufacture them into weapons through thegosis.

This is what's called the centric position, where the lower jaw is smack in the middle, and it's held tied up against the skull. You'll see here, this is what's left of the upper canine. It's their stumps. In the second stage here, the boar, while the teeth are clenched together like that, pulls the lower jaw down. This is what happens. This upper canine tooth here sweeps up the back of this tooth, just like you'd use a stone to sharpen a knife. It works beautifully. As the enamel is stripped of the edge and dentin is stripped off, it leaves you with a razor sharp leading edge. They have sacrificed all the function of their upper canines to make them into sharpening tools. It's one of the classic examples of how this works. In a sense, they're sharpening it by pulling the jaw down. If they were going to use the jaw to eat or kill, they move the jaw up. They're sharpening in the opposite direction. It's the same kind of thing we do when we go to sharpen tools. If you ever used a stone to sharpen a knife, you know to pull the knife backwards, you don't push the knife against the stone . That's what these animals are doing as well.

Baboons have the most extraordinary weapon system that manufacture the same way. Upper canines, lower canines, and then the anterior premolar, the bicuspid. In your own mouth, you've got two bicuspids in each quadrant of your jaw. They are two teeth right in front of the molars, and they look like normal teeth in most people, but on the other hand, look at one of those teeth here in a baboon. You note that the anterior part of it, the front part here, it's got enamel going all the way down a long area. When you close this jaw on that tooth, that tooth becomes like the pig's upper canine. It's a sharpening tool. As the baboon opens its jaw again, that tooth strips up the back of this and it turned. The back surface is razor sharp, and all of that has been stripped away in the process of leading to that sharpened edge. They're not born that way. These are animals using thegosis tooth grinding to deliberately sharpen their teeth and turn them into ferocious weapons.

In this case, here's a cat. You're looking at the upper fourth molar here. Notice the difference in the texture across this tooth here. It's kind of bumpy and lumpy and it's rather uninteresting. Then you see these shiny areas right here, with blades right up to the top. What's happening here is when the cat closes its jaw, this first molar in the lower jaw comes inside the upper pre molar. As the jaw opens up, it strips this tooth up this way, constantly removing dental material and increasingly maintaining the sharp bladed edge. It's a simple system. Here's another animal showing the same kind of things. Larissa has probably seen 100 million of these kind of photos.

Here is a taper. We've been trying to explore this a little further, haven’t we? You can see the tapered molar. There are two very different kinds of structures here. These are worn areas. There are thegosed areas where enamel has been removed. There's even dentin being exposed. These have a razor sharp leading edge, but again, manufactured by stripping the enamel up this way, pulling it away, sliding off the top and leaving a razor sharp edge here. Here's what the thegotic facet looks like. All fine linear lines. And here's where food is actually resulting in a lot of different wear and that's what you will see in other parts of its tooth, but these are where thegotic areas are and wherever there's been this kind of activity, even on those blades, it's restored constantly by thegotic activity. Keeping the blades sharp. It’s what you would expect when you look at a knife. You're sharpening it, and you're pulling material away from this area and sliding off that edge, leaving you with that sharp leading edge. That’s the way these teeth are sharpening themselves.

I saw this in an airport I was in not long ago. It's fascinating to me. if you've seen these metal luggage racks, look at it carefully, it's just like the same process going on here. As these plates come around the corner, the metal slides across metal, and you get beautiful, thegotic type stripes. Tooth tooth, this is metal metal. In these areas which have very dull shine, that's where suitcases are wearing the thing and they're not getting metal metal re sharpening. It's an analogous situation to what teeth are doing.

Back to human teeth again, if you actually look in detail at your own teeth, if you ever get a chance or get a little hand lens, have a look at your teeth. If you ask dentists have they ever seen shiny little flashes back on teeth, they don't see the importance of that. Those are thegotic facets. They've been very carefully honed to produce sharp leading edges. That's an area where food is causing blunt wear on the cusp. It's not a thegosed area.

Let’s dip into some of the marsupials that are famous in Australia. The most specialized carnivorous mammal that evolved anywhere in the world is the marsupial lion. It's an amazing animal. The biggest ones might be 160 kilos in size. Why are they so specialized? This is a lower jaw and that's all the dentition consists of - A gigantic bolt cutting pre molar with a razor sharp blade edge. The only molar it's got left here in the lower jaw has a blade that joins this blade to produce a powerful cutting mechanism. How do they maintain that? In part, if you look at the upper dentition here, you can actually see all that's left of the whole molar row of this animal, is a tiny stumpy thing that is absolutely incapable of being in there to eat or process food. It's not even sloped at an angle where it would hit food. It’s sole function is to help sharpen this blade, as it strips up that area where the lower blade doing the same thing. Again, an incredible sharpening mechanism.

Wombats may be one of the most amazing ways an animal has used thegosis to change its fortunes in life. Wombats are most closely related to koalas out of the living marsupials. Koalas have what are called selenodon molars. If any paleontologist looks at the molar they immediately know it’s a leaf-eater. They have a very distinctive W shape on the upper and the lower molars. Wombat babies, when you have a look at their teeth before they're actually out eating grass, have a very similar little tooth. It's not quite as spectacular as a koala’s, but it has the same selenodon patterns. Before these little buggers actually get out of the pouch, and this must hurt Mom, because they're sitting on the mother's nipple. They're grinding their teeth and so by the time they actually leave the pouch, for the first time when they can eat grass, they have ground away the whole of their inherited molar crown. It's gone. All they’ve got now are teeth that look like this. Using their thegotic transverse motion, it's a little hard to see here, but the dentin has been carved into transverse ridges. These teeth are perfectly suitable to eat grass. A koala could not survive on grass. It would starve to death, selenodon teeth are not going to process them - not koalas anyway. In the same way if you put a wombat up a tree, it's not going to do real well either. On the other hand, there's some interesting ecological discoveries being made which haven't been reported yet. Somebody has actually found a koala with a tail, which is spooky at any rate.

Let’s get out of mammals for a minute, sea urchins. Kevin Scully, another dentist in New Zealand, was curious about this. If you've ever turned a sea urchin over and had a good look at the underneath, they have what's called, famously, the Aristotle's Lantern. It's a series of teeth that oppose each other. They go around chewing seaweed off rocks, very coarse, very abrasive kind of an activity. Yet, when you look at them, you see these beautifully sharp teeth. Kevin probably didn't get ethics permit to do this, and I don't know if they need to do that for a sea urchin, but out of curiosity, he actually picked one up and snipped the end off one of those teeth. He was curious to know what they would do now that they've got a tooth that doesn't work like the other teeth. He came back in two weeks to that marked sea urchin, he turned it up and there was that broken tooth. It now had sharp bevels and new blades on it. It was busy using the other teeth to restore the broken one and recreate a functional tooth.

We all tend to pay lots of attention to the posterior part of lobsters, which are pretty yummy. But the next time you hoe into one of these little dudes, have a good look at the mouth and have a look at the teeth that are in them. This is chitin, we're not talking about enamel here now. Here's a lobster's lower jaw. If you look at it close up, you'll find the thegotic - the fine striations, the stripped of chitin, leaving a sharp cutting edge. They're constantly restoring this to maintain the function of the cutting blades.

It started everyone thinking, is it possible if we're talking about a thegotic activity here, that’s not only in humans and pigs and primates and wombats and everything else, but down into sea urchins and invertebrates, is there maybe a thegotic centre in the brain? Is this an instinct that's basically ancestral for all animals and we just haven't realized it's been overlooked? Is there a part of the brain that's actually dedicated to being able to re sharpen our own teeth? I don't know.

What about humans? With your tongue, just feel your lower incisors right at the front and just feel the insides of the edge and then the outside. I would venture to suggest that the insides will be sharper than the outside. Is that true? It is certainly for me, and most people. How about your uppers? Use your tongue to feel the inside of your upper incisors and then the outside, which is sharpest? Outside. It's the opposite. That's not the way they're born. They're born with complete enamel over it. You've manufactured them. You've actually used your teeth in a way that does that. Here is a lower incisor, sharp inside edge and rounded outside edge.

This is what your teeth look like soon after. That's a four year old's lower incisors. There's no blades there at all, just little stumpy humps. And here's a six year old, he's already started to thegose off those tips of the cusps and then you're into this situation by the time you're in your teens or your twenties. We're manufacturing these throughout life. It's not something that's inherited. The idea that somehow that's the perfect lower incisor form is ridiculous. It couldn't work to cut foods. Here’s the upper incisor, more rounded inside and sharp on the outside. This is what happens when you go to eat. Just metaphorically, think about eating an apple. You end up moving your lower jaw out and you bite down on the object you close and then you pull the lower jaw back. That's the normal way we cut things. If you were cutting a piece of meat, you'd put the meat in your mouth. You move your lower jaw out a bit and come sliding in across the upper teeth. So we're using horizontal blades again to cut the food that way. This is the standard. That's why we would say we have a horizontal segmented bite. The chimpanzee is demonstrating the same thing. It's like holding a pair of scissors horizontally. Again, that's that situation that we were talking about - that the older you get, frankly, the more functional your teeth become because of this kind of dental activity.

How do we do it? This is an interesting picture here. This is one of Every’s patients, and the teeth are now in centric position. They’re closing the teeth right on top of each other in the middle, keeping the jaw in the middle. What you can see here is the upper right first incisor and the lower right first incisor. Note the upper right first incisor has a notch on it. And then you go around the dentition and says clearly that lower first incisor is not doing that. As he moves the jaw sideways, what he finds is that the tooth that is doing it is the right canine. You have to move the jaw away, off to the side, pulling it this way to be able to get those two teeth to meet in that kind of a posture.

When you look at somebody with a face like that, it's kind of snarly, unpleasant look. We'll come back to that in a minute. You have to have these extreme dental movements. This is one of the other problems that dentists have. They give you a dental filling, and you go home at night and you can feel something's there, that he's done some kind of work there. When you're asleep, you're starting to grind your teeth and your teeth will slide across that constant. You're instinctually trying to restore the blade edges, the natural blade matches. You've got upper and lower. It hits this bump that that clumsy dentist left there and you'll tear it out. Then you'll go back to the dentist the next day and he'll abuse you for having ruined his work and charge you again for having put in another.

If they would really understand this blade to blade issue and how these have to work, you've got to take a lot of time to do dental restorations to make sure they are perfectly matching. Part of the problem there is, they used to use what they called dental articulators. They would take a cast of your teeth, lower and upper, if they were really going to get serious about it. Then they put them in a device, the dental articulator, that's supposed to simulate how you move your jaws. After you've had dental work, the dentist usually says to you, “just gently grind your teeth” and you put a little piece of paper in your teeth to see what's touching.That's not what you're going to do when you go to sleep at night, he's not going to ask you to try that out! There's a high probability that you're going to have an impacting series of teeth because he hasn't realized how much movement you're going to naturally undertake doing this kind of a thing.

When is it done? We don't tend to do it during the day because it's not considered too sociable to be grinding your teeth. But as soon as you go to sleep, it's all over. You know, you've had a bad day, somebody’s abused you, you lost your job, or somebody told you to do what they shouldn't have told you to do. You have a dream and you transmogrified that tension, that stress into a kind of a metaphoric battle. Whatever you're doing in your dreams, you will start grinding your teeth.

This is a wonderful description here. “Snuggled in bed, i'm asleep next to my husband and in the middle of the night i'm jolted awake by a sound so annoying it's difficult to describe. It's like awful high pitched whine of metal grinding on metal, like fingernails scraping down the chalkboard”. Some of you are old enough to remember teachers who use chalk on boards and well, it's horrible. “It's my husband in the bed!”. Here’s that sound. It's another human doing it. It's a horrible sound. Now you know why, because basically your brain is telling you something is about to attack you.

Sometimes people get so stressed, they don't wait for the evening to do it. Our dear King here has started doing it automatically. John McCain is a master at doing this during the day. He was doing this so often because he was under so much tension. He just couldn't wait for nightfall to threaten people. Sometimes when people do this, if they are really under stress, it can cause a lot of pain. I don't know if anybody here has had that problem. It's what's called myofascial pain syndrome. What's actually happening there is curious. The dentists, I think many of them do not even understand what's happening. They think it's because you're grinding your teeth. It's not so much because you're grinding your teeth, it's because you're going extreme grinding. You're so tense, that if youreally self examine yourself during those times when it's happened, you'll probably find you've been under special stresses that are causing this. You actually, can literally dislocate your jaw. It'll snap back again, but that will cause and leave you with pain on the side of your face. It's an unpleasant thing, but it comes from extreme stress. It's nothing to do actually, with the way your teeth work.

This is what dentists call bruxism. They regard it all to be abnormal and it should be stopped. Yet that's ridiculous. You have to have tooth grinding to get those sharpened teeth and to maintain their functionality, but you can do too much of it. It's not their job to fix it, that's my issue with a lot of these dentists. At that point, they should refer somebody who's having a lot of problems with this to a psychologist to find ways to lower the stress levels in their life. There is nothing that they're going to do that will fix the problem. They're just going to delay it. They're going to give you a splint or something, and it's going to cost you thousands of dollars and you're just going to grind the hell out of that splint. It's not going to do any good. It's just a very expensive aspirin. There was an ad I saw recently about this and it says, ‘how can I stop grinding my teeth using splints?’. That will not stop you grinding your teeth. If you don't understand why people are doing it, you're in the wrong game.

There's a lot more to this than just sharpening the teeth in a natural kind of way. Teeth are also used as weapons, and we do need to understand that. It turns out that the second most common thing that bites humans after dogs, is humans. We are notorious biters. Any careless dentist who's ever had his hand in an aggressive kid's mouth, and the kid didn't want those hands there was taking his life and his fingers in jeopardy! Why do we call them ankle biters? Because they know that's their instinctual weapon system. They've got very effective, sharp teeth that are quite capable of cutting. Yet we socially beat these things out of them.

There's two of those little paintings I was thinking about, Massacre of the Innocents, Ruben 1638. This guy is attacking these people, and this woman is just unhesitatingly instinctually savaging his arm with her teeth. This famous painting, Dante and Virgil, 1850. They're going for their throat and tearing it out as Dante and the devil are watching this. There's no question about it. We do know that we are biters. You think about this famous episode, when Mike Tyson bit his opponent's ear off! He said it was an accident. No, it wasn't an accident. If you actually examine the film carefully enough, you'll see him spitting out his mouth guard. He knew fully well what he was doing. He was going to take that guy's ear off and he did it. It happens a lot.

In 1837, a British man sued a woman who bit off half his nose after he tried to kiss her without consent. The judge ruled against him, stating that when man kisses a woman against her will, she is fully entitled to bite his nose off if she so pleases. It's a nice legal judgment reflecting the same importance of this thing. Biting is what people do. You just have to sort of lower the inhibitions. That was a thumb. Some nice little football game here, that's the most extreme one I've seen. When the scrum was broken up, there was a hand on the ground and somebody sawed right through an opponent's hand. There's nothing defenseless about our teeth. We have lethal ones. The movie 300, that's what they should have said. Not “we are Spartans!”, we are biters!

Why do men have beards? Sometimes there's ambiguous reasons, I suppose, but biologically they're really important. When a male goes to attack another one, they go for the throat. This is the ridiculous narrow bit of our body where all our central services come up. In order that we can turn our head around when we come out of water, the first amphibians had to check who was behind them, so we've got necks. Which is a curse. That means that's where the lion jumps for, not your foot, it goes for your neck. Humans do the same thing. If one human attacks another human, they'll go for the neck. The beard is a false throat. The person who's attacking will close their eyes because they don't want their eyes damaged. The tactile sensation sits in their mouth, and the first thing they feel will be the beard and they'll clamp on the beard. That's why we've got the beards. If men have shaved their beards, they're kind of implying that they're not expecting to be savaged or are get in bloodthirsty battles. There's no doubt about it. Beards are a very functional thing. You look at lions. Why do male lions have big beards like that? Again, they're protecting their throat.

I found these images. This is in 2021, when Afghanistan was being abandoned by the allies and so on, and Taliban fighters, all normal standard beards. Yet when I scanned this whole plane full of people that were trying to get out of Afghanistan, I couldn't find a single full beard. It's kind of interesting that maybe the less aggressive people, were the ones who were the keenest to get aboard the boat. There was only one I could find that has a beard and he seems to be fighting.

So, Jacko from the AFL. This advertisement used to be out there to sell Energizer batteries. What were they thinking? They just said to him, you know, because he was a popular character, “get up there in front of the cameras and convince them to buy batteries”. Well, what he launched into subconsciously here was the full on aggressive demonstration of a male who's about to attack you. He's got all the symptoms going. His clenched eye, because that's he's doesn't want to get hurt with his eyes. He rushes in there. He's got the lower jaw out here in the thegotic posture of sharpening his teeth. He's even raising his lip here to instinctually show you that he's sharpening his teeth. It's a very distinctive set of features. The only thing he's missing here, we can't hear it, he should have been growling at the same time. I actually went to the company that makes Energizer and ask, could we use this in a publication? And they said, absolutely not. They don't want that image out there anymore. So I think they finally realized maybe this wasn't the best way to convince people to buy batteries.

Understanding these facial signals that are associated with tooth grinding and preparation for battle are really important. Just listen, it's a dog growling. It gets worse. What would you do, facing a dog that was making those sounds? You instinctually would know to back away slowly.That growling sound is mimicking tooth grinding. That's what it's doing. We know what the bark, it's a frightening punchy sound, but the growl is totally different. Even humans, if you get a human really angry enough, they will do the same thing. They will growl, simulating the tooth grinding if they're not already tooth grinding. It's really, really a good idea for kids to learn these signals.

Here’s the opposite. It's all related here. When you look at that girl's face, you actually have no idea what she's thinking. You've come into a room, that girl is there and you don't know whether she's mad at you or whether she's okay to see you. You don't have any clue, until she smiles and suddenly you've got a completely different feeling about that person. It's the same face, the only difference is a smile. What's she doing with the smile? She's exposing her teeth in the centric locked position, demonstrating that she's not thegosing. The smile is an appeasement gesture just to say “it's safe. You can come in now. I'm not sharpening my teeth. I'm okay”. It's a very important social gesture in mammals. We all do it. The primates do these sort of things. Every time, it's not an aggressive thing, it's an appeasement thing to tell you that their teeth are quiet and it's okay and safe to come in.

Coming to the end of this, this is one of the problems. Thinking about how you might try to avoid World War Three if we really understood the relationship between tooth grinding, fighting, facial signals, it could make a difference. Nobody in their right mind would be able to go up to any one of those animals and give them a smack. You can't, because they're all displaying. Like the girl whose displaying the smile, it immediately stops any feelings of aggression you might have. But in this particular case, you could not go ahead and aggress that person. That's really important. We have those instinctual inbuilt indications that control our behaviours. But, modern warfare doesn't do that. Unfortunately, all the killing that's going on in modern warfare is in distance. Nobody sees the faces. There's no chance for appeasement gestures of any kind to lower the level of tension and aggression on the part of the person who's doing it. And so bang! I don't know what the solution to this is, but somehow conducting war like that doesn't work anymore. I mean, in the old days with gladiators, the gladiator could say “yield!”, any number of things that could stop the aggression and stop the killing. We can't do that anymore. Unless maybe, I don't know, try this one... thunder grind! We put all the aggressive people in a big theatre like this and have them sort of snarl at each other and maybe get it out of their system that way. At least they'd be seeing faces and they'd be able to respond to the aggression from other individuals.

Guinea pigs. Everyone thinks about guinea pigs as being so sweet, they wouldn't hurt a fly. If you ask anybody who's got a pet guinea pig, ask if you could just come in for a while and interact with their guinea pigs. Just poke it gently. Poke, poke, but don't hurt it. Just poke and the guinea pig will move off. Then go over and follow it, poke, and the guinea pig will move off again. You might get three or four of these goes, then all of a sudden you hear the guinea pig sharpening its teeth. If you could speak guinea pig-ese, it would say, “if you do that again, I'm going to bite your finger off!”. Guinea pigs are very potentially aggressive animals.

Just listen to some of these sounds. In this particular situation, there's a male guinea pig. He's got a harem, and he's very intent on keeping that harem. He was aggressed and he was a little annoyed. Here's his sound. He's sharpening his teeth. You can hear vocal in there as well, but you can hear the teeth rapping. He's using the lower teeth, lower incisors to sharpen the upward sizes, getting ready for battle. Then this perverse experimenter introduced another male guinea pig into his area, and that didn't amuse him at all. Off he went again!

Sheep, I love them. I love this image, of that wonderful, bizarre movie, Black Sheep, the New Zealand one. Absolutely brilliant. But the sheep is quite capable of grinding teeth and it has to do it again. Not so much because they're going to savage or fight, but because they've got to sharpen their teeth and make sure they're adequate to cut plant food. That's pretty much the game.

So thank you. I’m happy to answer any questions (applause)

Audience Member: Thank you so much for this talk. It's been really eye opening because I've never thought of it like this before. With the talk about smiling, I heard some time ago that chimpanzees actually don't smile how we do. Smiling by showing the top teeth is also a sign of aggression for them. Why do you think that's different?

MA: I'm not sure, but most primatologists say the smiles in primates are appeasement gestures. I've heard something about that too. It might be that it's kind of like an early warning, a quick flick of the teeth to show you There's these nice, functional, big canines. I could imagine that's possible, but in most cases, the primate smile seems to be an appeasement gesture. They haven't got the same capacity of dental movement and facial movement that we do because they have what's called a canine locked occlusion. The canine is sufficiently long that they don't have much lateral movement of the jaw. So slightly different, but broadly, all of them seem to be displaying the same kind of feature.

Audience Member: Hi Mike, what happens if you've gone down and you've got that nerve. Wouldn't that be a natural stop. Like you've gone and got rid of the dentin, can you go down too far?

MA: No, it's interesting, It doesn't appear to be the case. The nerve in those situations, the nerve retreats in advance of that kind of tooth wear. It's not like it's fixed in the extent to which it goes up into the crown. I've asked dentists about that, but they say no. When the teeth are worn naturally through thegosis, they think just from eating, the nerve endings start to degenerate, and they're pulled back. They're always below that surface. But I have seen, in one of the weird kinds of pre carnivores, one that had done this all through its life, it wasn't going to stop then. Its crowns were completely gone and it was thegosing its roots. The roots were sticking up and it was keeping the edges of the roots sharp to be able to continue to be able to cut food.So it can be extreme behaviour when this happens. But yeah, that's a good question.

Audience Member: I had a specific example that kind of leads into a question. Horses and elephant's, the end of their life is marked by the complete wear through of their teeth, and they get to a point when there's nothing left and they basically die of starvation. How does that sort of fit into the thegosis idea?

MA: Interestingly, with elephants, they have a different kind of arrangement, like some kangaroos. The elephant's teeth actually move forward as the teeth are worn out. They get down to a real flat level and they drop out. A London keeper in the zoo actually was the first person to find that out, scrubbing the head of the elephant and a tooth dropped onto his foot.

Horses, because they have very hypsodont teeth, a very tall crown, they're still going to get a long run. But once you've got a tooth that actually has roots on it, then it has a limited amount of tooth material that can be made available. There are animals like wombats and rabbits and a whole lot of other animals that don't form roots. They maintain a permanent capacity to keep producing more crown, even dugongs can do this, so they never run out of teeth. Those pigs that we're looking at do too. That can be a problem. You've got some animals like that the babirusa, where the upper canines actually don't get used in the same way to thegose the lower canines, so they end up curling around. I've seen skulls where they've actually pierced their head! There's not a perfect system going on out there. There's problems sometimes.

Who's a horse person here? How old does a horse normally get? We're only talking about what would happen in captivity, in a captive situation.

Audience Member: An observation from that. During mask wearing, I took the dog to see the vet and we had to meet in the courtyard and the dog hid behind me. The vet said “I'll have to take my mask off”, and took his mask off and smiled and the dog came out. He said that the dog's need to see that.

MA: That’s a smart dog! If that is a normal dog behavior, I'm impressed. They do say dogs read our faces extraordinarily well. We've been with them at least 10,000 years? They've cursed us with having short stubby noses, because supposedly they do all the sniffing for us now. It wouldn't surprise me if a smart dog would pick up on those gestures. Yeah, that's interesting.

Audience Member: Really interesting talk there. I hated every moment of the teeth grinding though, so thank you for that! My zoology teacher once described herbivores as having very well-developed molars and carnivores, not having well-developed molars. How would you fit that into a thegosis? And would you kind of contradict what they're saying?

MA: Yeah, I would. Carnivores and herbivores have very well developed molars. There are a few animals that you'd say don't, and they're usually ones that have gone down weird paths, like numbats. We’re in Western Australia. Numbats have these stumpy little degenerate teeth because basically they're sucking back on ants and termites. They don't need teeth to process food, so they don't have any purpose for them anymore. I've been trapped with a numbat once in the forestry shed. Harry Butler actually did this for me once, one of the nicest things he ever did for me. I wanted to see a numbat up close and he said, “go into that forestry shed”. This was down at Driandra and next thing I know, the door slides open and in comes this numbat. It was beautiful. It was hopping around. It landed on my shoulder, my head. I was taking photographs and I thought ‘National Geographic, here I come!’. I got back to Perth and found out I hadn't put any film in the camera.

But the answer to your question simply is that the carnivorous teeth are shaped differently than a herbivorous animal. Those of us who are paleontologists can immediately, in 99.9% of the cases, identify what an animal eats from the nature of its teeth. So no, it's just differently shaped. If there is a generality to make, most of the carnivores tend to cut their food in a vertical way, and most of the herbivores tend to cut their food more in a horizontal way and the teeth are accordingly shaped that way to make that work.

All of them are using blades one way or another, and they have to keep those blades sharp. That's the key bit, including us.

Audience Member: Thanks, Mike. I suppose this is probably potentially more of a question for Kate or for John. You were saying about the sort of primitive aspect of thegosis potentially in the brains of vertebrates. What about things like, for example, placoderms? Have you ever seen on any placoderm surface, for example?

MA: I'd love to. I mean, things like dunkleosteus and some of those guys. Clearly they are using parts of the bone of their lower jaw to function as teeth. If that isn't thegotic, I'll eat my hat. I'd love to have a look at that. I've talked to Larissa about doing some kinds of experiments that we could do with some of the animals trapped in, for example, the La Brea Tar Pits where they really must have been pissed off and not able to eat food at all. I would love to see that as a potential way of showing that the amount of tooth grinding will be proportional to stress, not eating any rate.

There's so many things to think about. I'm trying to get a group of colleagues together from the University of New South Wales to experimentally work with kangaroos to prove that this is what's happening. The reason I'm keen to do this is one of my former colleagues, Mike Beale. He was a physiologist, and he was always studying the relationship between salivary proteins and chemistry of the blood. Periodically, it was ethically done, but he would anesthetize a large kangaroo and run it to the laboratory. We would sample saliva, a bit of blood, and then he'd run it back up into the area where the animals were living. As he trundled one of these large kangaroos on a trolley past my room, I heard “crunch crunch crunch”. I thought ‘what?’. I stopped him and said, did the kangaroos do that? He said that every time he put them under anesthesia, he was using ketamine I think, and as it comes up out of the ketamine in the stage to recovery, they always grind their teeth. No food. They just immediately start to thegose. They've just had an experience of having been captured, anesthetized, and their tension levels are really right up. As they're coming out of this, they’re starting to grind their teeth.

I've said to this group, who's getting interested in this, if we can demonstrate exactly what's happening, how the muscles are being used, when and how it relates to tooth-tooth contact, nothing to do with eating, we might be able to get dentists to take a better interest in the reality of this. We have even some of our own colleagues that have published a paper, which we're busy rebutting at the moment, to say they don't even think thegosis occurs, which kind of blew me away when I read that. They hadn't read the papers. They only read one paper. It's complicated.

I think if we don't actually start doing experimental work, we're probably not going to break through this mental blockage that's in the dentistry profession anyway, although I think we've even got it in our own profession in paleontology. I don't hear talks about people analyzing how the blade systems are working. I do see a lot of very good stuff that's coming out of what Alistair's doing in Monash Uni, understanding how canines, other teeth, pierce things and what's the optimal shape for a piercing canine and so on. Great stuff. But I think we need to focus on blades too, to understand how they work and we haven't got a whole lot of research going on in that area.

Audience Member: I've always wondered in primates like baboons and mandrils and things, how much of thegosis that's employed with those canines is just a threat display? And how often does it actually escalate into bites?

MA: The footage that I've seen is that its usually not bites. I mean, most of the footage you see is usually lions and baboons sort of threatening each other, and it's bluff. A large part of what you see with the baboon doing this doesn't involve it actually, thegosing at the time that its confronting it. It's just got its mouth open and it's snarling and so on. I don't know the answer to that.

Audience Member: Are those teeth sharp?

MA: yes, they are razor sharp. It's a most interesting experience to run your finger down the back of a baboon’s upper canine, and you realize that half of the tooth is missing because its been thegosed away, leaving this fine edge of enamel, which is lethal. They're doing it because of this very complex, lower dentition. The tools that are sharpening that tooth. They're also using the front of their upper canine against the back of their lower canine and getting a second blade on the upper one as well. It's one of the most lethal natural weapons I've ever seen manufactured by an animal, it is scary.

I have said this to dentists. I've asked those who know enough about the lower two pre molars that we have. I said, “have you ever noticed any difference about the first pre molar, the front of it?”. Some of them will say, yes, that it seems to have thicker enamel and it seems to go down a little further than the other one. It's the inheritance. It's the caterine inheritance that we've got from a time when humans, our ancestors, had longer canines using the same mechanism to sharpen them.

Now we've got a shorter face, neotony. Whatever the ultimate explanation, big canines are not going to work in a face like us. So we've got shorter canines now. We've got this horizontal segment of system. We sharpen our canines the way we sharpened our incisors. Long answer to a simple question. Sorry.

Audience Member: Do you think in hominids, the reduction of canines and the change in bite corresponds with the advance in tool use?

MA: It's a disconnect. As far as we can tell, the disconnect about the oldest stone tools are about 3 million years. They were two with homo habilis, but now I think they've gone down to three. They are discovering an awful lot of other primates were making stone tools, so you'd have to be careful what you were looking at. I think the current argument, the most recent paper, said that the oldest demonstrable tool is a stone with a couple of flakes on it. It's a little over 3 million years old, but we've had shorter canines long before that. It’s impossible to defend ourselves with stone tools for cutting.

Audience Member: I'm thinking of other tools that would have been used for threat display like a stick or chucking a rock, or something.

MA: Of course, with wooden things we're never going to know. But there is that old cartoon holding up a club and saying, “do you know why I need one of these? And that's because I don't have any effective teeth or whatever”. I'm trying to argue from the moment we had shorter canines, when we had longer canines, it was effective. When we had shorter canines it's still a highly effective biting mechanism. I don't think there was ever a real disconnect. I think the weapons simply came in later. Why? I don't know. Probably they came in multiple times. It's a hugely controversial area.

Audience Member: Have you found a dentist who does get it? If so, has it made any difference to their treatment of your teeth, your oral health?

MA: Jenny, It's worth it to drive to Sydney and I'll give you a name. This guy knows what he's doing. The only thing you have to suffer is, he’ll give you a lecture about it while you're in the chair! I went with him in Sydney, because we're wound up about this and this group is growing. You can go out on Wikipedia now and there is the beginning of an entry on thegotics to try to start to get it common knowledge. We had a special meeting with all his dentist friends, and they're all so stuffy and they've all got yachts and they all play croquet and everything else. We're kind of breaking into their private time. But we gave a quick presentation with a few baboon skulls and other things to show them and bring in some familiarity here. They treated this as kind of curious, you know, they’re not letting it impact on the way that they approach their profession. They're still defending doing what they've always done. So there just aren't that many.

I know that there's at least two in Sydney and I know there's one in Adelaide who's just published a paper who seems to be coming aboard, but it's very slow. I take back my suggestion that you should ask your dentist whether they know about thegosis. It's a bit like asking a doctor while they're doing some surgery and you come up with some clever bit of anatomy, you'll cause the guy to freeze his hands while he's working on you. Best to let them get on with what they're doing.

AM: I have a dentist appointment on Tuesday. I was just wondering if there is a particular facial expression I should use when I enter the reception. Would you please put your hands together for a wonderful presentation? Thank you, Mike. It's been a privilege to have you here. Thank you, Kenny, for putting Mike on to us to get him here tonight.

Please have a safe journey home. To get out of the museum, go the same way that you came in. The door should be open. But if it's not opening for you, there's a green button on the wall. Just push that and that will let you out. There are a couple of other events happening at the museum at the moment. If somebody asks you to show a ticket, they probably wanting to see a ticket to get into some other event, not necessarily this one. Just say you've been to Meet the Museum, that would be wonderful. So thank you very much. Have a great evening the rest of your evening and drive safely.

More Episodes

A compelling discussion shedding light on the distinctive narratives of those openly embracing their HIV-positive status and what this has meant historically and in today's world.

Meet Professor Kliti Grice, the West Australian Scientist of the Year 2022, as she embarks on a quest to decipher the Earth's past mysteries.

Join a panel of featured young LGBTQIA+ writers and storytellers as they delve into the fantastical realms and real-world struggles of the exciting new anthology, An Unexpected Party.

Explore Australia's dinosaur legacy with Dr Stephen Poropat as we better understand the science behind the scenes of Australian palaeontology!

As we inevitably move towards cleaner, more sustainable forms of energy, how will a shift away from traditional mining practices transform this economy? A panel of experts explore the implications of this shift with a specific focus on how we see ourselves in a world that increasingly demands environmental responsibility.

Join Megan Krakouer, a prominent Aboriginal leader, as she discusses the nuances of her surprising change of heart on the Voice to Parliament — just a week before the referendum.

Join host Michael Mills in a captivating live recording of the Palaeo Jam podcast during National Science Week!

As AI rapidly evolves, join our panel of experts in an exploration of these complex issues, including how we can harness its power while ensuring responsible and ethical use before we're outrun by its speed.

Decoding the language of our written and oral histories in Australia.

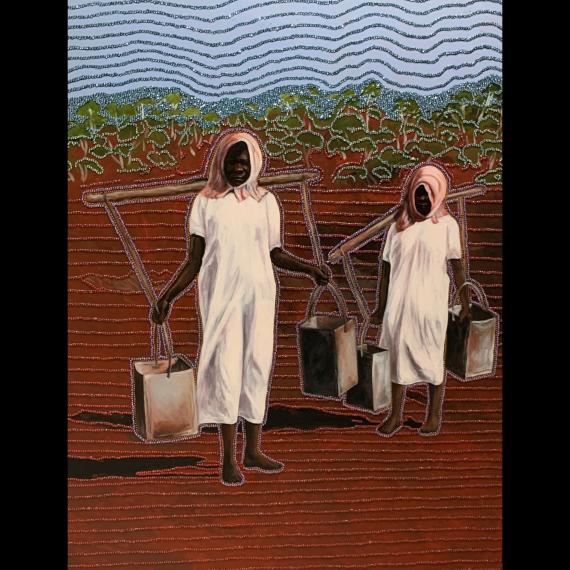

Join us for an insightful talk with the esteemed Professor Henry Skerritt, as he takes us on a journey exploring the captivating art of Jdewat/Ballandong artist Meeyakba Shane Pickett.

No, it’s not a card game but a community initiative helping us further our knowledge of a group of endemic land snails Bothriembryon affectionately called ‘Boths’.

Delve into the way Aboriginal industry professionals are shifting representations, decolonising the media space and creating visibility for Aboriginal people in the industry.

Exploring the debate surrounding the establishment of an independent, representative advisory body for First Nations people.

Aristeidis Voulgaris sharesstories from his eclipse chasing travels and discover the complex instruments and tools used in solar astronomy.

Join a panel of experts and community as they investigate the nature of queer bodies, and queer sexuality, in public space.

Join historian Toner Stevenson and astronomer Melissa Hulbert, as they share their tips on how to salute the sun during this eclipse!

Simon Miraudo and Tristan Fidler from RTRFM’s ‘Movie Squad’ are joined by Chelsey O'Brien, Curator at ACMI, as they review and discuss Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland as a foundation for contemporary storytelling in film.

In this one-off Perth Design Week talk, the Museum celebrates the remarkable women in architecture and film in a panel discussion, recorded as a part of its recent award-winning film screening.

Join world expert Dr Chris Mah from the Smithsonian Institution as he recounts his encounters with some of the most unusual creatures on the planet.